Abstract

The article is devoted to advanced Master Degree students’ extrinsic and intrinsic motivation when learning a foreign language within Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) settings. The author analyzes students’ motivation and anxiety for a task from the point of its design, the dopamine and the opioid systems, the input-output aspect, heuristic and algorithmic procedures, and autonomy provided. Considering scientific publications reviewed, the author demonstrates a novel idea for Content and Language Integrated Learning – professionally-oriented incident-based tasks. An example of an incident-based task for Master Degree students majoring in management is given, its processing plan is provided. Being based on the same key principles, the novel tasks proposed are relevant to Content and Language Integrated Learning. Analysis of the results of the pedagogical experiments conducted to check the hypothesis of the incident-based tasks efficiency is given and discussed. The findings show that incident-based tasks stimulate students’ anxiety and motivation in accordance with the dopamine and the opioid systems effects. The author concludes that the incident-based tasks not only stimulate experienced students’ motivation and anxiety, but also contribute to their personal qualities and professional skills development. The idea behind enables Incident-based tasks implementation when working with experienced students of different majors.

Keywords: CLILforeign language competenceinternet-basedprofessionally-orientedprofessional discourse

Introduction

According to current Russian Federal Educational Standards, future Masters of Sciences are to be ready for intercultural communication and be competent enough to solve professional problems in a foreign language of their choice (Federal Educational Standard, 2015). This requirement calls for innovation in the sphere of education to help students simultaneously master professional content and level of language proficiency. Therefore, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) becomes relevant to the educational context concerned (Dashkina & Fyodorova, 2017; Kogan, Khalyapina, & Popova, 2017).

Requiring applied knowledge, CLIL is a key to a more advanced and sophisticated level of expertise. Even setting greater challenges to teachers by its purpose-designed tasks, CLIL, nevertheless, is becoming more and more popular, since it is based on a “two-for-the-price-of-one” idea (Bruton, 2013, p. 588), which is especially relevant within the nowadays limited number of in-class hours.

For students a CLIL class is definitely more complicated than any traditional learning, because it requires cognitive flexibility, involvement and constant focus. According to researchers, success of CLIL settings is dependent on such students’ qualities, as “prior achievements, general cognitive abilities, motivation” (Dallinger, Johnmann, Hollm, & Fiege, 2016, p. 23). We suppose that those students, who have the characteristics mentioned, are not only “able to deal with more difficult tasks” (Roussel, Joulia, Tricot, & Sweller, 2017, p. 3), but can become even more motivated and skilled by the cognitive load they are exposed to.

Problem Statement

Motivation is a key component for language learning especially when it is a CLIL class for experienced Master’s students with high level of language proficiency and expertise in the field of their major. Even considering the fact that CLIL replaces students’ bad attitude to any of the disciplines included in a CLIL setting with “a feel good attitude” (Chostelidou & Griva, 2014, p. 2170) motivation and anxiety factors should nevertheless be taken into special account.

Investigations prove that there are two types of motivation –intrinsic and extrinsic or integrative and instrumental depending on the origins (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010). This raises such questions as: what does the type of motivation depend on? Which type is preferable? What is a necessary prerequisite for either extrinsic or intrinsic motivation?

For example, decades ago when computers and the Internet were less widespread and rarely used in education, a computer-based task stimulated motivation. Nowadays, computers and the Internet are considered ordinary tools and cannot boost students’ motivation and anxiety (Almazova & Kogan, 2014). Thus, in terms of an internet-based task more attention should be paid to the task itself – its major idea, content included and design. To accomplish this, the nature of motivation is to be analyzed and considered.

Research Questions

The task design theories

Daniel Pink analyzed types of work people do and the way they accomplish tasks. He found out that nowadays 70% of developing countries populations prefer working heuristically – doing work without set procedures. He concluded that in terms of heuristic work people are motivated intrinsically by the work itself. In this case they don’t need additional algorithm, punishments, control and rewards that are typical for algorithmic work and extrinsic motivation (Pink, 2009). Therefore, we can suppose that a task can be a reward itself. Thus, in order to motivate students intrinsically the only thing a CLIL teacher should do is to create a proper task, which is certainly a hard challenge to face.

It is believed that when trying to influence someone’s actions or behaviour, it is rational to provide autonomy (Fryer & Bovee, 2016) or/and suggest types or forms of work that are interesting for a person (Weinschenk, 2011) depending on his or her aspirations. Thus, the task and materials it is based on should relate to students emotional intelligence and stimulate anxiety and motivation by giving a chance for the students to demonstrate their knowledge. In this regard, professionally-oriented CLIL tasks can motivate students naturally by containing professionally-oriented content and requiring professionally-oriented actions (applying knowledge, experience, theory, etc.).

The design and idea of a task can be better understood and evaluated with the help of the dopamine system. Dopamine has always been considered to be responsible for “the pleasure system of the brain” however, according to scientists, dopamine is closely linked to anxiety (Weinschenk, 2011, p. 121). Researchers state that there are two systems responsible for our actions – the dopamine system and the opioid system. The dopamine system is crucial for a number of brain functions, for example: thinking, mood, motivation, wanting, seeking, reward, whereas the opioid system is related to positive feelings experienced when the goal has been achieved (Berridge & Robinson, 1998).

The research analyzed proves that the dopamine system has greater impact on a person due to its long-lasting effect, as dopamine is created during goal-oriented search and willingness to get reward, not necessarily a monetary one or an excellent mark; this reward can be, for instance, some data one has been looking for. It is believed that in the case of information search the creation of dopamine is also stimulated by the unpredictability. That is why, according to neuroscientists, to set off students’ dopamine system, it is recommended to create short texts and messages that do not contain all the data needed to understand the whole picture, because this situation requires additional search and gives a cue that something is going to happen (Weinschenk, 2011). The amount of data that doesn’t satisfy the desire for the information stimulates the anticipation of some actions or rewards and therefore stimulates the dopamine system. Considering everything mentioned a proper task to motivate students:

can be accomplished heuristically and shouldn’t necessarily have a set algorithm of actions or a strict order;

should be interesting for the target audience;

should stimulate the dopamine system by requiring additional search;

should stimulate the opioid system by satisfying the search carried out.

The language comprehensible input

According to CLIL researchers, when designing a task it’s important to consider “how the students meet the content”, “what they do while learning it” and later “how understanding is expressed” (Coyle et. al, 2010, p. 87). One cannot argue that the Internet is the most valuable source of information, as it contains data relevant to different issues, either current or old ones. Having found the data needed, the teacher faces the challenge of selecting, combining and modifying it to expose his or her students to the topic of the study. When working with advanced learners, a CLIL teacher is to consider students’ knowledge and experience to mediate their engagement, in other words, the so-called input-output aspect.

On one hand, it’s worth mentioning Swain’s idea about the importance of the language competence level students demonstrate, as it shows their understanding (Swain, 1996), but, on the other hand, since Master Degree students are experienced learners, who in most cases believe their level of language proficiency (B2-C1) is already enough for a successful career, the language comprehensible input (Krashen, 1981) can’t be ignored. Krashen believed that the tasks should be based on the language above the current level of language proficiency, which is also our standpoint, because it corresponds with the idea that perfection or mastery, that can’t be reached, but approached, is the most powerful motivator (Pink, 2009).

Purpose of the Study

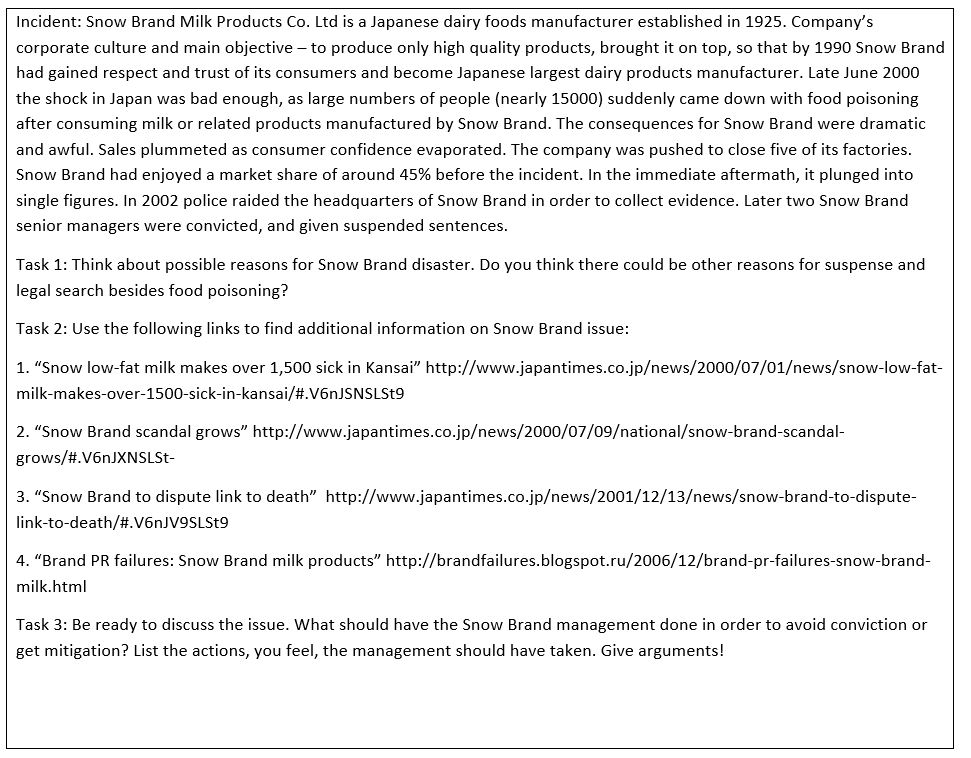

Taking everything mentioned above into account, we have developed and successfully implemented a computer-based method, called the Incident (Tsimerman, 2017). Being one of the types of situation analyses technology, the Incident nevertheless differs from role-playing or case-study dramatically. Compared with case-study, the Incident does not include detailed information on the issue under analysis (Panfilova, 2009). Since our target audience is Master Degree students majoring in management we have developed incidents based on the students’ professionally-oriented content.

The students receive a short coherent text, in our case a concise history of a company that went bankrupt or had some problems with the law. In order to boost students’ anxiety the text should not include any information on the reasons of the company’s failure. For better understanding of the idea one of the incident-based tasks represented in the Unit

Incident-based tasks correspond with the conclusions we have drawn based on the scientific research on task design analyzed, as:

1. They can be accomplished heuristically due to the following aspects:

- it’s not necessary to follow the links order given in the task to get the information needed;

- being experienced learners, Master Degree students can either scan the articles or read for gist;

- if interested students can use the autonomy provided and find any additional information themselves.

2. The content included is interesting for the teacher’s target audience:

- the content is real and shows real examples of executives’ flawed actions or inactions, bad strategy, etc. This fact stimulates students’ attention to details, helps them “walk in someone’s shoes”, learn from someone’s mistakes or demonstrate own experience and knowledge;

3. Incident-based tasks do stimulate the dopamine system, because:

- they stimulate such brain functions as: thinking, mood, motivation, wanting, seeking;

- they are aimed at gaining reward and therefore boost students’ desire for the information needed;

4. Incident-based tasks do stimulate the opioid system, because:

- the search carried out will bring results and, therefore, satisfy the desire for the information;

- the search carried out will help students demonstrate their competence in the field of their major and, thus, assist their self-affirmation.

The Incident method is relevant to CLIL as it is built on the same key principles (Coyle et al., 2010, p. 42):

“Content matter is not only about acquiring knowledge and skills, it is about the learner creating their own knowledge and understanding and developing skills” – incident-based tasks teach students how to collect and analyze the information, choose the data relevant to the issue and ignore some unimportant facts. Working with incidents means rational data search and its further implementation to dwell upon the matter, therefore, using the target language “for knowledge construction” (Dalton-Puffer, 2007, p. 65).

“Content is related to learning and thinking. To enable the learner to create own interpretation of content…” – the fact that the incident is real allows students to learn from someone’s mistakes, draw conclusions, imagine themselves experts and apply theoretical knowledge to practice.

“Thinking processes (cognition) need to be analyzed for their linguistic demands” – Considered from the point of Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), Incident-based tasks are complex and require lower-order and higher-order processing, in other words, more mental effort.

“Language needs to be learned which is related to the learning context, to learning through that language, to reconstruct the content, and to relate cognitive process…” - the “Incident” helps students improve their level of foreign language proficiency, as it is based on real articles and requires reading, vocabulary acquisition and its later cognitive implementation when writing an essay on the matter or discussing the incident in class, thus, the input-output aspect is demanding.

“Interaction in the learning context is fundamental to learning…” – incident-based tasks are complex and require in-class and out-of-class settings. In-class setting is devoted to pair or group work on the matter, which puts interaction at the core.

“…Intercultural awareness is fundamental to CLIL” – in order to correspond with this principle, incident-based tasks are to be based on situations that took place abroad. The Incident represented in the article is devoted to a Japanese company. When working with the task, students get to know particular details of the country’s regulations, law, national mentality, etc.

“CLIL is embedded in the wider educational context…and therefore must take account of contextual variables…” – the idea of the task can be applied when working with students of different majors, for example, we have also developed such tasks for Master degree students majoring in Civil Engineering, and the tasks proved their efficiency. It’s crucial to note, that incident-based tasks should be used when working with experienced students, preferably with Master Degree students, who are able to manage the cognitive load, process the information and ready to demonstrate their expertise. Otherwise, students will need “well-designed pedagogical support” (Gablasova, 2014, p. 978).

Research Methods

To check Incident-based tasks efficiency and evaluate students’ motivation and anxiety, some pedagogical experiments were conducted. We hypothesized that Incident-based tasks would stimulate experienced learners’ motivation. Since we usually work with small groups (7-12 students), to get valid results there were several experimental groups and several control groups. All students were Master’s students majoring in management with the level of language proficiency B2-C1, aged 20-21. Total number of students in the experimental group was 75 and in the control group – 68.

Incident-based tasks were included when working with the experimental groups. The processing plan of the work with the incident-based tasks was as follows:

the students read a short text on the issue considered (in-class setting; reading);

the students thought about possible reasons for the company’s problems or failures, bankruptcy (in-class setting; pair or group work, discussion);

the students followed the links that contained information and read real articles on that matter to find out the details (out-of-class setting; reading);

the students thought about the ways the company could have avoided or managed the problems (out-of-class setting; writing);

the students demonstrated professional knowledge and shared their ideas on the matter (in-class setting; discussion).

The students of the control groups were to read a long summary (around 1000 words) of the situation. Their texts contained all the information to understand the whole picture, which was later discussed. To evaluate students’ motivation and anxiety we observed the working process and polled the students of the control and experimental groups.

Our observations

Regardless of the level of language proficiency, there are always students who are either shy or simply reluctant to get involved in communication or any activity. Our observations showed that incident-based tasks caught all students’ attention, because they were eager to find out the details. Moreover, some students who kept silent during the first part of the task were active during final discussions, as they wanted to show their expertise and professional experience. As for the control groups, no particular difference in the level of students’ motivation was recorded.

Surveys

To evaluate students’ motivation, general self-assessment and opinion on the work, a survey was conducted. The students of the experimental and control groups were to rank the statements (Table

The results obtained are shown in Table

Findings

Statements 1, 2, 6, 9, 10 results indicate that incident-based tasks, even being based on the same information, outperform ordinary texts in terms of students’ motivation and anxiety stimulation. The statements aimed at content and language showings (3, 4, 5, 8) represent the fact that, both variants are more or less equal, with a bit better results of the incident-based tasks. Statement 7 results demonstrate that both groups enjoyed the final discussion on the matter; however, the showing of the experimental group is higher. We suppose that the reason for this result is connected with the fact that the students of the experimental group had more autonomy and experienced more responsibility while completing the task, since they were to find relevant information themselves.

Conclusion

The aim of this article was to demonstrate a novel task idea, which is relevant to CLIL. The dopamine and the opioid systems matters, as well as, CLIL theories considered helped develop a novel task design, which proved its efficiency. The research shows that Incident-based tasks have high potential in educational context, because they stimulate students’ motivation and anxiety not only by real situations they are based on, but also by the goal-oriented search required. Representing professional and student-centred content, incident-based tasks contribute to students’ professional skills development. Incident-based tasks can be applied in blended learning and e-learning, if modified accordingly.

References

- Almazova N.I., & Kogan M.S. (2014). Computer Assisted Individual Approach to Acquiring Foreign Vocabulary of Students Major. Human-Computer Interaction, Part II. Springer International Publishing Switzerland HCII 2014, LNCS 8524, pp. 248-257

- Anderson, L. W., & Kratwohl, D.R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman

- Berridge, K., & Robinson, T. (1998). What is the role of dopamine in reward: Hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Research Reviews, 28, 309–69

- Bruton, A. (2013). CLIL: Some of the reasons why … and why not. System, 41, 587-597

- Chostelidou, D., & Griva, E. (2014). Measuring the effect of implementing CLIL in higher education: An experimental research project, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 2169-2174. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.538

- Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Dallinger, S., Johnmann, K., Hollm, J., & Fiege, C. (2016). The effect of content and language integrated learning on students’ English and history competences – killing two birds with one stone? Learning and instruction, 41, 23-31. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.09.003

- Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007). Discourse in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Classrooms. Amsterdam: John Benjamins

- Dashkina, A.I., & Fyodorova, A.Ya. (2017). Preimushchestva predmetno-yazykovogo integrirovannogo obucheniia I gruppovoi raboty pri podgotovke studentov ekonomicheskikh spetsial’nostey k ekzamenu po inostrannomu yazyku [Advantages of Content and Language Integrated Learning in collaboration in training economic majors for foreign language examination]. Teaching Methodology in Higher Education. Vol. 6, No 20, pp. 62–71.[in Rus.] doi: 10.18720/HUM/ISSN 2227-8591.20.7

- Federal’ny Obrazovatelny Standart 38.04.04. Management Magistratura [Federal Educational Standard 38.04.02 Management Master’s Degree] (2015). [in Rus] Retrieved from http://fgosvo.ru/uploadfiles/fgosvom/380402_M_18062018.pdf

- Fryer, L.K., & Bovee, H.N. (2016). Supporting students’ motivation for e-learning: Teachers matter on and off line, The Internet and Higher Education, 30, 21-29. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.03.003

- Gablasova, D. (2014). Learning and retaining specialized vocabulary from textbook reading: Comparison of learning outcomes through L1 and L2. The Modern Language Journal, 98(4), 976-991.

- Kogan, M.S., Khalyapina, L.P., & Popova, N.V. (2017). Professionally-oriented content and language integrated learning (CLIL) course in higher education perspective In L. Gómez Chova, A. López Martínez, I. Candel (Eds.) Torres ICERI 2017 Proceedings: 10th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (pp. 1103-1112). Seville, Spain: IATED. doi: 10.21125/iceri.2017.0370

- Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning, [Online]. Available at: http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/sl_acquisition_and_learning.pdf [Accessed 17 July 2018]

- Panfilova, A.P. (2009). Innovatsionnye pedagogicheskiie tekhnologii [Innovative Pedagogical Technologies]. Moscow: Academy.[in Rus]

- Pink, D. (2009). Drive. New York: Riverhead Books

- Roussel, S., Joulia, D., Tricot, A., & Sweller, J. (2017). Learning subject content through a foreign language should not ignore human cognitive architecture: A cognitive load theory approach. Learning and Instruction, 52, 1-11 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.04.007

- Sidorenko, E.V. (2003). Metody matematicheskoi obrabotki v psikhokogii [Mathematical Treatment in Psychology]. St. Petersburg: Rech.[in Rus]

- Swain, M. (1996). Integrating language and content in immersion classrooms: Research perspectives. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 52, 4, 529-48.

- Tsimerman, E.A. (2017). Ispol’zovaniye informatsionno-kommunikatsionnykh tekhnologiy I metoda “intsidenta” v obuchenii menedzherov angliiskomu yazyku [Information and communication technologies and the incident method in teaching english for students majoring in management], St. Petersburg State Polytechnical University Journal. Humanities and Social Sciences, 8 (4) 137–145. [in Rus.] doi: 10.18721/Jhss.8414

- Tsimerman, E.A. (2018). Integrativniy predmetno-yazykovoi kurs ankgliiskogo yazyka dlya budushchikh menedzherov (uroven’ magistratury) [Content and Language Mastering]. St. Petersburg: Polytechnic University Publishing House. [in Rus.]

- Weinschenk, S. (2011). 100 things every designer needs to know about people. Voices that matter. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson education.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-050-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

51

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2014

Subjects

Communication studies, educational equipment,educational technology, computer-aided learning (CAL), science, technology

Cite this article as:

Tsimerman, E. A. (2018). Incident-Based Tasks In Clil Settings. In V. Chernyavskaya, & H. Kuße (Eds.), Professional Сulture of the Specialist of the Future, vol 51. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1295-1303). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.139