Abstract

Each language reflects reality in accordance with its structural and conceptual peculiarities. Comparison of reality conceptualization across cultures helps to reveal allomorphic and isomorphic processes in different languages, which facilitates immersion in a new linguistic and conceptual reality and understanding of the degree of coincidence / discrepancy in mental complexes formed by different languages. The aim of this work is to establish the peculiarities of somatic phraseology conceptualization in Russian and English based on two samples of idioms. The research is based on a current approach to the study of linguistic units and phenomena from the point of view of cognitive linguistics – a scientific paradigm that takes into account not only the structure of the language, but also its connection with human cognition, which helps to reveal the differences and similarities in the mentality of individuals and communities belonging to different cultures. This study is based on a systematic approach with the employment of the methods of componential, conceptual, and comparative analysis alongside cognitive modelling of idiomatic somatic conceptual spheres in the Russian and English languages. The results of the study show that the conceptual spheres in two languages are extremely heterogeneous both in the number of idiomatic expressions and in the meanings of Russian and English idioms that coincide in their somatic components, which is connected with the historical and cultural development of the linguocultures under study. However, since somatisms are biological universals, the percentage of conceptual matches is also quite representative in the two linguocultures under study;

Keywords: Conceptconceptual sphereidiomsomatic component

Introduction

Conceptualization of reality has been studied by a large number Russian and international scientists (Yu.D. Apresyan, A. Vezhbitskaya, E.S. Kubryakova, V.I. Karasik, D.S. Likhachev, V.V. Maslova, Z.D. Popova, S.G. Ter-Minasova, I.A. Sternin, Yu.S. Stepanov, G. Lakoff, G. Fauconnier, M. Turner, etc.) who interpret it as a way of perceiving and structuring the world, as a cognitive activity of a person, the result of which is the formation of concepts, conceptual structures, conceptual spheres and the entire conceptual system ( Apresyan, 1995). Zykova ( 2017) calls the process of concept formation cultural genesis, i.e. the process of creating the conceptual sphere of culture, in which concepts generated by experience and by understanding of the world take on iconic forms. The result of conceptualization is a conceptual picture of the world, which can be partially understood through the language that forms the linguistic picture of the world. The linguistic picture of the world reflects the surrounding world refracted through the prism of national and cultural specificity and individual characteristics of a person. The conceptual picture of the world is closely connected with language and is determined by it, since cognition of the world is carried out not only on the basis of empirical perception, but also with the help of abstraction and generalization ( Alefirenko, 2016; Džanić & Berberović, 2019; Maslova, 2018). The conceptual picture of the world is based on a certain set of universals also known as basic concepts. According to Hickmann ( 2009), universals are divided into functional and formal ones. Formal universals affect the grammatical sphere of the language, while functional universals belong to the areas of cognition and communication. Functional universals can be conditionally divided into the following subtypes:

cognitive universals: general ideas about the world that children master in the first place (for example, spatial and temporal relationships);

semantic universals: representations that relate to the organization of linguistic categories;

pragmatic universals: basic concepts related to the situation of communication (for example, interlocutors’ social roles).

Problem Statement

Somatic vocabulary (from the Greek

Research Questions

The understanding of the verbal representation of the physical body of a person through the prism of culture from the point of view of the cognitive-cultural approach seems relevant, as it allows understanding how cognitive structures are reflected in the structure and semantics of phraseological units (idioms) and how the understanding of the world representing a particular culture is manifested. Idiomatic expressions, or idioms as culturally marked combinations of words characteristic of a certain language is a valuable source of information about the conceptualization of the world through the prism of a particular culture. Cross-cultural comparison of idioms may help to identify how universal somatic elements form cultural associations in different languages, i.e. how similar or different these associations are in the languages and cultures under study.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to identify the specificity of reality conceptualization through idioms with somatic components in Russian and English. The following dictionaries served as sources of English idiomatic units: Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries and the Great English-Russian Phraseological Dictionary by A. V. Koonin. Sources of Russian phraseological units were phraseological dictionaries of the Russian language by E. A. Bystrova, A. I. Molotkov, V. N. Telia, I. V. Fedosov. For analysis and comparison, 124 English and 129 Russian idioms with a somatic component were selected.

Research Methods

The selection of phraseological units was carried out according to the somatic keyword, which is included in an idiomatic expression, or an expression that implicitly refers to somatisms. By the method of continuous sampling, Russian and English idioms with the following somatisms were selected:

All the units of the sample were divided into groups according to somatic components, and Russian and English units containing similar somatisms were compared according to conceptual phraseological meanings (hereinafter referred to as concepts) identified by means of the componential analysis of dictionary definitions of idiomatic expressions. The conceptual phraseological meaning is understood as the content plane of the phraseological sign, in which two interrelated levels are distinguished: semantic and conceptual. The semantic level can be described as a collection of semes. The source of the formation of the semantic level is the conceptual level, understood as a structured set of various conceptual components, on the basis of which a holistic phraseological image is synthesized (Zykova, 2016a, 2016b).

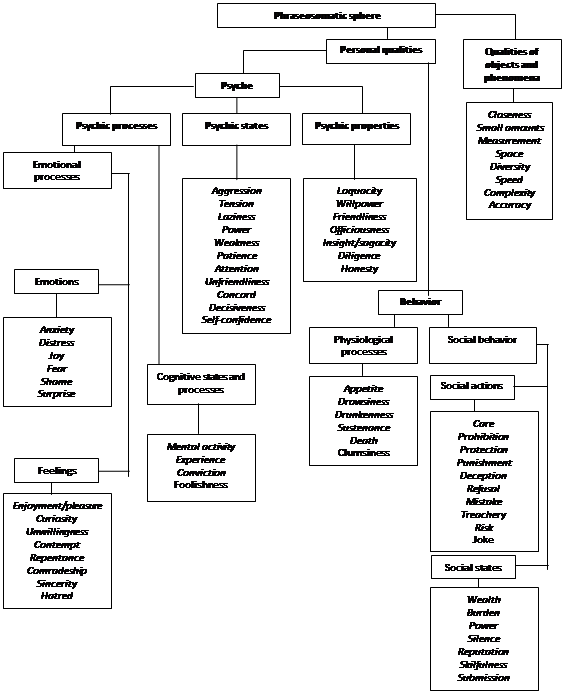

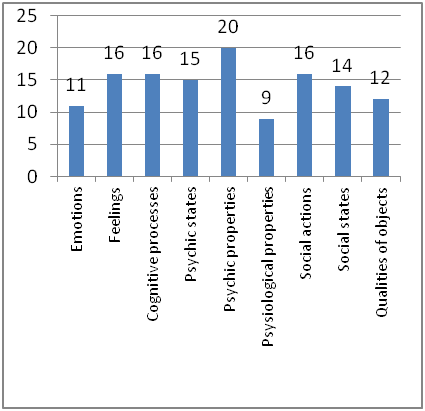

All the concepts associated with a somatism included in an idiom were combined into conceptual spheres forming a hierarchical structure (see Figure

All concepts expressed by the somatic idioms (see Fig.

Findings

A comparison of Russian and English idiomatic expressions with equivalent or similar parts of the body revealed a low percentage of similar concepts (27% in Russian and 28% in English of the total number of the samples) and a high percentage (73% in Russian and 72% in English) of conceptual inconsistencies. 72-73% of idiomatic expressions that coincided in somatic components included into idiomatic expressions have a mismatch at the lexical-structural and semantic levels. Nevertheless, basic conceptual coincidences (27-28%) can be traced in almost all somatic components presented in the samples. For example, phraseological units containing the following somatic components coincide in their general conceptual features:

The remaining sample cases (70%), which are identical in somatic elements (or partially coincident, in the case of the somatisms

The hierarchical conceptual structure shown in Fig.

As an example, let us introduce the subsphere psychic

The conceptual sphere

The state of aggression / lack of aggression is presented in both languages by the somatic components

The state of laziness in both languages is associated with the inability of the individual to move one’s finger (

The state of attention is also expressed in a similar way with the help of the somatic element

Another concept expressed in a similar manner both in English and in Russian is the concept of patience, where in both cases the cheek is related to the saying of the biblical origin (

The states of strength and weakness in Russian and English are expressed through different somatic elements (

Other concepts, such as

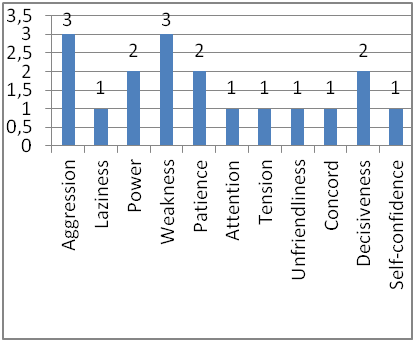

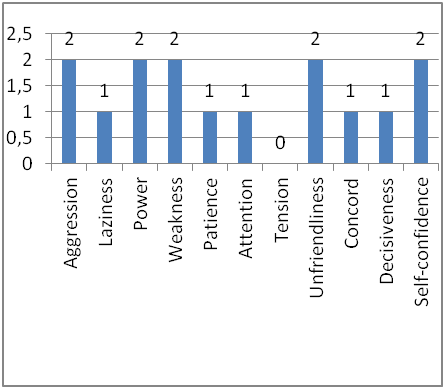

The analysis of the frequency of occurrence of idioms belonging to the sphere of psychic states revealed the following features (see Figures

On the basis of these diagrams, we can conclude that the English sphere representing psychic states contains more idiomatic expressions with somatic elements than the Russian sphere. In the English sphere, 11 psychic states are represented by somatic idioms, whereas in the Russian sphere 10 of the 11 states are represented. The concepts of

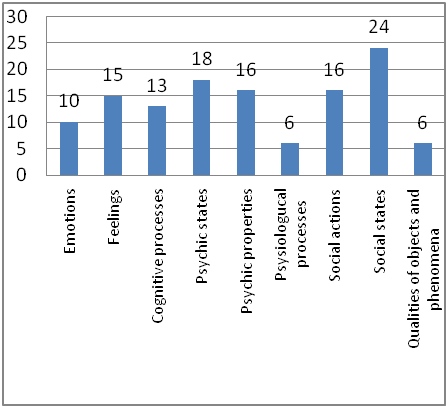

Similarly, a comparative analysis of all the subspheres of the phraseosomatic conceptual sphere was performed (see Fig.

Comparative analysis of the diagrams showed that despite the similar set of subspheres related to the conceptual spheres of personal qualities and qualities of objects and phenomena in the Russian and English samples their ratio differs. The English sample is dominated by concepts such as

From the point of view of the frequency of usage of somatic elements in the Russian and English samples, it can be concluded that idioms with such somatic elements as

Conclusion

Thus, on the one hand, somatisms belong to universals, which explains the percentage of coincidences in the conceptualization of reality. Nevertheless, in the universal somatic picture of the world there are features associated with different approaches to dividing the human body into segments. In English linguistic culture, a more fractional differentiation of the upper and lower limbs is observed (different lexemes for fingers and toes (

On the other hand, similar conceptual spheres in Russian and English are extremely heterogeneous in terms of phraseological units in each conceptual sphere and in terms of the wording of phraseological units that coincide in conceptual and somatic components in Russian and English, which indicates the historical and cultural peculiarities of Russian and English cultures.

The isomorphism of English and Russian pictures of the world is also manifested in the dominance of the global conceptual sphere of “personal qualities”, which indicates an anthropocentric approach to understanding the surrounding reality in English and Russian linguistic cultures. Allomorphism manifests itself in the differences in such areas as

References

- Alefirenko, N. F. (2016). Lingvokulturologija. Cennostno-smyslovoe prostranstvo jazyka [Linguoculture. Axiological and semantic aspects of the language]. Flinta.

- Apresyan, Ju. D. (1995). Obraz cheloveka po dannym jazyka: popytki sistemnogo opisanija. Izbrannye trudy, tom II: Integralnoe opisanie jazyka i sistemnaja leksikografija [The image of a person according to language data. Selected Works, Volume II: Integral Language Description and Systemic Lexicography]. JaRK.

- Cardwell, M. (2014). Dictionary of Psychology. Routledge.

- Džanić, N. D., & Berberović, S. (2019). Conceptual Integration Theory in Idiom Modifications. Universitat de València.

- Dzakhova, V. T., & Dzodikova, Z. B. (2018). Frazeologizmy kak otrazhenie mirovozzreniya naroda (na materiale analiza frazeologizmov s komponentami Ud/Dusha/Seele v osetinskom, russkom i nemeckom yazykah) [Phraseologisms as reflection of people’s mentality]. Litera, 2, 20 - 25.

- Hickmann, M. (2009). Children’s Discourse. Person, Space and Time across Languages. Cambridge University Press.

- Gilmutdinova, A. R., & Samarkina, N. O. (2016). Phraseological world picture (based on phraseological units with the component, related to the phraseosemantic field «music» in the English and Turkish languages). Philologicheskie nauki, 4(46), 43-45.

- Klevtsova, O. B. (2007). Koncept “chelovek telesnyj”: kognitivnoe modelirovanie i perenosy (na materiale sopostavitel'nogo analiza drevnerusskogo i drevneanglijskogo jazykov) [The concept of a human body: cognitive modelling and transfers (on the basis of a comparative analysis of the Old Russian and Old English languages):]: Cand. Sci. (Philol.) diss.: Tyumen State University.

- Kovshova, M. L. (2016). Kulturno-nacionalnaya specifika frazeologizmov i voprosy eksplikacii ih kulturnyh smyslov [Cultural and national specificity of phraseological units and explication of their cultural meanings]. Voprosy psikholingvistiki, 90-102.

- Leontyev, A. N. (1971). Potrebnosti, motivy i jemocii [Needs, motives and emotions.]. Izdatelstvo Moskovskogo Universiteta.

- Maslova, V. A. (2018). Vvedenie v kognitivnuju lingvistiku: uchebnoe posobie [Introduction to cognitive linguistics]. Flinta.

- Samchik, N. N. (2019). “Chelovek telesnyj” v sravneniyah russkogo, anglijskogo i nemeckogo pesennogo folklora [“Homo corporis” in comparisons of the Russian, English and German folklore]. Baltiiski gumanitarny zhurnal, 8(2), 321-323.

- Zykova, I. V. (2016a). Linguo-cultural studies of phraseologisms in Russia: past and present. Yearbook of Phraseology, 7, 127–148.

- Zykova, I. V. (2016b). Perception of verbal communication reflected in Russian and English phraseology: Towards a new theory of phraseologism-formation. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 236, 139–145.

- Zykova, I. V. (2017). Metayazyk lingvokul'turologii: Konstanty i varianty [Linguoculture metalanguage: variables and invariables]. Gnozis.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

03 August 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-085-3

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

86

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1623

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, translation, interpretation

Cite this article as:

Ponomareva, E. Y., & Pavlyuk, A. S. (2020). Conceptualization Of Reality By Means Of Russian And English Somatic Idioms. In N. L. Amiryanovna (Ed.), Word, Utterance, Text: Cognitive, Pragmatic and Cultural Aspects, vol 86. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1133-1142). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.08.131