Abstract

Parents influence their children from the beginning because the foundations of spiritual, moral and religious education are early foundations within the family, however, it is quite difficult to identify the existence of links between the manifestation of the specific behaviors of the parents and the subsequent behaviors of the children. Defining the attitude of parents towards religious education as a certain conception of parents towards which they express their position and manner, by which they firmly state their point of view towards religious education we consider this variable to be relevant in the context of religious education, both for parents self-portraying their parental style as well as those for whom we identify certain particularities of parental practices. The existence of responsible factors for the institutionalized religious education and the constant reporting of the influences they exert on the students, determined to analyze, to what extent parents can influence the educational process regarding religious education carried out in school, taking into account the self-reported parental styles and their identified personality factors.

Keywords: Religionattitudeeducationparents

Introduction

Parental attitude refers to the parents’ way of being or behaving, often representing a certain conception to which they express their position and firmly asserts their point of view. Horga, Cuciureanu, and Velea (2008) addresses the aspect of parents' attitudes towards religious education and shows how parents, in consonance with their children, have similar attitudes to religious practices and the importance of religious education. The foundations of spiritual, moral and religious education are grounded early in the family, and in terms of the success of religious education, parents have positive appreciations. The study of the Institute of Educational Sciences in Bucharest, conducted in 2008, shows that 53.5% of the investigated parents often guide their own behavior following religious belief, and 64.2% of parents identify their religious behavior in their children.

Through religious education the school makes an appropriation where the family feels represented and supported by this institution. At the same time, when talking about religion as a subject of education, parents show through their parental attitude, the self-reported and self-identified one, the expectations regarding the way of religious education is carried out in the school.

Most surveyed parents (Horga et al., 2008) believe it is good for religion to be taught throughout the whole school period. Parents who support teaching religion in compulsory or even secondary education are especially those from the countryside, while teaching religion in primary education is supported more by the parents from the urban environment (Horga et al., 2008).

McLaughlin and Jordan (2005) noted that parents' example and attitudes were the most important elements of religious education for their children. Also, parental influence has proven to be the most important influence recognized in the religious development of young people before the influence of church teachings, while non-institutionalized religious teachings have been shown to have a less important influence (Maroney, 2007). Parents and the parenting style are the strongest influences in a child's religious development (Armet, 2009; Baumrind, 1978; Boyatzis, 2003). The values are more successfully transmitted when children feel they have been given the opportunity to choose their own religious beliefs (Vermeer, Janssen, & Scheepers, 2012) and that their religious choices have been generated by themselves (Armet, 2009; Baumrind, 1978; Grusec, 1997). The parental attitude that encourages autonomy, while providing moderate supervision, is most likely to support the development of a healthy religious identity (Dudley, 1978; Ellison & Sherkat, 1993; Myers, 1996).

Parental style as a concept refers to the normal variations of attempts to control and socialize the children by parents (Baumrind, 1978). Two aspects are important in this definition: firstly, parenting styles describe normal variations in parenting practices, so they should not be understood as deviant styles of parental practices such as abuse or neglect and secondly, Baumrind (1978) started from the idea that normal parenting practices revolve around the notion of control. Although parents may differ in how they try to control or socialize their children, and as far as they do, it is assumed that the primary role of parents is to influence, educate and control children.

The authoritarian parent was found to be directly and indirectly associated with pro-social behavior in adolescents (Gunnoe, Hetherington, & Reiss, 1999). Wheeler (1991) found that children of authoritarian parents are the most likely to have a high level of self-development and self-control of the exploration. Instead, children of democratic parents have been identified as more active in facilitating and exchanging content by contributing to their development (Boyatzis, 2003). Children of authoritarian parents, on the other hand, may be more dissatisfied, withdrawn, and disbelievers (Boyatzis, 2003). The children of permissive parents indicate a lower dependence, but they are exploratory and with a low level of control (Wheeler, 1991). Research on religious education has questioned the importance of authoritarianism represented by the person who has a rigorous view of religion, that is very well defined and strict, but rather about authority and control.

If parents are authoritative, they are likely to tend towards a controlling parental style and insist on their children’s obedience, even if they are religious parents (Danso, Hunsberger, & Pratt, 1997).

Baumrind (1978) suggested that most parents have one of the following three types of parenting styles: the authoritarian, the democratic and the permissive parent. Further research (Maccoby, 2000) suggested the addition of another style besides the three initially proposed, the non-implicit, but this type will not be included in the present research.

We propose for our research this relevant theoretical models.

Parents involvement (Singh et al., 1995) identified four components of parental involvement: parents' aspirations for children (parents' hopes and expectations for the child’s continuous education), parent-child communication about school, family structure (parental discipline) and parental involvement in school-related activities.

Parental control exercised through an encouraging environment is recognized as beneficial to the social development of adolescents (Sartor & Youniss, 2002), Taylor and Oskay (1995) confirming that in cultures in which parental control is practiced, adolescents perceive their parents as warmer and more receptive. Generally, in organized families where parents are involved in educating their children are seen as more reasonable, more dedicated and more accessible (Sartor & Youniss, 2002).

Problem Statement

The presence of specialized literature on the relationship between attitude and religious education, forces us to refer only to the actors identified by the exploratory analysis, thus, we can suppose that they largely reflect our construction. As an educator, I noticed a change in parental attitude regarding religious education and I was interested in the reasoning behind these changes. Closely analysing the context but also the factors which led to this change would be a first step towards a better understanding of this issue, and, moreover, offering acceptance and support to the parents, resulting in an active participation in religious education, formally and informally.

Research Questions

We expect to identify the factors responsible for the religious attitude based on the items constructed following the frequency analysis of the answers given by the parents regarding the concept of religious attitude and the relationship between the main factors of the proposed questionnaire for validation. In exploring the attitudinal forms of the parents we will use advanced factorial analysis to show us the main factors identified as those that "cover" the studied construction, that of the parental attitude towards religious education. We expect differences regarding the attitude of parents towards religious education according to parental style, gender of subjects and especially regarding confessional orientation, known that in our country the preponderant religion is the orthodox one and therefore we anticipate results that will guide us towards this opinion, according to which the Orthodox parents would foretell a certain parental style adopted regarding religious education.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the research is to identify parents' attitudes about religious education with five dimensions or determinants, to analyze the factorial structure of the questionnaire and its internal consistency, correlations with other relevant variables, and differences depending on demographic variables. Based on these dimensions, five factors were synthesized in the main attitudinal forms: regarding the organization of religious education (teaching method, the class progress), how or when to teach religion in school, the role of religious education, the participation of the students in the religion class as well as the involvement of the parents in the teaching of the religion class, so the parents had to evaluate on a Likert scale according to their agreement or disagreement the opinion regarding certain attitudes regarding the religious education.

For this stage of the research, the survey method has been used by building a questionnaire on parents' opinion on religious education achieved in school. Parents were asked to answer some open questions about the advantages and disadvantages of religious education. Based on the answers given, we have built a number of items to see what do the parents think of the religious education performed in school. These results have been linked, also at this stage, to those received from the parents after the PQI questionnaire has been applied, which identified the parental style.

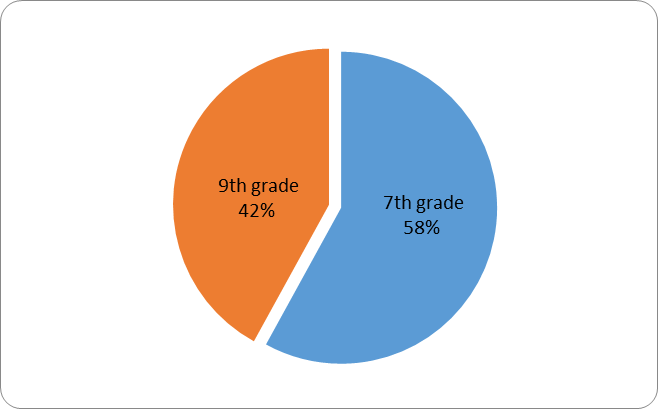

For starters, I propose to apply to the parents the PQI and the parent attitude questionnaire for religious education undertaken in school. The latest research (Horga et al., 2008) shows that religion needs to be taught throughout the children school years, and that there are reserves related to the way religious education is taught and organized (building a moral-religious behaviour). The parents have responded to the items regarding the teaching way, but also to the way religious education is carried out in school. The participants are parents whose children are enrolled in 7th and 9th grades.

Research Methods

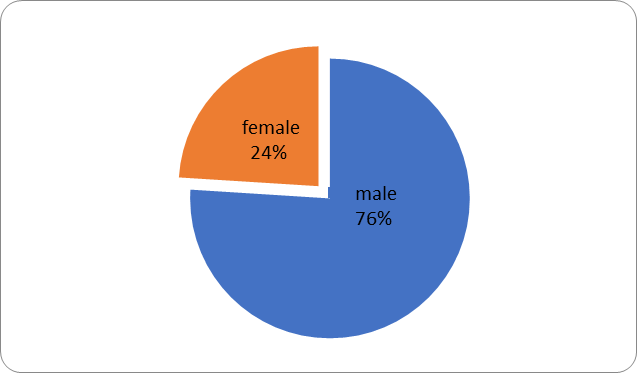

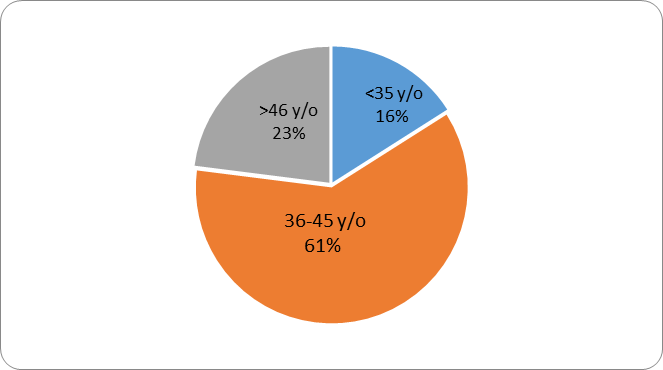

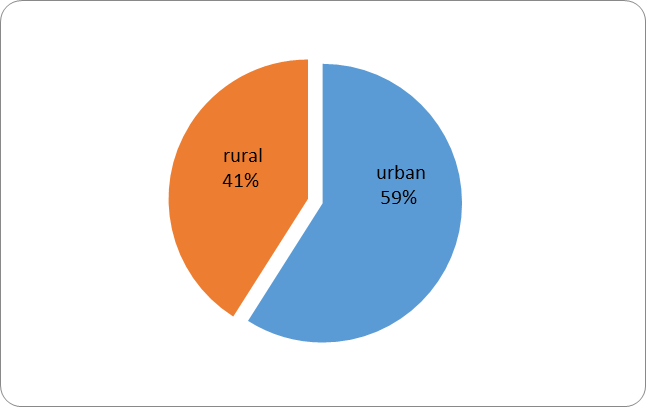

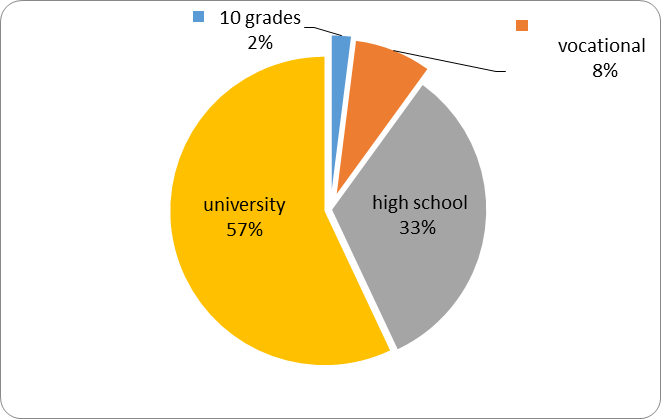

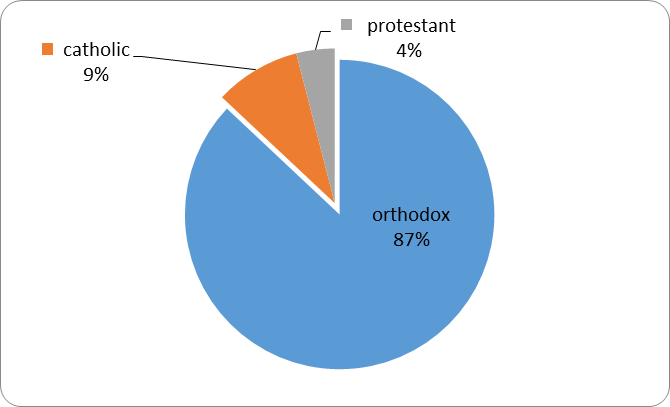

This study was attended by 411 parents (76% men and 24% women). 61% of parents are between the ages of 36 and 45, 16% are under 35, and 23% are over 46 years of age). 59% of them live in urban areas (41% in rural areas) and 57% of all participants have graduated from university (2% graduated 10 grades, 8% vocational school and 33% high school). 58% of parents have children in the 7th grade (42% in the 9th grade). 87% of the parents are of Orthodox religion (9% Catholic, 4% Protestant). Participants were asked to respond to The Parental Attitudes Questionnaire (built) with 48 items per 5 factors or dimensions as well as the PQI Questionnaire of the parental authority (Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 1995). The questionnaire has 30 items, rated on a five-step Likert scale (1 means never, and 5 means always). It is structured in three sub-scales (permissive, authoritarian and democratic style) Item 1-13 style democratic, 14-26 authoritarian style, 27-30 permissive style. Self-reporting 1,2,3. Applied to parents. Parents will report regarding their parental style towards their children.

The questionnaires were completed in pencil-paper format and were distributed during the sessions with the parents of “Elena Cuza” School from Vaslui, “Strunga General School”, Iaşi County, “Leţcani General School”, “Octav Băncilă National Art College” Iaşi , Theoretical Lyceum "Emil Racoviţă", Vaslui and, lastly, Theoretical Lyceum “Miron Costin”. Participation in the study was voluntary. The following demographic data were considered: area of origin (Figure

Findings

The data was analyzed with SPSS for Windows 17.0. To test the distribution's normality, we applied the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and to test the internal consistency we applied the Alpha Cronbach test.

For the K-S test, we have achieved a significant statistical result (p = .00, which shows that there are significant differences between the normal distribution and the one obtained), for the following analysis, we have used non-parametric tests.

Whereas the Alpha Cronbach coefficient for some scales has not been above the accepted minimum value (α = .75), for further analysis we have removed a series of items (Table

In order to explore the factorial analysis, we applied the main component analysis. For a first analysis, we selected the option to check the factorial structure for factors that have an Eigenvalue above the value of 1. In this situation, the results showed a factorial structure in 7 factors, the last 4 containing a single item. Since one item (item 48) was proposed to be eliminated when analyzing the internal consistency, we repeated the factorial analysis, selecting 4 factors and eliminating item 48.

This factorial structure explained 54.90% of the total variation for rotation by the Varimax method. The percentages of item variants covered by each factor were: 31.29%, 11.79%, 6.72%, and 5.08%, respectively. Table

To test interscale correlations and the correlation with the Parental Style variable, we applied the Spearman test to assess the level of correlation between the scale of the attitude to religious education and parenting attitudes. In general, the results obtained support a strong average correlation between the five original scales of the APER questionnaire (r between .20*** and .71***). Except for the pupil participation scale that correlates negatively with the other scales, the results show a direct relationship (positive correlations) between the scales. As far as the relationship between attitude towards religious education and parenting is concerned, the results support a significant relationship only with democratic style. Thus, the student participation scale correlates negatively (r= .41***) and the other four scales correlate positively (with r between .19*** and .46***). Therefore, we can conclude that parents who adopt a democratic style are also those who are more prone to display a positive attitude towards religious education (Table

To test demographic variations, we applied the Mann-Whitney test, Krushkal-Wallis, respectively, to identify differences in attitudes towards religious education. For this study, there is a tendency for the attitudes towards religious education to be influenced by gender, for the method of organizing religious education scale (Z= -1.85; p = .06), meaning that fathers have a more positive attitude (= 3.59) compared to mothers (= 3.53). Regarding the role of religious education and the involvement of parents in teaching religion, fathers have a more positive attitude, while for the mothers' recorded a higher score in the participation in religion class (Table

Parents up to the age of 45 or those from rural areas have a more positive attitude towards religious education. The parents’ level of education is not a significant criteria for differentiation in all scales of attitude towards religious education; in this respect, regarding the role of religious education and student participation in religion, parents with 10 classes (χ2 = 9.15; p = .01) or with high school education are the ones who have the most favorable attitude for certain dimensions of the questionnaire (χ22 = 7.39; p = .02). Parents of Orthodox religion have a more positive attitude than parents of other religions regarding the role of religious education (χ2 = 11.82; p = .003) and parental involvement in teaching religion (χ2 = 12.80; p = .002).

Conclusion

In the present study, we aimed to analyze the internal consistency of the questionnaire on

Generally, the results recorded a similar trend to those in the literature, however, there were a few peculiarities for the analyzed group. As far as the relationship between attitude towards religious education and parenting is concerned, the results support a significant relationship only with democratic style. Thus, the student participation scale correlates negatively (r = .41 ***) and the other four scales correlate positively (with r between .19 *** and .46 ***). Therefore, we can conclude that parents who display a democratic style are also those who are more prone to display a positive attitude towards religious education.

For this study, there is a tendency for attitudes towards religious education to be influenced by gender, for the scale of organizing religious education, in the sense that fathers have a more positive attitude (

Parents up to the age of 45 or those from rural areas have a more positive attitude towards religious education. The parents’ level of education is not a significant criteria for differentiation in all scales of attitude towards religious education; in this respect, regarding the role of religious education and student participation in religion, parents with 10 classes or with high school education are the ones who have the most favorable attitude for certain dimensions of the questionnaire.

Regarding the role of religious education and the involvement of parents in the teaching of religion, fathers have a more positive attitude, while in regards to the participation in religion class, mothers have recorded a higher score. Parents of Orthodox religion have a more positive attitude than parents of other religions regarding the role of religious education and parental involvement in teaching religion.

On the basis of the results, in order to increase internal consistency, we propose that for the scale of organization of religious education (APER), the elimination of item 5; for scale

References

- Armet, S. (2009). Religious socialization and identity formation of adolescents in high tension religions. Review of Religious Research, 50(3), 277-297.

- Baumrind, D. (1978). Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence. Youth and Society, 9, 239-276.

- Boyatzis, C. J. (2003). Religious and spiritual development: An introduction. Review of Religious Research, 44(3), 213-219.

- Danso, H., Hunsberger, B., & Pratt, M. (1997). The role of parental religious fundamentalisman drightwing authoritarianism in child-rearing goals and practices. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 36(4), 496.

- Dudley, R. L. (1978). Alienation from religion in adolescents from fundamentalist religious homes. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 17(4), 389.

- Ellison, C. G., & Sherkat, D. E. (1993). Obedience and autonomy: Religion and parental values reconsidered. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 32(4), 313-329.

- Grusec, J. E. (1997). A history of research on parenting strategies and children's internalization of values. In J. E. Grusec, & L. Kuczynski (Eds.), Parenting and children's internalization of values. A handbook of contemporary theory (pp. 3-22). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Gunnoe, M. L., Hetherington, E. M., & Reiss, D. (1999). Parental religiosity, parenting style, and adolescent social responsibility. Journal of Early Adolescence, 19(2), 199.

- Horga I., Cuciureanu, M., & Velea, S. (2008). Moral and religious education in the Romanian education system. Bucharest: Institute of Education Sciences - Laboratory of Education Theory.

- Maccoby, E. E. (2000). Parenting and its effects on children: on reading and misreading behaviour genetics. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 1-27.

- Maroney M. (2007). An Exploration of Contemporary youth spirituality among senior school students. Journal of Religious education, 55(4), 22-30.

- McLaughlin, M. J., & Jordan, A. (2005). Push and pull: Forces that are shaping inclusion in the United States and Canada. In D. Mitchell (Ed.), Contextualizing inclusive education: Evaluating old and new international perspectives (pp. 89–113). London: Routledge.

- Myers, S. (1996). An interactive model of religious inheritance: The importance of family context. American Sociological Review, 61(5), 858-866.

- Robinson, C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77, 819-830.

- Sartor, C. E., & Youniss, J. (2002). The relationship between positive parental involvement and identity achievement during adolescence. Adolescence, 37(146), 221-234

- Singh, K., Bickley, P. G., Keith, T. Z., Keith, P. B., Trivette, P., & Anderson, E. (1995). The effects of four components of parental involvement on eighth grade student achievement: structural analysis of NELS-88 data. School Psychology Review, 24(2), 299- 317.

- Taylor, R. D., & Oskay, G. (1995). Identity formation in Turkish and American late adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26, 8-22.

- Vermeer, P., Janssen, J., & Scheepers, P. (2012). Authoritative parenting and the transmission of religion in the Netherlands: A panel study. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 22, 42.

- Wheeler, M. (1991). Relationship between parenting styles and the spiritual well-being and religiosity of college students. Christian Education Journal, 11(2), 51-61.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 June 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-084-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

85

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-814

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Mocanu, A. (2020). Inventory Of Parents' Attitudes Toward Institutionalized Religious Education, Explorer Analysis. In V. Chis (Ed.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2019, vol 85. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 743-756). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.06.78