Abstract

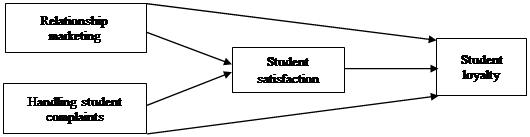

The study of service failure and recovery can be found in a variety of business sectors such as banking, health care and retail. However, the focus on higher education service failure and recovery is quite limited. Research into service recovery is critical because higher education providers and their students enter into a relationship for mutual satisfaction which could then lead to student loyalty. The goal of this study is to examine the effect of relationship marketing and handling student complaints resulting in student satisfaction and loyalty. A total of 100 appropriate respondents were selected using simple random sampling. Respondents were approached through a self-administered survey and the data was analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). The results show that all five hypotheses were supported meaning that relationship marketing and the handling of student complaints influence student satisfaction which in turn influences student loyalty. An excellent service recovery strategy established by higher education providers will encourage more students to enrol in the university and could help to increase student confidence, satisfaction and loyalty.

Keywords: Relationship marketinghandling student complaintsstudent satisfactionstudent loyalty

Introduction

Service recovery in general is a topic that has received a great deal of attention from academics as well as practitioners (Kim & Ulgado, 2012). Generally, service recovery refers to the actions taken by service firms when they have failed to provide the quality service expected by their customers. Generally speaking, delivering a superior quality service experience is very complicated and needs to be carefully designed and managed by service providers. If the service providers succeed in achieving customer satisfaction through a good service experience, this will attract more potential clients and increase customer loyalty which may result in greater business profitability. Service experience can be affected by many factors such as service operation, service quality and customer expectation (Aka et al., 2016; Chahal & Devi, 2015; Nauroozi & Moghadam, 2015). To sustain a superior quality service experience, the service providers must have background knowledge and good practices in place for service recovery.

The service recovery process usually starts with a service failure. Service failure exists when there is a gap between service performance and the consumers’ expectations (Lewis & Spyrakopoulas, 2001). Service failure is often the result of a lack of knowledge of a service which then leads to mistakes being made by the service providers, resulting in unhappy customers (Dabholkar & Spaid, 2012). As a result, customers feel dissatisfied or uncomfortable and this could lead to customers deciding to switch to other service providers. With this in mind, service providers must seriously tackle this issue because the customers might discuss their negative service experiences on social media and this could have a huge impact on the reputation of the service organization. Importantly, previous works have suggested that researchers should investigate service failure and service recovery within the education sector because few studies have concentrated on this area (Aka et al., 2016; Chandra et al., 2019; Nauroozi & Moghadam, 2015).

Past scholars have empirically examined service failure and recovery within a variety of sectors such as banking, health care and retail. However, the focus on higher education in relation to service failure and recovery is quite limited and needs to be investigated (Chahal & Devi, 2015; Mapunda & Mramba, 2018; Moyo & Ngwenya, 2018). In this competitive environment where students have many options open to them, factors that enable institutions to attract and retain students are required to be seriously studied as suggested by Hart and Nigel (2011). In the higher education sector, service failures may exist in the areas of teaching, examinations, libraries, laboratories, administration, infrastructure and other facilities like canteens, car parks and dormitories (Chalal & Devi, 2015; Voss et al., 2010).

To deal with behavioral responses from dissatisfied students, higher education providers should have an effective relationship between marketing and the handling of customer complaints because many scholars have mentioned that these two factors affect their satisfaction and loyalty within the education context and other areas (Aka et al., 2016; Alemu & Cordier, 2017; Filip, 2013; Mapunda & Mramba, 2018; Nauroozi & Moghadam, 2015; Ndubisi & Nataraajan, 2018). For instance, Nauroozi and Moghadam (2015) conducted a study on banking services in Iran, the result of which indicated a significant link between marketing and the handling of customer complaints and customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. The same results are evident in other sectors such as healthcare, hospitality and education in two regions of Malaysia (Ndubisi & Nataraajan, 2018).

The findings of this study will assist Universiti Tenaga Nasional (Uniten) and other higher education providers to create and enhance customer satisfaction and loyalty through a service recovery strategy (relationship marketing and handling of student complaints). An excellent service recovery strategy will attract more students to enrol in a university. Furthermore, the right strategy for service recovery could help to increase student confidence and satisfaction, increase revenue, reduce costs and increase employee morale and performance. In addition, the students will benefit from this process because their problems or concerns will have been addressed by the university in a very effective way. With good service recovery procedures, students will be happy to study at the university and the university will be the focus of positive word of mouth among students. Therefore, it could encourage new students to register at the university.

Problem Statement

In Malaysia, there are many choices for students to continue their study at higher education institutions. Department of Higher Education (2017) reported that there are 495 active private higher educational institutions and 20 public universities in Malaysia. The figures indicate that the higher education providers have stiff competition and therefore they must compete to attract and retain their students. Hart and Nigel (2011) proposed that the higher education providers should seriously study service failure because it will help to develop a much better service recovery strategy that may positively impact on customer satisfaction and loyalty. More importantly, higher education providers should not only analyze all types of service failures but also regularly check and monitor the behavioral responses of the students. As a result, they will have the chance to learn and minimize the occurrence of future service failures in their institutions. In Uniten, the statistics show that the number of service complaints from 2015 to 2018 increased. Because the study of service recovery can be found in sectors other than higher education institutions (Chahal & Devi, 2015; Mapunda & Mramba, 2018; Moyo & Ngwenya, 2018), this has motivated the researchers to conduct the current study.

Research Questions

The research questions in this current study are as follows: (i) What are the effects of relationship marketing and the handling of student complaints on student satisfaction and loyalty? and (ii) What is the effect of student satisfaction on student loyalty?

Purpose of The Study

The study objectives are to: (i) assess the relationship between relationship marketing and the handling of student complaints on student satisfaction and loyalty; and (ii) investigate the relationship between student satisfaction and student loyalty.

Research Methods

With the specific objective of obtaining an acceptable response rate, 125 potential respondents from Uniten, Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Campus (who have had service complaints) were approached using a self- administered survey using simple random sampling. Of these, only 100 completed questionnaires were collected for this study, hence the response rate was 80.0 per cent. To increase the validity of the questionnaire, this study was conducted using two basic procedures - expert opinion and a pre-test activity. The questionnaire was designed with easy to follow instructions and was comprised of three sections. In the first two sections, all items were related to exogenous and endogenous constructs, while Section Three comprised five demographic questions. In addition, one question was asked to identify the types of service complaint lodged by students. All 30 items in Section One and Section Two of the questionnaire were adapted from Komunda and Osarenkhoe (2012). Specifically, 7 items were used to measure relationship marketing and the handling of student complaints (9 items), student satisfaction (6 items) and student loyalty (8 items) and rated using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Figure

Findings

Of 100 respondents, 46 percent were male and 54 percent female. The majority of respondents were Malay (60 percent), followed by Indian and Chinese (34 percent and 6 percent respectively). With regards to age, only 6 percent of respondents were aged above 24. 67 percent of them were aged between 21 and 23. In relation to year of study, the majority of respondents were Year 3 students at 58 percent, followed by Year 1 students at 22 percent. Furthermore, 12 percent of respondents were from foundation programmes with the majority of them from Degree programmes at 69 percent. This study also recorded several complaints by the respondents. The types of complaints that were mentioned by respondents can be grouped into seven categories i.e. teaching (26 percent), administration (21 percent), examinations (20 percent), WiFi and accommodation (15 percent), library (8 percent), parking (7 percent), and computer labs (5 percent).

Common method variance may have existed because this study only used a single survey method to collect responses (Hair et al. 2006). With this in mind, at the data analysis stage, Harman’s (1967) one-test factor was applied to control the common method variance. The test yielded six factors accounting for 51.43 percent of the variance, and factor 1 accounted for 21.60 percent of the variance, less than the threshold value (Podsakoff et al. 2003). This indicates that, no common method bias affected the data. The next test referred to the measurement model and to analyse this, the current study applied PLS-SEM. Several tests such as internal consistency, indicator reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity tests were executed on the measurement model. Firstly, Table

The last test in the measurement model was to analyse the discriminant validity. The current study applied the test of Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) suggested by Henseler et al. (2015). According to Henseler at al. (2015), there are two approaches to examine discriminant validity. The first approach is known as the statistical test where the HTMT value should not be greater than the HTMT.85 value of .85 (Kline, 2011), or the HTMT.90 value of .90 (Teo et al., 2008). As shown in Table

After analyzing the measurement model, a second analysis was used to check the structural model using several tests such as estimating the path coefficients, the coefficient of determination (R2) and the effect size (f2). A bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 iterations was performed to measure the statistical significance of the weights of sub-constructs and path coefficients (Hair et al., 2017). Table

The detailed results of the structural model and hypotheses testing are also presented in Table

Furthermore, Hypothesis 2 (H2) was also supported by results (H2: b=.467, t = 7.243, sig ˂ .01). These results proved that student satisfaction was influenced by the handling of student complaints. These findings are in line with the past studies of Aka et al. (2016), Chandra et al. (2019), Haile (2019), Khoo et al. (2015), and Kumari Adikaram et al. (2016). The handling of complaints usually used by many service providers to solve service failure and help to manage post-purchase consumer dissatisfaction (Istanbulluoglu, 2017). The proper handling of complaints may provide a company with the opportunity to not only correct the problem, but also turn it into a satisfactory meeting among dissatisfied customers. Hornik et al. (2015) and Istanbulluoglu (2017), in their studies, clearly stated that the successful handling of complaints increases opportunities for repurchasing behavior, positive word-of-mouth, and increasing loyalty on the part of dissatisfied customers. It could also decrease marketing expenditure by reducing the cost of seeking out new customers. For instance, 484 respondents from 46 higher education institutions in Sri Lanka agreed that the handling of student complaints had a positive effect on student satisfaction (Kumari Adikaram et al., 2016). In addition, a study conducted by Haile (2019) at the Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia, found that the handling of student complaints had a significant influence on student satisfaction.

In addition, Hypothesis 3 (H3) that hypothesized that relationship marketing had a significant effect on student loyalty was supported (H3: b=.129, t = 1.969, sig ˂ .05). The results are similar to past studies conducted by Alrubaiee and Al-Nazer (2010), Abubakar and Mokhtar (2015), Firdaus and Kanyan (2014), Wali and Wright (2016), Wong et al. (2018) who confirmed that relationship marketing had a positive impact on student loyalty. For example, Abubakar and Mokhtar (2015) conducted a study at several universities in Nigeria which revealed the positive influence of relationship marketing on student loyalty. Similarly, Wong et al. (2018) also demonstrated a positive relationship between relationship marketing and student loyalty. A total of 291 respondents from leading private universities in Hong Kong participated in their study.

Moreover, Hypothesis 4 (H4) and Hypothesis 5 (H5) which hypothesized that handling student complaints and student satisfaction influence student loyalty were also supported by results (H4: b=.338, t = 4.204, sig ˂ .001; H5: b=.437, t = 5.593, sig ˂ .01) respectively. These results proved that relationship marketing and the handling of student complaints have a positive influence on student satisfaction. These findings are consistent with the findings of Abubakar and Mokhtar (2015), Ali et al. (2016), Wali and Wright (2016), Wong et al. (2018), Manzuma-Ndaaba et al. (2018) and Chandra et al. (2019). A study administered by Wali and Wright (2016) on British university students posits the significant influence of handling student complaints on student loyalty. The same results could be found in previous works by Abubakar and Mohd Mohktar (2015) and Manzuma-Ndaaba et al. (2018). They found that handling student complaints by universities in Malaysia was a crucial factor in student loyalty. By contrast, Chandra et al. (2019) were unable to prove that the handling of student complaints had a positive influence on student loyalty.

Zeithaml et al. (1996) mentioned that satisfaction with the value of the product or service is the key driver of customer loyalty. A study conducted by Alves and Raposo (2010) involving students from Portugal managed to confirm a positive and significant link between student satisfaction and student loyalty. Past work by Annamdevula and Bellamkonda (2016) also demonstrated the positive effect of student satisfaction on student loyalty. They found that student satisfaction at universities in India strongly facilitated student loyalty. Similar results were found in studies administered by Ali et al. (2016), Manzuma-Ndaaba et al. (2018) and Chandra et al. (2019). They found that student satisfaction had a positive and significant influence on student loyalty among university students in Malaysia and Riau respectively. Based on the findings (H3, H4 and H5), higher education providers should realize that the cost of attracting new customers is five times more than retaining existing customers, therefore they should have a proper service recovery strategy to minimize the number of dissatisfied customers. The outcomes of better service recovery are a critical factor in a company’s success, it lowers the switch rate and is a source of competitive advantage (Hoffman et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2015; Komunda & Osarenkhoe, 2012; Makanyeza & Chikazhe, 2017; Santouridis & Trivellas, 2010).

Conclusions

The first goal of this study was to investigate the impact of relationship marketing and the handling of student complaints on student satisfaction. The results confirmed that these constructs have a significant influence on student satisfaction. In addition, this present study also measured the influence of relationship marketing, the handling of student complaints and student satisfaction on student loyalty. The findings revealed that all three constructs have a positive relationship with student loyalty. The findings will help Uniten to maintain and further improve its service recovery strategy by managing relationship marketing and handling student complaints. These two constructs are critical and strongly influence student satisfaction and loyalty. This study only used one university to test the hypotheses, therefore, a future study could extend this study to other higher education providers. In addition, a future study could consider adding constructs like dimensions of service quality and relationship commitment to the framework.

References

- Abubakar, M. M., & Mokhtar, S. S. M. (2015). Relationship marketing, long-term orientation and customer loyalty in higher education. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(4), 466-474.

- Aka, D. O., Kehinde, O. J., & Ogunnaike, O. O. (2016). Relationship marketing and customer satisfaction: A conceptual perspective. Binus Business Review, 7(2), 185-190.

- Alemu, A. M., & Cordier, J. (2017). Factors influencing international student satisfaction in Korean universities. International Journal of Educational Development, 57(2017), 54-64.

- Ali, F., Zhou, Y., Hussain, K., Nair, P. K., & Ragavan, N. A. (2016). Does higher education service quality effect student satisfaction, image and loyalty? A study of international students in Malaysian public universities. Quality Assurance in Education, 24(1), 70-94.

- Alrubaiee, L., & Al-Nazer, N. (2010). Investigate the impact of relationship marketing orientation on customer loyalty: The customer’s perspective. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 2(1), 155-173.

- Alves, H., & Raposo, M. (2010). The influence of university image on student behaviour. International Journal of Educational Management, 24(1), 73-85.

- Annamdevula, S., & Bellamkonda, R. S. (2016). Effect of student perceived service quality on student satisfaction, loyalty and motivation in Indian universities: Development of HiEduQual. Journal of Modelling in Management, 11(2), 488-517.

- Chahal, H., & Devi, P. (2015). Consumer attitude towards service failure and recovery in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 23(1), 67-85.

- Chandra, T., Hafni, L., Chandra, S., Purwati, A. A., & Chandra, J. (2019). The influence of service quality, university image on student satisfaction and student loyalty. Benchmarking: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-07-2018-0212

- Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. Esposito Vinci, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (655-690). Springer.

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (295-336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic.

- Dabholkar, P. A., & Spaid, B. I. (2012). Service failure and recovery in using technology based self-service: Effects on user attributions and satisfaction. The Service Industries Journal, 32(9), 1415-1432.

- Department of Higher Education (2017). Ministry of Higher Education. http://jpt.mohe.gov.my/senarai-daftar-ipts

- Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2006). Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. British Journal of Management, 17(4), 263-282.

- Duarte, P., & Raposo, M. (2010). A PLS model to study brand preference: An application to the mobile phone market. In V. Esposito Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares (449-485). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Filip, A. (2013). Complaint management: A customer satisfaction learning process. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 271-275.

- Firdaus, A., & Kanyan, A. (2014). Managing relationship marketing in the food service industry. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 32(3), 293-310.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Haile, S. (2019). The determinant of service quality measurement in the case of Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. Journal of Economics, Management and Trade, 22(6), 1-19.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis (6th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Harman, H. H. (1967). Modern Factor Analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hart, D., & Nigel, C. (2011). International student complaint behaviour: understanding how East-Asian business and management students respond to dissatisfaction during their university experience. International Journal of Education Management, 9(4), 57-66.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135.

- Hoffman, K. D., Kelley, S. W., & Rota, H. M. (2016). Retrospective: Tracking service failures and employee recovery efforts. Journal of Services Marketing, 30(1), 7-10.

- Hornik, J., Satchi, R. S., Cesareo, L., & Pastore, A. (2015). Information dissemination via electronic word-of-mouth: Good news travels fast, bad news travels faster. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 273-280.

- Ibidunni, O. S. (2012). Marketing management: Practical perspectives. Lagos: Concept Publications.

- Istanbulluoglu, D. (2017). Complaint handling on social media: The impact of multiple response. Computers in Human Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.016

- Khoo, S., Ha, H., & McGregor, S. L. T. (2015). Service quality and student/customer satisfaction in the private tertiary education sector in Singapore. Journal of Service Management, 26(2), 430-444.

- Kim, M., Vogt, C. A., & Knutson, B. (2015). Relationships among customer satisfaction, delight, and loyalty in the hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 39(2), 170-197.

- Kim, N., & Ulgado, F. M. (2012). The effect of on-the-spot versus delayed compensation: the moderating role of failure severity. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(3), 158-167.

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Komunda, M., & Osarenkhoe, A. (2012). Remedy or cure for service failure?: Effects of service recovery on customer satisfaction and loyalty. Business Process Management Journal, 18(1), 82-103.

- Kumari Adikaram, C. N., Khatibi, A., & Ab. Yajid, M. S. (2016). Customer satisfaction: A study on private higher education institutions in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Arts and Commerce, 5(2), 69-95.

- Lewis, B. R., & Spyrakopoulas, S. (2001). Service failures and recovery in retail banking: The customer’s perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 19(1), 37-47.

- Makanyeza, C., & Chikazhe, L. (2017). Mediators of the relationship between service quality and customer loyalty. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(6), 997-1017.

- Manzuma-Ndaaba, N. M., Harada, Y., Nordin, N., Abdullateef, O., & Romle, A. R. (2018). Application of social exchange theory on relationship marketing dynamism from higher education service destination loyalty perspective. Management Science Letters, 8, 1077-1096.

- Mapunda, M. A., & Mramba, N. R. (2018). Institutions in Tanzania-lessons from the college of business education. Business Education Journal, II(I), 1-7.

- Mazhari, M. Y., Madahi, A., & Sukati, M. (2012). The effect of relationship marketing on costumers’ loyalty in Iran Sanandaj city banks. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(15), 81-87.

- Moyo, A., & Ngwenya, S. N. (2018). Service quality determinants at Zimbabwean state universities. Quality Assurance in Education, 26(3), 374-390.

- Nauroozi, S. E., & Moghadam, S. K. (2015). The study of relationship marketing with customer satisfaction and loyalty. Internationla Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences, 2(2), 96-101.

- Ndubisi, N. O. (2007). Relationship marketing and customer loyalty. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 25(1), 98-106.

- Ndubisi, N. O., & Nataraajan, R. (2018). Customer satisfaction, confucian dynamism, and long-term oriented marketing relationship: A threefold empirical analysis. Psychology and Marketing, 35(2). doi: 10.1002/mar.21100

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Ogunnaike, O. O., Sholarin, A., Salau, O., & Borishade, T. T (2014). Evaluation of customer service and retention: A comparative analysis of telecommunication service providers. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 3(8), 273-288.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879-903.

- Santouridis, I., & Trivellas, P. (2010). Investigating the impact of service quality and customer satisfaction on customer loyalty in mobile telephony in Greece. The TQM Journal, 22(3), 330-343.

- Teo, T. S. H., Srivastava, S. C., & Jiang, J. Y. (2008). Trust and electronic government success: An empirical study. Journal of Management Information Systems, 25(3), 99-132.

- Voss, R., Gruber, T., & Reppel, A. (2010). Which classroom service encounters make students happy or unhappy? International Journal of Education Management, 24(7), 615-636.

- Wali, A. F., & Wright, L. T. (2016). Customer relationship management and service quality: Influences in higher education. Journal of Customer Bahaviour, 15(1), 67-79.

- Wong, H., Wong, R., & Leung, S. (2018). Relationship marketing in tertiaty education: Empirical study of relationship commitment and student loyalty in Hong Kong. International Business Research, 11(2), 2015-221.

- Wong, K. K. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin, 24(1), 1-32.

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60, 31-46.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 December 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-099-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

100

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-905

Subjects

Multi-disciplinary, accounting, finance, economics, business, management, marketing, entrepreneurship, social studies

Cite this article as:

Zahari, A. R., Esa, E., & Surbaini, K. N. (2020). Effect Of Marketing And Handling Student Complaints Onstudent Satisfaction And Loyalty. In N. S. Othman, A. H. B. Jaaffar, N. H. B. Harun, S. B. Buniamin, N. E. A. B. Mohamad, I. B. M. Ali, N. H. B. A. Razali, & S. L. B. M. Hashim (Eds.), Driving Sustainability through Business-Technology Synergy, vol 100. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 670-680). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.12.05.73