Abstract

The article deals with the problem of master students’ competence for speech production on the topic of their scientific work when they are completing the first year of masters’ courses and at the final stage of learning the English language as a second language. The objective of the paper is to find out the level of readiness to produce utterances in English in the professional context concerning master’s scientific work, to analyse the ability to explain the objective of the work and to demonstrate theoretical background in the second language. In the study, 116 masters’ students of four different masters’ courses (radio electronics, environmental safety, technological machinery and design) were asked to complete a survey concerning the topic, purpose and theoretical foundations of their future thesis. As a result of written statements analysis, it was revealed that despite numerous grammar mistakes (word order, use of grammar tenses, etc.) and spelling, the majority of students are able to formulate the topic of their work. 76% of test persons can clearly formulate the objectives of their work in the second language, while a quarter of the students confuse it with the object or the result of the study. Only 3% of students can explain in English which theories and scientific works are used in their research projects. That is why an integrated approach to teaching English is needed to improve the ability of masters’ students to produce professional speech for future successful communication in their professional field.

Keywords: Academic skills, academic mobility, competences, motivation, professional communication, speech production

Introduction

In the today’s global world, scientific communication is hardly possible without English proficiency. Drubin and Kellogg (2012) mention that by learning a single language, scientists around the world gain access to the vast scientific literature and can communicate with other scientists anywhere in the world. Though it creates challenges for those whose first language is not English, proper motivation and learning can lead to significant outcomes resulting in successful scientific communication at the conferences, symposia, publication of papers, monographs and patents (Aizikovitsh-Udi & Amit, 2011; Butakova, 2016; Hubackova & Semradova, 2013; Tsyguleva et al., 2019). For this reason, continuous English study is important not only for bachelor students, but it is vital for master students who develop their academic skills and are involved into scientific studies (Fedorova et al., 2018; Ruchina et al., 2015; Tonkikh & Butakova, 2016). Moreover, one of the contemporary problems the students face with is transferring the emotional and expressive component of the term meaning when translating (Churilova et al., 2020). In order not to be isolated from global scientific community, they have to communicate both orally and in a written form in English. They should be able to discuss and share their findings, explain ideas, objective, theoretical importance and practical value of the work they perform during their study at master’s courses.

Problem Statement

The first challenge master students in Russia face is a two-year gap in studying English as the second language course finishes two years before the graduation from bachelor study and entering master courses. The lack of practice during this period results in deteriorating English communicative skills. General vocabulary, active grammar, speaking and writing skills worsen significantly although the desired level should be not less than upper-intermediate. In fact, only a small percentage of students manage to keep the level they obtained at bachelor courses.

The second problem is that master students do not have enough opportunity for general English skills revision and have to proceed with academic English. After two semesters they have to demonstrate strong skills in academic reading and writing (scientific papers, correspondence, patents), though some of them are unaware of basic grammar and vocabulary.

The next point to be considered is motivation. As many students are not involved into academic life of their university, do not take part in the conferences and demonstrate low academic mobility, they have low motivation to learn and perfect their English. This is true not only for master students but for most of Russian population (EF English Proficiency Index, 2021).

Research Questions

We conducted a survey among 116 master’s students of Omsk State Technical University. We chose four master’s courses: radio electronics, environmental safety, technological machinery and design. The age of students ranges from 20 to 37 years old and they have a gap in learning English from 2 years to 19, correspondingly. All of them have one English class a week during two semesters with a focus on academic English. Their study mainly includes reading scientific articles and grammar revision. The survey was carried out after one year of master course that corresponds to the end of the English course. The students have one more year left for their scientific work but a general scheme for their future thesis is usually clear for them.

Purpose of the Study

The objective of the paper is to find out the level of readiness to produce utterances in English in the professional context concerning master’s scientific work, to analyse the ability to explain the objective of the work and to demonstrate theoretical background in the second language.

Research Methods

The experiment proposes three questions connected with their scientific work, such as: What is the title of your thesis? What is the objective of the thesis? What theories, scientific works and achievements are used in your thesis? The students were given 10 minutes to respond without consulting dictionaries or other sources of information. The majority of responses includes grammar mistakes in word order, verbal concord, tenses use, spelling and total distortion of meaning (Table 1) though many students managed to produce clear and complex utterances demonstrating their ability to discuss their scientific works. We keep grammar and spelling mistakes as they are in students’ responses.

Findings

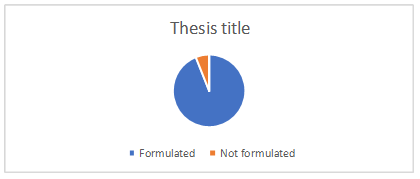

As the results show, for most students it is not difficult to formulate the title of their work as they have already started for one year at master’s courses and have weekly consultations with their scientific advisors. Only 6% are unable to articulate the name of the thesis (Figure 01)

The students produce complete sentences or give only the title. Just few are unable to formulate the title and name it as(Table 2).

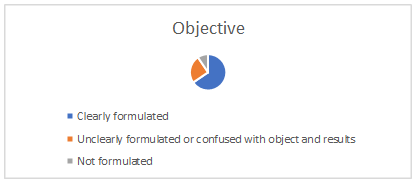

To identify the objective is a slightly more different task as some students (34%) confuse objectives with objects or results or are unable to formulate it at all (Figure 2).

The test persons point out objects () or results () as an objective. Also, we can see that for some students their objective is academically correct (). Those who managed to formulate their objective used complete and meaningful English sentences (Table 3).

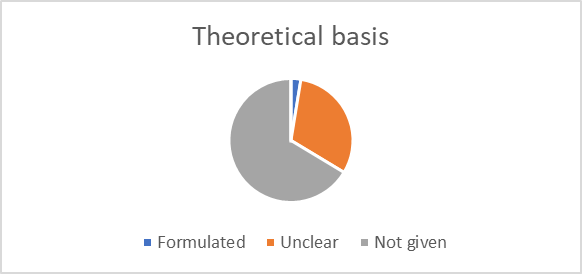

The most problematic question concerns theories and scientific works used in the thesis. For most test persons scientific basis is unclear, and they are unaware of the scientific ground they are constructing their work on. Only 3% were able to produce information on the question (Figure 3).

Students, with few exceptions, are unable to formulate the name of scientists and research area they are working in (Table 4).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can observe that most of master’s students have difficulties with both general English and academic English, but their mistakes usually do not fatally effect understanding. It is also clear that most test persons understand what scientific project they are working on and can explain that to the others, but scientific ground is still a challenge for them.

In order to solve the problems, we can propose to:

1. devote more time and energy to speech production in the form of scientific reports, papers, discussions and round tables;

2. collaborate with scientific advisors to help students with realizing goals and objectives of their works;

3. involve students in international scientific conferences and promote academic mobility in order to share the results, learn other scientific works and boost academic motivation;

4. use on-line technologies to train students on the basis of native speakers’ language utterances.

References

Aizikovitsh-Udi, E., & Amit, M. (2011). Developing the skills of critical and creative thinking by probability teaching. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 1087-1091.

Butakova, L. O. (2016). Language ability and speech competence of schoolchildren: analysis of cognitive mechanisms development. Bulletin of Volgograd State University Series 2: Linguistics, 15(4), 40-52. https://l.jvolsu.com/index.php/en/component/attachments/download/1484

Churilova, I., Fedorova, M., & Vinnikova T. (2020). Representation of theatre metaphors in the English linguistic worldview. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 99, 196-206.

Drubin, D. G., & Kellogg D. R. (2012). English as the universal language of science: opportunities and challenges. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 23(8), 1399.

EF English Proficiency Index (2021). Retrieved on May 2021 from: https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/regions/europe/russia/

Fedorova, M. A., Tsyguleva, M. V., Vinnikova, T. A., & Kirnosov, V. Y. (2018). Mathematical model of successful research activities for technical university students. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1141, 012012.

Hubackova, S., & Semradova I. (2013). Some specifics of foreign language teaching. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 1090-1094.

Ruchina, A. V., Kuimova, M. V., Polyushko, D. A., Sentsov, A. E., & Zhang, Xue Jin. (2015). The Role of Research Work in the Training of Master Students Studying at Technical University. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 215, 98-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.580

Tonkikh, T. A., & Butakova L. O. (2016). The formation of language ability and language competence in a situation of educational bilingualism. Intercultural communication: theory and practice of training and translation. Materials of V International scientific and methodical conference (pp. 294-299).

Tsyguleva, M. V., Tsoupikova, H. V., Fedorova, M. A., & Efimenko, I. N. (2019). Application of speech activity theories to the process of teaching humanities. In J. Kacprzyk (Ed.), Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing (pp. 426-433). Springer.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

02 December 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-117-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

118

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-954

Subjects

Linguistics, cognitive linguistics, education technology, linguistic conceptology, translation

Cite this article as:

Fedorova, M., Vinnikova, T., & Churilova, I. (2021). Students’ Readiness For Speech Production In The Second Language. In O. Kolmakova, O. Boginskaya, & S. Grichin (Eds.), Language and Technology in the Interdisciplinary Paradigm, vol 118. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 594-600). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.73