Abstract

Today's intense global competition conditions have led the local and small markets to leave their places to bigger and more developed markets. In addition to this, businesses have to make different strategic decisions in order to survive and profit. One of the ways for firms that fail to increase their brand equity with their own resources is to go through a merger and / or acquisition transaction with a different firm. In this way, firms which benefit from each other's strengths are striving to exist, differentiate and grow in an international competitive environment with the impact of globalization. The main purpose of this research is the effect of market and brand performance on competitiveness in the context of mergers and acquisitions transactions which are done in Turkey. The universe of the study is the firms that have performed mergers and acquisitions transactions in Turkey. Between 2010 and 2017, 2287 firms that have performed mergers and acquisitions transactions constitute the sample framework of the study and the sample size is limited to 243 enterprises. As a result of the analyses, the current status of the effect of brand performance on competitiveness according to our findings has been evaluated, and new proposals regarding this topic have been made for future researches.

Keywords: Mergeracquisitionbrand performancemarket performancecompetitiveness

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions, brand, brand value, brand performance, and competitiveness are factors which started to be intensively used especially in Europe and the USA in the 1980s and have been seen as important issues by firms (Baydaş, 2007). Concepts such as brand performance, market performance and brand value are receiving increasing attention in the marketing literature from the beginning of the 1990s (Vazquez, Del Rio, & Iglesias, 2002) with academics interested in these subjects and their studies (Kocaman & Güngör, 2012). In addition, thanks to the manufacturers' position on the market and the impact on their financial performance, it can be seen that brands are a financial value that can be expressed in greater numbers than the tangible assets (Franzen, 2002). Competitive firms that want to succeed in the global market are now turning to significant branding with higher quality products and production. With the life spans of products getting shorter, product-oriented competition strategies have been replaced by brand and market / firm oriented strategies, and as a result of these changes branding, market performance and brand performance have become more important firm strategies (Bridson & Evans, 2004; Urde, 1994). Businesses are generally engaged in mergers and acquisitions with the aim of enhancing their competitiveness in growth, empowerment, internationalization, and consequently competitiveness with other businesses in both local and global markets. In this study, the effects of brand performance and market performance on competitiveness were investigated as a result of mergers and / or acquisitions performed by the companies at the national or international level. In this respect, the concepts of brand, brand performance and market performance, competition in local and global markets, mergers and acquisitions activities and effects of firms at the national and international level are examined. According to the findings of this research, it can be said that those findings are the ones that will help both the academics and the professionals working in the sector.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Brand, Brand Performance and Market Performance

In the 18th century, branding gained a new value with the replacement of the trademark names with the names of famous people or places.

In the 19th century, brands began to be used to emphasize the perceived value of the product, and in the 20th century, issues such as how to make and sustain brands became important (Farquhar, 1989; Motemani & Shahrokhi, 1998).

According to the American Marketing Association (AMA), "A brand is a name, a term, a mark, a symbol or a design that aims to identify and separate products and services from a dealer or a group of sellers." (https://www.ama.org). The brand gives the product a distinctive superiority over its competitors by identifying it. At the same time, it increases the competitive power and provides an abstract advantage. Firms give the products competitive advantage in markets with brands (Tek & Özgül, 2005). When evaluated in the financial context, the brand gained a saleable value attribute (Uztuğ, 2003).

Competitiveness

It is difficult to say in the literature that there is a complete definition of the concept of competitiveness. The concept of competitiveness is defined in different ways depending on the area and the criteria covered. It can be examined and defined in macro and micro dimensions as well as in the fields of country, industry and firm. According to Krugman (1994), competitiveness is a concept that has to be addressed at the firm level and has the same meaning as productivity at the country level, which is why it is not very meaningful. Firms compete with each other in such a way that the loss of one is the gain of the other, but according to the law of comparative advantage, they can all gain together in the case of the countries. Thus, according to Krugman (1994), the concept of competitiveness has different meanings for firms and countries. The concept of competitiveness can be examined at three levels. These levels are:

Mergers and Acquisitions

Merging between firms, which is considered to have begun in the 1890s, is divided into five major turning points. These periods, which are called merger waves can be listed from the 1890s, the 1920s, the 1960s, the 1980s and the 1990s to the present day (Gregoriou & Renneboog, 2007). It is seen that this phenomenon appeared in the USA when the historical development of mergers in both national and international markets was examined. In Turkey, merging between firms has appeared with increasing concentration of economic structure in the 1980s. The first merger transaction in Turkey has emerged in the banking sector (Sarıca, 2008). Mergers and acquisitions, which are frequently seen in Europe, are preferred with the aim of adapting to changing economic conditions, globalization and increasing competitive conditions. The main driving force in between European firms is external competition, particularly competition with US-owned firms (Lipczynski & Wilson, 2001; Scherer & Ross, 1990). It is referred to as a merger of two or more independent firms as an independent new entity under a new name, collecting all assets and capabilities under the same roof, terminating their former identity and legal entity (Ülgen & Mirze, 2013). Mergers are referred to as "acquisitions" if the merger takes place through takeover. Acquisitions take place if a firm takes over all the assets and liabilities of the target firm, and if the legal entity of the acquiring firm or acquired the firm cease to exist (Çelik, 1999). In mergers, more than one independent firm brings together all the assets and capabilities of the current situation by ending the old identity and legal entities and is operating as an independent new firm under a new name. At this point, the goal is to achieve a stronger position by equally combining the two firms' powers, thus maintaining their assets, providing competitive advantage and growing. Acquisitions take place if a firm mostly or completely takes over the other firm’s shares, therefore taking control over it (Ülgen & Mirze, 2013). The acquisition process is regarded as the purchase of a small-scale firm by a large-scale firm. Large-scale firm buy small businesses to enter different markets or to increase the variety of products. Thus, a large-scale firm can present new products to the market with less cost or operate on different markets. In the case of purchases taking place between firms of different sizes, the company loses its legal and economic independence (Phillips & Zhdanov, 2012). The difference between mergers and acquisitions arises from legal grounds rather than economic aspects of transactions. In other words, merger and acquisition are two different concepts, but serve the same purpose. In this context, authors explain the causes of merger and acquisition transactions; globalization, growth, synergy, diversity, tax advantages and psychological factors. According to Mueller (1989) the main motivation for the B&S firms is to reduce the market power, efficiency gains, financial gains and risk gained by merging to a minimum by the synergy achieved (p.2). However, the structure of the industry and the impact on competition may not always be positive for these gains, which are considered earnings for the firm.

The Effect of Merger and Acquisition on Brand Performance

Brands play an important role in helping firms increase their competitiveness and achieve growth and profitability. The realization of this potential of brands creates a key point in the creation of business strategies that target sustainable competitive advantage (Urde, 1994). Lee, Lee, & Wu, (2011) examined the relationship between two brand images variables and the dimensions of brand value after mergers and acquisitions. The firm that performs the acquisitions from the other firm which is used in the research has the weak brand image and the target business has strong brand image. This study tries to explain how two separate businesses with weak and strong brand images influence the brand value of the target business. The findings show that a firm with a negative brand image improves the consumer-based brand value significantly by acquiring a brand with a strong image. In other words, by acquiring a better brand, businesses improve the existing image of the brand.

The Effect of Mergers and Acquisitions on Market Performance

As a result of Sorensen’s (2000) study, it is seen that the firms that make acquirements are more profitable than both the target firms and firms which do not merge. Vanitha and Selvam (2007) reviewed 17 firms that engaged in mergers and acquisitions in India between 2000-2002. They stated that after merging, there was an increase in the profitability of the firms, a positive change in the debt payment power and a better liquidity structure. There are studies showing that mergers and acquisitions have a positive effect on market performance, as well as studies showing that they do not reduce profitability or affect profitability. Pazarskis, Vogiatzogloy, Christodoulou, & Drogalas (2006) analyzed 15 mergers and acquisitions in Greece between 1998 and 2002 and found strong evidence that corporate profitability was reduced due to mergers and acquisitions. The vast majority of studies of firms, marketing and strategic management literature assume that there is a direct positive correlation between competitive advantage and market performance. Customers evaluate advantageous offers and companies gain competitive advantage when they make acquisitions. This, in turn, increases the manufacturer's market performance (Kaleka & Morgan, 2017).

Research Method

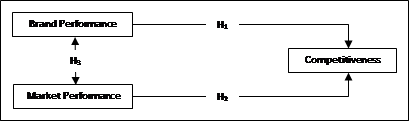

This study aims to investigate the effect of brand and market performance on competitiveness in the context of mergers and acquisitions. The secondary purpose of the study is to investigate the relationship between brand and market performance. Assessing the current situation of companies which carried out merger and acquisition transactions in Turkey in the context of brand performance, market performance and competitiveness is another aim of the present study.

Sample and Data Collection

The universe of this study is the firms which carried out mergers and acquisitions and the sample frame is the firms which carried out mergers and acquisitions between 2010 and 2017. The list of these companies obtained from the reports of mergers and acquisitions which were prepared and published by Ernst and Young Turkey between 2010 and 2017. It can be seen in the reports that total number of merger and acquisition transactions is 2287 (Ernst & Young 2010-2017 Mergers & Acquisitions Report). A total population sampling method was employed to gather data from the companies. Contact information for all listed companies were gathered and each were contacted. The survey could be applied to 243 out of 2287 businesses. The sample of the study consisted of 243 firms. Computer aided telephone interview (CATI) method was used to gather data. The CATI method was preferred because of the fact that the businesses included in the sample frame were located in different regions, and obstacles such as time constraints which stem from managers intensive work tempo could be reduced by this method (Burns & Bush, 2015). The respondents comprise of managers who work at various stages of the companies. In the case of any item that was not understood by the respondent, these items were immediately explained in detail by the interviewer and the survey was continued. Explaining the items that were not understood and being in contact during the survey process ensured the completion of the questionnaires thoroughly. All 243 completed surveys were subjected to analyze. The data was collected between 31th of January and 15th of March 2018.

Research Model

In order to measure the effect of brand performance and market performance on competitiveness, brand and market performance were used as independent variables and competitiveness was used as dependent variable. Brand performance was measured by eight items which were adapted from Wong and Merrilees (2008); Hirvonen and Laukkanen (2014). Market performance was measured by six items which were adapted from Çalık et al., (2013). Competitiveness was measured by fourteen items which were adapted from Lii and Kuo (2016).

The questionnaire which was used in the research consists of 36 questions and two parts. Of these questions, 28 items are five-likert types, 8 items are multiple-choice. All items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1: Strongly disagree, …, 5: Strongly agree).

Findings

The demographic characteristics of respondents can be seen in the Table

27 % of the merger transactions are national mergers while 73 % are international mergers. 59 % of the acquisition transactions are national acquisitions while 41 % are international acquisition. Considering the years in which transactions were carried out, it can be seen that the maximum amount of transaction was performed in 2010 and 2013. When the level of internationalization of companies is examined, results reveal that 30.9 % of the companies are national, 53.9% are international and 15.2% are global companies. While 32.5% of the businesses had been operating for over 21 years, 33 % employ 250 people or more.

Table

Table

Table

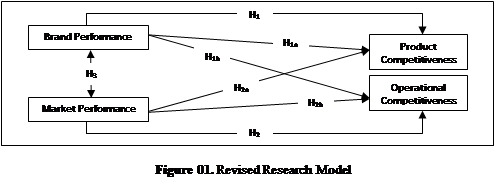

All of the scales used in the research were subjected to factor analysis. Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin values were 0,929, 0,878 and 0,914 and Bartlett Test significant level was 0,000, so that the sample was both adequate and sufficient for the factor analysis. According to factor analyses, brand and market performance were singled out in one factor group, competitiveness was singled out into two factor groups. These factor groups were named as

In order to predict the effect of brand performance and market performance on competitiveness and competitiveness’ dimensions regression analyses were performed.

H1 showed that brand performance had a significant and positive effect on competitiveness (β: 0,491 - sig: 0,000) and so H1 was supported. H1a revealed that brand performance had a positive effect on product competitiveness (β: 0,450 - sig: 0,000) and so H1a was approved. H1b demonstrated that brand performance had a positive effect on operational competitiveness (β: 0,432 - sig: 0,000) therefore H1b was supported. H2 showed that market performance had a significant and positive effect on competitiveness (β: 0,511 - sig: 0,000) as well as H2a proved that market performance had a significant and positive effect on competitiveness (β: 0,408 - sig: 0,000) and so H2a was supported. Lastly, H2b confirmed that market performance had a significant and positive effect on competitiveness (β: 0,515 - sig: 0,000) and so H2b was accepted.

Correlation and regression analyses were employed to test the hypothesis. It can be seen in the Table

Conclusion and Discussions

This paper aims to investigate the effect of brand performance and market performance on competitiveness in the context of mergers and acquisitions. The results of the correlation analyses showed that there is a positive relationships between brand performance, market performance, and competitiveness. It is possible to say that the strongest relationship has occurred between brand performance and market performance. To gain desired market share and performance in the long term can be achieved by investing in branding activities. On the other hand increasing market share and performance will promote branding activities and brand performance. Customers have been in search of well-known goods and services. Branding is one of the ways to reinforce the reputation of a firm and so investing in branding will help to increase market performance and brand performance mutually and strategically.

Dimensions of competitiveness emerged in this study have been observed to be

In conclusion, businesses are in search of competitiveness and mergers and acquisitions are alternative ways to gain competitiveness. On the other hand brand performance and market performance levels are the determinant of a firm’s financial and non-financial performance. It can be said that increasing brand and market performance by merger and acquisition transactions can also increase competitiveness. Mergers and acquisitions which are strategically planned and possible outcomes of which are predicted can be effective on achieving successful firm performance.

As with every study, this paper has its own limitations. The findings can be generalized only for firms which carried out mergers and acquisitions. Further research may reveal other dimensions of competitiveness and their relations with other independent variables by using another comprehensive competitiveness scale. Investigating export performance and strategic results of merger and acquisition transactions can be studied by scholars in the future research.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Marmara University Scientific Research Projects Commission within the scope of the project SOS-A-111017-0589.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. New York: The Free Press.

- Akman, G., Özkan, C., & Eriş, H. (2008). Strateji odaklılık ve firma stratejilerinin firma performansına etkisinin analizi. İstanbul Ticaret Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi, 7(13), 93-116.

- American Marketing Association (AMA) (1 April 2018). Retrieved from: (https://www.ama.org).

- Baldauf, A., Cravens, K. S., & Binder, G. (2003). Performance consequences of brand equity management: evidence from organizations in the value chain. Journal of product & brand management, 12(4), 220-236.

- Baydaş, A. (2007). Pazarlama açısından markanın finansal değeri ve dış ticaret işletmelerinde bir uygulama. Türk Dünyası Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, (42), 127-150.

- Bridson, K., & Evans, J. (2004). The secret to a fashion advantage is brand orientation. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 32(8), 403-411.

- Burns, A. C., Bush, R. F., Orel, F. D. (trans. ed.) (2015). Pazarlama Araştırması. Ankara: Nobel Yayın.

- Çalik, M., Altunişik, R., & Sütütemiz, N. (2013). Bütünleşik pazarlama iletişimi, marka performansı ve pazar performansı ilişkisinin incelenmesi. Uluslararası Yönetim İktisat ve İşletme Dergisi, 9(19), 137-161.

- Çelik, O. (1999). Şirket birleşmeleri ve birleşmelerde şirket deǧerlemesi. Turhan Kitabevi.

- Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81-93.

- Cockburn, J., Siggel, E., Coulibaly, M., & Vézina, S. (1999). Measuring competitiveness and its sources: the case of Mali's manufacturing sector. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 20(3), 491-519.

- dos Reis Velloso, J. P. (1990). International competitiveness and the creation of an enabling environment. International Competitiveness, 29.

- Durmuş, B., Yurtkoru, E.S. & Çinko, M. (2011). Sosyal Bilimlerde SPSS’le Veri Analizi, 4. Edition, İstanbul: Beta Yayınları.

- Ernst &Young Türkiye Merger and Acquisition Report 2010 (17 January 2018). Retrived from: https://www.google.com/search?q=Ernst%26Young+T%C3%BCrkiye+Merger+and+Acquisition+Report+2010&oq=Ernst%26Young+T%C3%BCrkiye+Merger+and+Acquisition+Report+2010&aqs=chrome..69i57.1688j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

- Ernst &Young Türkiye Merger and Acquisition Report 2011-2016 (17 January 2018). Retrieved from: https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/MA_2016_Raporu_ENG/%24FILE/EY_M&A_Report_2016_ENG.pdf

- Ernst &Young Türkiye Merger and Acquisition Report 2017 (17 January 2018). Retrieved from: https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/MA_2016_Raporu_ENG/%24FILE/EY_M&A_Report_2016_ENG.pdf

- Fagerberg, J. (1995). User-producer interaction, learning and comparative advantage. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19, 39-51.

- Farquhar, P.H. (1989). Managing brand equity. Marketing Research, 1, 24–33.

- Franzen, G. Alım, F. (trans. ed.) (2002). Reklamın Marka Değerine Etkisi. MediaCat Kitapları.

- Gregoriou, G. N., & Renneboog, L. (2007). Understanding mergers and acquisitions: activity since 1990. International Mergers and Acquisitions Activity Since 1990. Recent Research and Quantitative Analysis, 1.

- Hansen, G. S., & Wernerfelt, B. (1989). Determinants of firm performance: The relative importance of economic and organizational factors. Strategic Management Journal, 10(5), 399-411.

- Hatsopoulos, G. N., Krugman, P. R., & Summers, L. H. (1988). US competitiveness: Beyond the trade deficit. Science, 241(4863), 299-307.

- Hirvonen, S., & Laukkanen, T. (2014). Brand Orientation in Small Firms: An Empirical Test of the Impact on Brand Performance. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 22(1), 41-58.

- Hounie, A., Pittaluya, L, Porcile, G. ve Scatolin, F. (1999). Eclac and the new growth theories. Cepal Review. No 68.

- Jenkins, R. (1998). Environmental regulation and international competitiveness: a review of literature and some European evidence. United Nations University, Institute of Technologies.

- Kaleka, A., & Morgan, N. A. (2017). Which Competitive Advantage (s)? Competitive Advantage–Market Performance Relationships in International Markets. Journal of International Marketing, 25(4), 25-49.

- Kapferer, J. N. K. (2012). The new strategic brand management (5th ed.).London, UK: Kogan Page.

- Kocaman, S., & Güngör, İ. (2012). Destinasyonlarda Müşteri Temelli Marka Değerinin Ölçülmesi ve Marka Değeri Boyutlarının Genel Marka Değeri Üzerindeki Etkileri: Alanya Destinasyonu Örneği. Alanya İşletme Fakültesi Dergisi, 4(3), 143-161.

- Krugman, P. (1994), Competitiveness: a dangerous obsession, Foreign Affairs, 73(2), 28-46.

- Kumar, N., Stern, L. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1993). Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1633-1651.

- Lebas, M., & Euske, K. (2002). A conceptual and operational delineation of performance. Business performance measurement: Theory and practice, 65-79.

- Lee, H. M., Lee, C. C., & Wu, C. C. (2011). Brand image strategy affects brand equity after M&A. European Journal of Marketing, 45(7/8), 1091-1111.

- Lii, P., & Kuo, F. I. (2016). Innovation-oriented supply chain integration for combined competitiveness and firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 174, 142-155.

- Lipczynski, J., & Wilson, J. (2001). Industrial Organization: An Analysis of Competitive Market, New York: Pearson Education Limited, & Prentice Hall (Financial Times).

- Marangoz, M., & Biber, L. (2007). İşletmelerin pazar performansi ile insan kaynakları uygulamaları arasındaki ilişkinin araştırılmasına yönelik bir çalışma. Doğuş Üniversitesi Dergisi, 8 (2) 2007, 202-217

- Markusen, J. R. (1992). Productivity, competitiveness, trade performance and real income: The nexus among four concepts. Economic Council of Canada.

- McFetridge, D. (1995), Competitiveness: Concepts and measures. Occasional Paper N°5, Industry, Canada.

- Motameni, R., & Shahrokhi, M. (1998). Brand equity valuation: a global perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 7(4), 275-290.

- Mueller, D. C. (1989). Mergers: Causes, effects and policies. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 7(1), 1-10.

- Neely, A. (Ed.). (2002). Business Performance Measurement: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511753695

- O’Cass, A., & Ngo, L. (2009). Achieving customer satisfaction via market orientation, brand orientation, and customer empowerment: Evidence from Australia Available at: http://anzmac.info/conference/conference-proceedings.

- Pazarskis, M., Vogiatzogloy, M., Christodoulou, P., & Drogalas, G. (2006). Exploring the improvement of corporate performance after mergers–the case of Greece. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 6(22), 184-192.

- Phillips, G. M., & Zhdanov, A. (2013). R&D and the Incentives from Merger and Acquisition Activity. The Review of Financial Studies, 26(1), 34-78.

- Porter, M. E. (1991). Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 12(2), 95-117.

- Porter, M. E. (1998). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: The Free Press.

- President’s Commission on Industrial Competitiveness. (1992). Report of The President’s Commission on International Competitiveness. Washington D.C.

- Sarıca, S. (2008.) ABD, AB ve Türkiye’nin firma birleşmelerine yaklaşımı. Ekonomik ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, 4(1), 51-82.

- Scherer, F.M. & Ross, D. (1990), Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance, 3rd ed., Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

- Sorensen, D. E. (2000). Characteristics of merging firms. Journal of Economics and Business, 52(5), 423-433.

- Styles, C. (1998). Export performance measures in Australia and the United Kingdom. Journal of International Marketing, 6(3), 12-36.

- Tek, Ö. B., & Özgül, E. (2005). Modern pazarlama ilkeleri. İzmir: Birleşik Matbaacılık, 749.

- Ülgen H., & Mirze K. (2013). İşletmelerde Stratejik Yönetim, 8. Baskı, İstanbul, Beta Yayınları.

- Ulusoy, G., Özgür, A., & Taner, D. (1997). Rekabet Stratejileri ve En İyi Uygulamalar: Türk Elektronik Sektörü. Tüsiad, Istanbul.

- Urde, M. (1994). Brand orientation–a strategy for survival. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 11(3), 18-32.

- Uztuğ, F. (2003). Markan kadar konuş. MediaCat Kitapları, İstanbul.

- Vanitha, S., & Selvam, M. (2007). Financial performance of Indian manufacturing companies during pre and post-merger. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 12, 7-35.

- Vazquez, R., Del Rio, A. B., & Iglesias, V. (2002). Consumer-based brand equity: development and validation of a measurement instrument. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(1-2), 27-48.

- Volonté, C. & Gantenbein, P. (2016). Directors' human capital, firm strategy, and firm performance. Journal of Management & Governance. 20(1), 115-145. ISSN 1385-3457. eISSN 1572-963X. Available under: doi: 10.1007/s10997-014-9304-y

- Wong, H. Y., & Merrilees, B. (2007). Closing the marketing strategy to performance gap: the role of brand orientation. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 15(5), 387-402.

- World Economic Forum (WEF). (1989). The global competitiveness report. World Economic Forum.

- Yin Wong, H., & Merrilees, B. (2008). The performance benefits of being brand-orientated. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 17(6), 372-383.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-053-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

54

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-884

Subjects

Business, Innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Erdil, T. S., Aydoğan, S., Ayar, B., Güvendik, Ö., Diler, S., & Gusinac, K. (2019). Effect Of Brand And Market Performance On Competitiveness In Mergers And Acquisitions. In M. Özşahin, & T. Hıdırlar (Eds.), New Challenges in Leadership and Technology Management, vol 54. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 44-58). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.02.5