Medical Tourism Digital Promotion: A Contrastive Study From an Intercultural Communication Perspective

Abstract

The 2019 COVID-19 coronavirus disease, which has a significant influence on the medical tourism sector, necessitates the sector to focus on its online promotional messaging strategy. Given that the medical tourism sector is a global one, cultural diversity is also essential. However, promotional texts overlooked the cultural variabilities that can prevent potential global medical tourists from understanding the targeted marketing messaging. This study's objective was to look into the way in which selected Malaysian and Singaporean private hospital websites are presented to disseminate marketing messages to global patients travelling for medical treatment. For linguistic analysis, this study used Halliday's metafunction theory from the Systemic Functional Linguistic approach. The linguistic data were further analysed utilising the high and low context classification of cultures provided by Hall's cultural dimension of context dependency. High-context exhibits indirect communication and low-context demonstrates direct communication. The selected Malaysian and Singaporean webpages had features that were more common in low-context societies, such as complex code system, explicit message, highly structured message, focalisation of information and linear organisation. These findings were not consistent with the existing intercultural communication consulted in the literature which has associated Asian countries to high-context culture. The findings can assist stakeholders in medical tourism, website designers, and copywriters to understand the communicative strategies and possible cultural sensitivities in designing medical tourism websites for a country's successful international promotion.

Keywords: High And Low Context Dimension, Intercultural Communication, Medical Tourism, Promotional Discourse Analysis, Systemic Functional Linguistic (SFL)

Introduction

One of the constantly expanding services in the tourism sector is medical tourism. Ranked as the third most lucrative industry in terms of revenue creation (Xu et al., 2023), this industry has attracted the interest of many nations as they have recognised the potential of the global medical tourism market. According to Sharma et al. (2020), the size of the worldwide medical tourism market was predicted to reach USD 44.8 billion in 2019. This growth was attributed to a number of causes including economic effectiveness, cutting-edge technology, and higher-quality medical care offered by hospitals.

However, the Covid-19 epidemic is anticipated to have a significant negative impact on the worldwide medical tourism sector in 2020. In fact, many well-known medical tourism sites, including those in Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, which are among Southeast Asia's most well-liked destinations, have suffered significantly from COVID-19 (Gopalan et al., 2021). These nations have appropriate electrical equipment and facilities that meet international medical, health, and wellness standards, which helps the medical tourism business flourish there (Xu et al., 2023). Furthermore, as one of the first nations to be seriously impacted by the virus, China has also made many Southeast Asian nations that depend on it for their labour markets, supply networks, and tourism industries in the region more exposed to economic risks (Oxford Analytica, 2020).

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Malaysia was ranked among the top Asian nations for medical tourism together with Singapore and Thailand (The Star, 2023). In Penang, Malaysia, 500 000 Indonesians travel annually for medical treatment, according to a poll, and this figure is anticipated to rise (Fathia, 2018). However, according to The Star (2023), Malaysian healthcare travel revenue observed a significant decline in healthcare travel income in 2019 from RM1.7 billion to RM777 million and RM585 million in 2020 and 2021, respectively, as a result of Covid-19's adverse effects on the countries' profitability, particularly from private facilities. With regards to this, many nations have adopted strong strategies to combat the reduction in revenue from the medical tourism business in an effort to stem the revenue loss they have had to face as a result of the pandemic. Hospital administrators and service providers should make the most of their service promotions, particularly on digital platforms, given that consumer internet use for accessing healthcare information and exposure to medical tourism advertising is a key driver of medical tourism (Mason, 2014). The advertising material needs to be more inventive, focusing on soft selling marketing techniques, such as brief videos that provide information and useful health advice while presenting the facilities, doctors' credentials, and special services offered.

Malaysia has included RM35 million in its 2021 Budget for the digitalisation of the healthcare travel industry (Malaysia Healthcare Travel Council, 2020), demonstrating the awareness of the country's leadership towards the importance of digital platforms to connect with medical tourists from around the world, particularly in light of the pandemic's negative effects on the industry. Meanwhile, the inclusive new budget with a recovery package that is specifically targeted at Singapore's aviation sector to stimulate travel is one of the important initiatives in Singapore to increase the revenue of the medical tourism business (The Straits Times, 2022). These activities, which are widespread in the medical tourism sector, are centred on web-based service and product advertising and promotional messaging.

However, if strong web marketing is not implemented to persuade potential medical tourists, the strategies used by Malaysia and Singapore will not be realised. High quality internet information is crucial for drawing in medical tourists, according to Loda (2011) who also stressed the importance of digital marketing. The majority of medical tourism practises are hospital-centric; as a result, the websites of private hospitals that encourage medical tourism are therefore among the online advertising channels that need to be taken into consideration. Websites are used for online promotion, which includes text as well as collections of photos, multimodal content, interactive elements, animated visuals, and audio (Wurtz, 2005). Because of this intricacy, it is clear that it is difficult to design and build engaging and inventive web pages.

Due to the cultural sensitivity of their design and content, websites are created and presented in a variety of cultural contexts, which further complicates the process (Stoian, 2015). Culture-specific differences in communication styles are likely to make it challenging for websites to effectively communicate their messages. This is so because websites are sensitive to cultural differences and have different characteristics depending on where they are utilised (Cermak, 2020). Numerous research have concentrated on understanding and studying variations in website design due to intercultural communication as the outcome of the influence of online and global marketing, taking into account the challenging issues of worldwide marketing of digital medical tourism with varied cultures. According to certain studies, communication methods on websites matter. The design of websites or how different cultures interact with them have been extensively studied in the literature on culture and websites (Cermak, 2020) as have the ways in which different cultures communicate on websites (Oswal & Palmer, 2018). Some research (Sari & Putra, 2019; Usunier & Roulin, 2010) have looked into to what extent and how website content and design mirror the interaction preferences of those who create high-context cultures as opposed to low-context cultures. Although cultural relevance has been taken into account in the promotional strategy of such websites, there have been very few studies that have primarily focused on the marketing of medical tourism.

In conclusion, the goal of this study is to examine, from the perspective of intercultural communication, how a private Malaysian hospital website employs images and words in medical tourism marketing to potential foreign patients. In more detail, this study has two goals. It looks at two things: how a private hospital's website uses words and images to promote medical travel, and whether or not the findings can be justified from the standpoint of cultural differences. It is intended that the study's conclusions and learnings would help the stakeholders create and implement a more effective marketing strategy for promoting medical travel on websites.

Literature Review

Culture and discourse

According to Hall (2000), the creation and exchange of meanings within a community or group of people is the primary focus of culture as a set of practices. People don't engage in communication as if they are starting from scratch; instead, they contribute their own experiences, feelings, and communicative skills to any job in addition to the knowledge, comprehension, and presumptions that are common across sociocultural groups that involves communication (Van Dijk, 2009). Language is crucial to any culture since it is the primary medium of communication. According to Mithun (2004), it is a potent tool for establishing, preserving, and honouring culture and interpersonal bonds. Accordingly, it would appear that the systems of language, situation, and culture are essentially linked (House, 2007; Matsumoto & Juang, 2007). Language is regarded as a resource, a rich array of meaning-making possibilities that can be justified by social contexts and cultural norms. According to Coupland (2011), these in turn should be viewed as resources for creating meaning.

Culture has an impact on discourse and is also influenced by discourse (Şerbănescu, 2007). Like all discourse, the discourse on medical tourism is a product of and a representation of culture. It is thought to have strong cultural overtones and can be viewed as a reflection of social reality (Hiippala, 2007; Mocini, 2009). Producers, copywriters, and promoters frequently choose the truth that they accurately portray and convey the principles and goals that are closest to their own hearts (Dyer, 2008). Therefore, the cultural milieu and its value systems determine what is said in tourist materials (Hiippala, 2007). The promotional writings are written with an audience in mind in addition to portraying the culture of their producers. Depending on local speaking patterns, listening preferences, and audience expectations, marketing for a location or asset may vary from country to country (Lewis, 2004). The original wording might therefore be modified to reflect the cultural norms and values of the target audience.

The discipline of cultural research has taken notice of the discourse that promotes medical tourism. Communication that ignores cultural variabilities can possibly signal problems (Lailawati, 2005) because culture has always been an essential domain for global business study (Kabasakal et al., 2006). Additionally, culture has an impact on discourse as well (Şerbănescu, 2007). Online promotional websites have recently paid attention to studies on the cultural contexts of promotional discourse. The significance of cultural context in internet promotion has been the subject of some studies (Frederick & Gan, 2015; Karacay-Aydin et al., 2009; Wu, 2018). Wu (2018) looked into the methods used by various tourist places with various cultural backgrounds to sell their local attractions online to audiences around the world. Karacay-Aydin et al. (2009) studied the level of culturally-based web communication variations and found significant variation in how cultural values are portrayed on the websites they analysed. Results from Frederick and Gan's (2015) investigation on how the stakeholders of medical tourism distinguish themselves from one another on their websites are in agreement with those from Karacay-Aydin et al. (2009) findings. The researchers discovered that there were geographical variations brought on by cultural elements. These previous studies demonstrate that a lot of research has been devoted to elucidating and comprehending the ways that the effect of internet and international marketing affects the distinctions in communication between cultures in designing websites. The research, however, weren't centred on how promotional messages were delivered in a discourse. Therefore, it is important to study this kind of promotional language from a functional perspective utilising SFL in order to understand the intended meaning.

Moreover, since it is argued that medical tourism is a cross-cultural phenomenon and to promote medical tourism across cultures, the cultural diversity among different communities should be dealt with in a careful and proper way. The nature of the global intercultural advertising, the copywriter of any tourism promotional materials has to keep in mind the cultural context, the needs, and expectations of the audience to ensure a maximum impact in culturally different situations (Woodward-Smith et al., 2021). As a result, this study intends to make a contribution to the area of promoting digital medical tourism by offering fresh perspectives that were drawn from an analysis of the linguistics of a private hospital website and expanded it to take into account the standpoint of intercultural communication.

Intercultural communication requires contact between parties with varied national cultural traditions (Croucher et al., 2015). Meaning-based maps are present in cultures to aid in understanding the outside world. The weight of these meaning maps varies depending on the culture (Lehtonen, 2000). In this study, the communication methods employed on the websites of private hospitals in Malaysia and Singapore to attract potential overseas patients were studied. Every aspect of culture exhibits cultural peculiarities and characteristics in specific areas and facets. To better comprehend the variations in communicative behaviours that may be entrenched in a country's culture, the dimension of cultural viewpoint was further examined in this study. How words are used to describe locations, circumstances and people can assist in elucidating social communication practiced in the country and at the same time demonstrate cultural patterns (Wan Abdul Halim et al., 2022). In terms of analysis, the cultural aspect of context was chosen since it seemed to be the most pertinent to the type of message under study and its purpose (Hall, 1976, 2000; Hall & Hall, 1990). SFL was selected for the analysis of the websites in this study so that the highlighted characteristics from the linguistic analysis would be able to reflect the cultural communicative strategies adopted. As such, this study also attempted to emphasise the fact that cultural competence needs to be given an important focus in today’s global business world.

Cultural variability

Population expansion and urbanisation are two ways that social and cultural variables directly impact the growth of tourism (Qiao et al., 2023). However, the cultural diversity aspect must be taken into account, despite the enormous influence that culture plays in promoting tourism. The universal truths, with the reality that life is short, the inherent similarity of humans, whether they be psychological or physical, human activities are universal such as sleeping or eating, and their responses to external stimuli, such as laughing or becoming angry, are some examples of similarities between cultures. They are a result of the historical, the physical, social, cultural, economic, political, and other environments that have influenced the growth of particular communities, groups, or nations. Variations also rely on how different exterior stimuli are perceived by people and how these perceptions relate to diverse exterior aspects (Şerbănescu, 2007). All of this results in specific cultural patterns, which influence a way of life and perspective on the world (Şerbănescu, 2007).”

Different cultural frameworks and dimensions, such as individualism/collectivism (Hofstede, 1984), high/low context (Hall, 1976; Hall & Hall, 1990), and compassionate orientation (House et al., 2004), can capture cultural variation and its traits. People from many national cultures seem to operate within the same framework and exhibit comparable attitudes and habits. Despite the existence of exceptions, "it is still possible to make reasonably accurate statements (generalisations)" about a given culture's traits (Peterson, 2004, p. 23). A culture's classification along one or more dimensions provides a basic framework for comprehending and interpreting particular social behaviour rather than a "precise diagnostic" (Şerbănescu, 2007, p. 154). The generalisations of cultural diversity can also aid in predicting the social and personal behaviours of a culture's members. In addition, they provide a unified framework for explaining cultural differences amongst individuals (Şerbănescu, 2007).

According to Hofstede et al. (2002) and Şerbănescu (2007), cultural dimensions can be positioned across a cultural spectrum. Despite the fact that the ends of the continuum may be distinguished clearly from one another, neither end of the spectrum is thought to contain a culture. Since cultures are “dynamic, continuously developing, and evolving”, different contexts and circumstances can lead to cultural aberrations, (Neuliep, 2017, p. 45) which can be impacted by a variety of causes (Şerbănescu, 2007, p. 155). These may be contextual, situational, technological, economic, social, political, historical, religious, or related to the singularity of humans (Dumitrescu, 2009; Şerbănescu, 2007). Cultures constantly adapt to new circumstances, take in elements from all around, and change over time (Besnier, 2020). It can be said that all modern nations are “culturally hybrid” (Hall, 1976, p. 207) and “multidimensional” (Hofstede et al., 2002, p. 126) as they are “integrated and related in new spatio-temporal terms” (De Cillia et al., 1999, p. 155) as a result of globalisation, on one hand, and localisation, on the other (Bloor & Bloor, 2013, p. 140; De Cillia et al., 1999, p. 155).

However, for the purposes of this study, context (Hall, 1976, 2000; Hall & Hall, 1990) was chosen as the cultural dimension that was most pertinent to the sort of message under study and its purpose. In particular features and areas, all cultural dimensions can exhibit cultural characteristics. As their study can disclose properties of various dimensions, it might be related to the metafunctions. In the mean time, culture-specific traits can also predict communication styles (Şerbănescu, 2007).

Theoretical Framework

SFL framework

Using Halliday's metafunction theory for language analysis, this study followed the Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) method. The linguistic examination of a few websites' selected web pages served as the basis for the analysis. According to Halliday (1985-1994), the concept of metafunction is one of a select group of concepts required to explain how the semantic system of language is organized. Metafunctions are systemic groups that are part of a collection of semantic systems that provide meanings of a particular type.

Linguistic analysis

The works of Halliday served as the foundation for Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), which is a "very useful descriptive and interpretive framework for viewing language as a strategic, meaning-making resource" (Eggins, 2004, p. 2). The linguistic analysis in this study is structured in accordance with Halliday's (1985-1994) proposal of metafunctions as well as Halliday et al. (2014), who examined each function separately. Among these communicative functions is ideational (experiential and logical), that refers to how reality develops through discourse. Interpersonal communication focuses on the linguistic choices that people make to perform their many different and complex interpersonal relationships, whereas textual communication examines the communicative nature and internal organisation of a text (Halliday et al., 2014). According to the distribution of sentence types, simplexes and complexes, the texts were characterised by logical analysis. Logico-semantic and tactic linkages were examined in the clause complexes. Each clause is examined in the experiential analysis along with its participants, processes, and circumstances. The interpersonal focuses on speech roles, finites, modality, polarity, mood selections, and mood structures as well as categories of subjects, finites, and adjuncts. The types of topics and their evolution are also included in the texts.

Culture and discourse

Hall proposes two categories of culture: high-context and low-context. High-context cultures, where knowledge is situational and relational, have less need to be explicit and more often use nonverbal cues to convey message (Hall & Hall, 1990). Since meaning is assigned based on common experiences and expectations, which results in inferences and contextual predictions, some elements within this context are presented indirectly or not at all. Low-context cultures, however, operate in the exact opposite way. Low-context culture members utilise direct and clear communication rather than on nonverbal cues when constructing and interpreting meaning.

Methodology

Data collection

The information for this study was acquired from the websites of one private hospital in Malaysia and one private hospital Singapore. For this study, Prince Court Medical Centre from Malaysia and Gleaneagles Hospital from Singapore were involved. Three webpages from each hospital were selected based on a few search criteria. Firstly, the language used on the website chosen should be in English. Since the study sought to investigate the way medical tourism in different countries is promoted to the international market, thus, selecting websites that use English as the language of promotion fits the purpose. Next, the study's emphasis was on private hospitals from Southeast Asian nations, which dominate the market for medical tourism. In Southeast Asia, Malaysia and Singapore are the two leading countries for medical tourism (Gopalan et al., 2021), and for this reason, six websites from the two nations were chosen based on how effectively they serve the purpose of marketing medical tourism to potential foreign medical tourists while also providing the greatest description of the capabilities and expertise of the private hospital.

Method of analysis

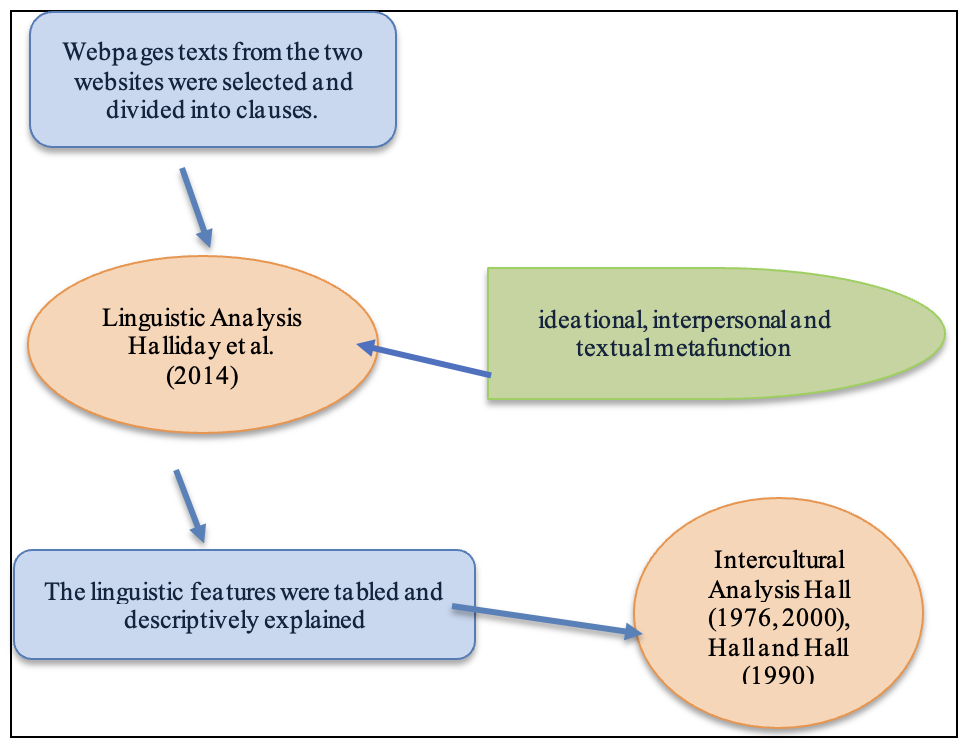

Figure 1 illustrates the process flow for data analysis.

This study's analysis is divided into two phases. The first part of the analysis is linguistic, examining how words are used on the websites to convey meaning, and the second stage is intercultural, exploring how the language is understood in different cultural contexts. A manual process that involved multiple steps was conducted to analyse the websites of the private hospitals that were chosen. The texts were first broken into clauses once the six webpages from the two websites had been chosen. Following this, the ideational and textual metafunctions of the SFL were used to identify the linguistic aspects. Third, compositional and representational metafunctions were used to assess the most prominent visuals on all of the chosen webpages. Fourthly, information pertaining to linguistic characteristics was laid down.

Findings and Discussion

Linguistic analysis

The linguistic analysis of Malaysian and Singaporean websites are presented in Table 1 which provides linguistic realisations from the SFL metafunction. Analytical tools of experiential (Transitivity) and textual metafunctions were utilised for linguistic analysis. The identified language characteristics from Malaysian and Singaporean webpages are presented pertaining to transitivity elements which consists of processes, types of participants and types of circumstances in form of percentages. The percentage was calculated from the sum of all clauses on the chosen pages.

Malaysia – Prince Court Medical Centre (PCMC)

The identified language characteristics from three Malaysian selected webpages are presented in Table 1 pertaining to transitivity elements which refers to the processes in form of percentages. The percentage was calculated from each clause's total on the chosen websites, namely About Us (M1), Medical Tourism (M2) and International Business Lounge (M3).

Ideational (Transitivity) Analysis: Relational processes are mostly used to transmit experience. For example, "Prince Court Medical Centre is a 270-bed private healthcare facility" elements of the hospital amenities and services. There are numerous examples of material processes that, in addition to relational processes, objectively describe the hospital's facilities, such as "Our International Business Lounge is geared to welcome you and help you understand”. In regards to the participants, in addition to medical tourists, the names of the hospital and medical tourism also commonly occurred in actor, aim, carrier, and attribute position in the text to offer familiar recognition, for example, "Malaysian healthcare" and "PCMC". The locative circumstances that place the attraction in time and space serve as the primary source of background information.

Table 2 presents the summary of textual analysis from M1, M2 and M3 webpages. The occurrence of theme types and their thematic progression patterns is presented in form of percentages. The percentage was calculated from the total number of separate conjoinable clause complexes on the webpages.

Textual Analysis: The PCMC texts are composed of declarative clauses. The highest number of occurrences for theme type is the unmarked topical theme at 93.75%, followed by the textual theme at 56.25%. There is very limited occurrence of marked topical theme and interpersonal theme, respectively at 6.25%. Table 3 presents the results of the theme types found in PCMC webpages along with examples of each kind from the texts. Italics are used for words or phrases that are in the theme position.

The dominant use of unmarked topical themes in PCMC texts is realised by participants as the subject. Apart from highlighting the role of Prince Court Medical Centre and its attractions, the unmarked themes also attract the readers’ attentions by directly addressing them as “foreign patients seeking medical treatment in Malaysia” to establish rapport with the readers. Although infrequent, the use of topical theme markers in PCMC texts aids website designers and copywriters in emphasising elements they deem crucial and placing them at the beginning of the clause, such as to emphasise the current development of medical tourism status, “Today, the medical care in Malaysia is on par with the best in the world where innovation and international expertise are key”. Meanwhile, textual themes for PCMC webpages relate the private hospital clause to its context which refers to the current medical tourism market e.g., “There are countless reasons why PCMC is an ideal destination for medical tourism”. In these examples, the clauses are connected and provide cohesion to the text.

Singapore – Gleneagle Hospital (GLN)

The identified language characteristics from three Singaporean selected webpages are presented in Table 4 pertaining to transitivity elements which refers to the processes in form of percentages. The percentage was calculated from the total of each clause in the selected webpages namely About Us (S1), International Patient Guide (S2) and Rooms and Facilities (S3).

Ideational (Transitivity) Analysis: The processes preferred for the presentation of the hospital are relational process to describe the range or services and specialty of Gleneagles Hospital as they “provide advice on the estimated cost of treatments and procedures” and “offers a selection of in-patient rooms to meet your personal needs and comfort”. Meanwhile, material processes are used to present credibility of the hospital to convince the prospective medical tourists, e.g. “Gleneagles Hospital has been accredited by the Joint Commission International (JCI)”. As for the participants, the hospital and its attractions, and the medical tourists appeared most frequently in the role of actor, identified and identifier, e.g. “At Gleneagles Hospital, our team of healthcare professionals will provide the support and care you need”. The establishment of the hospital is represented and portrayed by their professional medical staff to capture the interest and confidence among international medical tourists. The background information situates the actions mainly in place and purpose.

The summary of textual analysis from S1, S2 and S3 webpages are gathered and presented in Table 5. In the form of percentages, it displays the frequency of various themes and thematic progressions on each chosen GLN homepage. From the total number of independent conjoinable clause complexes, a percentage was derived to show how frequently each element appeared, its theme status, and how it progressed thematically.

: The study showed that declarative and imperative clauses were the main types of content found in GLN webpages. Unmarked topical themes are more prevalent than marked topical themes on the Gleneagles Hospital website, accounting for 84.6% of all occurrences, followed by 23%. Next, the textual motif comes in at 15.4%, followed by the interpersonal theme at 7.69%. In Table 6, which also includes samples from the texts, the theme types' results for S2 webpages are displayed. The topic position is indicated by italicising the word or phrase.

The texts present the hospital Gleneagles Hospital mainly by unmarked themes. Unmarkedness results in an unambiguous, whole statement that leaves no opportunity for interpretation (Giora, 1991). The majority of participants are in topic positions, with information being the main focus. However, there are a few intances of process at the theme position in imperative clauses such as “Learn more about the Vaccinated Travel Lane (VTL) Air”. The finite “learn” is the first element in the clause, which suggests or requests the prospective international medical tourists read or explore more on the latest facility - Vaccinated Travel Lane (VTL) Air – provided by them since they allow certain travelers to seek medical treatment in Singapore quarantine-free. The only case of interpersonal theme in S2 texts such as “please read our FAQ” aims at presenting persuasive element of GLN copywriter to appeal the readers to read and learn more about the general enquiries on COVID-19 for S2 international patients. In the meantime, textual themes in GLN webpages are realised through structural conjunction “when” and conjunctive, “thus” to connect the private hospital's amenities as well as their accreditation rewarded to promote international medical tourism for the purpose of receiving medical care.

Cultural analysis

Table 7 presents the cultural elements and patterns determined from the language advertising message and approach for the Malaysian and Singaporean websites. Hall's (2000) cultural component of context dependency served as the foundation for the cultural analysis. As defined by Hall and Hall (1990), the background knowledge of an occurrence is referred to as context and is intrinsically linked to its meaning. This means that the way discourse is organised overall, the reality that is given, and the relationship between its creators and receptors can all reveal an affinity for a particular communicative context. The promotional messages and communicative strategies that have been indicated through the identified language features in the Malaysian and Singaporean websites can be interpreted and compared from the cultural perspective of context.

Contrastive analysis of cultural characteristics of Malaysian and Singaporean websites

Table 7 demonstrates that Malaysian and Singaporean private hospital websites share several similarities. The cultural analysis reveals that these websites are comparable in terms of how their webpages are organised and structured, the linguistic messages they convey, including their transitivity and textual components, and how their visual messages are presented and put together. The informative aim of the message of the webpages from Malaysia and Singapore is predominant as by using both text and images, it describes the attraction and gives some information on the facility. They identify the hospital facilities and expertise, describe it and give some background information. Most of the time, in a presentation that is educational, impartial, and impersonal, persuasion is hidden. Information is therefore primarily broad. This general function belongs to low-context culture as through the use of titles and visuals, it serves to grab readers' attention and keeps them reading by highlighting the private hospital's amenities.

The transitivity system in all selected webpages are varied; material, relational, verbal, mental and existential processes interplay to create a complex text with elaborated message which is typical in low-context culture. The recommended type of process is material process which mostly refer to the actions through services and expertise offered by the private hospitals. Relational identifying processes are also frequent, which establishes the purpose of the text to identify and describe the private hospitals’ attractions, making the texts to be more descriptive and informative. These promotional strategies demonstrate highly structured message and elaborated code system which belongs to low-context culture. Additionally, attributional processes occur frequently in describing the private hospital. The most frequent type is intensive and possessive processes, with a lot of attention paid to circumstantial relations. These high circumstances element as background information reveals the presence of elaborated and high structured message found in low-context culture. The location, circumstances, facts, and attractions' spatial and temporal locations serve as the key sources of background information.

More frequently said than implied, the participants in the three sets of webpages, indicating direct and explicit message as in low-context culture. The favoured one is the private hospitals, even if the topic is the disease or medical tourism and its attractions. Its placement inside the subject and the fact that identification is more crucial than presentation underscore its centrality. The private hospitals developed, visited, and was described as the entity in a non-linear organisation as in high-context culture. The private hospital management figures are almost absent in all webpages, creating an impersonal, impartial message indicative of a national and worldwide publicist. It continues to sound impersonal with the fact that it is mentioned by its holdings in the few instances it occurs. There is no emphasis of feelings in this element as it suits the low-context culture. These webpages present factual, timeless, and objective information which reflects organisation that is preferred by low-context cultures as seen by the prevalence of the declarative mood, the preference for the present tense, and the predominance of unmarked themes. The message was developed by mainly reiteration themes indicating a constant attention to the private hospital’s marketing and benefits, organisation that is preferred by low-context cultures (Şerbănescu, 2007).

Along with these cultural connections, certain distinctions were also found across the three countries' chosen websites. They appear to differ in terms of information transmission and preferred modality, language message structure and logical and representational purposes, and interactive characteristics of the visuals. In the case of the Malaysian webpages, the text is mainly of medium length, syntactically elaborated and dominated by clause simplexes. The Malaysian hospital’s website used short and transparent page to present their private hospitals and to make information easy to access, indicating a clear and concise message which is a characteristic found in low-context cultures (Hall, 1976).

The private hospitals and their attracting qualities are recognised and explained mostly using material process followed by relational process which indicate a highly structured message as in low-context culture. Interestingly, there is very limited interpersonal theme employed in the selected Malaysia webpages as they appeared impersonal and lack the emphasis on feelings, which is typical in low-context culture. In addition, Malaysian texts are also dominated by unmarked and a few marked themes that promote objectivity and focalisation of information and organisations which are favoured in low-context culture. The low new theme in Malaysian webpages proves that the flow of message and the promotional message are equally important. Very low new theme also indicates clear thematic progression that promote interconnectedness of ideas as preferred in low-context culture.

Overall, the Malaysian webpages are more enlightening, direct, provocative, clear, impartial, and useful. Regarding elaboration, complexity, and structure, their language statements are broad, consistent, logical, and unambiguous. The website's unique sections devoted to the promotion of medical tourism show how well-organized and focused their content is. These traits appear typical of low-context civilizations because they rely on a complex code system and communicate a distinct, explicit, focused, and explicit message (Şerbănescu, 2007). The message in Malaysian websites is divided clearly between promoting private hospitals and promoting medical tourism in the country where the potential medical tourists are convinced that Malaysia aspires to be the best healthcare nation in Asia and to deliver all-encompassing care at the highest standards by utilising top-notch facilities, cutting-edge technology, and superior customer service for all medical tourists. This promotional strategy that includes a balanced verbal and visual modes in the webpages reflects both low-context and high-context.

Meanwhile, in the Singaporean webpages, the text was rather short and constructed with mainly simple clauses, transmitting a direct and explicit message which characterises low-context cultures (Şerbănescu, 2007). Unlike Malaysia, the low modalisation in Singaporean texts indicate reduced ambiguity in the interpretation of information given as fact, transmitting a direct and explicit message as preferred in low-context culture. The prospective medical tourist is also addressed in the Singaporean texts. They are included in a group of patients when broad phrases are used, or they are addressed personally and individually when personal pronouns or imperatives are included. When expressed, the roles of senser—the one who looks around and learns—and actor—the one who travels—are potential medical tourists. This promotional strategy reflects a direct and explicit message as preferred in low-context culture. The use of interpersonal themes in Singaporean texts promote subjectivity with the inclusion of the writer’s personal opinion that reflects an emphasis on feelings as preferred in high-context culture. Additionally, the presence of new themes may disrupt the message, which is typical of high-context cultures (Şerbănescu, 2007).

In conclusion, every nation promotes medical tourism in a unique way to potential foreign patients. It is clear that they work to build a reputation for the private hospitals that are advertised, which eventually spreads throughout the nation. Up to a certain point, the specified uniqueness is comparable. It is frequently indirect, objective, and connotative. Malaysian and Singaporean websites feature clear, all-encompassing, and brief statements from a contextual standpoint, which is a typical organisation in low-context communication. These websites were chosen from the three countries.

Interpretations of cultural findings

Table 8 demonstrates that the chosen webpages contain elements of both low and high context culture, but they lean in different directions. The Malaysian webpages are mainly characterised by low-context cultures with all cultural context features such as direct and explicit message, elaborated code system, focalisation of information, linear organisation and highly structured messages. In addition, since Malaysian websites are also constructed around unelaborated messages that place a strong emphasis on sentiments, they also have minimal contextual characteristics that are characteristic of high-context cultures. Meanwhile, the Singaporean webpages combine features of both types of cultures with almost an equal number of low-context culture and high-context culture. The presence of the high-context cultures is primarily visual in Singaporean websites. Usunier and Roulin (2010) asserted that high-context communication style can be unfavourable to the suitable design of websites, causing them to become vague, dull, and less communicative. Table 8 presents a summary of the contextual features which presents the frequency of cultural context discovered in Malaysian and Singaporean private hospital websites.

The significance of culture in the various marketing techniques employed by the website copywriters has shown that the intercultural communication literature that has been consulted do not align with the two countries. It serves as proof that cultures are alive, evolving and constantly changing (Neuliep, 2017). This is demonstrated by the Malaysian and Singaporean websites' departure from the established cultural categorisation and potential influence of several causes.

The departures from customary cultural patterns that have been noted, as was previously mentioned (Neuliep, 2017), may be a sign of cultural change. The globalisation's influence on culture, the internationalisation of English, and the domestic reconfiguration of Malaysia and Singapore's economies, politics, and societies can all be used to explain these inequalities. According to Xu et al. (2023), cultures may be shared between countries in the tourism industry, opening up new avenues for communication on a worldwide scale. They also demonstrate how well people can understand one another's cultures.

In addition, the Internet's tendency to be a communication tool and the promotion of medical tourism as a communication environment have both influenced cultural developments. The emergence of internet advertising as a whole new mode of communication is one of the numerous recent developments when utilising technology for message transmission. According to Wurtz (2005), the internet is a low-context communication medium, but Cook (2008) views promotion as a high-context environment.

For Malaysian communication styles, it might be argued that global English language usage and mobilisation may have an impact on Malaysian culture. This result is consistent with Lailawati's (2005) study, which looked at context communication in Malaysian Malay style. Her research discovered a tendency in Malay communication that has changed from being high-context to being more low-context, and she concluded that this change is due to mobilising on a global scale when individuals travel and embrace new perspectives and behaving and assimilate them into their value system. However, Lailawati's research has solely looked at the Malays. This study, which examines how the nation's businesses are promoted online to foreign markets, includes not just the Malay people but also other dominant races that retain their own cultural traditions, such as Chinese and Indian. With regard to that, the cultural deviation finding of Malaysian communication of the study can be associated with the existence of “new culture” due to the blending and mixing of the three civilizations. This is in line with Wan Abdul Halim et al. (2021) study that claimed worldwide mobilisation, English's extensive use, and changes in communication and culture brought on by the growth of Malaysia's multiracial communities could all have an impact on Malaysian culture.

Meanwhile, although predominantly displaying traits of a high-context society, notably in its visual communication due to the copywriters' inclination, some low-context communication patterns were also discovered in the linguistic mode of Singaporean communication. Due to the significant changes, it has undergone in its politics, economics, and society, as well as external causes like globalisation, Singapore has long been acknowledged as one of Asia's developed nations. Their website's communication context, media methods, and detected elements all appear to be related to variances from the expected cultural context features. The ethnic diversity of Singapore's people is matched by its linguistic diversity, according to the history of language regulation and development in the city-state. Dialect speech groups are present in all three of the major ethnic communities.

The authorities of Singapore determined that there would be four official languages in the new country as a compromise between the three main ethnic populations at the time of independence. Given its worldwide prominence and Singapore's colonial past, Malay, Chinese (Mandarin), and Tamil were chosen to reflect the three ethnic-cultural traditions of the country, in addition to English because of its international status and Singapore’s colonial background. In accordance with the island-state's history and geographical location, Malay was chosen as its official language out of the other four. The national language's function now, however, is more ceremonial than functional, claimed Kuo and Chen (2022). In Singapore, English is the de facto official working language. As a result, we can draw the conclusion that Singapore is a developed nation that is more direct, open, and sophisticated, and that the results of this study's cultural analysis support this conclusion. As a result, it is not surprising that their communication in marketing medical tourism to the outside world places greater emphasis on visual use than on text-based information descriptions.

Conclusion

In the global economy's current competitive environment, the target market for any company, especially those in industries like medical tourism must target the international markets apart from local markets. Because of this, some researchers in commercial situations such as Louhiala-Salminen and Kankaanranta (2011) draw attention to the important place that "global communicative competence" plays in marketing tactics and strategies. This study compared the websites of private hospitals in Malaysia and Singapore, two of the top destinations for medical tourists in Southeast Asia, to deal with this cross-cultural communication ability. The goal was to determine whether any distinctive cultural characteristics could be detected in the expression of linguistic features.

The framework developed by Halliday et al. (2014) as well as the intercultural analysis framework developed by Hall (1976, 2000) with Hall and Hall (1990) have effectively shown that the dimension is appropriate for examining discourse that promotes tourism online. The study's usage of a two-phase framework demonstrates that there are other methods for analysing SFL besides discourse analysis frameworks to identify promotional messages. In order to observe the emerging communication styles from a cultural standpoint, particularly from Hall's cultural context dimensions, it can also be integrated with intercultural analysis. The method should be carefully chosen to meet the study's context and objectives. The selected Malaysian and Singaporean webpages contained aspects that were more common in low-context societies through the use of elaborated code system, explicit message, focalisation of information, highly structured message and linear organisation. These findings were not consistent with the existing intercultural communication consulted in the literature which has associated Asian countries to high-context culture. It is recommended that given the results of this investigation, a suitable framework and analytical strategy be carefully chosen in order to complement the study's context and objectives.

Numerous different meanings could be concealed in language and imagery, as shown by the linguistic analysis and cultural interpretation used in this study. These underline the complexity of communication, where small adjustments to one or more elements can result in a completely new message. Communication is about making decisions; the final message is composed of all the decisions made, but only one bad decision can change the entire message. The proper decisions must be made at the extra-linguistic and cultural levels in order for the communication choices to be successful (Elena, 2014). A website's success depends critically on how language, image, and their combination convey meaning in cross-cultural contexts. The objective of this study was to give a thorough perspective of the intricacy of digital promotion of medical tourism. A special focus on this form of communication is necessary in light of the diversity of discourse and culture as well as the rising trend of online medical tourism.

The creation of effective and appealing websites is not an easy undertaking, and website stakeholders, promoters, and copywriters must recognise this. They must pay greater attention to the communication used by websites promoting medical tourism, which include the creation of meaning through the website's language and images as well as any potential cultural interpretation. For the purpose of collaborating on online tourism promotion, a very diversified team composed of experts in the fields of marketing, computer communication, and graphics is required.

References

Besnier, C. (2020, December). History to myths: Social network analysis for comparison of stories over time. In Proceedings of the The 4th Joint SIGHUM Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Cultural Heritage, Social Sciences, Humanities and Literature (pp. 1-9).

Bloor, M., & Bloor, T. (2013). The Practice of Critical Discourse Analysis: an Introduction.

Cermak, R. (2020). Culturally Sensitive Website Elements and Features: A Cross-National Comparison of Websites from Selected Countries. Acta Informatica Pragensia, 9(2), 132-153.

Cook, G. (2008). 5. Advertisements and Public Relations. Handbook of Communication in the Public Sphere.

Coupland, N. (2011). The Sociolinguistics of Style. In R. Mesthrie (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Sociolinguistics. Cambridge.

Croucher, S. M., Sommier, M., & Rahmani, D. (2015). Intercultural communication: Where we've been, where we're going, issues we face. Communication Research and Practice, 1(1), 71-87.

De Cillia, R., Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (1999). The Discursive Construction of National Identities. Discourse & Society, 10(2), 149-173.

Dumitrescu, M. (2009). A Course in Intercultural Business Communication. The Academy of Economic Studies. Bucharest.

Dyer, G. (2008). Advertising as Communication.

Eggins, S. (2004). Introduction to systemic functional linguistics. A&c Black. https://repository.dinus.ac.id/docs/ajar/An_Introduction_to_SFL_2nd_edition_Suzanne_Eggins.pdf

Elena, C. R. (2014). Intercultural Dimensions in Language Teaching–The Function of Pedagogical Translation. Anuarul Institutului de Cercetări Socio-Umane „CS Nicolăescu-Plopșor”, (XV), 201-211. https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=ro&user=Pt0TDWwAAAAJ&citation_for_view=Pt0TDWwAAAAJ:9yKSN-GCB0IC

Fathia, L. (2018). Tidak hanya Aceh, banyak orang indonesia memilih berobat ke Penang. berikut alasannya [Not Only Aceh, Many Indonesians Choose Treatment at Penang. Here are the reasons]. https://liza-fathia.com/warga-indonesia

Frederick, J. R., & Gan, L. L. (2015). East-West differences among medical tourism facilitators' websites. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(2), 98-109.

Giora, R. (1991). On the cognitive aspects of the joke. Journal of Pragmatics, 16(5), 465-485.

Gopalan, N., Mohamed Noor, S. N., & Salim Mohamed, M. (2021). The Pro-Medical Tourism Stance of Malaysia and How it Affects Stem Cell Tourism Industry. SAGE Open, 11(2), 215824402110168. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211016837

Hall, E. (1976). Beyond Culture. Doubleday.

Hall, E. (2000). Context and Meaning. In L. Samovar and R. Porter (Eds.), Intercultural Communication: A Reader (9th Ed., pp. 34-43). Wadsworth Publishing Co.

Hall, E., & Hall, M. (1990). Understanding Cultural Differences. Intercultural Press Inc.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1985-1994). An introduction to functional grammar. Hodder Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., Matthiessen, C. M. I. M., Halliday, M., & Matthiessen, C. (2014). An Introduction to Functional Grammar.

Hiippala, T. (2007). Helsinki: A Multisemiotic Analysis of Tourist Brochures. [Master Thesis, University of Helsinki]. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/146448386.pdf

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Sage.

Hofstede, G. J., Pedersen, P. B., & Hofstede, G. (2002). Exploring culture: Exercises, stories and synthetic cultures. Nicholas Brealey. Intercultural Press.

House, J. (2007). What Is an ‘Intercultural Speaker’?. In E. Alcón Soler, & M. Safont Jordà, (Eds.), Intercultural Language Use and Language Learning. Springer. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/JulianeHouse/publication/227102429_What_Is_an_'Intercultural_Speaker'/links/564dae3708ae1ef9296ac16a/What-Is-an-Intercultural-Speaker.pdf

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, G. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations. Sage.

Kabasakal, H., Asugman, G., & Develioğlu, K. (2006). The role of employee preferences and organizational culture in explaining e-commerce orientations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(3), 464-483.

Karacay-Aydin, G., Akben-Selcuk, E., & Aydin-Altinoklar, A. E. (2009). Cultural Variability in Web Content: A Comparative Analysis of American and Turkish Websites. International Business Research, 3(1).

Kuo, E. C. Y., & Chen, P. S. J. (2022). Social Policy Planning in Singapore. Communication Policy and Planning in Singapore, 53-63.

Lailawati, S. (2005). High/low context communication: The Malaysian Malay style. In Proceedings of the 2005 Association for Business Communication Annual Convention (Vol. 111). Association for Business Communication.

Lehtonen, M. (2000). Cultural Analysis of Texts.

Lewis, R. D. (2004). Communicating Cultural Diversity in International Tourism. In WTOOMT Observations on International Tourism Communications. Report from the First World Conference on Tourism Communications, Madrid: WTO-OMT (pp. 125-132).

Loda, M. D. (2011). Comparing web sites: An experiment in online tourism marketing. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(22). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=be7794c1864f08aa1e7c05850313a3e184892c28

Louhiala-Salminen, L., & Kankaanranta, A. (2011). Professional Communication in a Global Business Context: The Notion of Global Communicative Competence. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 54(3), 244-262.

Malaysia Healthcare Travel Council. (2020). Deferment of the Malaysia year of healthcare travel campaign 2020 by Malaysia Healthcare Travel Council. https://www.mhtc.org.my/2020/03/18/deferment-of-the-malaysia-year-of-healthcare-travel-2020-myht2020-campaign-by-the-malaysia-healthcare-travelcouncil-mhtc/

Mason, A. (2014). Overcoming the ‘dual-delivery’stigma: A review of patient-centeredness in the Costa Rica medical tourism industry. The International Journal of Communication and Health, 4, 1-9. https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=communication_faculty

Matsumoto, D., & Juang, L. (2007). Culture and psychology (4th Ed.). Wadsworf.

Mithun, M. (2004). The Value of Linguistic Diversity: Viewing Other Worlds through North American Indian Languages. In A. Duranti (Ed.), A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology. Blackwell's.

Mocini, R. (2009). La Comunicazione Turistica: Strategie Promozionali e Traduttive [Tourist Communication: Promotional and Translation Strategies]. [PhD Thesis, University of Sassari]. https://iris.uniss.it/bitstream/11388/251078/1/Mocini_R_Tesi_Dottorato_2010_Comunicazione.pdf

Neuliep, J. W. (2017). Intercultural Communication Apprehension. The International Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication.

Oswal, S. K., & Palmer, Z. (2018). Oswal, S. K., & Palmer, Z. (2018). Can diversity be intersectional? Inclusive business planning and accessible web design internationally on two continents and three campuses. Proceedings of the 83rd Annual Conference of the Association for Business Communication. SIAS Faculty Publications. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/ias_pub

Oxford Analytica. (2020). COVID-19 may hurt Singapore most in South-east Asia. Expert Briefings. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/

Peterson, B. (2004). Cultural Intelligence: A Guide to Working with People from Other Cultures Paperback. Intercultural Press. https://www.amazon.com/Cultural-Intelligence-Working-People-Cultures/dp/1931930007

Qiao, G., Song, H., Prideaux, B., & Huang, S. S. (2023). The "unseen" tourism: Travel experience of people with visual impairment. Annals of Tourism Research, 99, 103542.

Sari, R. P., & Putra, F. K. K. (2019). The design characteristics of Indonesian and German hotel websites: A cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Applied Sciences in Tourism and Events, 3(1), 93-107.

Şerbănescu, A. (2007). Cum gândesc şi cum vorbesc ceilalţi: prin labirintul culturilor [How others think and speak: through the labyrinth of cultures]. Polirom.

Sharma, A., Vishraj, B., Ahlawat, J., Mittal, T., & Mittal, M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 outbreak over Medical Tourism.

Stoian, C. E. (2015). The discourse of tourism and national heritage: A contrastive study from a cultural perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. https://www.cambridgescholars.com/resources/pdfs/978-1-4438-8219-4-sample.pdf

The Star. (2023). A stronger, more positive comeback for Malaysia's medical tourism. https://www.thestar.com.my/lifestyle/travel/2023/01/02/a-stronger-more-positive-comeback-for-malaysia039s-medical-tourism

The Straits Times. (2022). Budget debate: $500 million package to help S'pore's aviation sector recover from Covid-19. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/politics/budget-debate-new-500-million-package-to-help-aviation-sector-recover-from-covid-19

Usunier, J. C., & Roulin, N. (2010). The Influence of High- and Low-Context Communication Styles On the Design, Content, and Language of Business-To-Business Web Sites. Journal of Business Communication, 47(2), 189-227.

Van Dijk, T. (2009). Society and Discourse. How Context Controls Text and Talk. Cambridge.

Wan Abdul Halim, W. F. S., Zainudin, I. S., & Mohd Nor, N. F. (2021). A Functional Analysis of Theme and Thematic Progression of Private Hospital Websites. 3L The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 27(3), 73-97.

Wan Abdul Halim, W. F. S., Zainudin, I. S., & Mohd Nor, N. F. (2022). Multimodal Communicative Acts of Thailand's Private Hospital Website Promoting Medical Tourism. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies, 22(2), 88-110.

Woodward-Smith, E., Alexandra, C., Octavian, M., & Mihaela, M. E. (2021). Multiculturality and Discourse Awareness in the Media. Multicultural Discourses in Turbulent Times, 2(11).

Wu, G. (2018). Official websites as a tourism marketing medium: A contrastive analysis from the perspective of appraisal theory. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 10, 164-171.

Wurtz, E. (2005). Intercultural Communication on Web sites: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Web sites from High-Context Cultures and Low-Context Cultures. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(1), 274-299.

Xu, A., Johari, S. A., Khademolomoom, A. H., Khabaz, M. T., Umurzoqovich, R. S., Hosseini, S., & Semiromi, D. T. (2023). Investigation of management of international education considering sustainable medical tourism and entrepreneurship. Heliyon, 9(1), e12691.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

29 November 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-131-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

132

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-816

Subjects

Accounting and finance, business and management, communication, law and governance

Cite this article as:

Wan Abdul Halim, W. F. S. B., Yaacob, A. B., & Rahman, N. A. B. A. (2023). Medical Tourism Digital Promotion: A Contrastive Study From an Intercultural Communication Perspective. In N. M. Suki, A. R. Mazlan, R. Azmi, N. A. Abdul Rahman, Z. Adnan, N. Hanafi, & R. Truell (Eds.), Strengthening Governance, Enhancing Integrity and Navigating Communication for Future Resilient Growth, vol 132. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 659-681). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2023.11.02.52