Development of Necessary Professional Competencies Among Students in a Kindergarten Teacher Training Program

Abstract

This article addresses preliminary findings based on a mixed methods study, using questionnaire, examining future orientation, sense of coherence, and self-efficacy and changes in these competencies of students in a kindergarten teacher training (KTE) program. 40 students, with different seniority, enrolled in the program, constituted the research population. Research tools included a questionnaire regarding the way they imagined their future as teachers. Open qualitative answers were recorded into ordinal scales and analysed. A set of factors was built across background categories, e.g., gender and age, academic background and experience. More personal sections included open self-reported hopes and fears - hopes for professional promotion, personal achievements, academic successes, and income increase; and fears regarding financial stability, employment success, personal goals and graduation from the program. These binary items were used to map respondents on two unsupervised dimensions within a multidimensional scaling (MDS) framework. The findings showed various combinations of hopes accompanied by fears. Interestingly, the only difference was that older students reported more professional promotion than academic graduation expectations compared to younger students. The research may contribute to changes KTE programs, allowing students to present their perceptions regarding their professional future, and the findings can help adapt training programs around the world.

Keywords: Sense of Coherenceprofessional developmentsecond careeron-the-job trainingKTE programs

Introduction

This study addresses kindergarten teacher-assistants with no academic education and their ability to cope with an academic training program while integrating full-time work and managing their own household. Future orientation is addressed in this context because it influences the perception of individuals' self-efficacy and sense of coherence and their translation into behaviours that promote these goals consistently and continuously. To date, these competencies have been explored among teachers, principals, and but not among kindergarten teacher-assistants.

In many countries (Chile, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Norway and Turkey), kindergarten teacher-assistants employed in early childhood education have no formal training at all (Bigras et al., 2010; Coley et al., 2016; Fuligni et al., 2009; Groeneveld et al., 2010; Ishimine & Tayler, 2012).

Furthermore, consistent findings also show that work experience does not contribute to the quality of interaction, but undergraduate training prior to starting work was found to correlate to the quality of interaction in Denmark, Portugal and the United States (Barros & Leal, 2011; Guo et al., 2010; Pianta et al., 2005).

These days, education systems are required to prepare for a different school year. Time spent within educational frameworks will be differential and the need to provide a professional response to changing needs requires training and responsiveness while 'on the move'. The importance of developing supportive relationships is emphasized with the increased and acute need for continuity of education frameworks and response to children throughout the educational continuum (Reich & Mehta, 2020).

Problem Statement

To examine academic self-efficacy, sense of coherence and future orientation of assistants and auxiliary personnel intending to be kindergarten teachers during their training.

To examine formulation and consolidation of their sense of academic self-efficacy, sense of coherence and future orientation during their training program, at the start, during and after, when students are integrated into work.

Research Questions

How does the training program affect development of its students’ academic self-efficacy, sense of coherence and future orientation?

Purpose of the Study

In 2015, Oranim College in Israel, launched a training program, adapted to experienced kindergarten teacher-assistants without formal academic training, suited to for their work in the field of early childhood. In this program, assistants continue working and receive training and instruction in their workplace by a pedagogical instructor from the College.

This study seeks to examines how this unique training program influences’ future orientation, self-efficacy, sense of coherence in learning situations of teacher-assistants participating in the program.

Research Methods

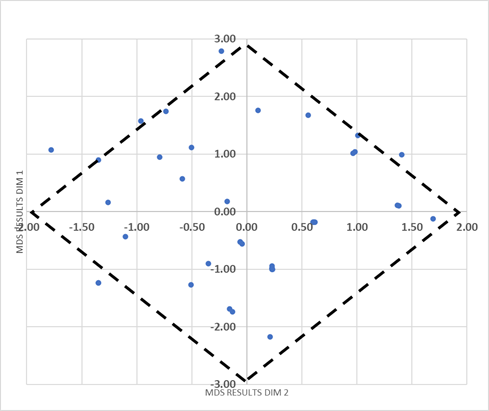

The empirical study was based on a sample of students who started a training program to become kindergarten teachers in the future, many of whom were teaching assistants to kindergarten teachers in their first career. The sample comprised of 40 students who responded to a survey of mixed qualitative and quantitative questions. We used a mix of statistical techniques to assess various aspects of the students' perceptions of their second career. For quantitative data, we composed several research indicators, each constructed as a representative scale for a unique and distinct aspect of the second career. We then analysed these indicators according to our theoretical expectations. The qualitative answers were reviewed and evaluated on ordinal mainly binary scales according to the context of these answers. These ordinal scales were used to build a proximity mapping within a multi-dimensional scaling framework. Some conclusive remarks concluded the empirical section with a discussion on their implementation and limitations of the study.

Findings

Samples

The sample for this study was drawn from a group of 40 students that decided to undertake a second career in kindergarten teaching. Out of these 40 students, only one was male and the others were females, see Table

Indicators

Table

The Qualitative Study

As part of the research regarding the development of professional competencies for second career kindergarten teachers, based on the 40 survey respondents, I developed a methodology to handle open questions, that is, questions that left an open space for respondents to fill in qualitative responses. The current survey included two open questions based on Seginer’s hopes and fears scales (1998). Participants read the following questionnaire statement: “people often fear for their future. Most people describe their future thoughts through hopes and fears”. Following this statement, participants were asked to write in detail their future hopes and to reflect about the age they would hope to meet these expectations. Participants were then asked to reflect about their fears of the future and write them down while mentioning the age that related to their fears.

The two open questions enabled a better understanding of the possible future participants faced. A content analysis was performed. we compiled the corpus by using search terms pertaining to specific categories. The following list shows content analysis results. In this list, different identified aspects of the two dimensions of the future, hope and fear, are presented where a positive response was coded as one in a zero or one dichotomous scale. In other words, if one aspect of fear, for example, was present in a respondent's answer, the response was coded as one, and if not, the non-response was coded as zero.

A.

Four categories were identified: 1. professional success; 2. Personal success (family, home); 3. Academic education; and 4. income.

-

Professional success: -

Student number 8: “I hope to open a clinic in the next few years.”

-

Student number 33: “My hopes are for professional development, stability at work, better income, inner peace and tranquillity.”

-

-

Personal success (family, home) -

Student number 1: “to succeed in my work as a kindergarten teacher and succeed in my personal life – have a family and partnership.”

-

Student number 16: “to build a family, find my professional way and stay curios.”

-

-

Academic education -

Student number 15: “I hope by age 30 to succeed in realizing my future dream, get a degree and work in the field.”

-

Student number 12: “hope by age 35 to study for a master’s degree.”

-

-

Income -

Student number 6: “hope in the future to have the financial ability to invest my time in raising my children, and then to become a kindergarten manager."

-

Student number 4: “finish a third degree.”

-

Four categories were identified: 1. financial fear; 2. job fulfilment/professional success/making an influence/failure; 3. personal fears/health/balancing family and work, not getting higher degree

Financial fear Student number 4: “fearing financial situation and failure at any age.”

Student number 14: “financial debts because of the studies.”

Job fulfilment/professional success/Making an influence/failure Student number 16: “will I succeed in doing what I have to do as a kindergarten teacher?”

Student number 21: “my fears are that I won’t succeed or will not be able to achieve my goals.”

Personal fears/health/balancing family and work Student number 6: "I’m afraid I don’t have an option to balance between having a family and my internship, so I’ll have to wait.”

Student number 22: “a great fear of mine is my health and the health of my family.”

Not getting higher degree Student number 10: “age 40 bothers me – I’m afraid for my job, where will I be in 10 years and will I be able to study for the second degree.”

Student number 13: “I’m afraid I won’t be able to continue to the second degree.”

Participants’ hopes for the future referred to the following issues: (1) professional success; (2) personal success (family, home); (3) academic education and (4) income. Twenty-nine participants (72.5%) mentioned professional success as part of their future hopes.

Table

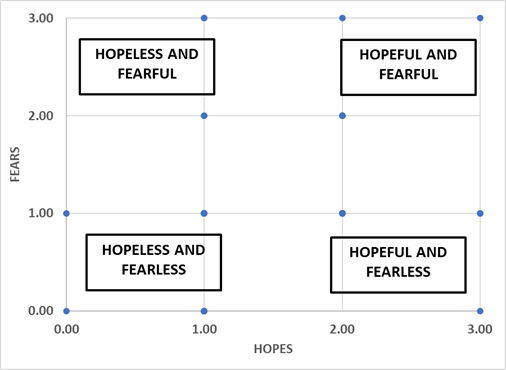

These binary values of fears and hopes were then used to map respondents within a multi-dimensional framework (Guttman 1968; Giguere 2006), as shown in figure

Conclusion

Respondents who studied more years scored their commitment higher than those who had lesser number of studied years, but had lower expectations

Older respondents reported less fear in comparison to younger respondents

Coherence was found higher among those whose position was full in comparison to those who had part-time position and a similar difference was found in the cognitive perception of future career

Respondents who developed more hopes are not fearless and those who were fearless are not hopeless.

Those findings were collected in a first of three surveys. Those results should be examined again in the end of the study.

References

- Barros, S., & Leal, T. (2011). Dimensões da qualidade das salas de creche do distrito do Porto [Quality dimensions of daycare centers in the district of Porto]. Revista Galego-Portuguesa de Psicoloxía e Educación, 9(2), 117-132.

- Bigras, N., Bouchard, C., Cantin, G., Brunson, L., Coutu, S., Lemay, L., Tremblay, M., Japel, C., & Charron, A. (2010). A comparative study of structural and process quality in center-based and family-based child care services. Child & Youth Care Forum, 39(3), 129-150. DOI:

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

- Coley, R. L., Votruba-Drzal, E., Collins, M., & Cook, K. D. (2016). Comparing public, private, and informal preschool programs in a national sample of low-income children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36, 91-105.

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334. DOI:

- Fuligni, A. S., Howes, C., Lara-Cinisomo, S., & Karoly, L. (2009). Diverse Pathways in Early Childhood Professional Development: An Exploration of Early Educators in Public Preschools, Private Preschools, and Family Child Care Homes. Early Education and Development, 20(3), 507-526.

- Giguere, G. (2006). Collecting and Analyzing Data in Multidimensional Scaling Experiments: A Guide for Pschologists Using SPSS. Tutorial in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 21(1), 26 – 37.

- Groeneveld, M. G., Vermeer, H. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Linting, M. (2010). Children's wellbeing and cortisol levels in home-based and center-based childcare. Early childhood research quarterly, 25(4), 502-514.

- Guo, Y., Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2010). Relations among preschool teachers' self-efficacy, classroom quality, and children's language and literacy gains. Teaching and Teacher education, 26(4), 1094-1103.

- Guttman, L. A. (1968). General Nonmetric Technique for Finding the Smallest Coordinate Space for a Configuration of Points. Psychometrika 33, 469 - 506.

- Ishimine, K., & Tayler, C. (2012). Family day care and the National Quality Framework: Issues in improving quality of service. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 6(1), 45-61.

- Mead, A. (1992). Review of the development of multidimensional scaling methods. The Statistician, 41(1), 27 - 39.

- Pianta, R., Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Bryant, D., Clifford, R., Early, D., & Barbarin, O. (2005). Features of Pre-Kindergarten Programs, Classrooms, and Teachers: Do They Predict Observed Classroom Quality and Child-Teacher Interactions? Applied Developmental Science, 9(3), 144-159.

- Reich, J., & Mehta, J. (2020). Imagining September: Principles and Design Elements for Ambitious Schools During COVID-19. https://edarxiv.org/gqa2w

- Seginer, R. (1988). Adolescents' orientation toward the future: Sex role differentiation in a sociocultural context. Sex Roles, 18, 739-757. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 March 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-103-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

104

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-536

Subjects

Education, teacher, digital education, teacher education, childhood education, COVID-19, pandemic

Cite this article as:

Zaidel, M., & Stan, C. N. (2021). Development of Necessary Professional Competencies Among Students in a Kindergarten Teacher Training Program. In I. Albulescu, & N. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2020, vol 104. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 29-43). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.03.02.4