Abstract

Objective: Brain tumour diagnosis affects the lives of many patients, and the burden can be overwhelming for patients with psychiatric disorders. The study intends to investigate on inter-relationships between quality of life, coping styles, social support, clinical factors and demographic impact on depression and anxiety among Malaysian neurological disorder (brain tumour / brain disorder) patients.Methods: Participants were assessed with numbers of measures: socio-demographic, Medical Information, EORTC-Quality of Life,Brief COPE, Single Item Social Support, MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview and Patient Health Questionnaires.Results: In the structural equation modeling of neurological disorder patients(brain tumour / brain disorder), all 8 paths were significant with p-values less than 0.05 (two-tailed) with R2 values ranging from 0.48 to 0.55 which indicates that the variance explained ranged from 48% for emotional functioning to 55% for severity of depression. The insomnia and panic disoder lifetime have positive relationship with severity of MDD. The self distraction coping styles has negative relationship with severity of MDD (p=0.005). The fatigue (p<0.001), venting (p=0.015) and panic disorder lifetime (p = 0.010) were found to have a negative relationship with emotional functioning score while global health status has positive relationship with emotional functionig (p < 0.001). Emotional functioning was found to have significant negative relationship with severity of MDD (p=0.03). Conclusion: Therefore based on SEM analysis, the main contributing factors of severity of MDD among the brain tumour / brain disorder patients were fatigue, insomnia, venting coping styles and panic disoder lifetime.

Keywords: Brain tumour/ disorderDepressionAnxietyQuality of life & Coping

Introduction

Brain tumour especially primary tumour cases account for only 2% compared to other types of cancers and worldwide, it affect 7 per 100,000 population annually (Arber, Faithfull, Plaskota, Lucas, & de Vries, 2010; Parkin, Whelan, &Ferlan, 2005). Cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide; in 2012, it was the cause of approximately 8.2 million deaths (Ferlay, et al., 2015). The gliomas are the most common primary brain tumours such as astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and ependymomas which originated from the glial origin. The tumours which are not from the glial origin include the meningiomas, schwannomas, craniopharyngiomas, germ cell tumors, pituitary adenomas, and pineal region tumors. It is interesting to note that the 40%-55% of all brain tumors are gliomas and 15%-25% are metastasizing to the brain (Price, Goetz, & Lovell, 2007). The malignant gliomas are reported to account for 34.6%, followed by medulloblastoma 11.3% and meningothelial tumours 3.1% of all nervous system tumours in year 2003 till 2005 in Peninsular Malaysia (Lim, Rampal, & Halimah, 2008)

Anxiety

Anxiety covers a broad spectrum of disorders, which includes panic disorder (Association., 2000). Form of response to any treat known as anxiety (Lienard, et al., 2006). Anxiety covers a broad spectrum of disorders, which includes panic disorder. Patients might face anxiety while waiting for the results of their diagnosis from their physician and pre and post procedures of their surgery (Ashbury, Findlay, & Reynolds, 1998). Anxiety interfere with emotional distress and functioning of the patients (Lienard, et al., 2008). The most common symptoms faced by the brain tumour patients before the surgery were anxiety (82%), agitation (75%), irritability (74%), depression (74%), and insomnia (70%). The anxiety and insomnia found to be increased at 1 month, however the symptoms were reduced at 6th month of follow up with 33% each for depression, anxiety and insomnia and 25% each for agitation, irritability, and disinhibition. The delusion was (21%) before surgery and reduced to 18% at 1 month of post surgery. The hallucination, elation, apathy, and motor symptoms found to be reduced at 1st month and decreased further at 6th of follow-up. Even though the neuropsychological symptoms at 6 months improved, the agitation, depression, anxiety, disinhibition, irritability, insomnia symptoms were persisted at the 6th month of post surgery (Dhandapani, Gupta, Mohanty, Gupta, & Dhandapani, 2017);

Problem Statement

The development of tumour progression treatment has been modest and it has been reported to be associated with various adverse effects such as delayed wound healing, hypertension, thrombotic events and congestive heart failure (Ahluwalia and Gladson, 2010). Therefore, there is a need for the improvement and development of current therapeutic treatment in the management of neurological disorder patients, as none of the available treatments have been shown to be sufficient to either prevent or treat the disease effectively in the patients.

Oncologists, primary care practitioners, and mental health professionals should be aware of the psychological consequences of cancer diagnosis, and further steps must be implemented to minimize undiagnosed psychiatric disorders that are left untreated. Instead of pharmacotherapy or medication, psychotherapy should also play a role in implementing effective treatment to increase the overall survival of cancer patients (Jackson and Jackson, 2007).

Research Questions

It is important to know about the overall relationship of MDD, anxiety disorders, other psychiatric disorders, quality of life, coping styles and their associated factors among neurological disorder patients.There is a need for data in oncology settings in this country in order to implement cost-effective treatments for those who need psychiatric services and to devise flexible interventions using local resources. Research is needed to extensively investigate depression and anxiety together with clinical factors, quality of life and coping styles in order to improve overall curability of the patients

Purpose of the Study

Our objective is to investigate the inter-relationships between quality of life, coping styles, social support, clinical factors and demographic impact on depression and anxiety using a complex structural equation modeling. Moreover, to date, no studies have been conducted to assess the inter-relationship between clinical factors, quality of life, coping styles, social support and demographic impact on depression and anxiety among the intracranial tumour and other brain disorders. Therefore the study aimed to determine the quality of life and coping styles impact on the severity of depression and anxiety among the intracranial tumour and other brain disorders patients. Therefore it is important to know how the inter-relationship exists between quality of life, coping styles, social support, clinical factors and demographic impact on depression and anxiety in the patients.

5.Research Methods

5.1.Study location

The study was conducted at Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL), a referral centre for neurological cases. All the patients were recruited between (April 2016 to December 2016). A cross sectional study design was applied in the study. Hundred patients with intracranial tumour or brain disorders were enrolled in the study. Interviewer (first author) for this research was trained by senior psychiatrists who are certified to use the questionnaire. The identified study candidates were approached to participate in the study during their follow up in HKL. Study respondents were explained their rights as participants, such as the confidentiality of their information, the right to withdraw from the study at any time during the interview processes and other rights of the patients. The next step for the study candidate is to sign the consent form for confirmation to participate in the study. The step after the administration of medical information followed by socio-demographic questionnaires, EORTC QLQ- C30, Brief COPE, VAS-P, SISS, MINI and finally the PHQ9 questionnaires. Patients were asked to respond to questionnaires read by the researcher. The duration of interview was 60 to 90 minutes for each patient.

5.2.International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)

The MINI questionnaire was developed according to DSM-IV and International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) criteria and has 96% sensitivity and 88% specificity (D. V. Sheehan, et al., 1997). The disorders were determined based on “yes” or “no” answers to the questions on the MINI (D. Sheehan, et al., 2009). The interviewer was trained to use the MINI by senior psychiatrists who had experience and were certified in using the MINI. In a Malaysian community setting, the Malay version has been shown to have good reliability with (0.67 to 0.85)

5.3.EORTC-QOL-30 questionnaire

The questions appear in likert scale format with answers as follows: “Not at all”, “A little”, “Quite a bit” and “Very much”. The scales range from 1 to 4 except for the global health status scale, which has 7 points ranging from 1 (“very poor”) to 7 (“excellent”) (Aaronson, et al., 1993). The EORTC-QOL-30 questionnaire has been pre-tested and validated. This disease-specific questionnaire is used to evaluate the quality of life of cancer patients. The questionnaire comprised of four languages including English, Malay, Mandarin and Tamil, was used in the study (Aaronson, et al., 1993; Mustapa & Yian, 2007). The Malay version had been validated among Malaysian cancer patients and it has internal consistencies for Global Health Status (0.91), Functional domains (0.50-0.89) and Symptoms domains (0.75-0.99) and the sensitivity of the scale found in all the domains (Yusoff, Low, & Yip, 2014).

5.4.Brief COPE

The questionnaire is composed of 14 subscales of specific coping styles in response to difficult and stressful life events. Each scale is associated with two test items. Each item was rated as follows: 1 = “I usually don’t do this at all”; 2 = “I usually do this a little bit”; 3 = “I usually do this a medium amount”; and 4 = “I usually do this a lot.” The Brief COPE questionnaire has sufficient validity (Carver & Charles, 1997; Schulz & Schwarzer, 2004)and reliability (Carver & Charles, 1997). Both English and Malay versions of the Brief COPE have good validity and reliability among the Malaysian population. Internal consistencies for the scale ranged from 0.25 to 1.00 and the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient ranged from 0.05 to 1.00. The sensitivity was ranged from 0 to 0.53 (N Yusoff, WY Low, & CH Yip, 2009; N Yusoff, WY Low, & CH Yip, 2009).

5.5.PHQ 9

It is comprised of nine questions and it is rated according to a two week time frame of symptoms on a scale from 0 to 3: 0 = not at all; 1 = several days; 2 = more than half the days; 3 = nearly every day. The final question is rated for difficulties with regards to problems, i.e., 1 = not difficult at all; 2 = somewhat difficult; 3 = very difficult; 4 = extremely difficult. The PHQ-9questionnaire has good internal reliability and validity (Lowe, Kroenke, Herzog, & Gräfe, 2004)and the Malay version had sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 82% (Sherina, Barroll, & Goodyear-Smith, 2012).The PHQ 9 comprised of nine questions and it is rated according to a two week time frame of symptoms on a scale from 0 to 3: 0 = not at all; 1 = several days; 2 = more than half the days; 3 = nearly every day. The final question is rated for difficulties with regards to problems, i.e., 1 = not difficult at all; 2 = somewhat difficult; 3 = very difficult; 4 = extremely difficult. The PHQ 9 scores were computed and classified according to symptoms scores as follows: (0-9) = normal to mild symptoms, (10-14) = moderate symptoms, (15-19) = moderately severe symptoms and (more than 20) = severe symptoms (Lowe, et al., 2004).

.

5.6.Data collection and statistical analysis

Important clinical information such as diagnosis and disease stage were gathered from the participants and confirmed with medical records from the hospital. The structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the inter -relationships between quality of life, coping styles, MDD and anxiety disorders the patients. Data analysis was conducted using AMOS version 24.

In SEM data analysis, there are several condition to be met such as normality and adequate number of sample size. The data should be normal in the SEM model to fulfill the criteria for assumptions and if the data is not normal, this will leads to violation of the assumption (Sharma, 1996). The adequate number of sample size in SEM is important to have stronger covariance and correlations. If the sample size is smaller it will generate less stable covariance and correlations, less power to identify path coefficients which is significant and it has capability to lead to instability (sample error) in the covariance matrix, which will leads to inadmissible solutions and poor goodness-of-fit indices (Kline, 2005; Quintana & E., 1999; Tabachnick& Fidell2001). The sample size for SEM is depending on the complexity of a model. Some experts have recommended by using a ratio in the determination of samples size for instance a ratio of 3 or 5 participants for each parameter that used in the SEM model (Bentler, 1990; Bollen & R., 1990 ). Other expert has stated the adequate number of sample size for SEM using maximum likelihood estimation could be from 100 and above samples size (J. F. Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Due to the target participants were considered hard to reach group, minimum of 100 participants were targeted for this objective. The model fitness would be evaluated after obtaining the data for analysis to confirm a sample of 100 participants was adequate to answer the objective.

Several fit indices were applied in the analyses to measure the goodness of fit of the SEM model. The statistics included chi- squared statistics, with a desired value of p<0.05, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with a desired value of less than 0. 07, the Tucker and Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) with desired values of greater than 0.95 (J. J. F. Hair, Black, Babin, & Rolph, 2010 ; Kline, 2011 ). Garver and Mentzer state that for a good model fit, the Chi-square normalized by degrees of freedom should be (χ̰2 /df) ≤ 3, goodness of fit index (GFI) > 0.9, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) > 0.8, non-normed fit index (NNFI)/TLI> 0.9, comparative fit index (CFI) >0.9 and root mean RMSEA should not exceed 0.08 (Garver, 1999). The p-value in the analysis should not be significant. TLI, and CFI ≥ 0.8 is good enough for SEM model (M. J. F. Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 2009; Mystakidou, et al., 2005). Therefore several fit indices were applied in the analyses to measure the goodness of fit of the SEM model such as Chi-square normalized by degrees of freedom, (χ̰2 /df)≤3, p>0.05, RMSEA≤0.08, TLI≥0.08 and CFI ≥0.95 (Garver, 1999).

5.7.Inclusion criteria

The participants were selected based on four main inclusion criteria. First, the participants must be diagnosed with neurological disorder. All stages of neurological disorders patients with good conscious level were included in the study. Second, the age of the participant must be at least 18 years. Third, the participants in the study should be able to understand Malay, English, Mandarin or Tamil. Finally, the participant must be conscious and able to be interviewed.

5.8.Exclusion criteria

There are some exclusion criteria to be considered in this study in order to prevent biases. First, participants were excluded from the study if the patient wants to withdraw from the study. Second, if participants who are mentally disabled such as mentally distorted were eliminated from the study. Third, participants with pain and not able to respond and requires immediate treatment were excluded. Fourth, if the participants were less than 18 years old were excluded from the study.

.

5.9.Ethics approval

Ethics approval sought from Human Research Ethics Committee, UniversitiSains Malaysia (FWA Reg No: 00007718; IRB Reg. No: 00004494) (USM/JEPeM/16050178) and Medical Research & Ethics Committee (MREC) at the Ministry of Health (MOH) (NMRR-16-1134-29874 (IIR).

6.Findings

6.1.Socio-demographic characteristics of brain disorder respondents

The study had a response rate of 93.5%.Table 01shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

6.2.Clinical characteristics of neurological disorder respondents

Table

6.3.SEM model 1

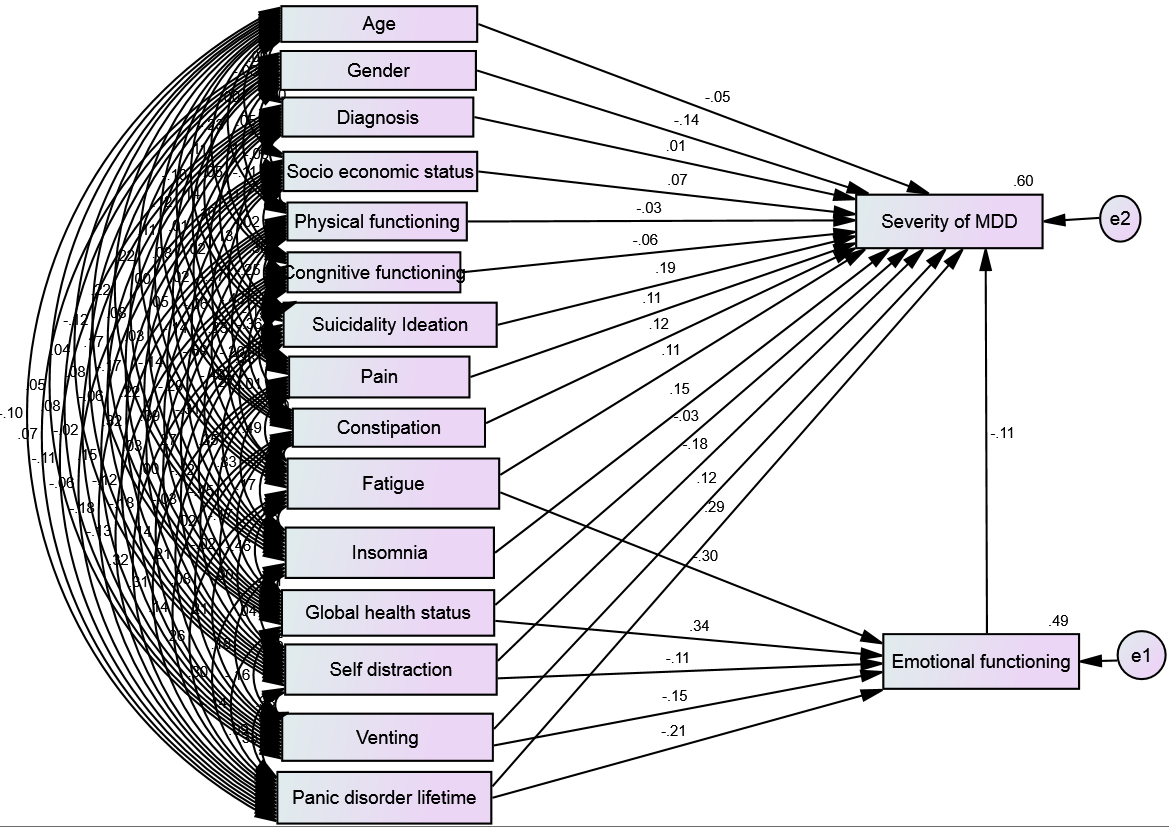

The analysis of the structural model is conducted by first testing the hypothesis. There are 21 hypothesized paths displayed in Table

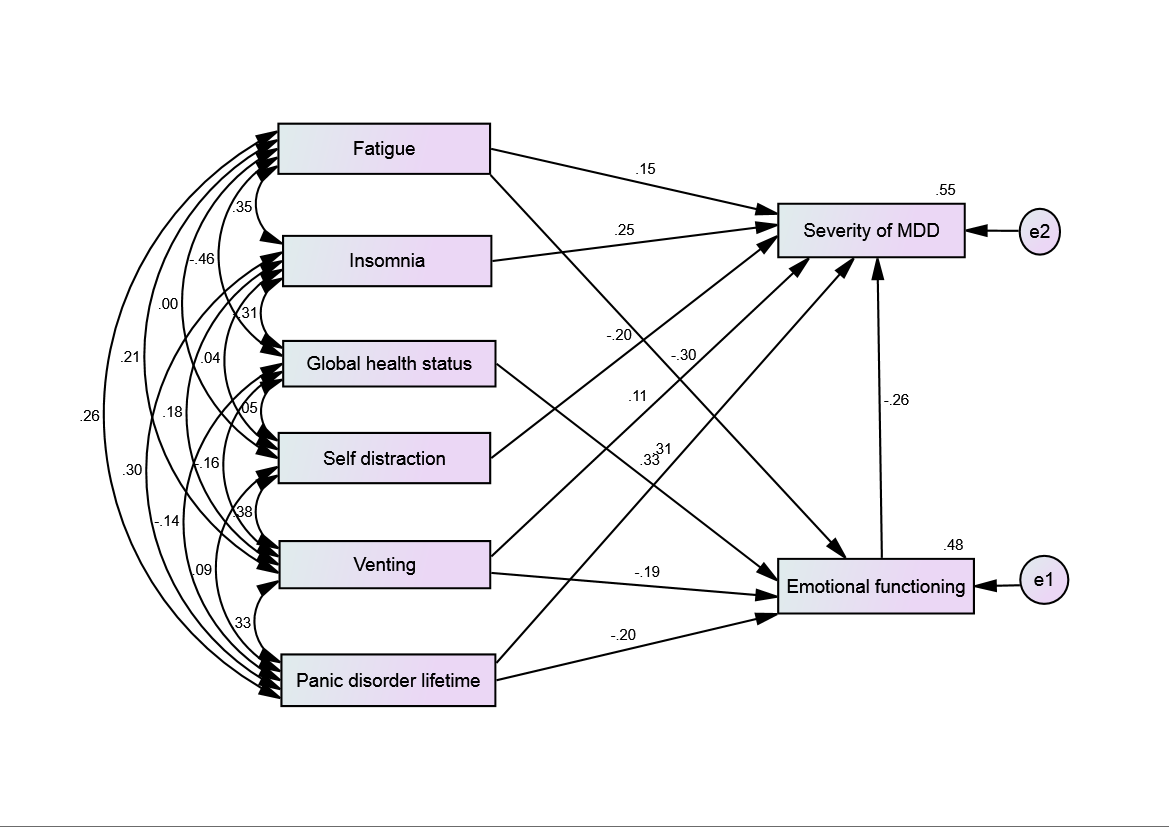

6.4. SEM model 2

Based on an examination of goodness-of-fit indices structural model 2 appears to have a better fit compared to previous models. Based on an examination of goodness-of-fit indices structural model 2 appears to have a better fit compared to previous models. The multivariate normality kurtosis was 6.174 with c.r = 2.440 obtained in this SEM model. Chi-square normalized by degrees of freedom, (χ̰2 /df) =1.086, p= 0.353.

The RMSEA was 0.03, TLI = 0.988 and CFI =0.999 were obtained in the study. All 8 paths out of 10 paths were significant with p-values less than 0.05 (two-tailed) with R2 values ranging from 0.48 to 0.55 which indicates that the variance explained ranged from 48% for emotional functioning to 55% for severity of depression.

The insomnia and panic disoder lifetime have positive relationship with severity of MDD. The self distraction coping styles has negative relationship with severity of MDD (p=0.005). The fatigue (p<0.001), venting (p=0.015) and panic disorder lifetime (p = 0.010) were found to have a negative relationship with emotional functioning score while global health status has positive relationship with emotional functionig (p < 0.001). Emotional functioning was found to have significant negative relationship with severity of MDD (p=0.03). (Fig 2, Table

A bootstrap method was applied with 500 usabale samples and it shows similar fit indices as in model 2 and the p-values are statistically significant for the parameters as shown in the table (Table

6.5.Discussion

In the path analysis of neurological disorder (brain tumour/brain disorder) patients,the main contributing factors of severity of MDD were emotional functioning, insomnia, self distraction coping styles and panic disoder lifetime. The emotional functioning of the patients were effected by the fatigue, global health status, venting coping styles and panic disorder lifetime and this eventually leads to increased severity of MDD. These results are in agreement with those of other studies and found that depression is associated with emotional, social functioning, poorer physical (Mystakidou, et al., 2005; Pamuk, et al., 2008; Smith, Gomm, & Dickens, 2003) role (Pamuk, et al., 2008), cognitive (Pamuk, et al., 2008; Smith, et al., 2003), and global health status (Smith, et al., 2003). The inverse correlation between quality of life score with depression and anxiety was found in a previous study of cancer patients (Montgomery, Pocock, Titley, & Lloyd, 2002).

The insomnia increases the MDD severity in this study. Symptoms such as sleep disturbance, appetite loss, financial difficulties (Mystakidou, et al., 2005), fatigue and nausea (Smith, et al., 2003) were associated with depression among the cancer patients. This patient subgroup had high levels of pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance and depression and reported poor functional status and low quality of life (Dodd, Cho, Cooper, & Miaskowski, 2010). Smith et al reported that in symptomology, the MDD had positive relationships with fatigue, insomnia, nausea/vomiting, appetite loss, diarrhoea, financial difficulties, dyspnoea and constipation (Smith, et al., 2003).

In another study of cancer patients, patients who were identified as more fearful of disease recurrence scored worse on the quality of life factors, especially in emotional functioning, fatigue, financial difficulties and enjoyment of food (Franssen, et al., 2009). Similarly the current study showed that MDD severity found to be increased with anxiety disorder such as panic disorder life time among the patients with brain tumour/brain disorder.

The severity of MDD found to be reduced if the patients applied self distraction coping styles and have better emotional functioning in the current study.Activities to distract oneself from the stressful event are known as distraction coping style. Behaviors such as doing physical activities, watching television, reading, or taking part in pleasurable events are the examples of the distraction coping styles. The person who are applying the self distraction coping styles always cope without directly solving the problem and it always categorized as an accommodative or secondary control coping tactic (Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000; Skinner & Wellborn, 1994; Walker, Smith, Garber, & Van Slyke, 1997).

In a recent study on the inter-relationship between anxiety and depression among the multiple sclerosis patients, it was found that the anxiety is a strong significant predictor for the depression. Both the anxiety and depression accessed by the self-administered HADS questionnaire.Path analysis was utilized for the strength of the direct and indirect relationships between the variables of interest. The depression is a dependent variable for the path analysis while the anxiety showed that it has both direct and indirect effects towards the depression. The anxiety is indirectly regulated by the two domains such as “functional status” and the “unregulated Emotion” towards the depression. The study found an insignificant Chi-squared test (χ 2 (2) = 4.12, p = .13) and good fit of the model with RMSEA=0.075, the CFI = 0.98. The SEM pathway explains about 46% of the variance of depression. The study has accessed on the mood, emotional processing and coping and to analyze how anxiety affects coping, emotional processing, emotional balance and depression. The study also found the gender and functional only displayed a minimal role. The researcher found the model explained almost half of the variance of depression (R 2 = .46)(Gay, et al., 2017).

The severity of MDD found to be reduced if the patients applied self distraction coping styles and have better emotional functioning in the current study.Activities to distract oneself from the stressful event are known as distraction coping style. Behaviors such as doing physical activities, watching television, reading, or taking part in pleasurable events are the examples of the distraction coping styles. The person who are applying the self distraction coping styles always cope without directly solving the problem and it always categorized as an accommodative or secondary control coping tactic (Connor-Smith, et al., 2000; Skinner & Wellborn, 1994; Walker, et al., 1997).

Two types of coping styles were found among the head and neck cancer patients such as emotion-oriented coping strategies or problem oriented coping strategies. The study reported that the patients with problem-oriented coping strategies have better adjustment and improved quality of life compared to patient with emotion-oriented coping styles having more anxiety and depression (Chaturvedi SK, Prasad KM, Senthilnathan SM, Premlatha BS,1996 ). Study by Daries et al noted that the coping ability were constantly challenged among the cancer patients because of cancer severity and its treatment that often creates severe stressful situations that eventually causes difficulties in maintaining an optimal adjustment (Razavi, et al., 1996).In longitudinal studies of late stage cancer patients, it is important to diminish depression and support their spiritual and overall life satisfaction (Rabkin, McElhiney, Moran, Acree, & Folkman, 2009). Interestingly optimistic characteristics cancer patients have reduced health-related worries and reduced level of depression and anxiety (Deimling, Bowman, Sterns, Wagner, & Kahana, 2006). The more depressed and anxious cancer patients had drastic discontinuation of positive lifestyles (Sharpley, Bitsika, & Christie, 2009). The treatment regimen was associated with toxicity and overall mood disorder, anxiety or adjustment disorder and increased patients’ length of the hospital stay (Prieto, et al., 2002). Therefore, early identification of patients with poor coping styles are important and the patients should take an initiative to increase their well-being, thus increasing chances of their own survival rate and prevent cancer relapse (Koehler, Koenigsmann, & Frommer, 2009).

Conclusion

The main contributing factors of severity of MDD were fatigue, insomnia, venting coping styles and panic disoder lifetime. The emotional functioning of the patients were effected by the fatigue, venting coping styles and panic disorder lifetime and this eventually leads to increased severity of MDD. A better understanding of the role of quality of life and coping styles on depression and anxiety would provide an insight to clinician, health psychologist, psychiatrist, and counselor in this country to implement cost-effective treatments.

Acknowledgement

The study supported by USM Short Term Grant, Project no: 304/PPSP/6315007 and Priscilla Das has been given a MyBrain15-MyPhd scholarship from Ministry of Education of Malaysia.

References

- Aaronson, N.K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N.J. (1993). The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. . Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85, 365-376.

- Arber, A., Faithfull, S., Plaskota, M., Lucas, C., & de Vries, K. (2010). A study of patients with a primary malignant brain tumour and their carers: symptoms and access to services. Int J Palliat Nurs, 16(1), 24-30.

- Ashbury FD, Findlay H, Reynolds B (1998). A Canadian survey of cancer patients’ experiences: Are their needs being met? J Pain Symptom Manage 16, 298-306.

- Association., A. P. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: DSM-IV-TR®: American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association.

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin 107: 238-246.

- Bollen KA, Stine R (1990). Direct and indirect effects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociological Methodology, 20, 115-140.

- Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basics concepts, applications and programming. .

- Chatur, & Charles, S. (1997). You want to Measure Coping But Your Protocol's Too Long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92.

- Chaturvedi, S.K., Shenoy, A., Prasad, K.M., Senthilnathan, S.M., Premlatha, B.S. (1996 ). Concerns, coping and quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. , 4(3), 186-190.

- Connor-Smith, J. K., Compas, B. E., Wadsworth, M. E., Thomsen, A. H., & Saltzman, H. (2000). Responses to stress in adolescence: measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. J Consult Clin Psychol, 68(6), 976-992.

- Deimling, G. T., Bowman, K. F., Sterns, S., Wagner, L. J., & Kahana, B. (2006). Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. [Article]. Psycho-Oncology, 15(4), 306-320.

- Dhandapani, M., Gupta, S., Mohanty, M., Gupta, S. K., & Dhandapani, S. (2017). Prevalence and Trends in the Neuropsychological Burden of Patients having Intracranial Tumors with Respect to Neurosurgical Intervention. Annals of Neurosciences, 24(2), 105-110.

- Dodd, M. J., Cho, M. H., Cooper, B. A., & Miaskowski, C. (2010). The effect of symptom clusters on functional status and quality of life in women with breast cancer. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 14(2), 101-110.

- Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Dikshit, R., Eser, S., Mathers, C., Rebelo, M.,... Bray F. (2015). Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer, 136(5), E359-386.

- Franssen, S. J., Lagarde, S. M., Van Werven, J. R., Smets, E. M. A., Tran, K. T. C., Plukker, J. T. ML;... de Haes, H. C. J. M. (2009). Psychological factors and preferences for communicating prognosis in esophageal cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 18(11), 1199-1207.

- Garver, M. S. a. M., J.T. (1999). Logistics research methods: Employing structural equation modeling to test for construct validity, Journal of Business Logistics,. 20, 1 33-57.

- Gay, M.-C., Bungener, C., Thomas, S., Vrignaud, P., Thomas, P. W., Baker, R;...Whittlesea A (2017). Anxiety, emotional processing and depression in people with multiple sclerosis. [journal article]. BMC Neurology, 17(1), 43.

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis.5th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall International,Inc.

- Hair, J. J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Rolph, E. A. (2010 ). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th Edition) 7th Edition.

- Hair, M. J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

- Holmes-Smith, C. E. C., L. (2006). Structural equation modelling: from the fundamentals to advanced topics, School Research, Evaluation and Measurement Services, Education & Statistics Consultancy, Statsline.

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Kline, R. B. (2011 ). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, Third Edition (Methodology in the Social Sciences).

- Koehler, M., Koenigsmann, M., & Frommer, J. (2009). Coping with illness and subjective theories of illness in adult patients with haematological malignancies: Systematic review. [doi: DOI: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.09.014]. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 69(3), 237-257.

- Lienard, A., Merckaert, I., Libert, Y., Delvaux, N., Marchal, S., Boniver, J;...Razavi D. (2006). Factors that influence cancer patients' anxiety following a medical consultation: impact of a communication skills training programme for physicians. Ann Oncol, 17(9), 1450-1458.

- Lienard, A., Merckaert, I., Libert, Y., Delvaux, N., Marchal, S., Boniver, J;...Razavi D. (2008). Factors that influence cancer patients' and relatives' anxiety following a three-person medical consultation: Impact of a communication skills training program for physicians. Psycho-Oncology, 17(5), 488-496.

- Lim, G., Rampal, S., & Halimah, Y. (2008). Cancer incidence in Penisular Malaysia, 2003-2005. National Cancer Registry, Kuala Lumpur.

- Lowe, B., Kroenke, K., Herzog, W., & Gräfe, K. (2004). Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). [doi: DOI: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8]. Journal of Affective Disorders, 81(1), 61-66.

- Montgomery, C., Pocock, M., Titley, K., & Lloyd, K. (2002). Individual quality of life in patients with leukaemia and lymphoma. [Article]. Psycho-Oncology, 11(3), 239-243.

- Mukhtar, F., Bakar., A. K. A., Junus., M. M., Awaludin., A., Aziz., S. A., Midin., M;.... Noor Ani Ahmad (2012). A preliminary study on the specificity and sensitivity values and inter-rater reliability of Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) in Malaysia. ASEAN J Psychiatry 13, 157-164.

- Mustapa, N., & Yian, L. G. (2007). Pilot-testing the Malay version of the EORTC questionnaire. Singapore Nursing Journal, 34(2), 16-20.

- Mystakidou, K., Tsilika, E., Parpa, E., Katsouda, E., Galanos, A., & Vlahos, L. (2005). Assessment of Anxiety and Depression in Advanced Cancer Patients and their Relationship with Quality of Life. [Article]. Quality of Life Research, 14(8), 1825-1833.

- Pamuk, G. E., Harmandar, F., Ermantaş, N., Harmandar, O., Turgut, B., Demir, M;....Vural, O. (2008). EORTC QLQ-C30 assessment in Turkish patients with hematological malignancies: association with anxiety and depression. Annals of Hematology, 87(4), 305-310.

- Parkin, D. M., Whelan, S. L., & FerlanJ. (2005). Cancer incidence in five continents. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, vol. I to VIII. IARC Cancerbase No 7.

- Price, T. R., Goetz, K. L., & Lovell, M. R. (2007). Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Brain Tumors. In: Yudofsky SC, Hales RE, editors. (The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences 5th ed. Arlington, VA ed.): American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Prieto, J. M., Blanch, J., Atala, J., Carreras, E., Rovira, M., Cirera, E., (…) Gasto C (2002). Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20(7), 1907-1917.

- Quintana, S. M., & Maxwell, S. E. (1999). Implications of recent developments in structural equation modeling for counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 27(4), 485-527.

- Rabkin, J. G., McElhiney, M., Moran, P., Acree, M., & Folkman, S. (2009). Depression, distress and positive mood in late-stage cancer: A longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology, 18(1), 79-86.

- Razavi, D., Allilaire, J., Smith, M., Salimpour, A., Verra, M., Desclaux, B., Blin, P. (1996). The effect of fluoxetine on anxiety and depression symptoms in cancer patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 94, 205 - 210.

- Schulz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2004). Long-term effects of spousal support on coping with cancer after surgery. [Article]. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 716-732.

- Sharma, S. (1996). Applied multivariate techniques. .

- Sharpley, C. F., Bitsika, V., & Christie, D. R. H. (2009). Understanding the causes of depression among prostate cancer patients: Development of the Effects of Prostate Cancer on Lifestyle Questionnaire. Psycho-Oncology, 18(2), 162-168.

- Sheehan, D., Janavs, J., Harnett-Sheehan, K., Sheehan, M., Gray, C., Leucrubier, Y., Dunbar G, C. (2009). M.I.N.I Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version 6.0.0 DSM-IV.

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Harnett-Sheehan, K., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Bonora, L. I., Dunbar G, C. (1997). Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): According to the SCID-P. European Psychiatry 12, 232-241.

- Sherina, M. S., Barroll, F., & Goodyear-Smith, M. ( 2012). Criterion validity of the PHQ-9 (Malay version) in a primary care clinic in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia 67 (No 3 June).

- Skinner, E. A., & Wellborn, J. G. (1994). Coping during childhood and adolescence: A motivational perspective. In: Featherman D, Lerner. R, Perlmutter M, editors. . Life-span development and behavior. NJ: Erlbaum; Hillsdale,, 12(2), 91-133.

- Smith, E. M., Gomm, S. A., & Dickens, C. M. (2003). Assessing the independent contribution to quality of life from anxiety and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Palliative Medicine, 17(6), 509-513.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S (2001). Using multivariate statistics 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Walker, L. S., Smith, C. A., Garber, J., & Van Slyke, D. A. (1997). Development and validation of the pain response inventory for children. . Psychological Assessment, 9, 392–405.

- Yusoff, N., Low, W., & Yip, C. (2014). The Malay Version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ C30): Reliability and Validity Study. The International Medical Journal of Malaysia, 9(2).

- Yusoff, N., Low, W., & Yip, C. (2009). Reliability and Validity of the Brief COPE Scale (English Version) Among Women with Breast Cancer Undergoing Treatment of Adjuvant Chemotherapy: A Malaysian Study. Med J Malaysia, 65 41-44.

- Yusoff, N., Low, W., & Yip, C. (2009). Reliability and validity of the malay version of brief cope scale: a study on malaysian women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry, 18.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 May 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-061-7

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

62

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-539

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Rasalingam, K., Kueh, Y. C., Noorjan, K., Wan-Arfah, N., Naing, N. N., & Das*, P. (2019). Inter-Relationships Between Quality Of Life, Coping Styles, Anxiety And Depression. In M. Imran Qureshi (Ed.), Technology & Society: A Multidisciplinary Pathway for Sustainable Development, vol 62. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 92-108). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.05.02.9