Abstract

Mule accounts are created to enable money laundering, scams, bribery, and other financial crimes. Some of the money mules are genuine lawbreakers, but many of them could be simply ignorant and practise at-risk behaviours in their banking activities. An online survey on at-risk behaviours in banking activities was participated by 201 respondents. The at-risk behaviours include disclosure of bank account information to others, performing cash transactions on behalf of others, giving ATM cards and Pins to others, and renting out the account to others. Twenty-nine per cent of the respondents gave their ATM Cards and Pins to others, while 21% rented out their bank accounts to others. Approximately 88% of those who rented out their bank accounts cited reward-seeking as their main reason. Inter-rater screening on the survey data further observed that 43% of the 201 respondents tended to be money mules. The Chi-Square Test of Independence recorded significant relationships between the tendency to be a mule or non-mule account holder and the demographic factors of the respondents, namely Gender, Academic Qualification, Employment Status, Area and Monthly Income. Binary Logistic Regression further confirmed that Academic Qualification, Employment Status, and Area are the three significant determinants. Hence, substantive awareness campaigns and preventive measures should be systematically targeted at individuals who have no university education, work in the private sector, and stay in a metropolitan. Nevertheless, this should be carefully observed and in need of further verification due to the limitation of the nature of the online survey.

Keywords: At-Risk Behaviours, Cybercrime, Commercial Crime, Mule Account, Money Mules

Introduction

A money mule is a person collecting money from a third party and under specific instruction, the money will then be transferred to another individual either by cash or any other kind (Raza et al., 2020). This implies that a money mule is a passive partner to complete the criminal process which is a cybercrime in the present context. A money mule is used and manipulated by organized criminal groups as a means for illegal activities (Abdul Rani, Syed Mustapha Nazri, et al., 2023). Because of the passive act of receiving and transferring the money under strict instruction without knowing the reasons and the context, playing the victim could be a good excuse for self-defence. Criminal investigators hardly retrieve useful clues from the money mules. Mule account activities facilitate the criminal syndicates to stay unidentified while shifting the money anytime and anywhere (EUROPOL-Public Awareness and Prevention Guides, 2019).

Cash transactions through mule accounts has been becoming easier since the 4th Industrial Revolution. The COVID-19 pandemic further speeds up online transactions widely among consumers. For instance, it was reported that a sum of money (RM3,000 to RM5,000) from a group of schoolteachers in their Touch N Go eWallet was transferred without their knowledge to other accounts (Jaafar, 2022). This is a clear example of how sensitive data can be manipulated to allow unauthorized transactions (Sisak, 2013). This is also an example of a high-tech attack of cyber fraud that involves an automated process, a small amount of stolen money that is hardly detected by the bank’s fraud detection system, and affects many victim accounts (Leukfeldt & Jansen, 2015). In this case, the “other accounts” should be the money mules that would not have sufficient information for the authority to prosecute the mastermind who is hiding behind without a trace.

The holders of the “other account” could be ordinary people who have no intention to commit a crime. The innocent agents comprise housewives, students, college students, self-employed, retirees and unemployed (Hashim & Rahman, 2020). The innocent agents must have committed at-risk behaviours that make them attracted to the rewarding fees and be manipulated to help shift the unlawful money. They at first were not interested in being money mules, but after several attempts by the fraudster, they finally gave away their ATM card and pins to the fraudster in exchange for the reward (Leukfeldt & Kleemans, 2019). In general, the reward is approximately 5 to 10% of the amount of the money (Sisak, 2013). Money mules are the most important component that completes the crime, as concluded by Florencio and Herley (2010, p. 5), “The only effective way to reduce online fraud is by making mule recruitment even harder”. Fraudsters use fake accounts to advertise attractive offers on social media such as Instagram with the usage of advanced technology to stay away from their legal responsibilities (Abdul Rani, Zolkaflil, Syed Mustapha Nazrim et al., 2023; Bekkers & Leukfeldt, 2023). They are now targeting university students and young teenagers due to their high usage of the Internet, and mostly they have low awareness of cybercrime, high unemployment and are deceived by the offers of attractive job packages (Abdul Rani, Zolkaflil, Syed Mustapha Nazrim et al., 2023; Vedamanikam & Chethiyar, 2020; Vedamanikam et al., 2022). A survey of 3000 young people of age 16 to 25 shows that 10% of the respondents had been contacted by recruiters through the social media platform (Bekkers et al., 2023).

A systematic review reported that the overall awareness among Malaysians of money mule activities is low (Ilyas et al., 2022). However, a quantitative survey of 391 respondents reported a high level of awareness on the money mule issue in Malaysia (Rosli et al., 2022). It is undeniable that there is an increasing trend of money mules in the country. Commercial crime cases recorded by the Royal Police of Malaysia increased from 27,323 cases (2020) to 31,490 cases (2021) with 28,842 fraud cases alone for the year 2021 (Business Today, November 29, 2022). Cybersecurity Malaysia reported that 2330 incidents of online fraud were recorded from January until March 2020 (Abd Rahman, 2020). Malaysian Muslim Consumers Association (PPIM) received 25,000 complaints about money mules for the past three years (Aling, July 4, 2020). The association urged the authority not to target the money mules, but the authority should act against the fraudsters who mastered all the activities and collected the money (Mokhtar, April 13, 2022). However, those who had committed at-risk behaviours with a clear intention to seek rewards should not be excused. All the financial crimes especially online fraud and money laundering will not be possible without the so-called innocent agents giving out their ATM cards or renting out their banking accounts. In many reported cases, the victims who had acted as money mules play certain significant roles to enable the transactions of illegal money. To combat the money mules, preventive measures to control individual monetary and emotional needs would not be possible because this goes against the basic human right of privacy (Abd Rahman, 2020). The visible option will be education and training to increase the awareness of the general public towards mule account issues. This is well explained by Hulsse (2017, p. 1027), “the "victimization" of the money mule enables a policy response characterized by education and awareness-raising rather than by discipline and punishment”. Apart from the awareness, it was reported that the public’s trust in law enforcement agencies has a direct effect on the morale of the agency staff in combating the money mule issues (Abdul Rani, Zolkaflil, et al., 2023).

Aston et al. (2009) conducted a demographic analysis on money mules in Australia and reported that there was an overrepresentation of males between the age of 25-34 and they suggested that more demographic data should be further analyzed to facilitate prevention activities on targeted groups of people. Prevention campaigns to raise people’s awareness of mule accounts will not be helpful if segments of the population are not given appropriate attention. Very limited empirical studies were conducted on money mules (Leukfeldt & Jansen, 2015; Leukfeldt & Kleemans, 2019), and this further limit the arrangement of strategies to stop the most vulnerable group of individuals from falling into mule recruitment. Hence, this paper presents the at-risk behaviours committed by the public, the reasons and the related determinants as stated in the following objectives:

To identify the most committed at-risk behaviour and the reasons for the behaviours.

To identify the tendency to be a money mule.

To identify the determinants of the tendency to be a money mule.

Method

Two hundred and one respondents completed an online survey on mule account behaviours. The survey was conducted using a Google form and received participation from various interested individuals with no specific limitation or requirement. Technically, it was a convenient sampling in which everyone with the link can complete the questionnaire. Initially, mule account holders were the target of the study. However, no substantive identification information is legitimately available for researchers to identify the population and to conduct purposive sampling even though the study was supported by law enforcement agencies. As a result, convenient sampling is the only accurate approach that explains the participation of the 201 respondents.

This paper covers only the findings on four at-risk behaviours of the respondents in their daily banking activities. The four single items on at-risk behaviours were measured using a nominal scale and consisted of the following:

Disclose bank account information to others

Perform cash transactions on behalf of others

Give ATM cards and PINs to others

Rent out bank account to others

The first behaviour is a common behaviour for almost everyone and is most likely not to be regarded as mule account behaviour. Disclosing bank account information specially the account number is needed for many of us to receive payment. The typical example to justify this act is to receive a monthly salary from the employer. However, this behaviour is one of the many at-risk behaviours that can lead to mule account activities. For instance, receiving unknown payments into the personal banking account and not reporting the transaction to the respective authority can be seen as part of the mule account activities.

Performing cash transactions on behalf of others, especially family members and friends is another common act in personal banking behaviours. However, this behaviour is one of the most required behaviours to operationalise a mule account and therefore it is an at-risk behaviour. Giving ATM cards and Pins to others will be seen as an at-risk behaviour, even though no active participation by the giver in making the cash transaction. By holding the ATM cards and Pins, cash transactions can be performed anytime and freely for money laundering or scam purposes, and without a trace by the authority.

Among the four at-risk behaviours, renting out a bank account to others can be a certain act of committing mule account activities. However, this is beyond the legitimation of the study to determine whether the respondents are money mules. The nearest terminology that can be used to categorise them is the concept of tendency. Hence, renting out a bank account is a clear example to indicate someone tends to be a mule account holder. However, if the individual does it for helping family or friends, it may not necessarily be clarified as an act of a money mule. Reasons are therefore important to clarify whether an act can be classified as tending to be a mule account holder.

Besides the four at-risk behaviours, the 201 respondents were further asked about their reasons for committing the behaviours. Four optional reasons were provided for the respondents to choose in explaining their involvement in the four at-risk behaviours. The four options are for helping family members and friends, for loan purposes, for employment purposes, for business purposes, and for reward-seeking purposes.

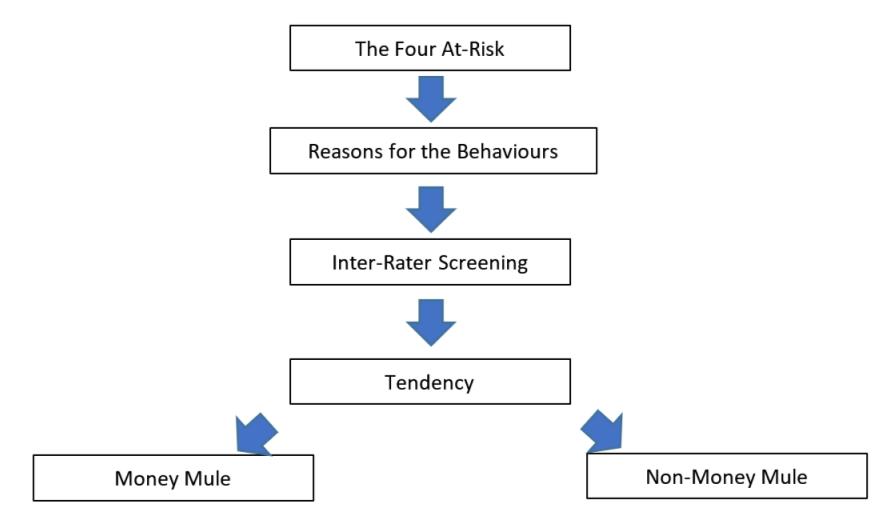

Based on the responses to the four behaviours and the given reasons, further analysis was conducted to identify the tendency to be a money mule among the 201 respondents. The analysis was conducted manually by matching the behaviours and the given reasons through an inter-rater screening by two members of the research team on the same datasheet. No discrepancy was found in the findings generated by the two members. Two criteria were used to determine a respondent for tending to be a mule account holder or a non-mule. The criteria are the following:

Those who answered 'For Reward' as the motive of performing any of the four activities.

Those who answered 'For Loan Purposes' as the motive of giving ATM cards and Pins to others.

The process of identifying and classifying the 201 respondents into the two categories of tendency, namely to be a Money Mule and a Non-Money Mule is illustrated in the following figure 1.

Results

The survey attracted 201 individuals from all over the country except Kelantan to participate and share their banking behaviours (Table 1). Slightly more females (54%) than males (46%) participated in the online survey. Fifty-eight per cent of the respondents were 35 years old and below. The majority of the respondents (78%) are Malay and more than half (52.8%) of the respondents had no university degree. Fifty-four per cent of the respondents were self-employed and worked in the private sector. Approximately 50% of the respondents were from the Klang Valley. Many of the respondents (67%) earned RM4000 or lesser per month and 68% had heard of mule account issues.

The At-Risk behaviours and the reasons

The 'At-Risk Behaviour' of each of the 201 respondents were analysed and findings are presented in the following tables.

Table 2 shows that nearly 63% of the 201 respondents had disclosed their bank account information to others. Approximately half of them had performed cash transactions on behalf of others. Twenty-nine per cent and 25.4% of respondents had given their ATM cards with PINs and rented out their accounts to others respectively.

Table 3 shows the most common reasons given by 136 respondents to justify the disclosure of bank account information were to help family/friends (47.1%) and for loan purposes (47.8%). This is followed by getting a reward (36.8%) which is a significant sign of a mule account.

Table 4 shows that loan (70.5%) is the most popular reason for giving out ATM Cards and Pin Numbers among the 61 respondents. This is followed by helping family/friends (29.5%) and getting rewards (4.9%). Conversely, none of the respondents cited business purposes as a reason for the above act.

Table 5 shows that helping family and friends is the most popular reason among the 107 respondents with 81.3% citing the reason. This is followed by getting a reward (43.9%) for loans (15.9%), business (10.3%), and employment purposes (6.5%).

Table 6 shows that seeking rewards was the dominant reason for renting out a bank account, and 87.5% of the 56 respondents cited it as the main reason. This is an irrefutable fact that they are money mules.

As presented in the above tables, it can be summarised that disclosing bank account information to others is the most common at-risk behaviour committed by respondents. The behaviour is also common among the general public, but it has not been seriously perceived as risky behaviour. Besides, helping friends and family members is another popular reason cited by the respondents in defending their at-risk behaviours.

The Tendency to be a Money Mule

Based on the inter-rater screening to categorise the respondents, 89 respondents were classified as those who tended to be money mules, while the rest 112 respondents did not tend to be money mules (Table 7). The percentage for those who had a tendency is approximately 43%, a significant figure that cannot be ignored. Although the sample of this study was not randomly selected, the finding describes the potential market to sustain the mule account activities among the 201 respondents.

Determinants of the tendency to be a money mule

The Chi-Square Test of Independence was conducted to examine relationships between the demographic factors (as presented in Table 1) and the tendency to be a money mule. The demographic factors were recorded into dichotomous groups or not more than three groups to facilitate the test.

Table 8 shows that more male respondents tended to be mule account holders, while female respondents displayed the opposite direction. The significant relationship between gender and the tendency to be a mule account holder is established with2(1, N = 201) = 6.972, p = .006. Relatively, more male respondents’ banking behaviours are in line with the criteria of mule account activities than female respondents. This finding justifies the need for future studies on the recruitment of male money mules in Malaysia (Abdul Rani, Zolkaflil, Syed Mustapha Nazrim et al., 2023).

As reported in Table 9, age had no significant relationship with the tendency to be a mule account holder, Χ2(1, N = 201) = 0.054, p = .465. Mule account behaviours cannot be detected in ranges of age among the 201 respondents.

Academic qualification was found associated with the tendency to be a mule account holder,2(1, N = 201) = 29.404, p = .001. Respondents with a Diploma or lower qualification were more likely to be associated with a tendency to be a mule account holder, while those with at least a degree or higher qualification were less likely to be found in mule account activities (Table 10).

Table 11 shows a relationship between race and the tendency to be a mule account holder cannot be established,2(1, N = 201) = 1.097, p = .190. This implies that involvement in at-risk behaviours and reward-seeking tendencies is a personal decision that is not affected by societal and cultural values.

There is a significant relationship between employment status and the tendency to be a mule holder,2(2, N = 201) = 17.006, p = .001. Respondents who are self-employed or work in the private sector are more likely to display the tendency to be a mule account holder, while those non-employed and those working the in the public sector are less likely to get involved in mule account activities (Table 12).

The 13 states recorded from the 201 respondents were further recorded into two areas, namely Klang Valley and Other Areas. Klang Valley consists of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor. Table 13 shows that living in a metropolitan may expose an individual to the risk of committing mule account activities. There is a significant relationship between areas of stay and the tendency to be a mule account holder,2(1, N = 201) = 14.222, p = .001. Those staying in Klang Valley had a higher tendency in mule account activities as compared to those staying in other areas.

Table 14 shows respondents earning RM2001 to RM6000, the middle-income group, are likely to be associated with mule account activities as compared to that earning above RM6000 or those earning RM200 and below. The relationship between monthly income and the tendency to be a mule account holder is significant,2(2, N = 201) = 17.894, p = .001.

The assumption of knowing about mule accounts will prevent individuals from taking risky behaviours and being part of the mule account activities cannot be sustained. Responses from the 201 respondents show that no significant relationship can be established between the tendency to be a mule account holder and their acknowledgement of mule account issues,2(2, N = 201) = 0.547, p = .761. Table 15 shows that 58 respondents (65%) of the 89 who were classified as tending to be mule account holders, had heard about mule account issues. This implies that knowing the mule account will not stop people from being part of the mule account activities.

Table 16 summarises the results of all the Chi-Square Tests conducted in examining relationships between demographic factors and the mule or non-mule tendency. Five out of eight demographic factors had significant relationships with the tendency. Age, Race and Awareness of Mule Account Issues were hardly associated with the tendency to be mule account holders.

Binary Logistic Regression was conducted to examine the effects of the five demographic factors (Gender, Academic Qualification, Employment Status, Area and Monthly Income) to predict the tendency to be a mule account holder.

logit = Li = B0 + B1X1 + B2X2 + B3X3 + B4X4 + B5X5

The logistic regression model was statistically significant, X2 (5, N= 201) = 60.076, p < .001. The model explained between 25.8% (Cox & Snell R2) and 34.6% (Nagelkerke) of the variance in the dependent variable (the tendency to be a mule account holder) and correctly classified 77.6% of cases. The predictive model is supported by Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (X2(7, N= 201) = 12.025, p =.100) which recorded insignificant values where p > 0.05. The equation of the model can be written as the following:

logit = Li = 6.029 + (-0.466)X1 + (-1.611)X2 + (-0.745)X3 + (-1.179)X4 + (-0.157)X5

Table 17 shows that among the five demographic factors, Academic Qualification (Diploma and below), Employment Status (Private Sector) and Area (Klang Valley) are the three determinants that added significantly to the predictive model. In other words, Individuals with lower education attainment, who work in the private sector and stay in Klang Valley have a higher likelihood to be involved in mule account activities.

Results

The majority of the 201 respondents in this study had shared their bank account information with others and approximately half of them were to help family/friends and for loans. Slightly more than half of the 201 respondents had performed cash transactions on behalf of others with a majority of them doing it to help their family/friends. These two at-risk behaviours are commonly done by many people and may not necessarily be defined as an act of money mule. Nevertheless, a significant percentage of 201 respondents gave their ATM cards with pins to others to get a loan. The combination of the behaviour and the reason is one of the real case scenarios of money mules reported in a court proceeding (Abd Rahman, 2020). Similarly, a quarter of the 201 respondents admitted that they had rented out their bank accounts to others and the main reason was reward-seeking. Hence, by screening the at-risk behaviour and reasons given, 43% of the respondents in this study can be classified as people with a tendency to be money mules. This is an important figure generated from an open and online survey conducted. Although it cannot be generalized to the larger population, the finding could be interpreted as two out of five individuals will commit at-risk behaviours of money mule.

Gender, Academic Qualification, Employment Status, State and Monthly Income are the five demographic factors that were associated with the tendency to be a money mule. The five factors significantly explained the variance of the tendency. Males were reported to have a higher tendency of being mule account holders as compared to females (Aston et al., 2009). However, logistic regression further verified that Academic Qualification (Diploma and below), Employment Status (Private Sector) and Area (Klang Valley) are the three determinants that significantly explained the tendency. The three determinants should be the main priority of targeted prevention campaigns in raising awareness among the public for not doing any illegal activities that can be related to commercial crime.

Individuals with low educational attainment may not be fully aware of the legal implication of being a passive player in the process of closing the loop of fraud. Clear, practical, and reasonable information should be designed according to the intellectual levels of the individuals. Any direct instruction without reasonable explanation would not be convincing even for children. Revisiting and revising the content to create public awareness on mule account issues should be continuously made. The information should be targeted at those working in the private sector or self-employed in the Metropolitan. Self-employed and private sector both signify the condition of instability in income. Income instability could be a strong reason for individuals choosing to be money mules. The chances of getting involved in mule account activities are higher in Metropolitan. There is a likelihood for those working in the private sector located in a Metropolitan to take at-risk behaviours to fulfil their financial needs.

As commented by Hulsse (2017), awareness-raising campaigns are mostly conducted in the home country and most of the banks get away without any responsibility. It is critical to highlight that awareness and integrity of the employees of financial institutions should not be taken easily (Abdul Rani, Zolkaflil, et al., 2023). The international perspective in cash transactions by money mules has always been left out in the campaigns. It is high time for banks to play a more proactive role in stopping suspicious new accounts and unusual transactions by utilising their international banking network. Financial support services such as services provided by The Credit Counselling and Debt Management Agency (AKPK) should also be embedded into the prevention campaigns. Individuals should not only know the prohibited behaviours in managing personal banking activities but they should be further equipped with information on how to increase their assets or cope with debts if needed. This will prevent them from considering the mule account activities as an alternative solution for their present financial problems and needs. A convincing way to prevent them from deceptive job offers and business packages as part of the mule recruitment effort.

Limitation

This is an open and online survey that embraces no specific requirement in sampling selection. As a result, the data cannot be generalized to infer the larger population. Nevertheless, the participation of the 201 respondents, provides a convenient but realistic phenomenon to be used as a reference in planning and designing prevention campaigns for the specific target groups in the general public. The findings help the financial authorities to identify the segments of society that require systematic intervention and to make mule recruitment to be an unfeasible task.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Bank Negara Malaysia through a research grant (SO Code: 21005). We would like to thank our research participants and their respective organizations. We also thank RIMC UUM and Universiti Utara Malaysia for their continuous support in money mules research.

References

Abd Rahman, M. R. (2020). Online Scammers and Their Mules in Malaysia. Jurnal Undang-undang dan Masyarakat, 26(2020), 65-72. DOI:

Abdul Rani, M. I., Syed Mustapha Nazri, S. N. F., & Zolkaflil, S. (2023). A systematic literature review of money mule: Its roles, recruitment and awareness. Journal of Finance Crime. DOI:

Abdul Rani, M. I., Zolkaflil, S., & Syed Mustapha Nazri, S. N. F. (2023). The trends and challenges of money mule investigation by Malaysian Enforcement Agency. International Journal of Business and Technopreneurship, 13(1), 37-50. http://dspace.unimap.edu.my/bitstream/handle/123456789/ 78093/The%20Trends%20and%20Challenges%20of%20Money%20Mule%20Investigation%20by%20Malaysian%20Enforcement%20Agency.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Abdul Rani, M. I., Zolkaflil, S., Syed Mustapha Nazri, S. N. F., Ahmad Nadzri, F. A., & Azemi, A. (2023). Exploring money mule recruitment: An initiative in combating money laundering. International Journal of Business and Economy, 5(1), 10-18. https://myjms.mohe.gov.my/index.php/ijbec/article/view/21131

Aling, Y. D. (2020). PPIM rekodkan 25,000 kes keldai akaun sejak 3 tahun lalu [PPIM recorded 25,000 cases of account fraud over the past 3 years]. Harian Metro. https://www.hmetro.com.my/ mutakhir/2020/07/596534/ppim-rekodkan-25000-kes-keldai-akaun-sejak-3-tahun-lalu

Aston, M., McCombie, S., Reardon, B., & Watters, P. (2009). A Preliminary Profiling of Internet Money Mules: An Australian Perspective. 2009 Symposia and Workshops on Ubiquitous, Autonomic and Trusted Computing. DOI:

Bekkers, L. M. J., & Leukfeldt, E. R. (2023). Recruiting money mules on Instagram: A qualitative examination of the online involvement mechanisms of cybercrime. Deviant Behavior, 44(4), 603-619. DOI:

Bekkers, L., Van Houten, Y., Spithoven, R., & Leukfeldt, E. R. (2023). Money Mules and Cybercrime Involvement Mechanisms: Exploring the Experiences and Perceptions of Young People in the Netherlands. Deviant Behavior, 44(9), 1368-1385. DOI:

Business Today. (2022). DOSM: Fraud leads as commercial crime rises 15.3% to 31,490 cases in 2021 from 27,323 cases the previous year. https://www.businesstoday.com.my/2022/11/29/dosm-fraud-leads-as-commercial-crime-rises-15-3-to-31490-cases-in-2021-from-27323-cases-the-previous-year/

EUROPOL-Public Awareness and Prevention Guides. (2019). Public Awareness and Prevention Guides. EUROPOL, Brussels.

Florencio, D., & Herley, C. (2010). Phishing and money mules. 2010 IEEE International Workshop on Information Forensics and Security. DOI:

Hashim, R., & Rahman, A. A. (2020). Peranan mule account dalam pengubahan wang haram di malaysia: satu perbincangan melalui kajian kes [The role of mule accounts in money laundering in Malaysia: a discussion through a case study]. International Journal of Social Science Research, 2(4), 108-145.

Hulsse, R. (2017). The money mule: Its discursive construction and the implications. Vanderbilt Law Review, 50(4), 1007-1032.

Ilyas, I. Y., Ridzuan, M. D. A. R., Mohideen, R. S., & Bakar, M. H. (2022). Level of Awareness and Understanding towards Money Mule Among Malaysian Citizens. Journal of Accounting and Finance in Emerging Economies, 8(3). DOI:

Jaafar, N. (2022). Wang dalam e-wallet lesap angkara scammer [Money in e-wallet lost by scammer]. Berita Harian. https://www.sinarharian.com.my/article/187468/berita/semasa/wang-dalam-e-wallet-lesap-angkara-scammer

Leukfeldt, R., & Jansen, J. (2015). Cyber Criminal Networks and Money Mules: An Analysis of Low-Tech and High-Tech Fraud Attacks in the Netherlands. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 9(2).

Leukfeldt, R., & Kleemans, E. R. E. (2019). Cybercrime, money mules and situational crime prevention. Criminal Networks and Law Enforcement, 75-89. DOI: 10.4324/9781351176194-5

Mokhtar, L. (2022). PPIM gesa siasat penjenayah sebenar keldai akaun [PPIM urgently investigates the real criminals of the account donkey]. Sinar Harian. https://www.sinarharian.com.my/ article/197657/BERITA/Nasional/PPIM-gesa-siasat-penjenayah-sebenar-keldai-akaun

Raza, M. S., Zhan, Q., & Rubab, S. (2020). Role of money mules in money laundering and financial crimes a discussion through case studies. Journal of Financial Crime, 27(3), 911-931. DOI:

Rosli, M. S. Z., Shakir, N. I. A. A., Ilyas, I. Y., Bakar, M. H., Mohideen, R. S., & Zakaria, M. H. A. M. (2022). The level of awareness towards money mules in Malaysia. e-Journal of Media and Society (e-JOMS), 5(1), 73-90. https://myjms.mohe.gov.my/index.php/ejoms/article/view/17372

Sisak, A. (2013). How to combat the ‘Money Mule’ phenomenon. European Policy Science and Research Bulletin, 8, 41.

Vedamanikam, M., & Chethiyar, S. D. M. (2020). Money mule recruitment among university students in Malaysia: Awareness Perspective. PUPIL: International Journal of Teaching, Education and Learning, 4(1), 19-37

Vedamanikam, M., D. M. Chethiyar, S., & M. Awan, S. (2022) Job acceptance in money mule recruitment: Theoretical view on the rewards. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 37(1), 111-117. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

29 November 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-131-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

132

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-816

Subjects

Accounting and finance, business and management, communication, law and governance

Cite this article as:

Chan, C. C., Othman, F. M., & Hisham, R. R. I. R. (2023). The Tendency to be a Money Mule: At-Risk Behaviours and the Determinants. In N. M. Suki, A. R. Mazlan, R. Azmi, N. A. Abdul Rahman, Z. Adnan, N. Hanafi, & R. Truell (Eds.), Strengthening Governance, Enhancing Integrity and Navigating Communication for Future Resilient Growth, vol 132. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 55-69). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2023.11.02.5