Abstract

Inclusive public space is a place that easily accessible by all people, and no one feels excluded there. In 2014, Bandung City developed a thematic park concept in several park locations. City parks as public open spaces should be able to use by all groups, especially women, children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. The development of thematic parks changes facilities in the park and changes the characteristics of park users. Therefore, it is necessary to know the level of thematic park inclusiveness as an evaluation of the development of public spaces in the city of Bandung. This research identifies indicators and the level of inclusiveness of public open space in the city of Bandung. We conducted observational surveys and questionnaires at the thematic and public parks/squares and to determine the level of inclusiveness and public perception of the inclusiveness of the space. We measure various types of access and visitor characteristics. Based on the analysis of the inclusiveness level of public open spaces in Bandung, non-thematic parks are considered slightly more inclusive than thematic parks, but thematic parks have higher visit frequency. The slight difference in the level of inclusivity indicates that there is potential for the development of thematic parks to be more inclusive by improving physical access and activities.

Keywords: Public spaceinclusivityaccessibilityurban parkthematic park

Introduction

Inclusive Public Open Space

Public open space is one of the crucial aspects of people's lives in urban areas (Woolley, 2004). It is the place for the activities of urban communities to take place, whether intentional or not. It is a space that can be accessed by the community as a user of the area. The core of public space is where functional activities take place that brings together people both in daily activities and periodic activities (Carr et al., 1992). Open space is an arena that allows various types of events to include essential, optional and social events (Gehl, 2011). According to Charter of Public Space, (Garau, 2017), public spaces are places that are publicly owned or used for public use, can be accessed and enjoyed by everyone for free and without profit motives. The emphasis on access was stated by Langegger (2016) that open space is a locality that can be accessed by the public.

One dimension of public open space is the level of inclusiveness (Maftuhin, 2017; Mehta, 2014; UN Habitat, 2015). The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) place six out of 17 sustainable development goals discussing social inclusion. One of the goals explicitly outlined in the goal 11 of the SDGs is that by 2030, cities must provide public space and green open spaces that are safe, inclusive and easily accessible, especially for women and children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. Public space must be an accessible place that is created and managed through an inclusive process (Madanipour, 2010).

Thematic Park as A Public Open Space

Parks offer a variety of recreational opportunities for city dwellers, although much is more than just the recreation that takes place there. People use public parks on their way to other sites, just as they do on city streets. A more significant proportion of the area usually occupied by the park consists of green plants, and the park tends to provide good shelter from the surrounding city and contribute to its sustainability (Garvin, 2016).

A thematic park is a park designed by carrying unique themes/concepts as a distinctive place identity by bringing up special characters, so a specific impression of the park's function can be perceived when people see the park (BAPPEDA Kota Bandung, 2014). Providing thematic parks in the residential neighborhoods of the city of Bandung has been transformed into a park with a scale of city services. It has become a new public space that serves enjoyment for urban communities with enticing design and amenities (Ari et al., 2016). The main thing that distinguishes thematic parks from other parks is from the characteristics that stand out Ramadhani (2015). These characteristics are represented in its facilities. For example, at Photography Park in Bandung City, besides providing facilities for photography, there is also children's playground, so that the activities that can be done there are not limited to the particular theme. At Music Park in Bandung City, in addition to providing facilities for music, there is also a basketball court so that users can also exercise. Those city parks (Figure

Problem Statement

Decent access to public spaces for people of different age groups, genders, and physical abilities is an essential aspect of a sustainable and inclusive city (Subramanian & Jana, 2018). The development of thematic parks increases the social function of open spaces as a place for the community but limits the type of users. Specific thematic parks might appeal to only specific communities, so maybe there is a group of users that feel excluded from there. There is research on the characteristics of Bandung thematic park users that conclude that users in the thematic parks in Bandung City have different user characteristics because the only specific community that attracted the particular thematic park (Ilmiajayanti & Dewi, 2015). The development of thematic parks changes the facilities provided and is indicated to change the characteristics of park users so that it can reduce the level of space inclusiveness, so it is important to discuss the level of inclusiveness of public spaces that users characteristics and the facilities provided are different from public spaces in general.

Research Questions

Public open space should be formed so that it can be accessed and provide optimal social benefits for all citizens of the city. In this case, the square and city parks should be inclusive, which can be used by all, especially women, children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. The development of thematic parks changes the facilities provided and is indicated to change the characteristics of park users. The research questions are as follows:

What are the indicators of inclusiveness in public open spaces and how to measure them?

What are the characteristics and perceptions of public space users regarding the inclusiveness of public space?

What is the level of inclusiveness of public open spaces in the form of squares and thematic parks?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to identify the inclusiveness of thematic park as public open space in Bandung City by comparing it to non-thematic park. There are goals to be pursued:

Formulation of indicators of public open space inclusiveness in the Bandung City

The identification characteristics and perceptions of public space users about inclusive public open spaces

The identification of the level of inclusivity of public open spaces

This research provides insight into one part of the aspects in the realization of inclusive cities through improving public open space. The findings in this study are in line with the goal 11 of SDGs, which are inclusive and sustainable development. Practically, the results of the research can be input into efforts or strategies to increase the inclusiveness of public open spaces for the Government of the City of Bandung.

Research Methods

This research approach is quantitative, by making weights and comparisons that is related to the variables used in this study. The survey conducted was observation and questionnaire to find out physical condition and perception according to respondents. Descriptive statistics are carried out on the process of identifying the socio-economic characteristics of park visitors. Existing conditions are compared between thematic parks and squares.

Time and location of research

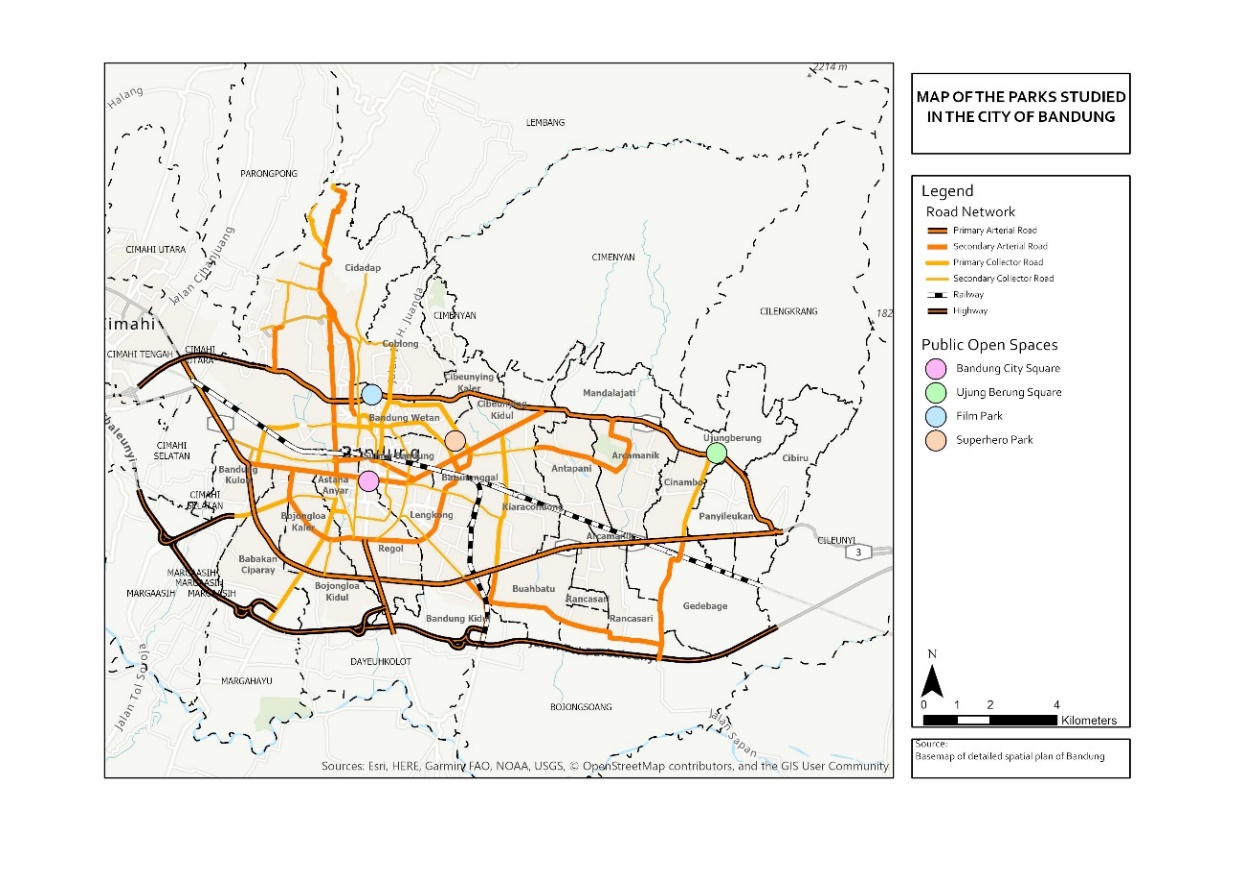

The city of Bandung was chosen as the study area because since 2014 it has developed the thematic park concept in several park locations. The object of research is public open space in the form of city-scale public parks and city-scale thematic parks, which are within the area of Bandung City. Field surveys were conducted in 2019. The public open spaces sampled were (1) Bandung City Square, (2) Ujung Berung Square, (3) Superhero Park, and (4) Film Park (Figure

We selected several parks that are determined by several criteria: used by the public, open, free of charge, and quite a lot of visitors throughout the week, both weekdays and weekends based on initial observations. The square is chosen as a comparison of thematic parks that are without a specific theme. Bandung City Square and Ujung Berung were selected because of their distant location and representations of a different district in the city.

Method of collecting data

We collect secondary data and primary data from April to May 2019 at designated public spaces. Secondary data collection is conducted to obtain documents related to the research topic and characteristics of open space and open space users in the city of Bandung, which will be discussed in this study. The process of obtaining primary data in this study was carried out with a primary survey method, including observing and distributing questionnaires to open space users. Observation through direct visual observation to find out and record the actual state of the area in the field. The instrument used is an observation sheet with a camera. Questionnaire data collection using questionnaire sheets containing a list of questions addressed to respondents in public spaces as primary data for the analysis phase. The form of the questionnaire is adjusted to identify the socio-economic characteristics of open space visitors, as well as taking aspirations, needs and preferences of the community related to quality improvement and inclusiveness in city-scale public open spaces.

Sampling

The population in this study were visitors to city parks in the city of Bandung. The type of sampling used in this study is probability sampling. In probability sampling, elements in the population have the opportunity to be selected as sample subjects. The probability sampling design is used to represent the characteristics of the sample subgroup (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). A sampling at each park is strived to capture the representation of the characteristics of male and female visitors. To compare each type of park, data from 100 people were taken to sample thematic parks and 100 people to sample the square. Questionnaires were distributed on weekdays and weekends in the morning and evening hours in the first week of May 2019.

Variables

The variables used in this study are physical access, social access, access to activities and socio-economic characteristics of a park visitor. The types of access used in this study as revealed by Ercan and Memlük (2015), some variables used by Mehta (2014), and adjustments to the local context. Physical access is s the ability of space to be accessible by everyone physically. Social access is defined by the presence of cues/signs, in the form of people, design and management elements, which indicate who is accepted and not accepted in space. Access to Activities is defined as the ability of public spaces to accommodate various activities that can be accessed by the public. We also find out the socio-economic characteristics of visitors because those characteristics affect inclusiveness. The list of variables is in Table

Analysis Method

At the stage of data processing and analysis, several methods and analytical tools are used to process data according to these steps.

• Analysis of the characteristics of park visitors

This analysis aims to determine the aggregate profile of park users based on gender, age, education level, and income level. This analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics based on data obtained from the results of the primary survey using a questionnaire to respondents of visitors to the public space.

• Analysis of park visit and activity characteristics

Usage pattern analysis is conducted to find out how the park is used by each respondent's characteristics. It also aims to identify the group of people who most often use the park based on the frequency of visits, the purpose of the visit, the modes used, activities carried out in the park.

• Analysis of park inclusiveness

The analysis of park inclusiveness level was done by scoring on the variables forming inclusiveness of public open space. Scoring and weighting are done so that the data is compared between thematic parks and public parks. The four components of inclusiveness in this study are (1) visitor characteristics, (2) physical access, (3) social access and (4) access to activities, given a scale score of 0-3 based on the constituent component variables.

Findings

Physical Access

Physical access in each park is determined based on scoring criteria, i.e. (1) the existence of gate tools for public spaces: padlocks, fences, etc.; (2) operating hours in public spaces (3) design elements prevent the use of space and (4) perception of park users about the ease of access to the park. Based on physical access assessment, non-thematic parks have a slightly higher score than thematic parks. In the variable presence of gate tools for public spaces: padlocks, fences, film parks get a lower value because there is only one access in the form of stairs without other alternatives. Non-thematic parks can be entered from all directions, but the thematic parks have more certain entrances. Park visitors interpreted physical access similarly between public parks and thematic parks.

Social Access

Social/symbolic access in each park is determined based on scoring criteria, i.e. (1) the existence of symbols to exclude specifics activities/people; (2) the existence of surveillance/CCTV cameras, security officers, guides, intimidation, and invasion of privacy; (3) visibility of public space; (4) visual and physical connections to streets or spaces; (5) perception of intimidating instruments; (6) perception of the presence of signs causes discomfort (7) emotional bonds between place and user and (8) safety perception.

In the variable of emotional ties, there is a low score both the thematic park and non-thematic park. Respondent’s feelings of safe tend to be perceived equally between thematic parks and public parks. Based on questionnaires, non-thematic parks are seen to have more signs which cause discomfort to park visitors.

Access to Activities

Access to Activities in each park is determined based on scoring criteria, i.e. (1) range of activity and behavior; (2) community presence in the third space; (3) space flexibility according to user need; (4) the perceived ability of the place to do and engage in activities and events in the public space; (5) visitor's perception of the suitability of the design; and (6) economic activities. Overall, non-thematic parks have higher access to activities than thematic parks. Access to activities was captured based on observations in figure

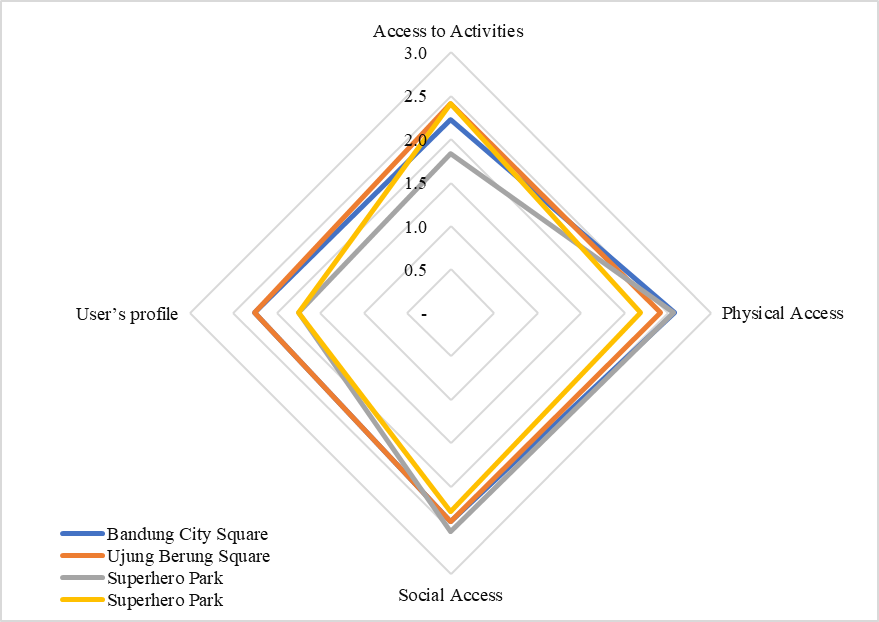

Assessment of Inclusivity level

The assessment of the inclusiveness level consists of aspects of activity access, physical access, social access, and characteristics of the user. Overall, public parks are considered more inclusive of all elements compared to thematic parks. But the difference in value in the thematic parks and public parks is relatively thin, with a close gap.

Based on scoring those variables, non-thematic parks activities have a higher score than thematic parks (Figure

The assessment of inclusiveness level consists of aspects of activity access, physical access, social access, and characteristics of a park visitor. Overall, public parks are considered more inclusive from all aspects compared to thematic parks. But the difference in value in the thematic parks and public parks is relatively thin, with a close gap.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Based on the review of the literature on public space inclusiveness, accessibility is a crucial measure or indicator of inclusiveness. Assessment of inclusiveness indicators can be explained through visitor characteristics, physical access, social access, and access to activities.

Findings related to the level of garden inclusivity are as follows:

Physical access: public parks have better physical access with the value of non-thematic parks (value 2.5 on a 3.0 scale) and thematic parks (value 2.4 on a 3.0 scale)

Social access: thematic parks and non-thematic parks have the same social access value (value 2.4 on a 3.0 scale)

Access to activities: public parks have better access to activities with a non-thematic park value of 2. on a 3.0 scale and thematic parks of value 2 on a 3.0 scale.

Non-thematic parks are considered more inclusive in all aspects than thematic parks. But the difference in value in the thematic parks and public parks is relatively thin, with a close gap.

Based on the analysis of the inclusiveness level of public open spaces in Bandung, non-thematic parks are considered more inclusive than thematic parks in terms of physical access, access to activities and visitor characteristics. By assigning a theme, relatively small parks can serve more citizens of the city and community. Also, the frequency of visitors to thematic parks is higher than non-thematic parks. The slight difference in the level of inclusivity indicates that there is potential for the development of thematic parks to be more inclusive. One other important note is that the provision of parks in Bandung has not yet paid attention to access to people with disabilities. Despite these shortcomings, with the right strategy, thematic parks have high potential to become inclusive public spaces.

Recommendation

The recommendations from this study are expected to be one of the findings for inclusive city development. With the increasingly diverse activities of city dwellers, public space must be able to accommodate various activities. For thematic parks, the following suggestions are proposed that can be made by the government or stakeholders regarding city/thematic public spaces:

Improved physical access, by providing thematic parks with access to public transportation, building easy access to people with disabilities, providing parking, and increasing entrances and operating hours.

Increased social access, by implementing an inclusive design, increasing security but not intimidating, increasing the presence of signs, the provision of events/activities in the park that involve the wider community.

Increased access to activities, by building facilities to broaden the range of activities, encourage and incentivize communities in using parks, provide space and keep control of economic activities. A comprehensive policy is needed to provide access to all public spaces for persons with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB) through the 2018 Research, Community Service and Innovation Program (

References

- Ari, M. M., Zulkaidi, D., & Pratiwi, W. D. (2016). Evaluasi Dampak Penyediaan Taman-Taman Tematik Kota Bandung berdasarkan Persepsi Masyarakat Sekitar [Impact Evaluation of Bandung Thematic Parks Provision based on Local Community Perception]. Prosiding Temu Ilmiah IPLBI 2016, 8.

- BAPPEDA Kota Bandung. (2014). Kajian Konsep Pengembangan dan Pengelolaan Taman Kota menjadi Taman Tematik di Kota Bandung. [Study of the Concept of Development and Management of City Parks into Thematic Parks in Bandung].

- Carr, S., Stephen, C., Francis, M., Rivlin, L. G., & Stone, A. M. (1992). Public Space. Cambridge University Press.

- Ercan, M. A., & Memlük, N. O. (2015). More inclusive than before? The tale of a historic urban park in Ankara, Turkey. Urban Design International, 20(3), 195–221. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2015.5

- Garau, P. (2017). The Biennial of Public Space in Rome. From the Charter of Public Space to the Post-Habitat III Agenda. The Journal of Public Space, 2(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.5204/jps.v2i1.59

- Garvin, A. (2016). What Makes a Great City. Island Press.

- Gehl, J. (2011). Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. Island Press.

- Ilmiajayanti, F., & Dewi, D. I. K. (2015). Persepsi Pengguna Taman Tematik Kota Bandung Terhadap Aksesibilitas Dan Pemanfaatannya [Visitors Perception of Bandung Thematic Park Accessibility and Utilization]. RUANG, 1(1), 21-30. https://doi.org /10.14710/RUANG.1.4.21-30

- Langegger, S. (2016). Rights to Public Space: Law, Culture, and Gentrification in the American West. Springer.

- Madanipour, A. (2010). Whose Public Space?: International Case Studies in Urban Design and Development. Taylor & Francis.

- Maftuhin, A. (2017). Mendefinisikan Kota Inklusif: Asal-Usul, Teori dan Indikator [Defining Inclusive Cities: Origins, Theories and Indicators]. TATALOKA, 19(2), 93. https://doi.org/10.14710/tataloka.19.2.93-103

- Mehta, V. (2014). Evaluating Public Space. Journal of Urban Design, 19(1), 53–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2013.854698

- Ramadhani, B. (2015). Identifikasi Potensi Pembentukan Ruang Terbuka Publik pada Taman Tematik di Kota Bandung [Identification of Potential for Establishing Public Open Space for Thematic Parks in Bandung City] (Undergraduate Thesis). Institut Teknologi Bandung.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Subramanian, D., & Jana, A. (2018). Assessing urban recreational open spaces for the elderly: A case of three Indian cities. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 35, 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.08.015

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. (2015). Global Public Space Toolkit from Global Principles to Local Policies and Practice. United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- Woolley, H. (2004). Urban Open Spaces. Taylor & Francis.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

12 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-088-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

89

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-796

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues, urban planning, municipal planning, disasters, social impact of disasters

Cite this article as:

Sugiana, E., & Kustiwan, I. (2020). Inclusivity of Thematic Park as a Public Space in Bandung City. In N. Samat, J. Sulong, M. Pourya Asl, P. Keikhosrokiani, Y. Azam, & S. T. K. Leng (Eds.), Innovation and Transformation in Humanities for a Sustainable Tomorrow, vol 89. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 116-126). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.02.11