Abstract

In the contemporary word, the practice of using consumers as a group to boycott product or services has been an effective major tool for protesting, which is significantly expected to continue increasing in the coming years due to its recent trend? Based on this, the role of susceptibility to interpersonal influence (SII), animosity and perceived egregiousness on the consumers’ willingness to boycott USA products and companies supporting Israel is examined in this study with regards to the Malaysian Muslim youth. In order to achieve the aim of this study, data from 402 selected samples were collected, in which the use of descriptive analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and AMOS were all employed for this study. The result of the analysis shows that the Malaysian Muslim youth’s susceptibility to interpersonal influence, animosity and perceived egregiousness anteceded in their willingness to boycott, thereby serve as the basics reasons towards boycott participation. The findings also show a significant positive relationship between susceptibility to interpersonal influence, animosity and perceived egregiousness among the Malaysian Muslim youth. Also, an important theoretical contribution of susceptibility to interpersonal influence literature is made in this study, by making the construct as an antecedent of consumers’ willingness to boycott. Finally, the results of this study provide an extension in understanding the factors that affect consumer willingness to boycott, guidelines for policy makers, suggestions for regulators, and practical solutions based on the model tested for managers.

Keywords: “Malaysian Muslims’ Youth”“Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influence”“Animosity”“Perceived Egregiousness”“Consumer’s Willingness to Boycott”

Introduction

Studies have shown that the concerns of what is important to consumers in a product or services influence their behavior on how they perceive and act in their choice to use such products or services. As stated by John and Klein (2003), consumer boycott occurs when significant numbers of them intentionally stop purchasing a particular product, or receiving a service simultaneously, which may not be related to a single reason. As a result, a series of studies dedicated to investigate on consumer boycott have been carried out mostly in developed nations, however only a few of such has been done in developing Islamic nations, such as Malaysia. Even the few studies found in literature only focused primarily on religious beliefs in the context of Saudi Arabia (Al-Hyari, Alnsour, Al-Weshah, & Haffar, 2012), psychological motivations in the context of Malaysia (Abdul-Talib, Asmat-Nizam, 2012), and the effect of religiosity and animosity on the purchase intentions of Malaysians (Ahmed, Anang, Othman, & Sambasivan, 2013). There are limited studies conducted on factors that could influence boycott from young Malaysians’ perspective as proposed in this study.

Although some general studies have been carried out on the boycott concept, such as (Smith & Li, 2010; Jill Gabrielle Klein, Smith, & John 2004; Ahmed et al. 2013), but a study has yet to be conducted on the consumer susceptibility level to interpersonal influence (SII) and its role in boycott participation. The reason for this is that, Malaysians have been known to practice the culture of collectivism (Noordin, 2009). In view of this, the collective culture practiced by Malaysians make them to be more inclined towards the opinions of others, because collective orientations lay significant emphasis on the importance of group as opposed to that of the individualism. Owing to this, the practice could be used as a progress via consumer rights by young Malaysians on global call for the boycotting of Israeli products/companies, because of the country’s attack on the Palestinians. This is because, there has been increasing attention in the past decades in Malaysia towards boycotting the USA products and companies that support Israel in the war against the Palestine. As a result, this study attempts to examine the role of susceptibility to interpersonal influence, animosity and perceived egregiousness of Malaysian Muslim youth and their willingness towards boycotting American products and companies that support Israel.

Problem Statement

Over centuries, consumer boycott has been a phenomenon that exists in the market, in which it is now a continuous menace that businesses and firms are experiencing (Smith & Li, 2010). Furthermore, the act of consumers boycott also leads to sales loss, tarnishes brand image and contributes to loss of customers because products offered by rival firms are normally purchased by consumers during the period of boycott (John & Klein, 2003). This is why such act can have devastating effects on sales, corporate reputations, brand images and stock prices (Al-Hyari et al., 2012; Dekhil, Jridi, & Farhat, 2017; Abdul-Talib & Abdul-Latif, 2015).

Also, the effects of SII on decision-making process that have been extensively studied in consumer behavior and marketing literature by Bearden, Netemeyer & Teel (1989) make this study significant to be explored because there is still no other research that examined the overall SII role on consumer boycott yet. Hence it is imperative to investigate the role of SII in the context of a developing nation, particularly in Malaysia, as this factor may likely to be significant due to the society culture of collectivism (Noordin, 2009). The result of this study is hoped to affect the Malaysian perceptions and animosity towards USA companies/nations supporting Israel against Palestine, leading to boycotting inclination towards those companies.

Overall, factors motivating individual boycott decisions have remained largely untouched (Hoffmann & Müller, 2009; Barakat & Moussa 2017), which have caused lack of understanding among marketing managers and policy makers in the subject of consumer protect behavior and what factors influence consumer boycott (Yuksel & Mryteza, 2009). This largely culminates to the lack of awareness among firm managers and NGOs of what elements motivate consumer boycott.

As stated earlier, Malaysia culture of collectivism maybe paramount in the achievement of a successful boycott, due to its characteristic which refers to a social pattern of closely-related individuals who perceive themselves as forming a part of one or more collective ideas, such as family, co-workers, tribe and nation. The set or groups are directed by the norms and duties laid down collectively and are inclined towards prioritizing their goals over individual desires, emphasizing their relationship to collective membership (Triandis, 1995). This idea is practiced by many nation, such as Asian countries, African countries and countries in South America in which the communities have greater tendency to remain in groups and as suggested by Noordin (2009), Malaysians practice a high level of collectivism.

Research Questions

Generally, research objectives are achieved after providing answers to research question. The following are the research questions of this study.

What is the relationship between susceptibility to interpersonal influence and animosity, and perceived egregiousness among Malaysian Muslim consumers’ youth?

Do animosity and perceived egregiousness affect willingness to boycott U.S. products and companies supporting Israel among Malaysian Muslim consumers’ youth?

Can model that examine the relationship of consumer willingness to boycott among Malaysian Muslim consumers’ youth, be built?

Purpose of the Study

The research objectives of this study are as follows:

4.1. To examine the impact of susceptibility by interpersonal influence on animosity and perceived egregiousness among Malaysian Muslim consumers’ youth.

4.2. To determine the influence of animosity, perceived efficacy and perceived egregiousness on the willingness to boycott among Malaysian Muslim consumers’ youth.

4.3. To propose and test a structural model that can be used to examine the relationship of consumers’ willingness to boycott product/company among Malaysian Muslim consumers’ youth.

Literature Review

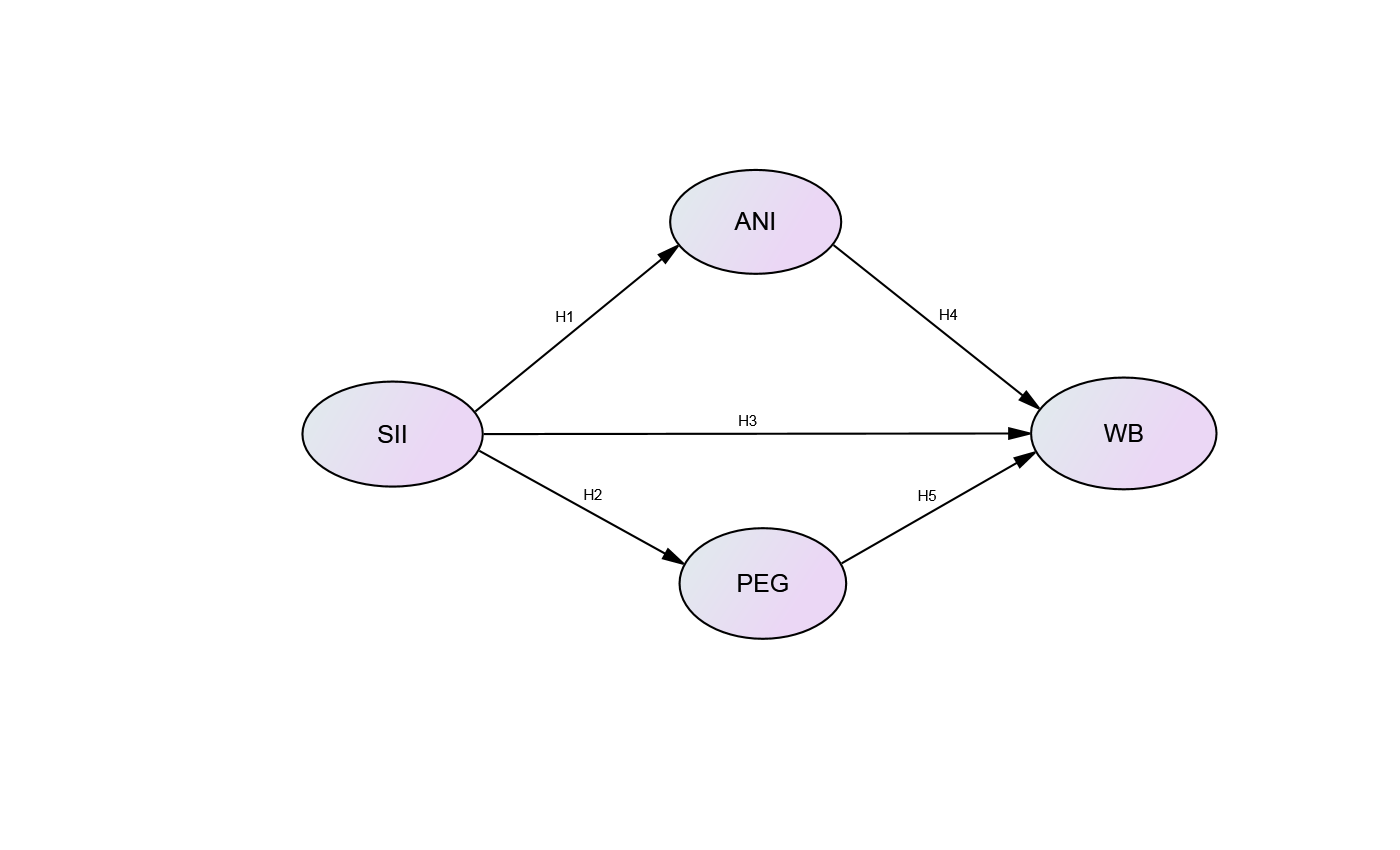

This study presents the determinants of the consumer willingness to boycott in the conceptual framework as designed in Figure

It is the shown in this study that the consumer’s susceptibility is influenced by interpersonal influence, and boycott antecedents, such as animosity and egregiousness of consumers. This would impact their inclination towards boycotting the USA products and companies that support Israel. Additionally, this study believes that the consumer susceptibility by interpersonal influence, animosity and perceived egregiousness of consumers can significantly impact their willingness towards the boycotting of USA products and companies that support the Israel against Palestine.

Consumer Willingness to Boycott (WB)

Generally, consumer boycott refers to a phenomenon in which customers at all levels stop purchasing a specific product/brand. Friedman (1985) stated that in the modern times, the act of convincing individuals (consumers) as a party’s/parties’ attempting to achieve a specific aims of stopping to buy a selected products in the market is considered boycotting. However, there are some related motivating factors that lead to boycott which have not been researched as mentioned by Hoffmann and Müller (2009). This caliber of studies is presumed to provide a clearer understanding to the reason behind consumers’ engagement/disengagement in boycotts (Klein et al. 2004; Hoffmann & Müller 2009; Braunsberger & Buckler 2011). However, some studies have identified the boycott decision among consumers, which largely hinges on several factors, such as personal factors (individual evaluation of the boycott operation and organization like perceived possibility of a successful boycott and perceived publicity of the boycott campaign) (Cissé-Depardon & N’Goala, 2009).

Susceptibility to Interpersonal Influence (SII)

Susceptibility by interpersonal influence among consumers arise due to the need of having their identification, in order to enhance the importance of self-image in the eyes of others through purchasing and utilizing separate products/brands that is in conformance of others’ expectations. Studies have shown that SII could be bi-dimensional (normative and informational SII). As stated, the normative SII represents the individual’s inclination to comply with social groups, with the expectation that such person will get rewarded without being punished, in which according to nature, it represents value of expression and utilitarian. While the information SII type represents the influence of one person to obtain information from another as a factual evidence (D’Rozario & Choudhury, 2000). Another reason why consumers take decisions to boycott a certain product or company is largely due to the fact that the consumers want to be accepted and respected by their peers, in order to steer themselves in a way that their societal members may frown upon. Additionally, as stated by Park and Yoon (2017) study suggested that susceptibility to normative influence has a significant relationship with consumer animosity.

However, studies have also shown that, not all consumers who perceive actions as egregious will eventually take part in a boycotting action (Klein et al., 2002; 2004). Although, in line with explaining SII, it is possible for them to follow their group under some situations, with egregiousness level arising, especially with the participation of quite a large number of people. In other words, there is higher tendency for firms to be affected by high consumer SII due to the greater tendency of others influences belief that the firm actions are egregious. Orth and Kahle (2008) proved that the higher the susceptibility to normative influence, the greater the inclination towards social benefit to a brand because of the desirous nature of an individual to enhance the person’s image compliance to other’s expectations.

In a different study conducted by Khare (2014), normative and informative influences were discovered to be the predictors of ecological consciousness of purchase behavior in the aspect of consumer susceptibility. Over all, as reviewed from several literatures in this study regarding the relationship of consumers’ willingness to boycott and influence, most of the previous studies indicated that customers’ SII susceptibility interpersonally has a positive significant in their decisions and behavior (Orth & Kahle, 2008). In view of this, the present study proposes that there is a perceive greater animosity of the Malaysian Muslim youth’s susceptibility interpersonally (normative and informative), making them to be more inclined to boycott USA products and companies that support Israel which could be egregiousness to firms. This act is believed to make the firms to adhere to social norms or to be accepted within their reference group. In other words, this study proposes the following hypothesis for testing:

H1: There is a positive relationship between susceptibility to interpersonal influence and the level of consumer animosity.

H2: There is a positive relationship between susceptibility to interpersonal influence and the level of consumers’ perceived egregiousness.

H3: There is a positive relationship between susceptibility to interpersonal influence and the level of consumer willingness to boycott.

Animosity (ANI)

Rose, Rose, & Shoham (2009) referred to consumer animosity as the significant negative emotions of consumers towards buying products from one nation/group that they feel hatred towards. Several studies on the relationship of animosity and product evaluations indicate the negative impact of consumer animosity on the tendency of consumers to purchase products from abroad (Ettenson & Klein, 2005; Narang, 2016; Cheah, Phau, Kea, & Huang, 2016). As a result, this study proposes that the animosity of Malaysian consumers’ youth has a positive influence on boycotting the USA products and companies that support Israel against Palestine. Therefore, this study proposes H4: There is a positive relationship between animosity and level of consumer willingness to boycott).

Perceived Egregiousness (PEG)

As such, the study of perceived egregiousness has been a common element in available literatures that focus on boycott, in which it has been identified as a primary driver or one of the main influence that predicts boycott participation (Klein et al., 2004). As found in many studies, the perceived egregiousness has been one of the top relevant factors that is influencing boycotting participation (Klein et al. 2004; Hoffmann & Müller 2009; Balabanis, 2013).

Furthermore, the egregiousness of the firm may spring a surrogate boycott, which might be due to their country of origin. Similarly, the egregious firm might be boycotted by retailers, wholesalers or related entities of products (John & Klein, 2003; Tyran & Engelmann, 2005). The boycott is used in expressing their dissatisfaction with the firm/country’s actions or policies (Braunsberger & Buckler, 2011). Hence, the present study’s findings are expected to be aligned with previous researches that supported the positive effects of perceived egregiousness to boycott on the part of the consumer. Therefore, this study proposes H5: There is a positive relationship between perceived egregiousness and level of consumer boycott.

Research Method

In order to achieve the objectives of this research, data collection was carried out for over five weeks by distributing survey questionnaires to students between the ages of 18-35, who enrol in two of Malaysian universities; University Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) and University Putra Malaysia (UPM). After which quantitative method of analysis was employed to analyse the data. The total questionnaires distributed for this study was 402 to all the students who hailed from all over Malaysia. All questionnaires were returned and considered suitable for the analysis. Additionally, the use of SPSS, Version 21, and AMOS Version 21 were employed for the data analysis. Also, this study adopts the constructs of previous literature and measurement of 7-point Likert scale, which ranged from 1 depicting strongly disagree to 7 depicting strongly agree. More specifically, the construct of Klein, Ettenson, & Morris, (1998) on consumer willingness items , and SII items were adopted including its modified version from the study of Bearden et al. (1989), vis a vis the animosity items model from Klein et al. (1998) and finally, perceived egregiousness items model were adopted from the following authors; Klein, John, & Smith, (2001); Braunsberger & Buckler (2011), and one item (PEG3) from the researchers.

Findings

The findings of this study considered the characteristics profiles of the respondents, such as their gender, education level, marital status, and income level. Firstly, findings show majority of the respondents (80%) are female students, while the remaining ones (20%) are male students. Based on this, the level of education of degree holders constituted 79%. In terms of the state 44.5% of them hailed from the central region (i.e., Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, and Perak), 23% from the eastern region (i.e., Kelantan, Terengganu, and Pahang), 19% from the southern region (i.e., Johor, Melaka and Negeri Sembilan), 9.5% from the northern region (i.e., Pulau Pinang, Kedah and Perlis) and lastly, 4% from Sabah and Sarawak.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

As stated earlier, the use of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was employed in this study in order to determine the relationship level of the observed variables, including the underlying factors. Basically, as suggested by Straub (1989), the EFA analysis was carried out in this study, in order to determine the validity of the items contained within the survey questionnaires. In which the data collected for this analysis were fit for the EFA based on several reasons, such as (i) the majority of the correlation coefficients scores were over 0.3, and (ii) the values of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) was higher than 0.60 (the cut-off value) – particularly SII KMO value is 0.778, PEG is 0.762, ANI is 0.844, and WB is 0.802. Finally, the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity achieved the statistical significance level required and confirmed the data appropriateness to be exposed to analysis (Pallant, 2005).

Moreover, it was discovered that the EFA value of SII reveals that the items employed for this study, i.e. SII11, SII12, and SII3 were successfully loaded on normative influence, items SII4, SII7 and SII8 was also successfully loaded on informational influence, in which items SII1, SII5, SII6, SII9 and SII10 were dropped owing to low factor loading. Therefore, the findings of this study can be said to be consistent with that of Bearden et al. (1989). In terms of the animosity items, the EFA shows that they were successfully loaded on a single component, with ANI1, ANI2, ANI3 and ANI4 being dropped owing to low factor loading. Similarly, the items of perceived egregiousness were loaded on one component, and the consumer willingness to boycott items was also loaded on one component, with WB4 deleted for higher value of Cronbach’s alpha. Finally, the help of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of SEM was employed to test the hypotheses proposed for this study.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

In the conceptual model of this study, the factorial structure of the constructs was confirmed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of AMOS, where the analysis considered four constructs and obtain measurement model obtained of x2=339.270, having 143 degrees of freedom with the following fit measurements; χ2 (CMIN/df) = 2.773, p= .000, GFI= .914; AGFI= .886; CFI= .946; IFI= .946; TLI= .935, RMSEA= .059. These show that the model is good enough as proposed earlier. Below Table

The SEM analysis using AMOS demonstrates Goodness-of-fit indices of; Chi –Square χ2 (CMIN) = 399.001, df = 144, Relative χ2 (CMIN/df) = 2.771, p .000, GFI = .899, CFI = .929, NFI= .894, IFI = .930, TLI = .916, RMSEA = .066.

Conclusion

Based on the aim of the study, the results obtained in this study have supported the effects in several ways. Firstly, the study examined the SII role in influencing consumers to boycott USA products and companies that support Israel whereby the opinions and perceptions of other referent arise, such as the effect of SII on animosity. The result of this construct supported the proposed relationship and is found to be consistent with the results of the study carried out by Park and Yoon (2017), who stated that susceptibility to normative influence has a significant relationship with the animosity of consumers, particularly Korean consumers and their animosity towards Japanese products. The meaning of this is that the desire of Malaysian Muslim youth to have animosity stems from their social network and the influence of their referent group (2010). Secondly, this study examined the effect of SII to perceived egregiousness and the findings show that the data of this study supported the proposed hypothesis. Based on this, Malaysian Muslim youth’s perception of egregiousness is also positively associated to their susceptibility to interpersonal influence, having a greater harmony between individual perception of egregious actions of the firms and the perception of fellow boycotters’ urge. Furthermore, as found in this study, the majority of previous studies noted that the opinions of others on individuals in making decisions has high level of significance (Bearden et al., 1989; Khare, 2014; Chang, 2015). This could mean that the dissatisfaction of Malaysian Muslim youth with the USA products and companies that support Israel, such as McDonald’s and Starbucks will steer clear of such products from the egregiousness of the company/country. Thirdly, this study examined effect of SII on consumer’s willingness to boycott, because consumers are influenced differently, as some are referent, while others do not to patronize foreign brands, thereby ending up in them boycotting such brands. Therefore, there exists a consistency with the report from Jamal and Shukor (2014), and Chang (2015) that there is a positive relationship between SII and consumer behavior, which in this case, boycotting of USA products and companies that support Israel against Palestine. Particularly, the susceptibility of the Malaysian youth to interpersonal influence impacts their boycott willingness of the USA products and companies that support Israel in Malaysia.

Fourthly, this study examined hypothesis that is related to the role of animosity on consumer’s willingness to boycott and findings obtained show support to developed hypothesis and is consistent with prior studies that reported the positive impact of consumer animosity on the willingness of consumers to purchase foreign products (in this case, to boycott foreign products) (Smith & Li, 2010; Cheah et al., 2016; Lee, Lee & Li, 2017). Fifthly, this study supported the relationship between perceived egregiousness and consumer willingness to boycott. This result is in line with those reported in prior studies, including Yilmaz and Alhumoud (2017). In view of this, the findings of this study indicate the importance of recognizing the Malaysian Muslim youth’s identification of the unsuitable participation in egregious actions of the Zionist Israel towards the Palestinians. In capping, it is evident that the Malaysian Muslim youth’s perception of firm’s egregious actions is positively related to their boycott inclination.

Contributions and Theoretical Implications of the Study

The current study has provided several contributions in the knowledge of consumers boycott and marketing. The result found that susceptibility to interpersonal influence (SII) directly affects perceived egregiousness. Similarly, the present study found overall SII of both normative and interpersonal influence, to positively affect animosity. Hence, this study has contributes to the body of literature by supporting the two relationship, which is the effect of overall SII on animosity.

In view of this, as discovered in the study of Smith Li (2010), the high animosity towards goods created in other countries led to a high level of willingness to participate in boycotting among consumers. Additionally, Ettenson and Klein (2005) found that participants believed that through boycotting of product, they can express their anger and are convinced that they will halt egregious behavior of firm/government. Furthermore, this study developed a perceived egregiousness construct by adding another item (PEG3), after which a high degree of internal consistency was obtained. As a result, the new item had a high loading of one construct based on the results of factor analysis that shows the item validity.

Managers of USA products and companies that support Israel against Palestine must be aware of the consumers’ offshore decisions, by considering it as a socially responsible act and that even consumers that are not affected may participate in the boycott practices, hence, the company must stop supporting Israel against the Palestine. In doing so, NGO managers and organizers of the boycott campaign in Malaysian may hire a spokespersons and referent groups to advertise and promote campaigns against those who patronize and consume the USA products and companies that support Israel.

Limitation and Future Work

The sole focus on the Malaysian Muslims youth without representing the whole Muslim community in other countries serves as the first limitation of this research. Therefore, future studies are suggested to collect the data from many countries by employing the use of cross-national studies. While the age limit of data gathered for this study, ranging from 18-35 years old may limit the evaluation of belief of this study. Based on this, further studies are suggested to be generalized with caution to other ethnic groups and ages as they possess different beliefs and characteristics. The last limitation of this study lies in the fact that USA products and companies that support Israel specifically fast-food restaurants is the sole focus of the present research, in which case, future study must examine implications on different categories of products (e.g., e-products or banking institutions).

References

- Abdul-Talib, Asmat-Nizam, S. (2012). The Willingness to Boycott Among Malaysian Muslims, (December 2013), 0–33.

- Ahmed, Z., Anang, R., Othman, N., & Sambasivan, M. (2013). To purchase or not to purchase US products: role of religiosity, animosity, and ethno-centrism among Malaysian consumers. Journal of Services Marketing, 27(7), 551–563.

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control (pp. 11–39).

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, Personality and Behavior. Mapping social psychology.

- Ajzen, I., & Madden, T. J. (1986). Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22(5), 453–474.

- Al-Hyari, K., Alnsour, M., Al-Weshah, G., & Haffar, M. (2012). Religious beliefs and consumer behaviour: from loyalty to boycotts. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 3(2), 155–174.

- Balabanis, G. (2013). Surrogate Boycotts against Multinational Corporations: Consumers’ Choice of Boycott Targets. British Journal of Management, 24(4), 515–531.

- Bearden, W. O., Netemeyer, R. G., & Teel, J. E. (1989). Measurement of Consumer Susceptibility To Interpersonal Influence. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 473–481.

- Braunsberger, K., & Buckler, B. (2011). What motivates consumers to participate in boycotts : Lessons from the ongoing Canadian seafood boycott. Journal of Business Research, 64(1), 96–102.

- Chang, S. H. (2015). The influence of green viral communications on green purchase intentions: The mediating role of consumers’ susceptibility to interpersonal influences. Sustainability (Switzerland), 7(5), 4829–4849.

- Cheah, I., Phau, I., Kea, G., & Huang, Y. A. (2016). Modelling effects of consumer animosity: Consumers’ willingness to buy foreign and hybrid products. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 30, 184–192. H

- Cissé-Depardon, K., & N’Goala, G. (2009). The Effects of Satisfaction, Trust and Brand Commitment on Consumers’ Decision to Boycott. Recherche et Applications En Marketing English Edition, 24(1), 43–66.

- Dekhil, F., Jridi, H., & Farhat, H. 2017. “Effect of religiosity on the decision to participate in a boycott”. Journal of Islamic Marketing Vol 8 (2): pp. 309–328

- D’Rozario, D., & Choudhury, P. K. (2000). Effect of assimilation on consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(4), 290–307.

- Ettenson, R., & Gabrielle Klein, J. (2005). The fallout from French nuclear testing in the South Pacific. International Marketing Review, 22(2), 199–224.

- Fischer, J. (2007). Boycott or Buycott? Malay Middle-Class Consumption Post -9/11. Ethnos, 72(1), 29–50.

- Friedman, M. (1985). Consumer Boycotts in the United state, 1970-1980: Contemporary Events in Historical Perspective.

- Hoffmann, S., & Müller, S. (2009). Consumer boycotts due to factory relocation. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 239–247. H

- Huang, Y., Phau, I., & Lin, C. (2010). Consumer animosity, economic hardship, and normative influence. European Journal of Marketing, 44(7/8), 909–937.

- Jamal, A., & Shukor, S. A. (2014). Antecedents and outcomes of interpersonal influences and the role of acculturation: The case of young British-Muslims. Journal of Business Research, 67(3), 237–245.

- John, A., & Klein, J. (2003). The Boycott Puzzle: Consumer Motivations for Purchase Sacrifice. Management Science, 49(9), 1196–1209.

- Khare, A. (2014). Consumers’ susceptibility to interpersonal influence as a determining factor of ecologically conscious behaviour. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 32(1), 2–20.

- Klein, J. G., Ettenson, R., & Morris, M. D. (1998). The Animosity Model of Foreign Product Purchase: An Empirical Test in the People’s Republic of China. Source Journal of Marketing, 62(1), 89–100.

- Klein, J. G., John, A., & Smith, N. C. (2001). Exploring Motivations for Participation in a Consumer Boycott, 44(1), 1–22.

- Klein, J. G., Smith, N. C., & John, A. (2004). Why We Boycott: Consumer Motivations for Boycott Participation. Journal of Marketing, 68(3), 92–109.

- Lee, R., Lee, K. T., & Li, J. (2017). A memory theory perspective of consumer ethnocentrism and animosity. European Journal of Marketing, 51(7/8), 1266–1285.

- Narang, R. (2016). Understanding purchase intention towards Chinese products: Role of ethnocentrism, animosity, status and self-esteem. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 32, 253–261.

- Noordin, F. (2009). Individualism-collectivism: A tale of two countries. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 7(2), 36–45.

- Orth, U. R., & Kahle, L. R. (2008). Intrapersonal Variation in Consumer Susceptibility to Normative Influence : Toward a Better Understanding of Brand Choice Decisions Intrapersonal Variation in Consumer Susceptibility to Normative Influence : Toward a Better Understanding of Brand Choice D. The Journal of Social Psychology, 148(4), 423–447.

- Overby, J. W., Gardial, S. F., & Woodruff, R. B. (2004). French versus American consumers’ attachment of value to a product in a common consumption context: A cross-national comparison. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(4), 437–460.

- Pallant, J. (2005). SPSS Survival Manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows (Version 12). Allen & Unwin.

- Park, J. E., & Yoon, S.-J. (2017). Antecedents of consumer animosity and the role of product involvement on purchase intentions. American Journal of Business, 32(1), 42–57.

- Rose, M., Rose, G. M., & Shoham, A. (2009). The impact of consumer animosity on attitudes towards foreign goods: a study of Jewish and Arab Israelis. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 26(5), 330-339.

- Smith, M., & Li, Q. (2010). The Boycott Model of Foreign Product Purchase : An Empirical test in China, 18, 106–130.

- Straub, D. W. (1989). Validating Instruments in MIS Research. MIS Quarterly, 13(2), 147-169.

- Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and Collectivism, Bouder, CO'. Westview Press. Wiltermuth, SS & Heath, C.(2009). Syn-chrony and cooperation. Psychological Science, 20, 1-5.

- Tyran, J. R., & Engelmann, D. 2005. “To buy or not to buy? An Experimental study of consumer boycotts in retail markets”. Economica. Vol 72 (285): pp. 1–16

- Yilmaz, H., & Alhumoud, A. (2017). Consumer Boycotts : Corporate Response and Responsibility, 7(3), 373–380.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 May 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-061-7

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

62

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-539

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Abdul Shukor, S., & Emhemad Tariki*, H. (2019). The Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness To Boycott Among Malaysıan Muslim Youth. In M. Imran Qureshi (Ed.), Technology & Society: A Multidisciplinary Pathway for Sustainable Development, vol 62. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 319-330). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.05.02.31