Abstract

The efforts to integrate children with ASD among neurotypical children was and still is quite a controversial subject. Theatre therapy was researched as a possible work instrument in the case of children with ASD in order to increase the development of their social and emotional abilities through recognising, expressing and understanding emotions, and also through reducing their anxiety levels towards new, unpredictable situation. The longitudinal research was implemented over a 14-month period, the data being collected in four stages, as follows: T1 – base line, T2 – post intervention, T3 – three months after the intervention, and T4 – 12 months after the intervention was completed. The experiment consisted of carrying out improvisational theatrical activities over a period of six weeks with a preschool class in which one of the children was suffering of ASD. The data has been compiled into sociograms, showing the rejecting and attraction relations towards and from the child with ASD. The data analysis indicated a progressive evolution and that the acquisitions were maintained over time.

Keywords: ASD, Improvisational theatre activities and games, school inslusion, social interaction

Introduction

Considered one of the most controversial conditions, because of its complexity autism was and is a prevailing subject for the scientific community and practitioners alike (Crișan, 2014a). According to DSM-5, ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that manifests itself throughout the life of the patient and is characterised by two key components: (1) poor development of social an communicational abilities and (2) the manifestation of repetitive interests and behaviours (APA, 2013). Lately, the prevalence of this disorder has risen spectacularly (Busby et al., 2012; Cappe et al., 2017; King & Bearman, 2009; Maenner et al., 2020), but it is not yet clear whether it is because of other factors or of a greater awareness of the disorder at a societal level and of better diagnostic tools (Crișan, 2014a; 2021a; Hertz-Picciotto & Delwiche, 2009; Hansen et al., 2015; Lobar, 2016; Maiuri, 2021).

As a reaction to this rise, research has also focused on treating policies and educational policies for children with ASD, with schools trying to identify the most effective strategies to respond to the educational and behavioural needs of children with ASD (Ferraioli & Harris, 2011) by searching for means of facilitating school and social inclusion. According to Cassady (2011) inclusion aims on one hand ensuring the educational rights of the child with disabilities along with neurotypical children, and on the other hand boosting their social inclusion and academic development (Crișan, 2021b). The efforts to integrate children with ASD among neurotypical children was and still is quite a controversial subject (Harrower & Dunlap, 2001; Lindsay et al., 2014). Recent studies have shown two patterns in the dynamics of social inclusion of these children, the two being separated by the actions and positioning of the involved agents towards this disorder (Kauffman, 2020; Maiuri, 2021). On the one hand, a negative perspective with regard to the inclusion can be identified, characterized by an opposing attitude towards the inclusion of these children in mass schools. These perceptions are based on the history of inclusion policies, such as the fact that before the 1970s it was considered unusual to educate children with autism in a public school system. They were separated both from a social and school point of view (Barnhill et al., 2011; Busby et al., 2012; Campbell, 2006; Harrower & Dunlap, 2001; Hossain, 2012), the word “autism” being associated with stigma (Kinnear et al., 2016). Campbell (2006) narrowed in on the fact that the negative attitude is rooted in the incapacity o educational agents to engage the child with ASD in educational activities, with a high degree of negligence and rejection being identified on their part. This negligence is determined in part by social, communicational and/or cognitive deficiencies of children with ASD (Crișan, 2013; Crișan 2014b; Turda et al., 2019), and also by the lack of knowledge and competence in addressing the specific deficiencies of those with ASD (Scheuermann et al., 2003; Lindsay et al., 2013; Crișan et al., 2020). This, in turn, leads to rejection, isolation and the augmentation of undesirable behaviours (Crişan & Stan, 2013; Ochs et al., 2001). In the case of children with ASD, one of the challenges in creating an inclusive educational system is to address the need for order and predictability that is specific for the disorder, and also to decrease the resistance to change of these children (Ashburner et al., 2010). This specific feature to which communicational and social deficits are added makes these children very vulnerable to the bullying phenomenon (Campbell, 2006; Humphrey & Symes, 2010), which often leads to anxiety issues (Evans et al., 2005) and low academic results (Adams et al., 2016; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008)

Therefore, one of the predictors of school inclusion is the attitude and perception of the personnel directly implicated in working with these children (Crișan et al., 2020). The more these people manifest their openness towards the philosophy of inclusion, implication in continuous training, openness towards collaboration (Campbell, 2006; Martin & Bossman, 2013; Samsel & Perepa, 2013), support and logistical aid (Anglim et al., 2018), the more we have an increase in the self-efficiency if the personnel (Majoko, 2016), and school inclusion can be successfully implemented (Cassady, 2011; Maiuri, 2021).

Problem Statement

Studies have shown that the school inclusion of children with ASD cand be implemented successfully if a series of conditions are fulfilled. According to Lindsay et al; (2014), the most frequent strategies to which teachers have resorted to in order to facilitate the inclusion of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders included: (1) resources promoting and continuous training; (2) adapting teaching methods to the needs of the children; (3) teamwork inside the school; (4) building a partnership with the family and neurotypical pupils; (5) building an accepting climate inside the classroom through raising awareness of disabilities, the need and right to education and the sensibilisation of pupils towards these aspects. Loiacono and Valenti (2010) argue that a higher level of understanding ASD and a higher degree of support cand increase inclusiveness throughout the school community, not only towards the children with ASD. These ideas are supported by other studies (Majoko, 2016; Sanz-Cervera et al., 2017).

Lindsay et al. (2013), Anglim et al. (2018) and Maiuri (2021) have outlined through their research that placing children with ASD in an inclusive educational context made easier the development of the communicational abilities and social interactions of these children, and that the behavioural patterns of neurotypical children further ease the evolution of desirable conduct of children with Autism Spectrum Deficiencies. A friendly and inclusive environment where the child with ASD benefits from caring fellows and open educators is the suitable frame for the development and social inclusion of these children (Fujii et al., 2013). Moreover, Perihan et al. (2021) have found in their meta-analysis the beneficial effects of school interventions in reducing anxiety in children with ASD.

A considerable amount of research has focused on interventions based on applied behavioral analysis (ABA) to minimise inadequate behaviours in children with ASD, but evidence-based practices (EBP) cannot be overlooked, including interventions focused on enhancing social abilities to help children with ASD in outsourcing issues (Reichow & Volkmar, 2010). Furthermore, the literature acknowledges the benefits of programmes based on social stories, visual aids (Crișan, 2015), the Programme for Educating and Enhancing Relational Abilities (PEERS), on social communication, and emotional management. The Transactional Asistance Model (SCERTS) has demonstrated that enhancing targeted abilities, such as emotional management and communication abilities, that can be evidence of the efficiency of problem internalization treatments for children with ASD (Rutherford & Johnston, 2019).

Under its various forms, Theatre Therapy has gained popularity in psychotherapy in the past decades. This way, using improvisation, puppets and clowns has become a popular way of approaching a series of psychological and emotional issues in patients. Programmes focused on Theatre Therapy are group activities that help participants develop communicational and relational abilities (Loper, 2010).

Recently, theatre therapy was researched as a possible work instrument in the case of children with ASD in order to increase the development of their social and emotional abilities through recognising, expressing and understanding emotions, and also through reducing their anxiety levels towards new, unpredictable situation (Corbett et al., 2010). Also, Loper (2010) believes that these interventions create a higher level of self-efficiency, of communicational and relational abilities in children with ASD, and an increase of their abilities to negotiate conflictual situations. Some approaches record the theatrical activities in order to later analyse it with the children suffering from ASD, who can thus identify behavioural errors and, therefore, offer alternatives through video modelling (Corbett et al., 2010). Modelling techniques are widely used to help children with ASD observe and mimic prosocial behaviours and also develop their empathy and communicational and relational abilities towards others (Corbett et al., 2010; Regan, 2008).

Improvisation is a means through which the actor is obliged to adopt a attitude towards its present situation inside a given environment. This approach is also used in therapies based on improvisational theatrical activities, teaching patients to deal with unpredictable situations that occur in day to day life (Kindler & Gray, 2010). This approach perfectly follows the needs of children with ASD, who, as a result of their deficiencies, have the need for predictability, have a rigid way of thinking and communicational and social impairments (Crișan, 2014a). All drama interventions, be them oriented towards theatre, therapy or dramatic process, place participants in fictive roles and situations, which usually reflect real life situations. This calls for the use of communicational and relational abilities, problem solving abilities, teamwork (in pairs or in small groups), a high degree of flexibility and receptivity towards other’s ideas and suggestions (O’Sullivan, 2015). Mpella and Evaggelinou (2018) have identified in their meta-analysis that theatrical games have a positive impact on the enhancement of communicational abilities, social interaction, cooperation and social awareness.

Wheater (2013) has found that using theatrical activities has a positive impact not only in the case of children with ASD, but also in the case of neurotypical children, the benefits being observed on both sides (Mpella & Evaggelinou, 2018), which is why we believed that this technique can be an efficient one in aiding the school inclusion of children with ASD.

Research Questions

Q1. Are improvisational theatrical activities efficient in facilitating the school inclusion of preschool children with ASD?

Q2. Will the interaction relations and social acceptance be maintained over a period longer than 6 months?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study consist in verifying the degree in which implementing improvisational theatrical games in pairs or in groups facilitates the inclusion of preschool children living with ASD in mass education.

Research Methods

Research design

The proposed research can be considered as part of the one-subject experiment category and is based on a longitudinal case study. The data was obtained over a period of one year, the measurements being taken in four stages: T1 – base line, T2 – post intervention, T3 – three months after the intervention, and T4 – 12 months after the intervention was completed. The data analysis was done using the sociometric method proposed by Jakob Levy Moreno (1951).

Participants

MD, aged 4, diagnosed with ASD, is included in a mass kindergarten along with 16 children with ages between three and four years old. Over the period of the intervention, the child did not benefit from other specialised intervention programmes. At the moment of the inclusion of the child in the class, he showed retardment in the development of communicational and language abilities, anxiety (fear manifested towards children who are crying) and sensory sensibility (sound made by the ambulance’s syren).

Measurement Tools

In order to measure the dependant variable, in this case the level of acceptance and integration in the educational environment, we used the following two data gathering instruments:

The observation protocol is used in order to outline the form and frequency of interaction behaviours in the preschool group, through their direct and indirect interaction with the subject, MD, both during free play activities and coordinated activities, focused on group or pair activities.

The observed data were carefully put into the observation fiche by the observer, taking into account the principles of o sociometric test. The sociometric test includes two questions that are individually posed to children, with the child having three choice answers in decreasing order, answer 1 being the most inviting/uninviting member of the group. Following the individual interviews with the preschool children, test charts were completed by the observer for each of the 16 study participants based on said interviews.

All data which was obtained was processed pursuant to the sociometric principles, thus resulting a sociogram of the preschool class. With the aid of arrows, we marked the relationships between all the children, depending on their choices, be the unilateral or reciprocal.

Research Procedure

The experiment consisted of systematically carrying out improvisational theatrical games and activities over a period of 6 weeks/ 5 days/week / 3 game activities/day, with the duration of each game between about 10 and 15 minutes. The activities were structured in two large game or activity categories: pair activities (9 activities) and group activities (13 activities), with at leas one activity from each category being carried out each day, meaning one pair activity and two group activities or one pair activity and one group activity. Both pair and group improvisational theatrical activities focus on encouraging group members to share things about themselves, building trust in one’s self and between the activity participants, developing language skills and unconditional acceptance between group members.

Findings

The data was obtained over a period of 12 months and come from each of the four stages of the research: T1 – pre-test/base line, T2 – post-test, T3 – 3 months post-intervention, T4 – 12 months post-intervention. The gathered data is presented both through the resulting sociograms and in the form of tables, as can be seen bellow, tables that are created using the sociometric method.

Results in T1 – base line

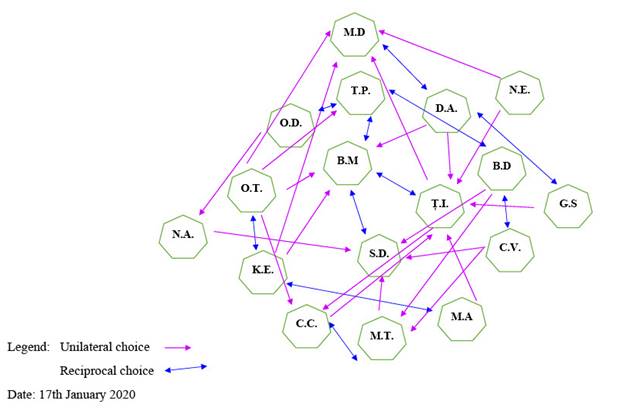

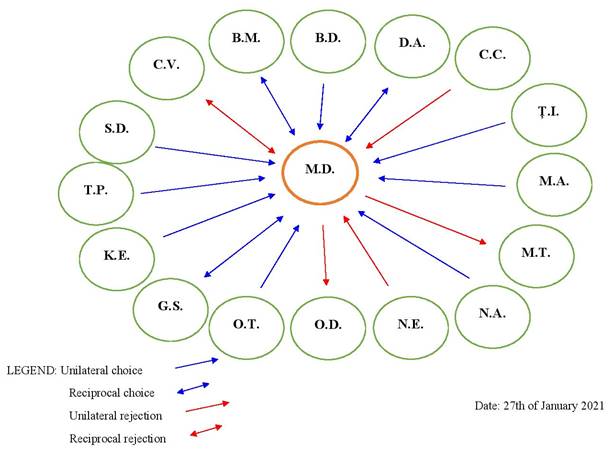

According to the data in Figure 1 and Table 1, we can observe a diverse pallet of attraction and rejection relations in the preschool group.

Taking into account the results above, we can see that out of a group of 17 preschool children, out of which one suffers from ASD, whom we identify in this case study as M.D., the attraction and rejection relations towards and from him fluctuate, as seen in Figure 1 and Table 1. Thus, 44% of preschool children in the group adopt a rejectin attitude towards M.D., while 25% manifest a unilateral attraction towards him. Manifestations of outwards socio-emotional attitudes from M.D. are completely absent in the case of unilateral attraction, with 6% in the case of unilateral rejection.

T2 – post-experimental results

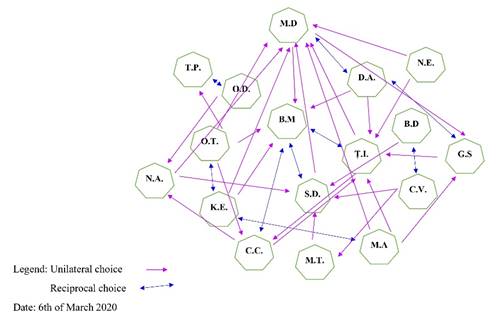

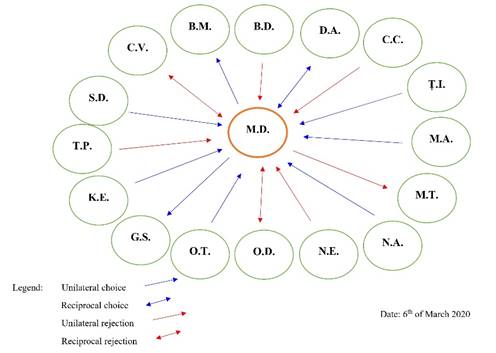

According to the data shown in Figure 2 and 3 and in Table 2, we can see an increase in the number of attraction relations both towards and from M.D.

As shown by the data in Figure 2 and 3, respectively in Table 2, we can see that the unilateral attraction choices towards M.D. declined in percentage points, reaching 25%. A decrease can be also noticed with regard to the mutual rejection percentages, in this measurement reaching 12%, meaning a 7% decrease in comparison with the base line. A major change is shown in the unilateral attraction from M.D. towards the other preschool children, where we have recorded a 12% increase, his interest towards his peers in the pre-experiment phase being null.

T3 – Post-experimental results after three months

The data obtained three months after the completion of the intervention, which is T3, is shown below in Table 3.

In the T3 evaluation, implemented 3 months after the completion of the intervention programme based on improvisational theatrical games and activities, the unilateral attractions relations towards M.D. have risen in number, with 50% of the class having an interest in socialising with him. Despite the fact that we can see a stagnation in the number of mutual rejection and unilateral rejection from M.D. we can also notice a 13 percent decrease in the unilateral rejection relations towards M.D., from 25% to 12%, as shown by Table 3. Moreover, a six percent increase can be observed with regard to the mutual attraction relations, from 6% to 12%.

T4 – Post-experimental results after 12 months

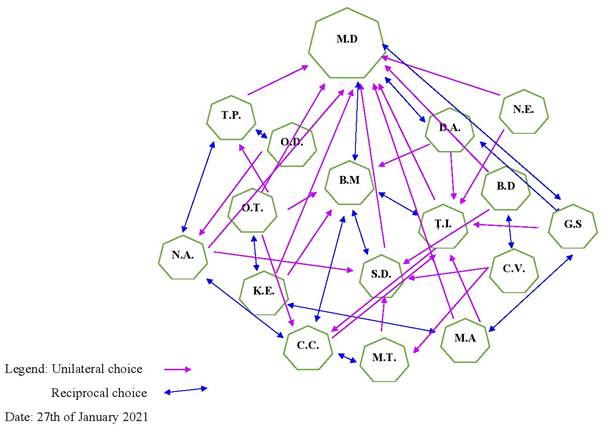

The results obtained a year after the completion of the intervention based on improvisational theatrical games and activities, named T4 according to the research design, is compiled in Figure 4 and 5 and in Table 5.

Data obtained in T4, meaning 12 months after the completion of the intervention programme based on improvisational theatrical games and activities (see Table 4), shows a 7% evolution, from 12% to 19%, in the case of mutual attraction relationships. We can still see the level of 50% in the unilateral relations towards M.D. and a rise can be observed in the rejection from M.D. relations, at 12%, as a result of the decrease from 13% to 6% in the mutual rejection relations.

Conclusion

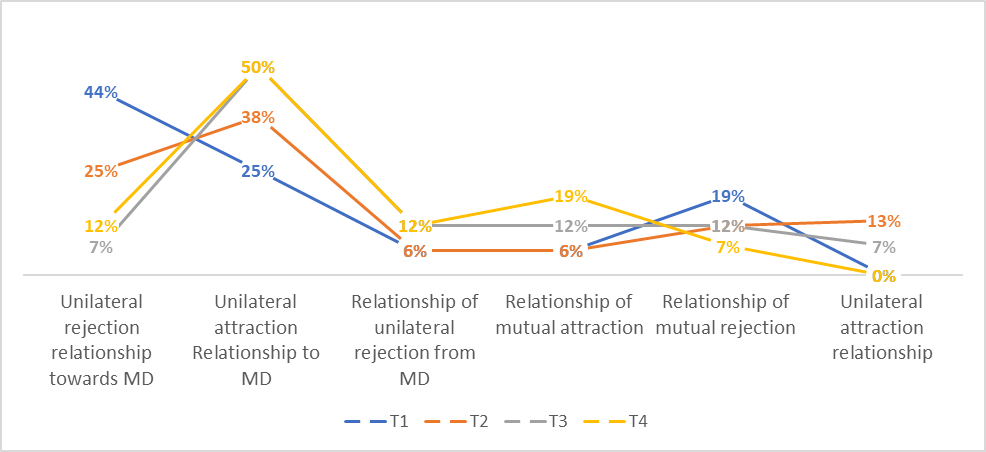

The conclusions of this one-subject experimental study will be based on the data compiled in Figure 6, which shows the evolution in the attraction and rejection relations towards and from the subject, M.D., in the preschool group from the mass-learning kindergarten, over a period of 14 months, with data being collected over a period of 12 months after the completion of the intervention based on improvisational theatrical games and activities.

As can be seen in the collected data which is systematically presented in Figure 6, we can notice a beneficial evolution in the social interactions of M.D. by comparing attraction and rejection relations. Thus, if in T1 44% of relations consisted in unilateral rejections towards M.D., we had a mild decrease to 25% immediately after the intervention (T2), to 12% three months after the intervention (T3) and to 7% 12 months after the intervention (T4), which shows a 37% decrease between T1 and T4.

Also, a significant improvement can be seen in the unilateral attraction relations towards M.D.. Therefore, if in T1 we had 25%, in T2 we can see a 13 percent improvement, only to have the percentage rise to 50% in T3 and T4. Thus, by comparing results between T1 and T4, we can see a 25% improvement in attraction relations.

Analysis of the unilateral rejection relations towards M.D. shows and increase of 6 percent from T1 to T4, and the mutual attraction levels show a plateau between T1 and T2 at 6%, only to have a 6 percent increase in T3 and a 7 percent increase in T4. Consequently, a 13 percent improvement can be seen in these relations between T1 and T4. A similar increase can be seen in the mutual rejection relations.

Last but not least, we can observe a a shift in unilateral relations of attraction from M.D., showing that if in T1 they were non-existent, they comprise 13% of the total in T2, only have a decrease in T3 to 7% and a return to the base line in T4.

By analysing the data above we will try to answer the two research questions as follows: Q1. Are improvisational theatrical activities efficient in facilitating the school inclusion of preschool children with ASD? The data we have obtained allows us to state that these activities were beneficial in the case of the studied subject, his evolution with regard to social relations being significant through the reduction in the number of rejections from M.D. and the increase in in the number of attraction relations towards M.D. The data we have obtained is similar to other data sets from the specialty literature (Kindler & Gray, 2010; Moran & Alon, 2011; O’Sullivan, 2015; Wheater, 2013).

With regard to the second research question: Q2. Will the interaction relations and social acceptance be maintained over a period longer than 6 months? Data has indicated the fact that these relations are not only maintained, but they evolve over time, with a beneficial evolution being seen by comparing data 3 months after the intervention and one year after the intervention. Our data is similar to other data sets found in the specialty literature (Goldingay et al., 2013; Mpella & Evaggelinou, 2018).

References

Adams, R., Taylor, J., Duncan, A., & Bishop, S. (2016). Peer victimization and educationaloutcomes in mainstreamed adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Journal ofAutism & Developmental Disorders, 46(11), 3557–3566.DOI: 10.1007/s10803-016-2893-3

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of MentalDisorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. DOI:

Anglim, J., Prendeville, P., & Kinsella, W. (2018). The self-efficacy of primary teachers insupporting the inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder. EducationalPsychology in Practice, 34(1), 73-88. DOI: 10.1018/02667363.2017.1391750

Ashburner, J., Ziviani, J., & Rodger, S. (2010). Surviving in the mainstream: Capacity of children with autism spectrum disorders to perform academically and regulate their emotions and behavior at school. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 18-27. DOI: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.07.002

Barnhill, G. P., Polloway, E. A., & Sumutka, B. M. (2011). A survey of personnel preparation practices in autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 26(2), 75-86. DOI: 10.1177/1088357610378292

Busby, R., Ingram, R., Bowron, R., Oliver, J., & Lyons, B. (2012). Teaching elementary children with autism: Addressing teacher challenges and preparation needs. Rural Educator, 33(2), 27-35. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ987618

Campbell, J. M. (2006). Changing children’s attitudes toward autism: A process of persuasive communication. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 18(3), 251-272. DOI: 10.1007/s10882-006-9015-7

Cappe, E., Bolduc, M., Poirier, N., Popa-Roch, M-A., & Boujut, E. (2017). Teaching students with autism spectrum disorder across various educational settings: The factors involved in burnout. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 498-508. DOI: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.07.0140742-051X

Cassady, J. M. (2011). Teachers' attitudes toward the inclusion of students with autism and emotional behavioral disorder. Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, 2(7), 1-23. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1127&context=ejie

Corbett, B. A., Gunther, J. R., Comins, D., Price, J., Ryan, N., Simon, D., Schupp, C. W., & Rios, T. (2010). Brief report: theatre as therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 41(4), 505-511. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-010-1064-1

Crișan C. A. (2013). The relation between the developmental level of communication skills and the display of challenging behaviors in children with ASD Studia Universitatis Psychologia/Paedagogia, 55–70.

Crișan C. A. (2014a). Tulburarile din spetrul autist. Diagnoza, evaluare, terapie (Autism spectrum disorders. Diagnosis, evaluation, therapy), Editura: EIKON.

Crișan C. A. (2014b). The relation between the developmental stage of expressive and receptive language among children with PDD-NOS, Studia Universitatis Psychologia/Paedagogia, 51-52.

Crișan C. A., & Stan C. N. (2013). The efficiency of LCSMA in reducing challenging behaviors in children with autism. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 13(2), 421–435.

Crişan, C. (2015). The Impact of LCSMA Based Therapy on the Overall Development Profile of Autistic Children. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 203, 109-119. DOI:

Crișan, C. (2021a). Tulburarea din spectrul autismului. Diagnoză, evaluarea, terapie (2nd Edition). Presa Universitară Clujană

Crișan, C. (2021b). AAC-Noi abordări în stimularea limbajului și comunicării specific tulburării din spectrul autismului. Polirom

Crișan, C., Albulescu, I., & Turda, E. S. (2020). Variables that influence teachers’ attitude regarding the inclusion of special needs children in the mainstream school system. Educatia, 21(18), 72-79. DOI:

Evans, D. W., Canavera, K., Kleinpeter, F. L., Maccubbin, E., & Taga, K. (2005). The fears, phobias and anxieties of children with autism spectrum disorders and down syndrome: Comparisons with developmentally and chronologically age matched children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 36(1), 3–26. DOI:

Ferraioli, S. J., & Harris, S. L. (2011). Effective educational inclusion of students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 41(1), 19–28

Fujii, C., Renno, P., McLeod, B. D., Lin, C. E., Decker, K., Zielinski, K., & Wood, J. J. (2013). Intensive cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in school-aged children with autism: A preliminary comparison with treatment-as-usual. School Mental Health, 5(1), 25–37. DOI:

Goldingay, S., Stagnitti, K., Sheppard, L., McGillivray, J., McLean, B., & Pepin, G. (2013). An intervention to improve social participation for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Pilot Study. Journal Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 18, 122-130.

Hansen, S. N., Schendel, D. E., & Parner, E. T. (2015). Explaining the increase in prevalence of autism spectrum disorders: The proportion attributable to changes in reporting practices. JAMA Pediatrics, 169, 56-62. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1893

Harrower, J. K., & Dunlap, G. (2001). Including children with autism in general education classrooms: A review of effective strategies. Behavior Modification, 25(5), 762–784. DOI: 10.1177/0145445501255006

Hertz-Picciotto, I., & Delwiche, L. (2009). The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology, 20(1), 84-90. DOI: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181902d15

Hossain, M. (2012). An overview of inclusive education in the United States. In Aitken, J. E., Fairley, J. P., Carlson, J. K., & Hossain, M. (Ed.), Communication technology for students in special education and gifted programs (pp. 1-25). IGI Global. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-60960-878-1.ch001

Humphrey, N., & Lewis, S. (2008). ‘Make me normal’: The views and experiences of pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools. Autism, 12(1), 23-46. DOI: 10.1177/1362361307085267

Humphrey, N., & Symes, W. (2010). Perceptions of social support and experience of bullying among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream secondary schools, European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25, 77-91. DOI: 10.1080/08856250903450855

Kauffman, J. (2020). On Education Inclusion, Meanings, History, Issues and International Perspectives. Routledge. DOI:

Kindler, R. C. & Gray, A. A. (2010). Theater and therapy: How improvisation informs the analytic hour. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 30, 254-266. DOI: 10.1080/07351690903206223

King, M., & Bearman, P. (2009). Diagnostic change and the increased prevalence of autism. International Journal of Epidemiology, 38, 1224-1234. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dyp261

Kinnear, S. H., Link, B. G., Ballan, M. S., & Fischbach, R. L. (2016). Understanding the xperience of stigma for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder and the role stigma plays in families’ lives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 942-953. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-015-2637-9

Lindsay, S., Proulx, M., Scott, H., & Thomson, N. (2014). Exploring teachers’ strategies for including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(2), 101-122. DOI: 10.1080/13603116.2012.758320

Lindsay, S., Proulx, M., Thomson, N., & Scott, H. (2013). Educators’ challenges of including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 60(4), 347-362. DOI: 10.1080/1034912X.2013.846470

Lobar, S. L. (2016). DSM-V changes for autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Implications for diagnosis, management, and care coordination for children with ASDs. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 30(4), 359-365. DOI: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.09.005

Loiacono, V., & Valenti, V. (2010). General education teachers need to be prepared to co-teach the increasing number of children with autism in inclusive settings. International Journal of Special Education, 25(3), 24-32. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ909033

Loper, J. M. (2010). Full spectrum access. American Theatre, 27(1), 82-87. http://web.ebscohost.com.pluma.sjfc.edu/ehost/detail?vid=3&hid=15&sid=972377b536f54e35b78e2848d04ccc3a%40sessionmgr12&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZY29wZT1zaXRl#db=a9h&AN=47599575

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., & Baio, J. (2020). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 69(4), 1.

Maiuri, A. (2021). The Inclusion of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Classrooms: Teachers’ Perspectives. https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/701

Majoko, T. (2016). Inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorders: Listening and hearing to voices from the grassroots. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 1429-1440. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-015-2685-1

Martin, D., & Bossman, M. (2013). The ever-changing social perception of autism spectrumdisorders in the United States. Social Sciences, 160-170. Retrieved fromhttp://uncw.edu/csurf/Explorations/documents/DanielleMartin.pdf

Moran, G. S., & Alon, U. (2011). Playback theatre and recovery in mental health: Preliminaryevidence. The Arts in Psychology 38(5), 318-324. DOI: 10.1016/j.aip.2011.09.002

Moreno, J. L. (1951). Sociometry, Experimental Method and the Science of Society: An Approach to a New Political Orientation. Beacon House.

Mpella, M., & Evaggelinou, C. (2018). Does theatrical play promote development of social skills in students with autism? A systematic review of the methods and measures employed in the literature, Preschool & Primary Education, 6(2), 96-118. DOI:

O’Sullivan, C. (2015). Drama and Autism. Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer Science+Business Media. DOI:

Ochs, E., Kremer-Sadlik, T., Solomon, O., & Gainer Sirota, S. (2001). Inclusion as Social Practice: Views of Children with Autism. Social development, 10(3), 399-419. DOI:

Perihan, C., Bicer, A., & Bocanegra, J. (2021). Assessment and Treatment of Anxiety in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in School Settings: A Systematic Review and MetaAnalysis, School Mental Health DOI:

Regan, T. (2008). Autism: The musical. Bunin-Murray Productions.

Reichow, B., & Volkmar, F. R. (2010). Social skills interventions for individuals with autism: Evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 149–166. DOI:

Rutherford, M., & Johnston, L. (2019). An Autism Evidence Based Practice Toolkit for use with the SCERTS™ Assessment and Planning Framework.

Samsel, M., & Perepa, P. (2013). The impact of media representation of disabilities on teachers'perceptions. Support For Learning, 28(4), 138-145. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9604.12036

Sanz-Cervera, P., Fernández-Andrés, M-I., Pastor-Cerezuela, G., & Tárraga-Mínguez, R. (2017).Pre-service teachers’ knowledge, misconceptions and gaps about autism spectrumdisorder. Teacher Education and Special Education, 40(3), 212-224.DOI: 10.1177/0888406417700963

Scheuermann, B., Webber, J., Boutot, E. A., & Goodwin, M. (2003). Problems with personnelpreparation in autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other DevelopmentalDisabilities, 18(3), 197-206. DOI: 10.1177/10883576030180030801

Turda, E. S., Crişan, C., & Albulescu, I. (2019). The Development of Executive Functions among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Open Access 9, 243. DOI:

Wheater, C. (2013). Theatre Therapy for Children with Autism. Education Masters. Paper 265.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 March 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-955-9

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-803

Subjects

Education, Early Childhood Education, Digital Education, Development, Covid-19

Cite this article as:

Crișan, C., & Varadi, C. (2022). Improvisational Theatrical Activities On The School Inclusion Process Of Children With Asd. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2021, vol 2. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 497-510). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.50