Abstract

Information sources are essential to develop a successful program. Currently, various information sources can be used by the government to support their program. However, the development of digital media changes the landscape in which a lot of organizations adopt digital media as a medium for disseminating their program. Rarely prior studies clearly argue that internet is the most relevant medium nowadays to reach the audience. Therefore, this research aims to examine whether there are differences among gender, age, and education regarding human trafficking from various media. The survey was conducted in East Nusa Tenggara, West Java, and East Java (N=327). The result of the study shows that relational information sources, especially non-family members, are the most frequent media that gives human trafficking information. After that, internet is the second frequently media used by the respondents. Furthermore, the analysis shows that the mean score of mass media exposure differs only by living area and generation. However, the mean score of internet exposure differs in all categories, namely gender, living area, generation, and education level. A different mean score of relational information sources occurs in generation and education level categories. Finally, this research argues that internet is not the only medium that giving high information exposure to the respondents. The respondents also frequently get information from non-family member information sources. Hence, the government should deploy those media to disseminate human trafficking information.

Keywords: Information sources, human trafficking, mass media, internet, interpersonal communication

Introduction

Human trafficking is a multinational and multidimensional crime. Men, women, and children of all ages and from all backgrounds can be victims of human trafficking, which occurs in every part of the world. Human trafficking, by definition, is the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of people through force, fraud, or deception to exploit them for profit (UNODC, 2021). The International Organization for Migration (IOM) of Indonesia recorded that there were 8.876 victims of human trafficking in Indonesia between 2005 and 2017 (Nabal et al., 2018). However, human trafficking cases in Indonesia have been rapidly growing, which reaches around 74.616 to 1 million cases each year (Zubaidah, 2015). Five provinces in Indonesia with the highest numbers of human trafficking cases have been established as the red zones by the government of Indonesia in 2017, including West Java, East Java, Central Java, East Nusa Tenggara, and West Nusa Tenggara (Antara, 2017).

On the other hand, research on the human trafficking problem in Indonesia also has grown significantly in the last ten years. The research interest covers various aspects of the human trafficking issues in Indonesia. However, most of the research addresses the causes and backgrounds of the human trafficking growing cases, regulation and laws issue, victims protection, and the government policies (Andari, 2011; Arif, 2016; Dalimoenthe, 2018; Daniah & Apriani, 2018; Darmastuti, 2015; Daud & Sopoyono, 2019; Fadli et al., 2017; Hakim, 2020; Kiling & Kiling-Bunga, 2019; Kusuma, 2015; Kusumawati, 2017; Minin, 2011; Mirsel & Manehitu, 2017; Niko, 2016; Putri & Arifin, 2019; Satriani & Muis, 2013; Sulistiyo, 2012; Sumirat, 2017; Sylvia, 2014; Wulandari, 2016; Wuryandari, 2016; Yusitarani & Sa’adah, 2020). Out of the growing numbers of research on human trafficking, there have been very few studies addressing communication efforts and information sources used by the government to eradicate human trafficking in Indonesia (Winarni & Wardani, 2015; Yusuf & Ali, 2019). However, most of the research recommends immediate communication efforts by the government, including socializing, disseminating information, and educating the society prone to human trafficking (Hidayati, 2012; Kedutaan Besar dan Konsulat AS, 2018; Minin, 2011; Utami, 2017).

Thus, regarding recommendation of the previous studies, it is critical for the government to initiate communication and information dissemination program to society to eradicate human trafficking. To reach the targeted audiences effectively, it is crucial to utilize the appropriate media based on its audiences’ characteristics. Based on its technology, media can be divided into printing technology media, chemical technology media, electronic technology media, and digital technology media (Vivian, 2014). Each technology produces different media, for example, printing technology that introduces newspapers, books, magazines, and others. This technology could encourage the growth of mass media in that era.

Meanwhile, the presence of digital technology encourages the growth of digital media that can change the landscape of mass media. Digital media can change the flow of information that is no longer only sourced from the mass media because each user can become both an information producer and a consumer. These changes have made the mass media no longer as the primary source of information for the public. They more often use digital media, especially the Internet, as the most frequently accessed source of information (Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika, 2020). This condition can be seen in which many people seek health information from the Internet more than consulting to the health workers (Allen et al., 2020; Swar et al., 2017). The Internet is often used as a source of information for politics, education, and others.

After the presence of the Internet, the mass media, especially print media, experiences a decreasing income (Abrams, 2020). In Indonesia, the Internet penetration rate has reached 73.7% of the total population; it is around 196.7 million users in 2020 (Kemp, 2021). The Internet connectivity prevalence in Indonesia is not evenly distributed across regions due to the geographical condition of Indonesia, which consists of many islands. Moreover, the population distribution is not evenly distributed as well. The Special Staff of the Minister of Communication and Information said that geographically the affordability of internet connections in Indonesia only covers 49.3% of the total land area in Indonesia. At the same time, administratively, there are more than 12,000 villages and wards in Indonesia (out of a total of 83,218 villages) that have not been reached by an internet connection (Clinten, 2020).

Geographical limitation of internet coverage in Indonesia indicates that although the internet penetration is very high, it is not evenly distributed across regions. It results in the selection of public media in areas that do not or have minimal internet connections. Three provinces of the human trafficking red zone, namely West Java, East Java, and East Nusa Tenggara (hereafter NTT), experience this condition. Those three provinces are noted to have low and uneven internet penetration rates (APJII, 2020). Seeing the high number of human trafficking cases in the red zone and its increasing trend from year to year, the strategy for communicating and disseminating information to the public in those areas must be a priority for the government.

The government needs to consider the sources of information that local people most often use to develop an adequate communication and information dissemination strategy related to human trafficking. The strategy indeed has to reach all areas in the red zone province. The knowledge of the information source choice will significantly determine the effectiveness of information dissemination and the affordability of messages to all communities in the human trafficking red zone. Therefore, the need to map the primary source of information or reference media for people in red zone provinces is urgent before developing a strategy for disseminating information on trafficking in persons.

Problem Statement

In human trafficking information, it is necessary to re-map the media that can convey information effectively to the public due to the characteristics of people in the human trafficking red zones. The media themselves are relatively different in the context of internet penetration and available media choices. The red zone provinces tend to have low and uneven penetration rates, which will impact media selection (APJII, 2020). Apart from that, mass media access and options in the red zone provinces are also limited.

Besides, the research has only focused on two sources of information, namely television and the internet. In fact, sources of information coming from family or friends still play an essential role in the Indonesian context. Indonesian people tend to trust information from family or colleagues compared to information from the mass media (Tandoc et al., 2018; Tapsell, 2018). Therefore, it is crucial to map the sources of information that most often provide information on people in red zone provinces, primarily based on gender, area of residence, age, and level of education.

Research Questions

There are several questions in this research, namely:

- Are there any exposure differences to human trafficking information from the mass media based on gender, living area, generation, and level of education?

- Are there any exposure differences to human trafficking information from the internet based on gender, living area, generation, and level of education?

- Are there any exposure differences to human trafficking information from relational information sources based on gender, living area, generation, and education level?

Purpose of the Study

This study aims to map the types of media - among mass media, internet, and relational information sources - that most often present information on human trafficking in communities in the three red zones of human trafficking cases. This study also aims to see whether there are differences in exposure based on gender, living area, generation, and level of education.

Research Methods

This study used a survey method. The survey was conducted on communities in three provinces of the red zone for human trafficking cases; West Java, East Java, and East Nusa Tenggara (NTT). The sample was selected using a quota sampling technique (N = 327) to obtain an ideal representation of each province. The survey was conducted online due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The questionnaire consists of five parts that function to measure five variables, namely gender, area of residence, age, level of education, and sources of information. The variable of the area of residence was measured by asking the district of residences, which was then categorized into urban and sub-urban areas. The age variable was measured by asking the respondents' age, which was then classified into four categories: generations Z, Y, X, and baby boomers (Dimock, 2019). The level of education was measured by asking the respondents’ latest education.

Meanwhile, the information source variable was measured using seven questions related to the media sources that most often provide information on human trafficking (α = .84). The question items were measured using the five Likert scale from never to very frequent. In mass media, three media questions are asked; television, print media, and radio. Sources of information from the internet are measured by asking for information from social media and online news portals. Relational information sources are measured by asking how often respondents get information from family and colleagues.

Furthermore, the data were analyzed using independent t-test analysis to determine the differences in information exposure based on gender and area of residence. Meanwhile, the ANOVA was used to determine the differences between the four groups in the age variable and four categories in the level of education. Besides, this research also used descriptive analysis to enrich the research findings.

Findings

Mass Media as Information Sources

The result shows that respondents have different media preferences in accessing human trafficking information. Gender, age, place of residence, and level of education are the differentiating factors in selecting information sources such as the mass media, the internet, family, and colleagues. In the context of gender, men and women have different preferences in media use (see Table 1). Women more often use social media and online news portals to find general information. Meanwhile, men more often use social media and television as sources of information.

The results also show significant differences between men and women in using radio and print media as sources of information. Female respondents do not use radio and print media as sources of information. Women's low interest in the news can drive the low level of print media consumption. Print media is one of the media formats that present a lot of news (Firdausya, 2020).

In human trafficking information, the mass media still becomes the source of information for some respondents. The results showed that there was no significant difference in the mean between men (M = 6.1, SD = 2.3) and women (M = 6.4, SD = 2.5; t (325) = -1.1, p =. 27 (two-tailed.) in obtaining information on human trafficking from the mass media the magnitude of the difference in the means (mean difference = -.304, 95% CI: -.84 to .23) was small (eta squared = .124).

This study did not conduct further analysis regarding the causes of the relatively similar mean scores. However, previous research showed no significant difference between men and women in consuming news on television even though women tended to have lower scores (Benesch, 2012; Moiseeva et al., 2019). Two factors can drive this low mean score. First, the human trafficking issue is not that much covered in the mass media. It happened since few studies examined the amount of coverage of human trafficking in the mass media. The second driving factor is the change in the information consumption pattern of the respondents where mass media is no longer the primary source of information for the respondents after the internet (Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika, 2020). However, this presumption needs to be tested in further research.

The category of residence is also one of the variables in this study to determine the role of the mass media as a human trafficking information source. The research analysis shows that there is a significant difference between urban (M = 6.5, SD = 2.3) and suburban (M = 5.9, SD = 2.5; t (325) = 2.2, p = .026 (two-tailed) areas in the exposure scores information on human trafficking through the mass media with a small difference magnitude (eta squared = .24). The respondents living in urban areas tended to have a higher mean score in mass media exposure than in suburban areas. This condition shows that the respondents in urban areas got more information about human trafficking from the mass media than those living in suburban areas (see in Table 2).

There are two hypotheses on this finding, which, of course, need to be tested further. First, urban society has many media choices, including mass and digital media (Pandey & Singhal, 2017). Meanwhile, suburban communities tend to have limited options, especially in mass media; for example, they only have access to television. Moreover, there is low literacy levels, both in the context of media access and use (Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika, 2020; Solihin et al., 2019).

This study used ANOVA to see the differences between four age categories based on generations: generations Z, Y, X, and Boomers. The results show significant differences in mass media exposure in three generations, namely Y, X, and Boomers (F (3,323) = 2.6, p = .04) with an effect size of 0.02. This effect falls into the small category.

The Post Hoc analysis using Games-Howell was carried out to see the location of the differences between groups. As a result, Generation Y (M = 5.9, SD = 2.5) is significantly different from Generation X (M = 7.2, SD = 1.7) and Boomers Generation (M = 8, SD = 1). The different characteristics of generation Y from generation X and Boomer are the driving forces for the difference in scores. The level of generation X and Boomers’ consumption of television, radio, and newspapers is higher than generation Y, who prefers to access the online video (Kaonang, 2020). Meanwhile, Group Z (M = 6.3, SD = 2.5) does not differ from the other three groups.

The level of education in this study was also used to see differences in mass media exposure as a source of information on human trafficking. A one-way between-group analysis of variance was conducted to explore the impact of education on mass media choice. The educational level is divided into four groups (1 = Elementary School, 2 = Junior High School, 3 = Senior High School, 4 = Bachelor and above). There is no significant difference between groups at the p> .05: F (3, 325) = 2.04. and effect size = 0.01. The implication is that the level of education does not significantly play a role in differences in the mass media exposure as a source of information on human trafficking.

The changing media consumption pattern towards digital media causes no significant difference in mass media exposure related to human trafficking. The respondents with various educational backgrounds have started to switch to digital media, so mass media exposure is low. In other words, the mass media consumption patterns among the respondents are relatively the same.

The four analyses above show that the difference in exposure to human trafficking information from the mass media only occurs in the area of residence and age. Meanwhile, gender and education level do not make a significant difference to mass media exposure. Based on these findings, this study recommends using mass media as a medium of socialization. Furthermore, information on human trafficking should be targeted at individuals who live in urban areas and are part of generation X and Boomers.

Internet as Information Sources

The second question of this research is to determine whether there are differences in exposure to human trafficking information from the internet based on gender, area of residence, age, and level of education. This study used an independent t-test analysis to determine whether there were differences in internet exposure based on gender and area of residence (see Table 3).

The analysis shows that there is a significant difference in scores between men (M = 6.04, SD = 2.02) and women (M = 6.5, SD = 1.9) on exposure to human trafficking information from the internet with a small effect size (eta squared = .27). Women tend to have higher mean scores than men in internet use. It means that women tend to be more frequently exposed to human trafficking information from the internet when compared to men.

This finding does not align with the internet penetration surveys conducted by various institutions, stating that men have higher internet penetration than women (Johnson, 2021; Kusnandar, 2019). It means that, supposedly, men are more frequently exposed than women. However, this survey was conducted in the context of the use of internet in general. Several studies examining differences in motives for using the internet based on gender have found that women have higher scores in using the internet for information retrieval when compared to men (Brell et al., 2016; Weiser, 2000). In the context of this research, women use the internet to get information related to human trafficking.

The results also show a significant difference in scores between respondents who live in urban areas (M = 6.6, SD = 1.8) and sub-urban (M = 6.04, SD = 2.06) related to the exposure to information from the internet. The respondents in urban areas have a higher mean score than those in suburban areas since internet access is not evenly distributed in Indonesia.

Internet infrastructure tends to be centered on Java and urban centers (APJII, 2017).

APJII also revealed that internet penetration in urban areas is more significant than in suburban areas (APJII, 2019).

As a result, urban people are more often exposed to human trafficking information from the internet because of the high intensity of its use.

The next variables tested in this study are age and education. Table 4 shows that age can create a difference in the mean score of exposure to human trafficking information from the internet. The analysis shows that this difference is statistically significant between generation Z (M = 6.6, SD = 1.8), generation Y (M = 6.3, SD = 1.95), generation X (M = 5.1, SD = 2.35), and the Boomers generation (M = 3.6, SD = 1.94). The effect size difference is small (eta squared = .08).

The Post Hoc analysis shows that generation Z differs significantly from generation X and Boomers in their exposure to information from the internet. Likewise, generation Y differs significantly from generation X and Boomers. The significant difference between generations Z and Y with generations X and Boomers is the extensive age range. Generation Z and Y are digital natives who have been accustomed to using the internet since childhood and have made it their primary source of information and entertainment (Kaonang, 2020). It is different from generation X and Boomers, who are accustomed to using television and newspapers as sources of information (Kaonang, 2020; Mitchell et al., 2020). Therefore, generations Z and Y have higher exposure scores than the other two generations. Also, the characteristics of generation X and Boomers as digital immigrants make them unfamiliar (fluent) with the internet so that the frequency of use is low (Wang et al., 2013).

The findings differ when generation Z is compared with generation Y. This is because generations Z and Y have relatively the same characteristics regarding internet usage patterns. However, both generations have a high frequency of internet use, so the opportunities for exposure to human trafficking information are also getting higher. Meanwhile, generation X is also not significantly different from the Boomer generation since both generations have a low frequency of internet usage. Therefore, it makes the chance of being exposed to information from the internet is also lower.

The level of education also affects the mean score of human trafficking information exposure from the internet. The data analysis conducted shows that there is a significant difference between respondents with the level of primary school education (M = 3.3, SD = 2.3), junior high school (M = 3.4, SD = 1.6), high school (M = 5.9, SD = 1.9), and undergraduate (M = 6.9, SD = 1.7). Post-hoc analysis shows that respondents with primary school education have significantly different levels of information exposure from those with a bachelor’s degree. The respondents with a junior high school education have a significantly different level from the high school and bachelor groups; the high school group has significantly different levels from junior high school and bachelor groups.

This study does not examine further the causes of the differences in information exposure from the internet based on education level. However, this study argues that the difference between primary school and bachelor respondents is due to the primary school respondents’ low internet penetration rate compared to the bachelor and higher-level respondents (APJII, 2019; Pew Research Center, 2017). As a result, respondents with only primary school education are rarely exposed to information from the internet.

Based on the explanation of the analysis of human trafficking information exposure from the internet above, the government or any other related institutions are advised to use the internet as a medium for disseminating human trafficking information. The implementation is possible when the targets are female audiences or Generation Z and Y who live in urban areas with at least a high school educational level. The internet is the right choice for women, especially when accompanied by advocacy activities (Coffé & Bolzendahl, 2010).

Relational Information Sources

This study chooses interpersonal communication because communication between communicators can foster credibility so that the information transfer process will run quickly. Interpersonal communication is also an option that the government or related institutions often choose to disseminate information. In the context of this study, interpersonal communication is grouped into two, namely interpersonal communication involving family members (family communication) and communication involving non-family members such as friends, colleagues, and others (non-family communication).

The results show that there is no difference in exposure to human trafficking information from family and non-family sources based on gender and place of residence (see Table 5). Men and women are both often exposed to information on trafficking from families and non-families. However, both genders have higher mean scores in the non-family communication category than family. It means that they often get information related to human trafficking from outside the family.

Relational information sources that usually comes from family and friends, are often a favourite source of information in various contexts (Allen et al., 2020; Endsley et al., 2014). It is because family and friends have higher credibility compared to other relational information sources. Sources of information from non-family such as friends are usually used more frequently when it comes to more personal and sensitive information or issues. Meanwhile, most often, respondents who live in urban and suburban areas often get information about human trafficking from non-family sources.

The information exposure received between generations through the family has different mean scores. Generation Z (M = 5.3, SD = 2.3) and Generation Y (M = 5.6, SD = 2.6) have different scores than Generation X (M = 7.5, SD = 2.2). Meanwhile, the Boomer Generation (M = 5.4, SD = 2.3) has no difference in scores from other generations. These findings show that Generation X is the most frequently-informed about human trafficking from families. This score differs significantly from Generations Z and Y, with lower mean scores.

There is no difference in the mean score between levels of education in obtaining exposure to human trafficking information from the family. Respondents with a primary education level have a higher average mean score when compared to other respondents. It means that the respondents with primary school education are more likely to get information about trafficking from their family than from other groups. This score is still relatively lower than the mean score of the non-family sources (M = 8.6, SD = 2.5).

Non-family sources provide information on human trafficking that varies between generations and levels of education. There is a significant difference in the mean score based on the generation category with a relatively small effect size (η2 = .02). The Post Hoc analysis showed that this difference was found between the Boomers (M = 4.2, SD = 1.78) and the Y (M = 7.34, SD = 2.5) and the X (M = 7.7, SD = 2.4) generations. Meanwhile, Generation Z is no different from other generations. Generation X has the highest mean score compared to other generations. In addition, Generation X most often gets information on human trafficking from non-family members.

The differences in the mean score are also found between the respondents with different levels of education. There is a significant difference with a small effect size (η2 = .02) between levels of education. The Post Hoc analysis found that the respondents with a high school education level (M = 6.6, SD = 2.6) differed significantly from those with a bachelor's degree and above (M = 7.5, SD = 2.9). The respondents with primary and junior high school education have no difference in scores with the other respondents. However, the respondents with primary education often hear information about human trafficking from relational information, especially non-family members.

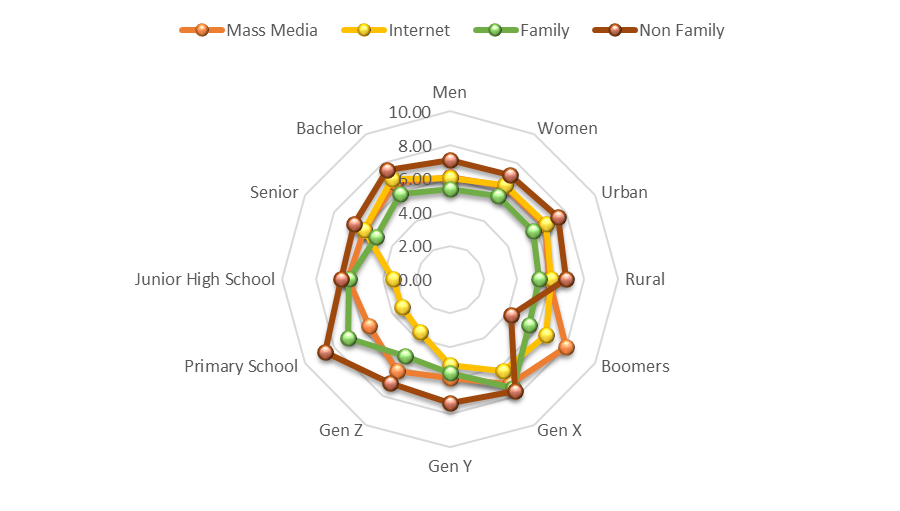

Based on the explanation of the research results above (see Figure 1), each source of information provides different information on human trafficking exposure to the research respondents. Female respondents have a higher mean score than men in obtaining exposure to human trafficking information from mass media, the internet, and relational information sources. However, these scores do not differ significantly in exposure to mass media and relational information. A very significant difference in scores was found on the internet exposure. Another interesting finding is that women and men often get information on trafficking from non-family information sources and the internet. Therefore, the government can use these two media in the future in disseminating human trafficking information.

The same thing was also found on the respondents who live in urban areas. They are more frequently exposed to human trafficking information from non-family information sources, such as friends or colleagues, and the internet. However, the average respondents' exposure scores in sub-urban areas are lower than those in urban areas. While in fact, many cases of human trafficking target people who live in sub-urban areas. This finding indicates that the government should be more aggressive in disseminating human trafficking information to sub-urban communities using relational information sources and the internet.

The exposure to human trafficking information also differs significantly between generations. Generation X and Boomers are closer and often use mass media such as television and newspapers as a source of information. It is different from generations Y and Z, who often use the internet as the source of information. The results also discovered a significant difference in the level of information exposure between generations from family and non-family sources. Generation X is the generation that most often gets information on trafficking from families and non-families. Meanwhile, the Boomers generation often gets information about human trafficking from the mass media and their families.

Generation X has a different pattern of information exposure compared to its predecessor generations. Generation X often gets information from relational information sources such as family or relatives rather than mass media and internet. Meanwhile, generations Y and Z have relatively the same pattern of exposure to information on human trafficking. They more often get information from friends and the internet than the mass media and family. In the future, the government can use these two media to spread information to generations Y and Z. Another interesting finding regarding generations Y and Z is that Generation Z has a higher score compared to the previous generations. It means that generation Z gets much more information, which may be influenced by the motive of media use or the duration of its use. Therefore, this study recommends that further research examine differences in motives and patterns of information seeking in generations Y and Z.

The level of exposure to human trafficking information also differs among levels of education. The respondents with primary school education level often get information about human trafficking from relational information sources and mass media. Meanwhile, the junior high school and high school education level respondents have a relatively similar exposure pattern; they were more frequently exposed to information from relational information sources, especially from friends or colleagues. The respondents with bachelor education level and above also make friends or colleagues a proven source of information with a high level of information exposure, also the internet. The information exposure and education level findings show a similarity among respondents; they are both more frequently exposed to information from friends and the internet. Therefore, the government should optimize the internet to disseminate information related to human trafficking.

Conclusion

Mass media, the internet, and relational information sources provide different exposure on human trafficking information towards the respondents. The mass media gives a high exposure to female respondents or those who live in urban areas or the Boomers respondents or the respondents with bachelor and above education level. Gender and education levels are not sufficient to produce differences in mass media exposure. Meanwhile, the area of residence and generation category can create different levels of information exposure from the mass media.

The internet provides high exposure to human trafficking information on female respondents or who live in urban areas or generation Z or the respondents with a bachelor degree or above. Although the average level of internet exposure is high among respondents, the exposure to information from friends or colleagues is much higher.

On the other hand, families as the source of information most often gives the information exposure to female respondents, the respondents who live in urban areas, the respondents from generation X, and the respondents with primary school education level. Meanwhile, friends or colleagues as the source of information provide a lot of exposure to female respondents, the respondents who live in urban areas, the respondents from Generation Y, and the respondents with primary school education level.

Based on the findings, the present study proposes that future research should draw on news analysis regarding their frequency and framing on human trafficking information, while, at the same time, future research should explore the government activities in socializing the information. It is essential to comprehend whether the government lacks in informing or it is the media that sees human trafficking information as something that has no news values.

However, the current research has limitations regarding the sampling technique since it employed quota sampling, which could not be generalized. Therefore, future research should use probability sampling. Furthermore, they can combine it with qualitative methods to acquire a comprehensive explanation.

Acknowledgments

The study is a part of a larger study entitled "SDGs' Acceleration through the Optimization of Government Communication and the Role of Civic Society in the Attempt to Eradicate Human Trafficking", which is wholly entirely funded with the research grant provided by the Directorate General of Higher Education, Ministry of Education and Culture, Republic of Indonesia.

References

Abrams, K. Von. (2020, October). The Global Media Intelligence Report 2020. Insider Intelligence Trends, Forecasts & Statistics.

Allen, F., Cain, R., & Meyer, C. (2020). Seeking relational information sources in the digital age: A study into information source preferences amongst family and friends of those with dementia. Dementia, 19(3), 766–785.

Andari, A. J. (2011). Analisis Viktimisasi Struktural Terhadap Tiga Korban Perdagangan Perempuan Dan Anak Perempuan [Analysis of Structural Victimization of Three Victims of Trafficking in Women and Girls]. Jurnal Kriminologi Indonesia, 7(3), 307–319.

Antara. (2017). Lima Provinsi Masuk Zona Merah Perdagangan Manusia [Five Provinces Included in the Human Trafficking Red Zone]. https://nasional.republika.co.id/berita/nasional/umum/17/11/23/ozvhkw383-lima-provinsi-masuk-zona-merah-perdagangan-manusia

APJII. (2017). Penetrasi & Perilaku Pengguna Internet Indonesia 2017 [Indonesian Internet User Behavior & Penetration 2017]. Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia.

APJII. (2019). Penetrasi & Profil Perilaku Pengguna Internet Indonesia Tahun 2018 [Penetration & Behavior Profile of Indonesian Internet Users in 2018]. Apjii.

APJII. (2020). Laporan Survei Internet APJII 2019-2020 [APJII Internet Survey Report 2019-2020]. Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia.

Arif, G. W. (2016). Peran International Organization for Migration (IOM) dalam Mengatasi Perdagangan Manusia di Indonesia tahun 2010-2014. JOM FISIP, 9(2), 10.

Benesch, C. (2012). An Empirical Analysis of the Gender Gap in News Consumption. Journal of Media Economics, 25(3). https://doi.org/147-167.

Brell, J., Valdez, A. C., Schaar, A. K., & Ziefle, M. (2016, July). Gender differences in usage motivation for social networks at work. In International Conference on Learning and Collaboration Technologies (pp. 663-674). Springer, Cham.

Clinten, B. (2020, September). Cakupan 4G di Indonesia Kurang dari Setengah Keseluruhan Wilayah [4G Coverage in Indonesia Less than Half of the Entire Region].

Coffé, H., & Bolzendahl, C. (2010). Same game, different rules? gender differences in political participation. Sex Roles, 62(5–6), 318–333.

Dalimoenthe, I. (2018). Pemetaan Jaringan Sosial dan Motif Korban Human Trafficking pada Perempuan Pekerja Seks Komersial [Mapping of Social Networks and Motives of Victims of Human Trafficking in Women Commercial Sex Workers]. Jupiis: Jurnal Pendidikan Ilmu-Ilmu Sosial, 10(1), 91.

Daniah, R., & Apriani, F. (2018). Kebijakan Nasional Anti-Trafficking dalam Migrasi Internasional. Jurnal Politica Dinamika Masalah Politik Dalam Negeri dan Hubungan Internasional, 8(2).

Darmastuti, R. R. (2015). Kerjasama Polri Dan Iom Dalam Menanggulangi Perdagangan Manusia Di Indonesia Tahun 2007-2013 [Cooperation between the Police and IOM in Combating Human Trafficking in Indonesia in 2007-2013]. Journal of International Relations, 1(2), 110–117.

Daud, B. S., & Sopoyono, E. (2019). Penerapan Sanksi Pidana Terhadap Pelaku Perdagangan Manusia (Human Trafficking) Di Indonesia [Application of Criminal Sanctions Against Human Trafficking in Indonesia]. Jurnal Pembangunan Hukum Indonesia, 1(3), 352.

Dimock, M. (2019). Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center, 17(1), 1-7.

Endsley, T., Wu, Y., & Reep, J. (2014). The source of the story: Evaluating the credibility of crisis information sources. ISCRAM 2014 Conference Proceedings - 11th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, 1(1), 160–164.

Fadli, M. A., Fakultas, M., Universitas, H., Kuala, S., Hukum, F., & Syiah, U. (2017). Studi Komparatif tentang Pengaturan Tindak Pidana Pendahuluan Undang Undang Nomor 21 Tahun 2007 tentang Pemberantasan Tindak Pidana Perdagangan [A Comparative Study on the Regulation of Criminal Acts Preliminary to Law Number 21 of 2007 concerning the Eradication of Trafficking Crimes. Orang (UUPTPPO), 1(1), 93–102.

Firdausya, I. (2020). Survei: Perempuan Indonesia Jarang Konsumsi Berita [Survey: Indonesian Women Rarely Consumption of News].

Hakim, L. (2020). Analisis Ketidak Efektifan Prosedur Penyelesaian Hak Restitusi Bagi Korban Tindak Pidana Perdagangan Manusia (Trafficking) [Analysis of the Ineffectiveness of Procedures for the Settlement of Restitution Rights for Victims of the Crime of Human Trafficking (Trafficking)]. Jurnal Kajian Ilmiah, 20(1), 43-58.

Hidayati, M. N. (2012). Upaya Pemberantasan dan Pencegahan Perdagangan Orang Melalui Hukum Internasional dan Hukum Positif Indonesia [Efforts to Eradication and Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Through International Law and Indonesian Positive Law]. Jurnal Al-Azhar Indonesia Seri Pranata Sosial, 1(3), 163–174.

Johnson, J. (2021, January). Global internet usage rate by gender and region 2019. Statista.

Kaonang, G. (2020, May). [Infografik] Tren Konsumsi Media Selama Pandemi Berdasarkan Usia Konsumen [Media Consumption Trends During a Pandemic Based on Consumer Age]. Dailysocial.

Kedutaan Besar dan Konsulat AS, I. (2018). Laporan Tahunan Perdagangan Orang 2018 [Trafficking in Persons Annual Report 2018]. https://id.usembassy.gov/id/our-relationship-id/official-reports-id/laporan-tahunan-perdagangan-orang-2018/

Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika. (2020). Status Literasi Digital Indonesia 2020. Jakarta.

Kemp, S. (2021, February). Digital in Indonesia: All the Statistics You Need in 2021. DataReportal – Global Digital Insights.

Kiling, I. Y., & Kiling-Bunga, B. N. (2019). Motif, Dampak Psikologis, Dan Dukungan Pada Korban Perdagangan Manusia Di Nusa Tenggara Timur [Motives, Psychological Impact, and Support for Victims of Human Trafficking in East Nusa Tenggara]. Jurnal Psikologi Ulayat, 6, 83–101.

Kusnandar, V. B. (2019, July). Survei 2018: Pengguna Internet Didominasi Laki-laki. [2018 Survey: Male-dominated Internet Users]. Databoks.

Kusuma, A. A. (2015). Efektivitas Undang-Undang Perlindungan Anak Dalam Hubungan Dengan Perlindungan Hukum Terhadap Anak Korban Perdagangan Orang Di Indonesia [The Effectiveness of the Child Protection Act in Relation to the Legal Protection of Children Victims of Trafficking in Persons in Indonesia.]. Lex Et Societatis, 3(1).

Kusumawati, M. P. (2017). Ironi Perdagangan Manusia Berkedok Pengiriman “Pahlawan Devisa Negara.” [Human Trafficking under the guise of Shipping “Heroes of Foreign Exchange.”] Jurnal Hukum Novelty, 8(2), 187.

Minin, D. (2011). Strategi Penanganan Trafficking di Indonesia [Trafficking Handling Strategy in Indonesia]. Kanun Jurnal Ilmu Hukum, 54, 21–31.

Mirsel, R., & Manehitu, Y. C. (2017). Komoditi yang Disebut Manusia: Membaca Fenomena Perdagangan Manusia di NTT dalam Pemberitaan Media [Commodities Called Humans: Reading the Phenomenon of Human Trafficking in NTT in Media Coverage]. Jurnal Ledalero, 13(2), 365.

Mitchell, A., Jurkowitz, M., Oliphant, J. B., & Shearer, E. (2020, July). Americans Who Mainly Get Their News on Social Media Are Less Engaged, Less Knowledgeable. Pew Research Center.

Moiseeva, E., Sivrikova, N., Ekzhanova, E., & Reznikova, E. (2019). Gender and age features of media consumption results of the survey of people aged 12-20. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series.

Nabal, A. R. J., Wea, L. V., & Gulo, S. (2018). Telaah Human Trafficking di Indonesia [Study Human Trafficking in Indonesia].

Niko, N. (2016, October). Kemiskinan Sebagai Penyebab Strategis Praktik Humman Trafficking Di Kawasan Perbatasan Jagoi Babang (Indonesia-Malaysia) Kalimantan Barat [Poverty as a Strategic Cause of Human Trafficking Practices in the Jagoi Babang Border Area (Indonesia-Malaysia) West Kalimantan]. In Prosiding Seminar Nasional INDOCOMPAC.

Pandey, A., & Singhal, B. P. (2017). Access to Mass Media Among Urban and Rural Teenagers of India. Research Chronicler: International Multidisciplinary Peer-Reviewed Journal, V(III), 41–47.

Pew Research Center. (2017, January). Social media use by education. Pew Research Center.

Putri, A. R. H., & Arifin, R. (2019). Perlindungan Hukum Bagi Korban Tindak Pidana Perdagangan Orang di Indonesia [Legal Protection for Victims of Human Trafficking Crimes in Indonesia]. Res Judicata, 2(1), 170.

Satriani, R. A., & Muis, T. (2013). Studi tentang perdagangan manusia pada remaja putri jenjang sekolah menengah di kota Surabaya. [Study of human trafficking in high school girls in the city of Surabaya] Jurnal BK Unesa, 04(1), 67–78.

Solihin, L., Hijriani, I., Raziqiin, K., & Zaenuri, M. (2019). 34 Provinces Reading Literacy Activity Index. Center for Research on Education and Culture Policy, Research and Development Agency, Ministry of Education and Culture.

Sulistiyo, A. (2012). Perlindungan Korban Kekerasan Kejahatan Perdagangan Manusia dalam Sistem Hukum Pidana Indonesia [Protection of Victims of Violence in the Crime of Human Trafficking in the Indonesian Criminal Law System]. Pandecta (Jurusan Hukum Dan Kewarganegaraan, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial Universitas Negeri Semarang), 7(2).

Sumirat, I. R. (2017). Perlindungan Hukum terhadap Perempuan dan Anak Korban Kejahatan Perdagangan Manusia [Legal Protection for Women and Children Victims of the Crime of Human Trafficking]. Jurnal Studi Gender Dan Anak, 19–30.

Swar, B., Hameed, T., & Reychav, I. (2017). Information overload, psychological ill-being, and behavioral intention to continue online healthcare information search. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 416–425.

Sylvia, I. (2014). Faktor Pendorong dan Penarik Perdagangan Orang (Human Trafficking) di Sumatera Barat [Pushing and Pulling Factors of Human Trafficking in West Sumatra]. Humanus, XIII(2), 193–202.

Tandoc, E. C., Ling, R., Westlund, O., Duffy, A., Goh, D., & Zheng Wei, L. (2018). Audiences’ acts of authentication in the age of fake news: A conceptual framework. New Media and Society, 20(8), 1–19.

Tapsell, R. (2018). Disinformation and democracy in Indonesia. New Mandala, 12.

UNODC. (2021). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/

Utami, P. (2017). Upaya Pemerintah Indonesia dalam Mengatasi Human Trafficking di Batam [Indonesian Government's Efforts in Overcoming Human Trafficking in Batam]. Hubungan Internasional, 5(4), 1257–1272.

Vivian, J. (2014). Media of Mass Communication. Pearson Education.

Wang, Q., Myers, M. D., & Sundaram, D. (2013). Digital natives and digital immigrants: Towards a model of digital fluency. Business and Information Systems Engineering, 5(6), 409–419.

Weiser, E. B. (2000). Gender differences in Internet use patterns and internet application preferences: A two-sample comparison. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 3(2), 167–178.

Winarni, R. W., & Wardani, W. G. W. (2015). Produksi film animasi sebagai media kampanye anti kejahatan perdagangan manusia [Production of animated films as a campaign medium for anti-human trafficking crimes]. Jurnal Desain, 03, 37–48. https://doi.org/DOI:

Wulandari, A. R. A. (2016). Kerjasama bnp2tki dengan iom dalam menangani human trafficking tenaga kerja Indonesia di Malaysia Periode 2011-2015 [Kerjasama bnp2tki cooperation with iom in dealing with human trafficking of Indonesian workers in Malaysia for the period 2011-2015]. Journal of International Relations, 2(1), 189–196.

Wuryandari, G. (2016). Menelaah Politik Luar Negeri Indonesia dalam Menyikapi Isu Perdagangan Manusia [Examining Indonesia's Foreign Policy in Responding to the Issue of Human Trafficking]. Jurnal Penelitian Politik, 8(2), 17.

Yusitarani, S., & Sa’adah, N. (2020). Analisis yuridis perlindungan hukum tenaga migran korban perdagangan manusia oleh pemerintah Indonesia [Juridical analysis of the legal protection of migrant workers victims of human trafficking by the Indonesian government]. Jurnal Pembangunan Hukum, 2(1).

Yusuf, M. F., & Ali, M. (2019). Komparasi Berita Tenaga Kerja Indonesia di Arab Saudi dalam Surat Kabar Elektronik Detikcom dan Sabq.org. [News Comparison of Indonesian Migrant Workers in Saudi Arabia in the Electronic Newspapers Detikcom and Sabq.org.] Communicatus: Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi, 2(1), 1–16.

Zubaidah, N. (2015). Korban Human Trafficking di Indonesia Capai 1 Juta per Tahun [Human Trafficking Victims in Indonesia Reach 1 Million per Year]. https://nasional.sindonews.com/berita/1036327/15/korban-human-trafficking-di-indonesia-capai-1-juta-per-tahun#:~:text=International Organization for Migration (IOM,74.616 hingga 1 juta pertahun

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 January 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-122-5

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

123

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-494

Subjects

Communication, Media, Disruptive Era, Digital Era, Media Technology

Cite this article as:

Limilia, P., Pratamawaty, B. B., & Dewi, E. A. S. (2022). Information Sources and Demographic Profiles on Human Trafficking Information in Indonesia. In J. A. Wahab, H. Mustafa, & N. Ismail (Eds.), Rethinking Communication and Media Studies in the Disruptive Era, vol 123. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 12-27). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2022.01.02.2