Abstract

This paper argues for the need to promote active citizenship and activist pedagogy (ACAP) in the public education system. Additionally, a program to train in-service teachers to promote ACAP is required in order to foster ACAP among students inside classrooms and outside (e.g., breaks, sports lessons, volunteering etc.). Teachers need a practical model that will help them implement this approach. This article combines a conceptual evaluation, developing training program and practical model components and crosses three different areas: (1) Explaining the concept of activist pedagogy as a contemporary pedagogy. It shows the need to invest in activist teachers promoting ACAP for the 21st century progress. (2) Showing the need to develop an outline for an ACAP training program for high school teachers. (3) Delineates the key problems resulting from an absence of practical tools for activist teachers and presents a proposed new five level practical model to address this phenomenon.

Keywords: Active citizenshipactivist pedagogyactivist teachersteachers' training programa practical model to promote ACAP

Introduction

In recent decades, educational scholars such as Eisenberg and Selivansky (2019) have shown that the pedagogical basis schools provide to students are based on the same skills needed during the Industrial Revolution. Different skills are required in the 21st century; the Organisation for Economic, Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2018) reported that students need to learn how to contribute to their own well-being, communities and the whole planet; how to set goals and act responsibility; make changes and act rather than be activated. In addition, Dede (2010) wrote a comparative framework for skills, and those associated with ACAP are social and civic engagement responsibility and global awareness. Therefore, the importance of integrating active citizenship into school education is essential in a 21st century context to educate humanist values and preserve democracy.

There is a huge need for pedagogies educating towards active citizenship and political activities in schools (Nelson & Kerr, 2006). Studies have shown that young adult and youth behaviour is apathetic and not only do they know less about public affairs but also their involvement in and even voting for government is on the decrease (Astuti, 2019). Educational programs are needed to promote active citizenship, activism, civic engagement and to preserve endangered democracy in a global and multicultural era (Veugelers, 2019).

A rising tendency is one of critical education, where knowledge is provided a dialogue between students and teachers, allowing critical assessment and wider perception of the information and not of oppression (Freire, 2018). Thus, to create equitable, pluralistic and genuine teaching, it is necessary to embrace a commitment to allow members of a community to participate actively and continuously in the creation of meaning, knowledge and values (Apple & Apple, 2018). A positive correlation was found between ACAP studies, engagement in social justice and future involvement in public activity and high education (Johnson et al., 1998).

There is a need for more professional activist teachers to promote ACAP and teach students to take further, practical steps towards changing society. According to Sachs (2003), this form of teaching is not only possible, but necessary for defining teaching as a profession. Niblett (2015), examined narratives of activist teachers' in Canada. The researcher explained integrating activism in public schools is justified, including the global situation, disasters threatening the whole of mankind, demanding interventions, as well as maintaining democracy for humanity's existence. He emphasized that activist pedagogy is not about educating subversive protests, but about caring education to change injustices that are in the immediate environments.

Indeed, education scholars cannot remain passive. This paper focuses on promoting ACAP as well as the need to develop an ACAP training program for teachers. A program that will train in-service high school teachers must give them practical tools to implement an ACAP approach inside classrooms and outside (meaning in breaks, sports lessons, being active in the community, volunteering, an annual school trip, etc.).

Problem Statement

The changes in the current social reality and educational reality suggest the idea of necessity to promote ACAP through education. As far as we know today, there is no practical training that includes a practical model for learning ACAP inside and outside classrooms for high school teacher.

Research Questions

This article does not present research questions because this is an exploratory research in which we seek to examine educational processes/phenomena, in order to build a coherent and comprehensive global image. Most often, exploratory research lays the groundwork for future research, so it is a preliminary investigative sequence that precedes systematic scientific research. However, through the results, exploratory research can be independent research, which leads to a better understanding of the studied phenomena and a clarification of the problems, facilitating the testing of hypotheses in future research.

Purpose of the Study

To explore the need for activist pedagogy and active citizenship, to develop activist teachers, and to implement this approach inside and outside classrooms. From examining the research literature and from the experience in education of the authors, we saw the need for an ACAP teacher training program that will provide teachers with a practical tool for imparting ACAP content inside and outside classrooms.

Research Methods

This article entails theoretical research. The main research method was represented by thematic analysis, through which we envisaged to construct a theoretical-explanatory vision to render a possible explanation for ACAP. There is a practical need to develop high school teachers' training and a practical model to promote ACAP.

Findings

The findings combine a conceptual evaluation, developing training program components and a practical model and crosses the following areas:

The Importance of Promoting Active Citizenship Through Education

According to Kennedy (2006), the concept 'active citizenship' moves on a spectrum between active and passive, from passively active citizenship to actively passive citizenship. Actively active citizenship, refers more to the contexts of “doing” and passively active citizenship, refers more to “being”. Cultural, social and political contexts can be influencing factors in active or passive access to active citizenship. Being active as a citizen, according to Kennedy (2006), means taking part in political citizenship, civic social movements, citizens promoting social change, national identity, patriotism and even a loyal citizenship. Kennedy (2006) proposed a division as described, arguing that the more active citizenship active citizens, will promote greater social change.

Therefore, according to Kennedy (2006) and Nelson and Kerr (2006) who conducted comparative research in sixteen countries about active citizenship education, each country has its own typical reasons for developing active citizenship through education. Some may promote obedience, social duty and hard work as active citizenship, while others seek to develop values for all citizens, who will support society through these values, and some teach future citizen to think independently and critically. According to Nelson and Kerr (2006) countries interpret their social, political situation and promote their key messages through the term "active citizenship". Sometimes the state will accept the challenge and will try to address social involvement through active citizenship education. Lawson (2001) defined active citizenship in general as a relationship between rights and obligations. According to her, the main element of citizenship is the idea of participating actively in public life. However, the phenomenon of inactivity in the context of citizenship can be directly reflected in education.

At first, active citizenship studies were only associated with history studies, teaching knowledge and civil structures of home countries (Kerr, 1999). Later, according to Bron (2005), three categories were defined, linking components of education to active citizenship. The first - core values related to human rights and social responsibility. The second - law-based values such as: values of democracy, fundamental laws of freedom and the third - humanistic values such as tolerance and empathy. In order to develop the younger generation, emphasis should be placed on skills and competences such as: action, inquiry, engagement, and accountability through action. There is also knowledge and understanding of the role of law, democracy and government, economics and society and naturally, the environment. And finally, to develop creativity and entrepreneurship to help the younger generation and teachers have ambition and aspirations for the future as well as looking at their learning and life goals. These may be the components of active citizenship education.

Despite the findings of the Bron (2005) study, the final report comparing 15 countries) Nelson & Kerr, 2006) shows that there are countries that do not emphasize the values of the above three categories and highlights the key issues of knowledge and understanding of state institutions, obligations and government. This illustrates the need to train teachers how to implement actions that promote active citizenship as suggested by researchers like Bron (2005) and Sachs (2003; 2016).

In light of the above, active citizenship education differs from one country to another, but we can state that the idea of active citizenship generally refers to challenging the existing order and the status quo. Compared to the passive part of active citizenship which works to preserve the existing order and the status quo. The role of education, therefore, is to develop students' awareness of issues related to promoting social change, encouraging their partnership and involvement as active citizens. But to educate, teachers must be trained to do so. If active citizenship is on a spectrum between passive and active at its two poles, emphasizing and addressing its active side in the educational aspect is our next focus.

Activist Pedagogy

The educational system in many western countries promote knowledge, values and cultural hierarchies which reflecting interests of groups that control society. Seemingly, these countries, and many others, are leading a human-wide worldview and striving for a democratic and new social order (Aloni, 2005). However, mass teacher mobilization is required to recalibrate the debate on what schools, students, and communities need (Picower, 2012). Giroux (2001) claimed that schools exist to spread conservative traditions, using temptations, pressure and threats (grades, exams) to force students to accept “despicable, irrelevant” material. Thus, the ability to understand complex messages and critical thinking become irrelevant. Reflective abilities are pushed aside, as impractical or lacking purpose, according to messages passed by teachers, who represent a hegemonic system. Therefore, the need to develop contemporary pedagogy is great.

Activist pedagogy is the antithesis of the old, hierarchic, normalizing traditional methods of pedagogies. In order to understand it, there is a need to understand progressive pedagogy theory (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1993) and radical critical pedagogy (Apple & Apple, 2018; Freire, 2018; Giroux 2001). Critical theory seeks to decrease the power given to educational texts and contexts demanding critical dialogue between teachers and students about them. According to critical theories it is necessary to empower students and their ability for self-fulfilments. The critical pedagogy guides the students towards personal autonomy, independency and liberalization (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1993).

Researchers like Frey and Palmer (2014) claimed that activist pedagogy is a concept that is meant to develop implementation of critical theories. They wrote that activist pedagogy is “putting meat on critical pedagogy’s theoretical bones” (p. 26). Freire's (2018) response was that his critical pedagogy was lacking in practical experience because he did not want to frame one practical pedagogy but to reinvent it. Perhaps the development of activist pedagogy stemmed from a sense that something was missing from the practical part of Freire's critical pedagogy. Or perhaps in light of what Ollis (2012) claimed in her article on activism, reflection and Freire - embodied pedagogy, which referred to the term used in his book on oppressed pedagogy "naive activism" (Freire, as cited in Ollis, 2012) as his way of calling for the continuation of critical pedagogy to develop into activist pedagogy.

It is now time to evaluate the concept of activist pedagogy and consider its definition in current literature. Activism is usually defined as an action aimed at promoting ideas to change a particular reality. This action takes place in a social, public and community context and mostly works against various oppressive forces (Misgav, 2015). Activist teachers are those who participate in social justice activities or teachers who try to promote awareness and ACAP because of ideological belief in social change for a better world (Catone, 2017; Marshall & Anderson, 2008; Sachs, 2003).

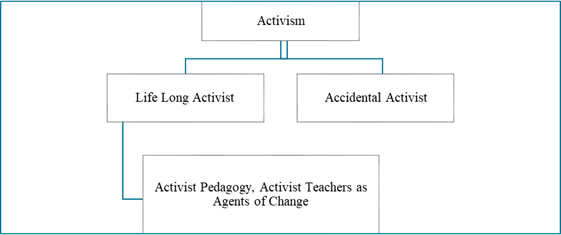

According to Ollis (2012), there are two factors which result in activism. One is circumstantial and the other is a sense of purpose. Its distinction is important because it can help understand the context of activist pedagogy. Motives for activism, she argued, can be linked to activists' long-term sense of purpose or a motive that accidentally happened by necessity. Those whose sense of purpose guides their activities as activists are holistically driven with emotion and passion. Whereas those who avoid accidental circumstances, for the purpose, solve a complex problem encountered and understand that activist tactics will correct and resolve it. Long-term activists are those who are connected to activist teachers and activist pedagogy. Ollis division of activism can be seen is Figure

In order to understand the specific terminology of activist pedagogy, one needs to understand the pattern in which studies relate to undermining the status quo, promoting social justice and anti-oppression through the act of education. Some scholars, like Kostiner (2003), Marshall and Anderson (2008) and Kelchtermans (2007), tended to see the changes in education in political contexts and through two terms that relate to politics, micro-politics and macro-politics. These are related to the analysis of political processes in the education system and schools. Macro-politics can refer to the forces of teacher collaboration, parents and community influencing educational decision-making processes at regional and national levels. Many such activists are called educational justice activists (Kostiner, 2003). Micro-politics refers to teachers and informal groups within schools seeking to achieve their goals for change (Kelchtermans, 2007; Marshall & Anderson, 2008).

In reference to this, activist pedagogy in the micro-political context speaks to more internal functions in the field of education in schools (Catone, 2017; Marshall & Anderson, 2008; Sachs, 2003). Engagement in activist pedagogy is therefore a more holistic way of promoting social justice, human rights, stereotypes, gender identities, racism prevention and in general raise awareness of human rights and social change for local, and even, global equality inside and outside classrooms.

Kostiner (2003) from the University of California, Berkeley, examined 25 activists for educational justice using in-depth interviews and found three main schemas: instrumental, political and cultural schema.

The instrumental schema describes activists who promote equality in resources, funding for poor schools, materials lacking in education systems and are, according to this schema the explanation for change in educational injustice.

The political schema describes the state of power relations highlighting unequal power structures. Governments have been proven to act as oppressors. Thus, activism for the change in education focuses here on struggles against government. Tactics used in these two schemas are similar to those used by legal counsel (Perry-Hazan, 2015).

The cultural schema differs from the previous two concepts of activist pedagogy in that it refers to a conscious, internal change in assimilating reforms. It uses educational cultural activists through changes in consciousness, conceptual change, and in fact, it believes that education to change is rooted in assumptions that dominate reality. Tactics used for cultural schema could be the activist teachers as agents of social change and promoting ACAP.

This distinction between three contexts shows different ways of working toward reforms and educational changes that will bring about social change. These are important to understanding the differences in the analysis of activist pedagogy. These concepts of macro and micro politics and the aforementioned three schemas can help us understand the position of activist teachers in the context of activist pedagogy - it refers to micro politics and schema of culture.

The next section will focus on activist teachers a term arising from activist pedagogy (Catone 2017; Marshall & Anderson 2008; Sachs 2003) and the need to train teachers to fulfil professionally their designation as social agents, to change the world through education.

The need for Training Programs to Develop Activist Teachers

Activist teaching embedding activist values and active citizenship inside and outside classrooms, will be those who can be relied upon to take responsibility for correcting reality, fulfilling its internal designation as long-life activism. Teachers have significant potential to bring about change in the community through their students. As studies have shown, teachers influence students' lives, can change their conceptions, awareness, consciousness and behavior (Catone, 2017; Fullan, 1993; Marshall & Anderson, 2008; Ollis, 2012; Perumal 2016; Sachs, 2003). Freire (2018) urged teachers to go beyond the depressed and irrelevant state of educational systems, dare to fight for a better and more just society. Thus, society begins with individual person-to-person encounters, filled with confidence, hope and daring to dream of change.

Giroux (2001) called for an increase in the number of 'intellectual teachers' lead change in a conservative, hegemonic system of education. McDermott (2017) pointed out that critical pedagogy compels teachers and their students to explore relationships in larger historical, global, economic and social constructs as they relate to local and global conditions of being active. Montaño et al. (2002), studied a group of five activist teachers involved in social and political organizations in Los Angeles, and examined the relationships between their social activism and being teachers and whether it reflects on their classrooms practice. Part of what they found was that their activist pedagogy practice was deficient.

Sachs’s book (2003) specifically described the roles of teachers. In general, her writings see the need for a transition of the teaching' profession from conservative pedagogy to activist contemporary pedagogy. She referred to changes she had observed in teachers in Western countries (UK, Australia, Singapore, and United States) in light of the external and internal changes that have occurred According to this, the teaching profession can be reframed into five elements contributing to the change: learning, participation, collaboration, cooperation and activism.

More than a decade later, Sachs (2016) asked why the teaching profession still had not changed. In 2016, teachers were expected still to be objective and neutral, trying to stifle conflicts, and perhaps finding a unified and diverse pedagogy in education by focusing on regulation, which meant that teachers remain mindless performers only.

However, being an activist teacher is not easy. Some might consider education and activism mutually exclusive, even if activism is relevant to school issues such as racism, sexual harassment or sexism. A study conducted in North Carolina, USA among 52 teachers showed a narrative of keeping a low profile among activists in a school environment, with public activism very limited. Activist teachers felt alone, isolated, and forced to keep quiet in a hegemonic education system (Marshall & Anderson, 2008). This is harmful, because teachers can be socially active on issues and activities not taking place in schools directly, as described by Catone (2017), with teachers being active in communities and forums for human rights.

Hence, in light of the above, we show that the ability to promote activist educational goals and approaches is found in teachers who embody activist pedagogy in teaching. It is therefore understood that teachers who want to implement an activist approach in their teaching require training, support and, of course, practical tools to integrate an activist approach in teaching. Another requirement is teachers working collaboratively. It is our belief that through a training program for a group of in-service teachers who are interested in learning the activist approach so as to develop themselves as activist teachers, a community of practice will be created, which will help them not to feel alone in their campaigns, nor should they experience professional loneliness, as described by Marshall and Anderson (2008).

The need for future development of high school teachers' training program to promote ACAP

Throughout this article, we have shown the need or ACAP, and for that purpose, we have shown the need for developing a teacher training program, so that they can learn how to teach in an activist approach. Developing a training program should take into consideration not only knowledge and theoretical matters of ACAP education, but practical tools to help teachers actively promote ACAP. It should also consider, as shown in previous sections, how to change teachers’ attitudes, to understand the need for courage when implementing activist pedagogy in schools, and perhaps engage them to belong to communities of practice.

Brown (2006), in her research, in the context of preparation programs, examined forty graduate students in black in awareness of, acknowledgement of, and action toward social justice. It is one example of many (Marshall & Anderson 2008; Sachs 2003; 2016) demonstrating the possibilities and power of helping promote teachers to foster activist pedagogy inside and outside classrooms.

A number of issues should be addressed when developing a teacher training program in ACAP, have emerged from the research literature analyzing courses taught by teachers and lecturers with activist approaches such as Lash and Kroeger (2018), Luguetti and Oliver (2019), Sundvall and Fredlund (2017), Zalmanson-Levi (2015). These issues indicate the main areas which an initial framework of an activist teacher training program should address - knowledge, attitudes, and practical methods for teachers about topics making up activist education.

So far, we have shown the great need to develop a teacher training program for the promotion of ACAP. Developing such a program is a topic of a future article. As mentioned, one of the important aspects of such a training program is the one teaching the practice to teaching ACAP in and outside classrooms. The next section, which concludes this article will depict the development of this model, which is one aspect of a system of components to be developed further to the high school teachers' training program to promote ACAP.

Developing a practical model to be taught in the framework of teacher education to promote ACAP

Developing a practical model could help teachers integrate an activist approach in their subject matters. High school teachers who have been trained for ACAP will want to be able to promote it inside and outside of their classrooms. They will need to get tools that will help them do so. A model based on an analysis of studies about ACAP, new studies (see below) and experience of the authors in education, developed. The aim of this practical model, as part of an ACAP training program, is to give tools to teachers participating in the training program, so that they can implement activist approaches in their teaching inside and outside classrooms.

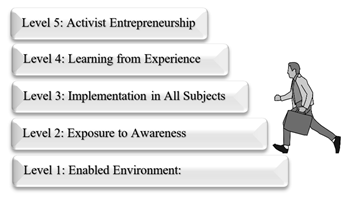

The proposed practical model takes into consideration diverse possibilities available to teachers to promote activism in teaching. That is why it has been divided into five advancing levels. Teachers can choose how long to focus on each level and whether to go further. On the other hand, teachers do not have to advance to further levels, although it is recommended to implement all levels.

The first level is considerably basic and extremely important, a learning environment to enable activism and active citizenship. It is about visibility, to create a supportive and progressive environment allowing students to be present and grow. An environment in which anything can be discuses without harming anyone else, to criticize without regret and a space that promotes change. For example, language teachers employ inside, and outside classrooms is part of an environment that enables activism. Sarroub and Quadros (2015) examined how language affected students’ immediate reality and their communities and pointed out how it produced discourse and cultural awareness. Some critical and activist pedagogy researchers also addressed the meaning of creating an educational environment that promotes independent thought and how to explore ideas that could educate the young generation to learn how create social justice changes (Harpaz, 2008; Kumashiro 2015; Niblett, 2015).

The second level is exposure to and raising awareness of activist discourse and agenda as a supplement lessons in all subjects. Peer groups are a major factor teacher encounter in everyday formal settings in schools, and serve as a source of experiential social belonging, thus can be used as modelling for students as an influential factor promoting their identities as future citizens (Lawson, 2001). This modelling can be demonstrated to students by sharing current affairs concerning teachers. Or teachers can raise issues with the purpose of raising students’ awareness. No more than ten minutes of lesson time is needed.

The third level is the ACAP implementation level, incorporating an activist agenda into the teaching profession. Freire (2018) emphasized the importance of dialogue and educator-students' interaction teaching. Dialogue on issues that emerge from the curriculum connecting to moral values during lessons adds to socio-political affinity. A learning strategy in critical pedagogy is strengthens processes that explain to students' rights and obligations that can be connected to lesson subjects. It is an opportunity to take a different look at reality and any injustices around them. When students, together with teachers, see this as part of teaching with teachers asking questions, and challenging the status quo, there is a sense of liberation, having the ability to influence and possibly make change (Bahruth & Steiner, 2000; McDermott 2017). Zalmanson-Levi (2015) addressed how teaching mathematics was a chance to promote equality.

The fourth level is learning from experience. Teachers can search for opportunities to encourage, together with students, experiences of activist, meaningful activities associated with teachers' agenda in schools. This could be experiencing and learning about democracy at school. Some schools have service communities, which could serve as opportunities for finding ways to talk about and learn from their experiences making change (Frey & Palmer, 2014). Some studies have examined ways of learning from experience as an activist approach such as Catone (2017), Luguetti and Oliver (2019), Picower (2012), Zalmanson-Levi (2018; 2019).

The fifth level is activist entrepreneurship. Initiatives in collaboration with students to devise projects promoting activist activities according to teachers’ agenda, in or outside schools. An example of learning from the fifth level can be found in Sundvall and Fredlund’s (2017) interesting review of their courses at the University examining their activist approach by asking students to create activist entrepreneurship initiatives. One group produced a parade on the issue of violence, while another created a website showing activist activities against the use of animal fur. Chryssochoou and Barrett (2017) showed students from a younger generation using technology to become involved in a social network which can also be a space in which initiatives can take place. Teachers who complete the fifth level by creating space for initiatives outside schools that promote change and challenge the status quo are brave and must comply with school regulations, procedures and instructions and only act within their scope. These activist teachers will also experience a real dialogue between themselves and students when the depressing barriers usually disappear.

Figure

The skills taken into consideration when developing this practical model for promoting ACAP as one of the key parts of an ACAP training program are reminiscent of skills discussed at the beginning of this article as required according to OECD (2018). From exploring the ACAP related themes in the research literature, and from the authors' experience a proposal is presented for a practical solution to the problem of the necessity to promote ACAP through education. The five-level model developed for implementing ACAP inside and outside classrooms can be a practical tool for fostering ACAP in teaching and constitute grounds for future research. High school teachers will acquire it in the training program as a tool to develop skills and practical implementation of ACAP education.

Conclusion

This paper was written at a time when education must be part of ethical and moral thinking for the future of the younger generation. To face increasing 21st century challenges, the younger generation must be educated in critical social activism paradigm. Despite all the difficulties implementing activist pedagogy, it is the way to educate the younger generation to behave as human beings and become significantly active citizens. This article concludes it is more than useful to develop a teacher training program including practical tools for teachers to promote ACAP. The five-level practical model for implementing ACAP inside and outside classrooms, helps teachers promote activist approaches in teaching, at different levels reflecting teachers’ place and level of readiness to implement them in their teaching. The five-level practical model for implanting ACAP and the training program for ACAP will be examined in PhD research conducted by author (a) there appears to be a need to write a follow-up article that will elaborate on teacher training to promote ACAP that will attitude and knowledge about ACAP in addition to practical tools. Considering this study’s findings, the proposed five-level practical model to promote ACAP inside and outside classrooms, may provide tools for teacher development and for education systems to promote greater student engagement in society, community, and as future citizens.

References

- Adorno, T., & Horkheimer, M. (1993). Ascolot Frankfurt (mivhar) [Frankfurt teachings (selected)]. Bney Brak: Sifriyat HaPoalim.

- Aloni, N. (2005). Kol ma shetzarich kdei lehijot adam. Masa befilosofiya hinuchit, antologiya [All that one needs to be a human. A journey in educative philosophy, anthology]. HaKibutz Hameuhad ve-Mahcon Mofet.

- Apple, M., & Apple, M. W. (2018). Ideology and curriculum. Routledge.

- Astuti, S. I. (2019). Enhancing Active Citizenship and Political Literacy among Young Voters in High School. In Social and Humaniora Research Symposium (SoRes 2018) (pp. 309-313). Atlantis Press. DOI:

- Bahruth, R., & Steiner, R. (2000). Upstream in the mainstream: Pedagogy against the current. In S. Steiner, M. Krank, P. McLaren, & R. Bahruth (Eds), Freirean pedagogy, praxis, and possibilities: Projects for the new millennium (pp. 22- 1). Falmer Press.

- Bron, J. (2005). Citizenship and social integration. Educational development between autonomy and accountability. Different faces of Citizenship. Development of citizenship education in European countries (pp. 51-70). CIDREE/DVO.

- Brown, K. M. (2006). Leadership for social justice and equity: Evaluating a transformative framework and andragogy. Educational administration quarterly, 42(5), 700-745.

- Catone, K. (2017). The pedagogy of teacher activism: Portraits of four teachers for justice. Peter Lang.

- Chryssochoou, X., & Barrett, M. (2017). Civic and political engagement in youth. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 225, 291-301. DOI:

- Dede, C. (2010). Comparing frameworks for 21st century skills. 21st century skills: Rethinking how students learn, 20, 51-76.

- Eisenberg, E., & Selivansky, O. (2019). Adapting the education system to the 21st century [Hat’amat maarechet ha-hinuch lamea ha-21]. Israeli Democracy Institute.

- Freire, P. (1970/2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed. 50th Anniversary Edition. Bloomsbury publishing USA.

- Frey, L. R., & Palmer, D. L. (2014). Introduction: Teaching communication activism. Teaching communication activism: Communication education for social justice, 1-42.

- Fullan, M. G. (1993). Why teachers must become change agents. Educational leadership, 50, 12-12.

- Giroux, H. A. (2001). Theory and resistance in education: Towards a pedagogy for the opposition. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Harpaz, Y. (2008). Keizad letachnen sviva hinuchit beshisha tzeadim- hamadrich [How to plan an educational environment in six steps- the guide]. Hakibbutz Hameuhad.

- Johnson, M. K., Beebe, T., Mortimer, J. T., & Snyder, M. (1998). Volunteerism in adolescence: A process perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8(3), 309-332.

- Kelchtermans, G. (2007). Macropolitics caught up in micropolitics: The case of the policy on quality control in Flanders (Belgium). Journal of Education Policy, 22(4), 471-491.

- Kennedy, K. (2006). Towards a conceptual framework for understanding active and passive citizenship. Unpublished report.

- Kerr, D. (1999). Citizenship education: An international comparison (pp. 1-31). Qualifications and Curriculum Authority.

- Kostiner, I. (2003). Evaluating legality: toward a cultural approach to the study of law and social change. Law & Society Review, 37(2), 323-368.

- Kumashiro, K. K. (2015). Against common sense: Teaching and learning toward social justice. Routledge.

- Lash, M. J., & Kroeger, J. (2018). Seeking justice through social action projects: Preparing teachers to be social actors in local and global problems. Policy Futures in Education, 16(6), 691-708.

- Lawson, H. (2001). Active citizenship in schools and the community. Curriculum Journal, 12(2), 163-178.

- Luguetti, C., & Oliver, K. L. (2019). ‘I became a teacher that respects the kids’ voices’: challenges and facilitators pre-service teachers faced in learning an activist approach. Sport, Education and Society, 1-13.

- Marshall, C., & Anderson, A. L. (Eds.). (2008). Activist educators: Breaking past limits. Routledge.

- McDermott, V. (2017). We must say no to the status quo: Educators as allies in the battle for social justice. Corwin Press.

- Misgav, H. (2015). Activist, zehut vemerchav beIsrael/Palestin, shalosh nekudot mabat [Activism, identity and space in Israel/Palesitne, three perspectives]. Teorija veBikoret, 45, 217-232.

- Montaño, T., López-Torres, L., DeLissovoy, N., Pacheco, M., & Stillman, J. (2002). Teachers as activists: Teacher development and alternate sites of learning. Equity & Excellence in Education, 35(3), 265-275.

- Nelson, J., & Kerr, D. (2006). Active citizenship in INCA countries: Definitions, policies, practices, and outcomes. NFER/QCA.

- Niblett, B. (2015). Narrating activist education: teachers' stories of affecting social and political change (Doctoral dissertation).

- Ollis, T. (2012). A critical pedagogy of embodied education: learning to become an activist. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Organisation for Economic, Co-operation and Development. (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030.

- Perry-Hazan, L. (2015). Court-led educational reforms in political third rails: Lessons from the litigation over ultra-religious Jewish schools in Israel. Journal of Education Policy, 30(5), 713-746.

- Perumal, J. (2016). Enacting critical pedagogy in an emerging South African democracy: Narratives of pleasure and pain. Education and Urban Society, 48(8), 743-766.

- Picower, B. (2012). TEACHER ACTIVISM: Social Justice Education as a Strategy for Change. In Practice What You Teach (pp. 17-32). Routledge.

- Sachs, J. (2003). The activist teaching profession. Open University Press.

- Sachs, J. (2016). Teacher professionalism: Why are we still talking about it? Teachers and Teaching, 22(4), 413-425.

- Sarroub, L. K., & Quadros, S. (2015). Critical pedagogy in classroom discourse.

- Sarroub, L. K., & Quadros, S. (2015). Critical pedagogy in classroom discourse. In M. Bigelow, & J. Ennser-Kananen (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of educational linguistics (pp. 252-260). Routledge.

- Sundvall, S., & Fredlund, K. (2017). The Writing on the Wall: Activist Rhetorics, Public Writing, and Responsible Pedagogy. In Composition Forum (Vol. 36). Association of Teachers of Advanced Composition.

- Veugelers, W. (2019). Education for Democratic Intercultural Citizenship (EDIC). In Education for Democratic Intercultural Citizenship (pp. 1-13). Brill Sense.

- Zalmanson-Levi, G. (2015). Y=X: horaat matematika kehizdamnut leerech shivjoh [Y=X: teaching mathematics as a chance for the equality value]. In N. Rivlin (Ed.), Shiur Lahaim- hinuch neged gizanut mehagan vead hatichon (pp. 55-72). Hasadna.

- Zalmanson-Levi, G. (2018). Nihul kita kemerchav leshinuj hevrati [Managing a classroom as a space for social change]. In I. Eliezer, & D. Gorev (Eds.), Nihul kita (pp. 265-285). Mofet.

- Zalmanson-Levi, G. (2019). Shinuj todaa- pedagogiyta bikortit feministit [A change of awareness- critical feminist pedagogy]. In M. Haskinm, & N. Avishar (Eds.), “Ziv notzetz medema” - sugiyat hamizrakhiyut beheksherim hinuchiim vetarbutiim (pp. 149-177). Resling.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 March 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-103-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

104

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-536

Subjects

Education, teacher, digital education, teacher education, childhood education, COVID-19, pandemic

Cite this article as:

Ayali, K. K., & Muşata, B. (2021). A Model to Promote Active Citizenship and Activist Pedagogy (ACAP) in High School Teaching. In I. Albulescu, & N. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2020, vol 104. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 10-22). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.03.02.2