Effect of Gratitude in the Relationship Between Servant Leadership and Organizational Identification

Abstract

Positive psychology and its organizational reflection on organizational behaviour, namely positive organizational behaviour, underlines the importance of positive forms of leadership in forming positive organizational climates. Servant leadership is one of the most important positive forms of leadership that effects positive feelings like gratitude and results in organizational identification. Moreover, gratitude can effect as a mediator in the relationship between servant leadership and organizational identification. To test the propositions, a field survey using questionnaires was conducted on 173 companies. In this study 503 usable surveys were applied. The obtained data from the questionnaires were analysed through the SPSS statistical packaged software. After the validation of measures, a series of regression analysis was conducted to test the hypotheses and to define the direction of relations. Analyses results highlighted the relationship among the servant leadership, gratitude and organizational identification. Findings have found to be consistent with the proposition that gratitude acts as a mediator in the relationship between servant leadership and organizational identification.

Keywords: Servant LeadershipGratitudeIdentification

Introduction

Positive leadership styles have increasingly became popular in the last decades. Scholars such as Ehrhart (2004), Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May and Walumbwa (2005) and Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, (2008) are among the kind of researchers that focused especially on positive kinds of leadership. This focus on positive leadership styles can be considered as the evidence of increasing emphasis on positivity in professional life (Walumbwa et. al., 2010). In the extant literature, it is shown that leaders possessing positive properties, goals and values often have the ability to positively affect their followers’ states and performances (Peterson, Walumbwa, Byron & Myrowitz, 2009; Walumbwa et. al., 2010).

Servant leadership regarded as one of the most proper kinds of leadership for positive organizational atmospheres and it promotes flourishing of individuals. It is a unique kind of leadership that is against self-interest in organizational settings. According to Greenleaf servant-leader has the natural feeling of serving other people (Greenleaf, 1977, p.13). Serving others is an inner motivation for the leader that stems from leaders’ spiritual insights and humility (Graham, 1991). Servant leaders treat their followers with compassion and they are not obsessed with hierarchy. Servant leaders exercise both the ends and means of the acts of serving followers in congruent with moral and ethical principles (Graham, 1991; Yukl, & Falbe, 1990).

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Servant Leader

Servant-leadership is a leadership style so often misinterpreted by those who reject existence of this leadership style. Servant-leaders are always accountable for the results of their leadership to third parts such as stockholders, clients, owners etc. depending upon the operational structure and purpose of the organization (Page, and Wong, 2000). It is consultative, relational and self-effacing in nature. Servant leader is an empowerer and developer seeking to inspire followers toward their best fit in fulfilling the vision. They support their followers in finding purpose and inspire them in achieving their goals (Winston, 2003). On the one hand they are good and reliable problem solvers. They are competent in taking input and carefully weighting options, they are also good at understanding what is happening within the organization. And they can communicate their ideas effectively, give power to others, move different types of people forward in achieving results (Page, and Wong, 2000).

Servant leaders put their followers’ benefit in front of their own and they do not withdraw themselves to their ivory towers. They listen to their followers, they are empathetic. They are eager to help others, they give importance to follower’s education, they have a meaningful vision regarding their organization, they give importance to gaining trust of their followers and they do their best to empower them (Burrell, and Grizzall, 2010). In fact, servant leaders portray a resolute conviction and strong character by both taking the role and the nature of a servant. Unlike most other leaders they do not give importance to power distance, they do not exaggerate status symbols as a means of establishing distance between themselves and their followers and they treat all people with radical equality, behaving others as equal partners. In the literature this type of relationship is described as a covenant-based relationship, namely, an intense personal bond marked by shared values, open-ended commitment, mutual trust, and concern for the welfare of the other party. This bond produce a relationship that can not be easily stretched to breaking point (De Pree, 1989). This strong bond between leader and his follower may result in positive feelings, especially, sympathy towards each other and followers will presumably feel gratitude towards their emphatic, empowering and flourishing leader.

Covey (1990) claimed that organizations become more effective and profitable when individuals perform their tasks without continually being monitored, evaluated, corrected, or controlled by superiors. He further claimed that providing training in the principles embodied in servant leadership could assist in establishing this type of an environment. Servant leaders bring the discipline necessary to set goals in guiding his followers towards organizational goals. Page and Wong (2000) suggest that servant leaders bring focus, clarity and realism to goal setting.

The focus of servant leadership theory is prioritization of follower’s interests (Joseph & Winston, 2005). It has been proposed that the leader’s service to the followers results in reciprocal service to the leader by the followers (Winston, 2003). Followers often reciprocate the support they get from their leaders with prosocial behaviours towards other members in their surroundings (Ehrhart, 2004). Servant leader’s genuine love towards his employees and his concern for their welfare, often result in the development of unspecified obligations on the side of employees to answer their leaders’ favours. Successful social exchanges create feelings of personal obligation, gratitude, and trust on an ongoing basis (Blau, 1964, p. 94). Thus, it can be expected that servant leaders’ empowering and supportive behaviours will probably create a grateful mood on the part of the follower. Followers respond to the behaviour of their leaders by gratitude and starts to behave in a good manner towards both his leader and organization. Consistent with norm of reciprocity (Gouldner 1960), support perceived by followers obligates them to help, or at least not to harm the organization (Gouldner 1960). Leader–member exchange theory also enlightens our understanding about feelings of gratitude in the relationship between servant leader and his followers. Leader member exchange theory claims that when there is a leader- member exchange relationship as in the relationship between servant leader and his followers, leaders and members move beyond a relationship that is characterized as “working for” to one that is characterized as “working together” (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). From followers’ point of view, the key features of a high-quality supervisor–subordinate relationship involves mutual support, trust and respect. And it can be proposed that this high level of trust and respect would result in high levels of gratitude towards the leader.

Gratitude

One of the most important emotion experienced in positive atmospheres is feeling of gratitude. According to Wood, Froh, and Geraghty (2010), gratitude is a life orientation toward noticing and appreciating the positive in the world. Gratitude contributes to the realization that happiness is not contingent upon materialistic happenings in life, and it is nourished from being embedded in caring networks of giving and receiving (Froh, et al., 2010). According to Chang (2012) there are two different ways gratitude improves people’s quality of life. The first way is the emotional support path, namely, psychological well-being. The second way is increasing social connections. Gratitude extends with these connections and allows people maintain a better life.

Gratitude helps people appreciate the gifts of the current time period and makes people experience freedom from past regrets and future anxieties. Gratitude both nurtures social relationships through its encouragement of reciprocal, prosocial behavior between a benefactor and recipient (Algoe & Haidt, 2009; Emmons & McCullough, 2004) and also it increases likelihood that the recipient will assist an unrelated third party in the future (Bartlett and DeSteno 2006). Thus, it is expected that individuals experiencing gratitude and behaving benevolently toward other people increases their social bonds and these extended social bonds help people to better adapt to differences and combat with the difficulties of life.

Furthermore, gratitude also has the capacity to promotes positive outcomes in organizational settings. McCullough et al. (2002) suggested that gratitude encourages individuals to behave in a prosocial way towards even unrelated third parties. That is why people feeling grateful both appreciate their counterparts and act accordingly and feel grateful towards towards life as a general attitude. And also they act more positively compared to people who experiences feelings of gratitude less often. As a result, this atmosphere nourished from positive benefits of gratitude make organizations a better place to live.

Gratitude also increases followers sense of interpersonal trust and imbeddedness in caring relationships (Dunn and Schweitzer 2005). In this sense it seems meaningful to anticipate that followers feeling gratitude towards their leaders will feel more identified with their leaders and organizations.

Organizational Identification

Identification is the extent to which an individual defines himself or herself in terms of membership in his/her organization (Ashforth, Harrison, & Corley, 2008). It is concerned with the question “Who am I in relation to the organization?” (Pratt, 1998). And members are accepted to have high levels of identification with their organization when they define themselves at least partly in terms of what their organization represents. When employees identify themselves with an organization, they incorporate the organization’s identity into their own social identity. As a result of identification, employees tend to be more committed, tend to engage in citizenship behaviour more often, and they are less likely to leave their organization. Moreover, as members increasingly identify with an organization, the individual self-perceptions of the members tend to become depersonalized such that members see themselves as interchangeable representatives of the social category that is the organization (e.g., Turner, 1985).

In the extant literature we come across three main dimensions regarding organizational identification. Following Patchen’s (1970) identification theory, organization identification includes three components: (1) feelings of solidarity with the organization; (2) attitudinal and behavioural support for the organization; and (3) perception of shared characteristics with other organizational members all of which contributes to feeling of oneness with the organization. On the one hand, organizational identification has been linked to a variety of work attitudes, behaviours, and outcomes that support the organization such as individual decision making (Cheney, 1983) commitment to common goals (McGregor, 1967) etc.

According to extant literature, leaders are able to shape followers’ identities (Avolio, Walumbwa, & Weber, 2009; Ellemers, De Gilder, & Haslam, 2004; Lord & Brown, 2001), including organizational identification. Leaders in an organization play an important role in shaping employees feelings and ideas in their daily work lives, hence leaders’ behaviors may shape how employees view their relationship and social identifications with their work organization.

Exchange relationships with one’s organization and supervisor are of great significance to subordinate employees (Jawahar & Carr, 2007). These relationships often result in feelings of personal obligation, gratitude, and trust (Blau, 1964, p. 94). That is why in establishing our research model we presumed a positive relationship between servant leadership and gratitude. As the supervisor/leader is perceived as the symbolic agent of the organization, identification with the former may be generalized to identification with the latter. Hence we expect that gratitude felt towards that symbolic agent will effect to commitment and identification towards the organization. In the extant literature there are studies that supports our point of view. For example; Barlet & DeSteno (2006) found evidence that gratitude fosters a desire to spend time with one’s benefactor, grateful individuals engage in socially inclusive behaviours specifically toward their benefactor even when those actions come at a cost to oneself. That is to say gratitude creates a special link between leader and its followers which result in a higher level of connection which can turn into commitment or identification in time. As stated previously, experiencing gratitude directly facilitates recognition of a kind act and repayment of the favour. This has been illustrated in controlled lab settings in which feeling grateful leads one to reciprocate with costly helping behaviours (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006; Tsang, 2006) and to act cooperatively in economic exchanges (DeSteno et al. 2010). Hence in our study we wanted to search for the relationship between servant leadership and feelings of gratitude in an organization. Thus our first hypothesis was:

Moreover, there are studies claiming that the supervisory relationship is likely to be psychologically connected to the organization given that the organization serves as the "home" for the relationship and the supervisory relationship's goals support the goals of the organization (Katz & Kahn, 1978). Although the link between servant leadership and organizational identification has not taken much place in the literature yet. There are some supporting studies regarding the relationship between servant leadership and organizational commitment which is an akin concept with organizational identification. Regarding the relationship between organizational commitment and identification, O’Reilly and Chatman (1986) emphasizes that commitment is a psychological bond between the employee and the organization. They also clam that three forms of this bond can take place: compliance, identification and internalization. They define identification as the process of “an individual accepting influence from a group (organization) in order to establish and maintain a relationship”. Hence, an individual may respect a group’s values without adopting them, as opposed to internalization (O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). To give an example for the relationship between servant leadership and organizational commitment; a recent study made by Hoveida in 2011 investigated the relationship among the characteristics of servant leadership and the organizational commitment at University of Isfahan and findings of the study showed that there is a significant relationship among the characteristics of servant leadership and organizational commitment. And findings of the study about the presence of relationship among the characteristics of servant leadership and staff organizational commitments were in line with the findings of Barbuto and Wheeler (2006), Ehrhart (2004), Joseph and Winston (2005). Considering our literature review, in our model it is proposed that servant leadership may have a direct effect on organizational identification, so we suggested that;

As mentioned before, McCullough et. al., (2002) suggested that gratitude also induces individuals to behave benevolently to the benefactor and even to an unrelated third party. So we expected that in organizational settings people may behave with greater identification towards their organizations’ itself in case they feel their organizations’ behave them with care and intimacy. According to Ehrhart (2004), compared to other styles of leadership servant leadership ensures high levels of positive emotions in organizations including organizational commitment, organizational identification, satisfaction and gratitude felt towards the leader. Due to the fact that gratitude increases followers sense of interpersonal trust and imbeddedness in caring relationships (Dunn and Schweitzer, 2005), we anticipated that followers feeling gratitude towards their leaders would feel more identified with their leaders and organizations. Thus, we proposed that gratitude will result in higher levels of organizational identification. So our fifth hypothesis was;

H5: There is a meaningful relationship between gratitude felt by followers and the three sub dimensions of organizational identification experienced by followers.

H6: Gratitude of followers’ act as a mediator in the relationship between servant leadership and sub dimensions of organizational identification experienced by followers.

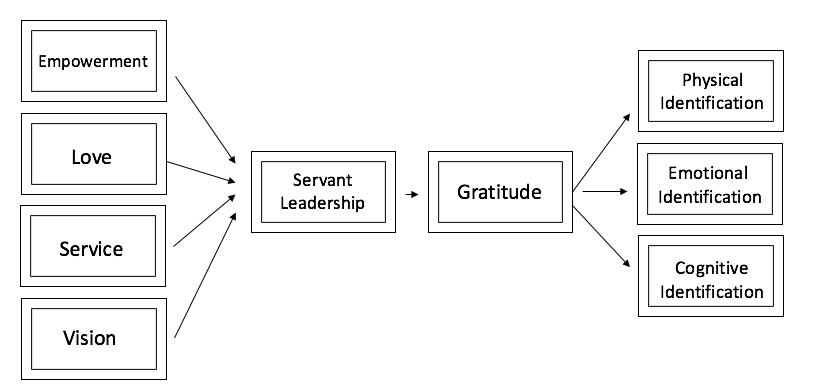

Research model regarding this study has been shown in the following in Figure

Research Method

Sample and Data Collection

In our study, we used easy sampling method in order to collect our survey data. We applied face to face surveys to our applicants. Exploratory exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted to see if the observed variables theoretically loaded together and validity and reliability values were evaluated. And structural equation modelling technic has been used in testing the hypothesis. Responses to the survey questionnaire were assessed on a five-point Likert Scale. Survey of the study was applied on production and service sectors in Marmara Region in Turkey. And 173 companies were reached and 503 usable surveys have been obtained.

Analyses

In our survey questions, we used Aslan and Özata’s (2011) servant leadership scale which was derived from the original scales of Dennis and Winston (2003) and Dennis and Bocernea (2006). We used 4 questions for service dimension, 7 questions for empowerment dimension and 3 questions for vision dimension. For measuring gratitude, we used 6 questions from the Gratitude Questionnaire (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002) and for physical identification we used 6 questions from Brown and Leigh's measure of work intensity, we also barrowed 6 questions from Russell and Barret’s (1999) measure for emotional identification and 6 questions from Rothbard's (2001) measure for cognitive identification. The Cronbach’s Alpha values for each factors exceeds 0,70, which indicates the reliability of scales used in that survey.

Exploratory factor analysis results related to the variables used in our study are given in Table

When correlation results are examined, it is seen that all our hypothesis are accepted. Moreover, when the correlation relationship between demographic variables and research dimensions are examined it is confirmed that as employee numbers increase in an organization the perception regarding the availability of servant leadership, feelings of gratitude and identification decreases. This inverse relationship is highest in the relationship with emotional identification. Furthermore the relationship with women workers and feelings of gratitude is stronger compared to the relationship with men. And total experience positively effects servant leadership perceptions, feelings of gratitude and identification. And this relationship is strongest with emotional identification.

Findings

In this study, regression analysis is also conducted to test the hypotheses and to define the direction of relations. When Table

Moreover, according to analysis results gratitude has a meaningful effect on the third sub dimensions of identification; physical identification (Adjusted R2:,238, Sig:,001), emotional identification (Adjusted R2:,433 Sig:,001) and cognitive identification (Adjusted R2:,299, Sig:,001) so H5 is also accepted. When the mediator effect of gratitude in the relationship between servant leadership and organizational identification has been investigated we saw that gratitude act as a perfect mediator in the relationship between servant leadership and cognitive and emotional identifications, but it acts as a partial mediator between servant leadership and physical identification. Moreover, when organizational identification is examined in one dimension, gratitude acts as a partial mediator. So H6 is partially supported.

Conclusion and Discussions

This survey, which is conducted on manufacturing and service sectors in Turkey, highlighted the relationship among servant leadership style, gratitude felt by followers and organizational identification of followers. The most striking result that emerged from this study is that servant leadership is effective on both gratitude felt by followers and identification felt towards organization. Furthermore, gratitude acts as a partial mediator in the relationship between servant leadership and organizational identification. As mentioned before there are three kinds of identification felt towards the organization; physical identification, cognitive identification and emotional identification. Interestingly, role of gratitude as a mediator is more prominent in cognitive and emotional identification but it is partial in physical identification. Results show that benevolent acts of servant leadership touches emotions and perceptions of followers and make them feel more positively towards their leaders. Perhaps, creating and nourishing an organizational culture that encourages people to feel gratitude towards each other and towards their organization will be meaningful to increase identification of members but but these grateful feelings does not necessarily mean that followers will feel physical identification. More effort may be needed in order to ensure physical identification. And it would be meaningful to assume that physical identification is more difficult to establish. Adoption of servant leadership style by all management levels and by human resources practitioners may be effective in ensuring physical identification of members. Moreover, beyond a supporting leadership style, appealing human resource applications, material awards, job security, promotion prospects and a challenging work will probably contribute to physical identification of members.

The nature of the concept of gratitude can be effective in these result. All people do not experience feelings of gratitude in the same way hence do not reply to this feeling behaviourally. Also while some people innately show stronger tendency to feel gratitude and some people may be less inclined to feel gratitude. And the same kind of leadership may be less effective on the behaviours and attitudes of people who are innately less inclined to feel gratitude. In further studies these tendencies of people may be taken into consideration.

Moreover, this survey is conducted on a limited number of sectors- only on production and service sectors- that is why findings might not be transferable to all types of sectors and organizations. Thus, further researches can be conducted on other sectors and, also in different countries for the generalizability of findings. In this study data have been collected from white collar workers so we can not generalize our findings to blue collar workers, may be a different study can be applied in order to make deduction for blue collar workers.

References

- Algoe, S. B., & Haidt, J. (2009). Witnessing excellence in action: The ‘other-praising’emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. The journal of positive psychology, 4(2), 105-127.

- Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of management, 34(3), 325-374.

- Aslan, Ş., & Özata, M. (2011). SaĞlık Çalışanlarında Hizmetkâr Liderlik: Dennis-Winston ve Dennis-Bocernea Hizmetkâr Liderlik Ölçeklerinin Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Araştırması. Journal of Management & Economics, 18(1).

- Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Weber, T. J. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual review of psychology, 60, 421-449.

- Barbuto Jr, J. E., & Wheeler, D. W. (2006). Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group & Organization Management, 31(3), 300-326.

- Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological science, 17(4), 319-325.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Transaction Publishers.

- Burrell, D., and Grizzell, B. C. 2010. Do You Have the Skills of a Servant-Leader? Nonprofit World, 28(6), 16-17.

- Cheney, George. (1983). “On the various and changing meanings of organizational membership: a field study of organizational identification.” Communication Monographs 50 (4), 342-362.

- Covey, S. R. (1990). Principled central leadership. New York: Summit.

- De Pree, M. (1989). Leadership is an Art. New York: Dell Publishing.

- Dennis, R.S. ve Bocernea, M. (2005). Development of the servant leadershipvassessment instrument. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26 (8), 600-615.

- Dennis, R., & Winston, B. E. (2003). A factor analysis of Page and Wong’s servant leadership instrument. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24(8), 455-459.

- DeSteno, D., Bartlett, M. Y., Baumann, J., Williams, L. A., & Dickens, L. (2010). Gratitude as moral sentiment: emotion-guided cooperation in economic exchange. Emotion, 10(2), 289.

- Dunn, J., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2005). Why good employees make unethical decisions: The role of reward systems, organizational culture, and managerial oversight. Managing organizational deviance, 39-68.

- Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit‐level organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 57(1), 61-94.

- Ellemers, N., De Gilder, D., & Haslam, S. A. (2004). Motivating individuals and groups at work: A social identity perspective on leadership and group performance. Academy of Management review, 29(3), 459-478.

- Emmons, R.A., & McCullough, M.E. (2004). The psychology of gratitude. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Froh, J. J., Bono, G., & Emmons, R. (2010). Being grateful is beyond good manners: Gratitude and motivation to contribute to society among early adolescents. Motivation and Emotion, 34(2), 144-157.

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The leadership quarterly, 6(2), 219-247.

- Graham, J. W. (1991). Servant-leadership in organizations: Inspirational and moral. The Leadership Quarterly, 2(2), 105-119.

- Jawahar, I. M., & Carr, D. (2007). Conscientiousness and contextual performance: The compensatory effects of perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(4), 330-349.

- Joseph, E. E., & Winston, B. E. (2005). A correlation of servant leadership, leader trust, and organizational trust. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(1), 6-22.

- Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (Vol. 2). New York: Wiley.

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of personality and social psychology, 82(1), 112.

- O'Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of applied psychology, 71(3), 492.

- Page, D., & Wong, T. P. (2000). A conceptual framework for measuring servant leadership. The human factor in shaping the course of history and development, 69-110.

- Patchen, Martin. (1970). Participation, achievement, and involvement on the job. New Jersey: Prentice- Hall.

- Peterson, S. J., Walumbwa, F. O., Byron, K., & Myrowitz, J. (2009). CEO positive psychological traits, transformational leadership, and firm performance in high-technology start-up and established firms. Journal of management, 35(2), 348-368.

- Pratt, Michael G. (1998). “To be or not to be: central questions in organizational identification.” In Whetten, David A., and Paul C. Godfrey (eds.), Identity in organization, 171-207. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Rothbard, N. P. (2001). Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 655-684.

- Turner, J. C. (1985). Social categorization and the self-concept: A social cognitive theory of group behavior. In E. J. Lawler (Ed.). Advances in group processes: Theory and research (pp. 77-122). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of management, 34(1), 89-126.

- Walumbwa F.O., Wang P., Wang H., Schaubroeck J., Avolio B.J., 2010 "Psychological processes linking authentic leadership to follower behaviors (Retracted article. See vol. 25, pg. 1071, 2014)", Leadership Quarterly, 21(5), 901-914

- Winston, B. (2003). Extending Patterson’s servant leadership model. Retrieved April, 12, 2008.

- Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical psychology review, 30(7), 890-905.

- Yukl, G., & Falbe, C. M. (1990). Influence tactics and objectives in upward, downward, and lateral influence attempts. Journal of applied psychology, 75(2), 132.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 December 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-033-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

34

Print ISBN (optional)

--

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-442

Subjects

Business, business studies, innovation

Cite this article as:

Narcıkara, E. B., & Zehir, C. (2017). Effect of Gratitude in the Relationship Between Servant Leadership and Organizational Identification. In M. Özşahin (Ed.), Strategic Management of Corporate Sustainability, Social Responsibility and Innovativeness, vol 34. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 372-384). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.12.02.32