Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: Longitudinal Effects Of Emotional Regulation Moderated By Parental Support

Abstract

Problem Statement: Low parental support and emotional regulation difficulties have been associated with depression in adolescence. Attending to the Transactional Model, the interaction of these variables may influence an adaptive/non-adaptive trajectory. Research Questions: Concerning there are few studies about these variables interaction effects, it might be important to understand better what are the effects and the possible implications on adolescent depressive symptomatology. Purpose of the Study: The present longitudinal study analysed the parental support as a moderator on cognitive emotional regulation strategies effects on depressive symptomatology in adolescence, more specifically the moderating effects of mother support and father support perceived by the adolescent. Research Methods: A community sample consisted of 566 Portuguese adolescents (60.25% female), with ages between 13 to 17 years old, participated by completing self-response questionnaires, assessing in the first moment the cognitive strategies of emotional regulation and the parental support, and in a second moment, six months later, the depressive symptomatology. Findings: After controlling gender effects, there was only a significant moderating effect between mother support and acceptance emotional regulation strategy. In the present study, acceptance revealed as a maladaptive emotional regulation strategy, contrary to what was expected. Conclusions: The results suggested that when adolescents highly resort to acceptance in a maladaptive way, low levels of mother support may lead to an increase in the depressive symptomatology levels, compared to a high perception of support. This means that mother support might protect from developing depressive symptomatology when adolescents highly misuse acceptance.

Keywords: DepressionParental SupportEmotional RegulationAdolescence

Introduction

Studies by the World Health Organization (2017) show that the estimated number of people living with depression worldwide increased by 18.4% between 2005 and 2015, pointing to depression as one of the greatest causes of disability in the world. The high registry number of users with depressive disorders in Portuguese Primary Health Care (DGS, 2016) is in agreement with such data.

A review made by Costello, Copeland and Angold (2011) revealed an increase in the depression prevalence at the transition from childhood to adolescence, with the onset of depression at the second developmental stage being associated with a relatively stable and more severe course over time, with a greater risk of recurrence.

Erse et al. (2016) did a review of studies with non-clinical adolescent samples and found that 9.2% to 14% of adolescents suffer from moderate or severe depression, with a higher prevalence among girls.

In Portugal, Cardoso, Rodrigues, and Vilar (2004) verified in their study that 11.2% of the adolescents with 12 to 17 years old had depressive symptoms, with girls also showing a higher prevalence. This gender tendency has also been observed in other Portuguese studies (Duarte, Matos, & Marques, 2015; Ferreira, 2016; Gomes, Matos, Monteiro, & Mónico, 2015).

Depression has been conceptualized as involving difficulties in identifying emotions, to accept, tolerate and support the experience of negative emotions, and change adaptively the experienced emotions (Berking & Wupperman, 2012). According to the depression models concerning cognitive stress vulnerability, in the face of negative life events, individuals with maladaptive cognitive styles are more likely to develop depression (Hyde, Mezulis, & Abramson, 2008). A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies also revealed a significant relationship between negative coping styles and higher levels of depressive symptomatology (Cairns, Yap, Pilkington, & Jorm, 2014).

Emotional regulation corresponds to internal and transactional processes, which are consciously or non-consciously employed, with the objective of modulating the components of emotions and influencing experiences and emotional expressions (e.g. frequency, duration and intensity), being characterized by involving abilities such as inhibiting, delaying or modifying emotions or the way they are expressed, taking into account rules, goals or plans, thus facilitating adaptive social functioning (Larsen et al., 2013; Steinberg, 2005; Yap, Allen, & Sheeber, 2007; Thompson, 1994).

Garnefski, Kraaij, and Spinhoven (2001) developed the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) to evaluate cognitive emotional regulation strategies that can be used by adolescents when facing negative life events. The authors pointed out nine conceptually distinct strategies: self-blame; blaming others; rumination; catastrophizing; putting into perspective; positive refocusing; positive reappraisal; acceptance; and refocus on planning.

Several studies have demonstrated an association between cognitive emotional regulation strategies and depressive symptomatology in adolescence, with positive relationships with strategies like rumination, catastrophizing and self-blame, and negative relationships with more adaptive strategies, like positive reappraisal (d’Acremont & Van der Linden, 2007; Garnefski, Boon, & Kraaij, 2003; Garnefski, Hossain, & Kraaij, 2017; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2014; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2016; Garnefski, Kraaij, & van Etten, 2005; Garnefski, Legerstee, Kraaij, Van den Kommer, & Teerds, 2002; Kraaij & Garnefski, 2012; Kraaij et al., 2003; Öngen, 2010). Indeed, studies that analysed the factorial structure of CERQ verified a division between theoretically more adaptive strategies (e.g. putting into perspective, positive refocusing, positive reappraisal and refocus on planning) and less adaptive strategies (e.g. self-blame, blaming others, rumination and catastrophizing) (d’Acremont & Van der Linden, 2007; Garnefski et al., 2017; Garnefski, Kraaij, & Spinhoven, 2001; Öngen, 2010). In respect to the acceptance strategy, while some studies consider it as a more adaptive strategy (d’Acremont & Van der Linden, 2007; Garnefski et al., 2001), other studies verified that this strategy was positively associated with depressive symptomatology (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2016).

It’s also important to notice that emotional regulation is mainly developed in the context of the interactions between the child and his/her caregivers (Southam-Gerow, 2013). In this way, family environment and parenting styles play an important role in the emotional regulation strategies development, with parents influencing through affective induction, modelling, controlling the environment in which the child is inserted in order to limit, or not, the opportunity to experience the emotions, and teaching strategies to regulate them (Betts, Gullone, & Allen , 2009; Hilt, Armstrong, & Essex, 2012; Morris, Criss, Silk, & Houltberg, 2017; Morris, Houltberg, Criss, & Bosler, 2017; Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007).

Several studies found associations between higher levels of depressive symptomatology and insecure attachments between adolescents and their parents, while secure attachment was associated with a lower risk of developing depressive symptomatology in adolescence (Allen, Porter, McFarland, McElhaney, & Marsh, 2007; Armsden, McCauley, Greenberg, Burke, & Mitchell, 1990; Duchesne & Ratelle, 2014; Rawatlal, Kliewer, & Pillay, 2015).

Attachment relationships are influenced by the quality of family functioning in terms of factors such as availability of support, cohesion, communication and levels of conflict (Rawatlal et al., 2015). In fact, the literature has shown that a positive relationship with parents, characterized by high support, cohesion, acceptance, affection, communication, and parental availability, has been associated with several positive development indicators, such as fewer problems of internalization, externalization and substance use, fewer risky sexual behaviours, better school performance, and better social skills (Branje, Hale, Frijns, & Meeus, 2010; Ewing, Diamond, & Levy, 2015; Kenny, Dooley, & Fitzgerald, 2013; Zhou, Sandler, Millsap, & Wolchik, 2008).

Even though both mothers and fathers take a great impact on depressive symptomatology in adolescence (Sheeber, Davis, Leve, Hops, & Tildesley, 2007; Stice, Ragan, & Randall, 2004; Yap, Pilkington, Ryan, Jorm, 2014), a longitudinal study in a community sample of adolescents (Duchesne & Ratelle, 2014) found that attachment security to the mother, but not to the father, was associated with a lower risk for reporting moderate depressive symptoms, even though attachment security to the mother and to the father were correlated with each other.

The gender of the adolescent might also explain some differences related to the impact of the relationship quality on the development of depressive symptomatology. It was found in a longitudinal study (Branje et al., 2010) that the mother relationship quality predicted depressive symptomatology for boys and girls, but father relationship quality only predicted depressive symptoms for boys. In the same study was also pointed out that the relationship between girls and their mothers is usually of higher quality than the relationship with boys, and it’s also usually of higher quality than the relationship with their fathers, while boys doesn’t exhibit such difference in the relationship with their parents. In this way, the authors suggested that girls might be more affected by the relationship with their mothers, while boys also take into account the relationship quality with their fathers (Branje et al., 2010). Kenny, Dooley and Fitzgerald (2013) also found a tendency for girls to perceive higher levels of support in their relationships with their mothers compared to boys.

In addition to the impact on emotional regulation development, the relationship with parents might also exert an influence on the emotional regulation during adolescence and, in turn, on depressive symptomatology. In this regard, the association between the quality of the relationship with parents and the development of depression might also have an indirect effect over time associated with socioemotional factors of the adolescent, such as emotional regulation (Yap et al., 2007; Yap et al., 2014). This is also highlighted by Feng et al. (2009) when suggesting that parenting may have an impact on the development of psychopathology through at least two forms: a direct effect or through moderation of the relationship between emotional regulation and depressive symptomatology.

In this regard, according to Yap, Allen, and Sheeber (2007), interactions between adolescents and their parents that are characterized by low support and autonomy and high conflict are associated with poorer emotional regulation and higher levels of depressive symptomatology. In fact, a secure parent-child relationship enables children to feel supported and comfortable to express their emotions, which promotes the effectiveness of emotional regulation (Morris et al., 2017b). Also, the possibility for parents to coach their children to deal with negative emotional experiences allows children to regulate more effectively (Criss, Morris, Ponce-Garcia, Cui, & Silk, 2016).

The literature review previously presented is in line with a Transactional Model, where environmental factors (such as family relationships) interact with individual factors (like regulation style), influencing a more or less adaptive trajectory and the possible development of depressive symptomatology (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000; Ewing et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2009). Thus, the quality of the relationship with parents can interact with the adolescents’ ability to regulate their emotions, influencing the risk of developing depressive symptomatology (Feng et al., 2009).

Problem Statement

Despite the importance that the interaction between context and emotional regulation may have in the development of depressive symptomatology, there are still few studies addressing this interaction (Naragon-Gainey, McMahon, & Chacko, 2017), particularly the moderating effects of factors such as parental interactions on adolescents’ cognitive emotional regulation (Gilbert, 2012).

Research Questions

Taking into account the literature review previously presented, the present study intends to analyse the parental support moderating effects on the relation between cognitive emotional regulation strategies and depressive symptomatology in adolescence. We expect that parental support will moderate the relation between cognitive emotional regulation strategies and depressive symptomatology, thus meeting the Transactional Model and the literature review previously presented.

Purpose of the Study

With the present longitudinal study, we intend to contribute to a better knowledge of protective and risk factors in the development and maintenance of depressive symptomatology in adolescence, in order to enable a better and more effective treatment and prevention of depression.

Research Methods

Participants

The present longitudinal study analysed a community sample that is part of the research project “Prevention of Depression in Portuguese Adolescents: Study of the effectiveness of an intervention with adolescents and parents” (PTDC/MHC-PCL/4824/2012), funded by the Portuguese national funding agency for science, research and technology (FCT) and by Realan Foundation. The sample consisted of 566 Portuguese adolescents (60.25% female), with ages between 13 and 17 years old (M = 14.43; SD = .867). In terms of socioeconomic levels, adolescents are distributed at low (48.4%), medium (36.6%) and high (15%) levels. Regarding the marital status of parents, 437 adolescents reported having married parents (73.5%) or in a non-marital partnership (3.7%), 100 adolescents reported having divorced (12.9%) or separated (4.8%) parents, 15 teenagers reported having widowed parents (2.7%), and 14 adolescents reported having single parents (2.5%). There were no statistically significant gender differences in terms of age [t (429.398) = .404,

Procedure

This longitudinal study was authorized by the National Data Protection Commission (CNPD) and the General Directorate of Curriculum Innovation and Development (DGIDC). The sample was collected in public and private schools in the central region of Portugal through the completion of questionnaires in two evaluation moments, assessing in the first moment the cognitive emotional regulation strategies and the parental support, and in a second moment, six months later, the depressive symptomatology. Confidentiality was assured to all students who participated voluntarily. The informed consents of the students and their legal guardians were required.

Measures

Depressive symptomatology was assessed with the Children Depression Inventory – CDI (Kovacs, 1985; Kovacs, 1992; Portuguese version: Marujo, 1994). The CDI is a self-response questionnaire that allows the evaluation of depressive symptomatology in children and adolescents. A higher value on the total scale reveals a greater severity of the depressive symptomatology. Studies with the CDI Portuguese version revealed a unifactorial structure and Cronbach's alphas varying between .80 and .84 (Marujo, 1994; Dias & Gonçalves, 1999).

The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire – CERQ (Garnefski et al., 2001; translation and adaptation: Matos, Cherpe, & Serra, 2012) was used to assess cognitive emotional regulation strategies implemented by subjects when facing negative or traumatic life events. The CERQ is a multidimensional self-response questionnaire that can be administered to adolescents. The questionnaire is composed of nine distinct subscales of four items each, which translate into different emotional regulation cognitive strategies: self-blame; rumination; catastrophizing; blaming others; acceptance; positive reappraisal; refocus on planning; positive refocusing; putting into perspective (Garnefski et al., 2001). In the Portuguese psychometric qualities study (Serra, 2009), the internal consistency of each subscale was: .706 in self-blame; .685 in acceptance; .761 in rumination; .828 in positive refocusing; .791 in refocus on planning; .792 in positive reappraisal; .748 in putting into perspective; .770 in catastrophizing; and .738 in blaming others.

The Quality of Relationships Inventory – IQRI (Pierce, Sarason, & Sarason, 1991; Portuguese adolescents version: Marques, Matos, & Pinheiro, 2014; Marques, Pinheiro, Matos, & Marques, 2015) was used to assess mother support and father support perceived by adolescents. For the Portuguese versions, results revealed Cronbach's alpha coefficients of .85 in the mother support dimension (Marques et al., 2014) and .95 in the father support dimension (Marques et al., 2015).

Data Analysis

The statistical treatment of the data was done through the software IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0.0.2 for Windows.

An analysis of skewness (SK) and kurtosis (Ku) values revealed no significant biases with respect to the means, so the results’ normal distribution wasn’t compromised (Kline, 2016). In addition, the sample size of the present study (n = 566) allows for greater safety in resort to parametric tests.

In order to analyse the possible existence of gender differences in the variables of the present study, Student's t-tests were performed for independent samples, where it was considered statistically significant when

In order to study the moderating effect of parental support (IQRI) on the relation between cognitive emotional regulation strategies (CERQ) and depressive symptomatology (CDI) in adolescents, we performed the standardization of the moderator and independent variables, allowing a reduction of the multicollinearity effects (Jose, 2013). Preliminary analyses were also performed to ensure the adequacy of the data to Hierarchical Multiple Regression analysis (Pallant, 2011). The interaction terms were created by multiplying the predictor variable (CERQ factors) and the moderating variable (support factors - IQRI). Hierarchical Multiple Regression analyses were performed separately. The variables were sequentially introduced: gender was introduced in a first step in order to control the possible effects of this variable; in a second step the CERQ dimension being analysed; in a third step the IQRI dimension that was being considered as a moderating variable; and in a fourth step the interaction term between the CERQ dimension and the IQRI dimension. The total CDI score, obtained in the second evaluation time, was introduced as a criterion variable. It was considered to exist an interaction effect when the interaction term was found to be significant (

Findings

Descriptive analyses and gender differences

Girls presented higher levels of depressive symptomatology (CDI) (cf. Table

Regarding the cognitive emotional regulation strategies (CERQ), considering that a superior result in each factor is related to a greater use of the strategy, the results suggested that girls relied more on self-blame, rumination and acceptance compared to boys. Boys tended to blame others more than girls. However, in terms of the means differences magnitude, all variables with statistically significant gender differences had a small effect magnitude.

In terms of the parental support, there was only gender differences in the relationship with the mother. Girls tended to perceive higher levels of mother support compared to boys, but the effect magnitude was small.

Moderating effect of parental support on the relation between cognitive emotional regulation strategies and depressive symptomatology

The perception of father support didn’t reveal significant moderating effects. The perception of mother support only had a significant moderating effect (β = -.082,

When analysed separately, the perception of mother support (β = -.354,

These variables gave rise to statistically significant models in all four steps. The final model, in which the interaction between acceptance strategy and mother support was introduced, was statistically significant [R2 = .190, F(4, 557) = 32.744,

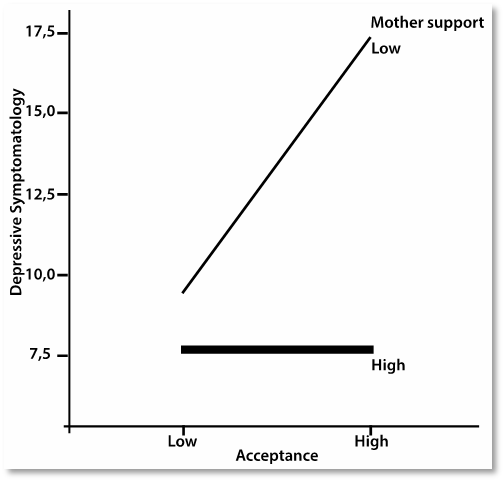

The graphic results (cf. Figure

Conclusion

Regarding the levels of depressive symptomatology in the present sample, girls presented significantly higher levels of symptomatology compared to boys. Although the magnitude of the means difference was small, these result is consistent with what has been verified in the literature (Cardoso, Rodrigues, & Vilar, 2004; Duarte et al., 2015; Erse et al., 2016; Ferreira, 2016; Gomes et al., 2015).

In terms of cognitive emotional regulation strategies, girls relied more on self-blame, rumination and acceptance compared to boys, while boys tend to resort more to blaming others, but the means difference magnitude was small. In fact, it is also pointed out in the literature a tendency for girls to resort more to internalized strategies, but there’s an inconsistency whether boys rely more or not on externalized strategies (Duarte et al., 2015; Ferreira, 2016; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2016).

Concerning the parental support perceived by adolescents, there wasn’t gender differences in terms of father support, but girls reported significantly higher levels of mother support, compared to boys, although the magnitude difference was small. Kenny et al. (2013) also found a tendency for girls to perceive higher levels of mother support compared to boys. It was also verified by Branje, Hale, Frijns, and Meeus (2010) that the relationship between girls and their mothers is usually of higher quality compared to boys.

After controlling gender effects, we observed a significant moderating effect of mother support (T1) on the relation between acceptance strategy (T1) and depressive symptomatology (T2).

Mother support was a negative predictor of depressive symptomatology, which is consistent with what has been found in the literature related to mother support (Branje et al., 2010; Duchesne & Ratelle, 2014; Sheeber et al., 2007) or parental support (Stice et al., 2004).

The cognitive emotional regulation strategy of acceptance was a positive predictor of depressive symptomology. Acceptance strategy is related to thoughts about the acceptance of the event, considering that there is nothing that can be done to change the situation and looking at the continuation of life beyond what happened (Garnefski et al., 2001). While acceptance strategy as measured by CERQ has been considered by some authors as a theoretically more adaptive strategy (d’Acremont & Van der Linden, 2007; Garnefski et al., 2001), other studies also found a positive relationship between acceptance and depressive symptomatology (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2016). One possible explanation for this result is that the items that make up the acceptance subscale of CERQ may reflect a degree of hopelessness (Martin & Dahlen, 2005), so adolescents may be confusing the acceptance strategy with a passive resignation to negative experiences or emotions, something that has also been mentioned in the literature (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006). This possible explanation supports what has been proposed by Rood, Roelofs, Bögels, and Arntz (2012), according to whom improvements in mood might occur more likely when the strategy is clearly explained and its proper use is encouraged.

In terms of the significant moderating effect obtained, the results suggested that when adolescents highly resort to acceptance in a maladaptive way, a higher perception of mother support may attenuate the impact of acceptance on depressive symptomatology, while a lower perception of mother support may lead to an increase in the depressive symptomatology levels. This means that mother support might protect from developing depressive symptomatology when adolescents highly misuse acceptance.

The moderating effect found in the present study is in consonance with a Transactional Model, showing how the interaction between the relationship with parents and the cognitive emotional regulation strategies used by adolescents can influence a more or less adaptive trajectory and the development of depressive symptomatology (Cummings et al., 2000; Ewing et al., 2015; Feng et al. 2009). In fact, the literature shows the importance of support and involvement by parents in the emotional regulation and depressive symptomatology in adolescence (Yap et al., 2007), revealing that the relationship with parents can interact with the adolescents’ ability to regulate their emotions, and thereby influence the risk to develop depression (Feng et al., 2009). In terms of this interaction, it’s important to notice that a secure parent-child relationship, which is also characterized by parental support, enables children to feel supported and comfortable to express their emotions (Morris et al., 2017b), creating a space for parents to help their children with emotional difficulties experienced by them, and also enabling an opportunity for parents to coach their children to deal with negative emotional experiences (Criss et al., 2016), which might give adolescents more adaptive strategies, but also protect them from the use of less adaptive strategies, like an acceptance misuse.

It should also be explored the fact that we didn’t found a moderating effect of father support. Two explanations might be considered: one is related to the parent’s gender and other to the adolescent’s gender. In terms of the parent’s gender, a moderating effect of support may only have arisen for the relationship with the mother because of a greater mother involvement in daily child-rearing activities, which might foster greater emotional closeness and, in turn, enables the mother to respond and prevent further episodes of negative emotional experiences (Duchesne & Ratelle, 2014; Duchesne, Ratelle, Poitras, & Drouin, 2009). Other explanation might be related to the adolescent’s gender, since it was verified by Branje et al. (2010) that both girls and boys might be affected by the quality of the relationship with their mothers, but boys also suffer from the impact of the relationship with their fathers, which was not observed in girls. In this way, if we had study the moderating effects separated for genders maybe we could have found a moderating effect of father support for boys.

Although the results found are relevant and in agreement with the literature, we should notice that it was only found a moderating effect of mother support in the relation between adolescent depressive symptomatology and one of nine cognitive emotional regulation strategies. Future studies should try to analyse possible variables that weren’t taken into account in the present study and that might have an impact on the parental support moderating effects, since the literature evidences an important role of positive relationship between parents and their children (Branje et al., 2010; Ewing et al., 2015; Kenny et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2008). An aspect that should be considered is that the present study sample obtained low levels of depressive symptomatology, which may have influenced the results found, whereby the use of a clinical sample could have accentuated the observed trends or even made possible the appearance of other significant moderating effects.

In terms of clinical implications, the present study provided a better understanding of protective and risk factors in the development of depression in adolescence, especially regarding the misuse of acceptance strategy and the way it is implemented according to the mother support perceived. This reveals a better knowledge about possible intervention targets in the treatment and prevention of depression, which is of extremely importance attending to the prevalence and prognosis of depressive symptomatology in adolescence (Cardoso et al., 2004; Costello, Copeland, & Angold, 2011; DGS, 2016; Erse et al., 2016; WHO, 2017).

Considering the results found, it’s pertinent to promote psychoeducation about cognitive emotional regulation strategies, explaining them and how to proper use each one (Rood, Roelofs, Bögels, & Arntz, 2012). This might be especially important in the case of acceptance strategy, which might have been misunderstood by the adolescents in the present study. It’s also important to give parents an opportunity to increase resilience, coping and parenting skills, and to increase their awareness of the influence of their parenting strategies, so that more resilient and skilled parents can help vulnerable adolescents to cope with their difficulties (Ewing et al., 2015; Pinheiro, Matos, Costa, Arnarson, & Craighead, 2015), not only by promoting a safer place for adolescents to express their difficulties (Morris et al., 2017b), but also by coaching their children to better deal with negative emotional experiences (Criss et al., 2016).

The present study presents some limitations, such as the exclusive use of a community sample, not allowing the generalization of the results for clinical samples. Furthermore, the data collection procedure relied only on self-answering questionnaires and didn’t controlled variables like social desirability, humour at the time of collection or low motivation and adherence to participate in the present study.

The results obtained regarding the acceptance strategy suggest that might be important to review this CERQ subscale (Garnefski et al., 2001) in the Portuguese version, and also to study the use of a passive resignation strategy towards negative emotional experiences by Portuguese adolescents.

In future studies, it might be useful to compare adolescents’ trajectories with and without depressive symptomatology, and also to analyse the contribution of sociodemographic variables, such as socioeconomic status and the marital status of parents, and parental psychopathology. It would be equally interesting to see if the symptoms experienced are associated with future changes in the quality of the relationship perceived by adolescents, considering that in the study by Stice, Ragan, and Randall (2004) there was no decrease in support perception.

In conclusion, the present study contributed to the advance of knowledge about the effects of the interaction between parental support and emotional regulation. It’s relevant to deepen the study of the moderating effects of parental support on the relation between cognitive emotional regulation and depressive symptomatology in adolescence, looking for a better intervention and prevention of depression, and contributing to a better mental health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the adolescents who participated in the present study and to FCT and Realan Foundation that funded the study.

References

- Allen, J. P., Porter, M., McFarland, C., McElhaney, K. B., & Marsh, P. (2007). The Relation of Attachment Security to Adolescents’ Parental and Peer Relationships, Depression, and Externalizing Behavior. Child Development, 78(4), 1222-1239. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01062.x

- Armsden, G. C., McCauley, E., Greenberg, M. T., Burke, P. M., & Mitchell, J. R. (1990). Parent and Peer Attachment in Early Adolescent Depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18(6), 683-697. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01342754

- Berking, M., & Wupperman, P. (2012). Emotion regulation and mental health: recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. Current opinion in psychiatry, 25(2), 128-134. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503669

- Betts, J., Gullone, E., & Allen, J. S. (2009). An examination of emotion regulation, temperament, and parenting style as potential predictors of adolescent depression risk status: A correlational study. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 473-485. https://dx.doi.org/10.1348/026151008X314900

- Branje, S. J. T., Hale, W. W., Frijns, T., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2010). Longitudinal Associations Between Perceived Parent-Child Relationship Quality and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 38(6), 751-763. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9401-6

- Cairns, K. E., Yap, M. B. H., Pilkington, P. D., & Jorm, A. F. (2014). Risk and protective factors for depression that adolescents can modify: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 169, 61-75. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.006

- Cardoso, P., Rodrigues, C., & Vilar, A. (2004). Prevalência de sintomas depressivos em adolescentes portugueses. Análise Psicológica, 22(4), 667-675. https://dx.doi.org/10.14417/ap.264

- Costello, E. J., Copeland, W., & Angold, A. (2011). Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: What changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(10), 1015-1025. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.14697610.2011.02446.x

- Criss, M. M., Morris, A. S., Ponce-Garcia, E., Cui, L., & Silk, J. S. (2016). Pathways to adaptive emotion regulation among adolescents from low-income families. Family Relations, 65(3), 517–529. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/fare.12202

- Cummings, E. M., Davies, P. T., & Campbell, S. B. (2000). Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford Press.

- d’Acremont, M., & Van der Linden, M. (2007). How is impulsivity related to depression in adolescence? Evidence from a French validation of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Journal of Adolescence, 30(2), 271–282. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.02.007

- Dias, P., & Gonçalves, M. (1999). Avaliação da ansiedade e da depressão em crianças e adolescentes (STAIC-C2, CMAS-R, FSSC-R e CDI): Estudo normativo para a população portuguesa. In A. P. Soares, S. Araújo, & S. Caires (Eds.), Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos (pp. 553-564). Braga: APPORT.

- Direção-Geral da Saúde (DGS) (2016). Portugal: Saúde Mental em Números – 2015: Programa Nacional para a Saúde Mental. Lisboa: Direção-Geral da Saúde.

- Duarte, A. C., Matos, A. P., & Marques, C. (2015). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: gender’s moderating effect. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 165, 275-283. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.632

- Duchesne, S., & Ratelle, C. F. (2014). Attachment Security to Mothers and Fathers and the Developmental Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence: Which Parent for Which Trajectory? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(4), 641-654. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0029-z

- Duchesne, S., Ratelle, C. F., Poitras, S. C., & Drouin, É. (2009). Early adolescent attachment to parents, emotional functioning and worries about the middle school transition. Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(5), 743–766. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431608325502

- Erse, M. P. Q. A., Simões, R. M. P., Façanha, J. D. N., Marques, L. A. F. A. M., Loureiro, C. R. E. C., Matos, M. E. T. S., & Santos, J. C. P. (2016). Adolescent depression in schools: + Contigo Project. Revista de Enfermagem Referência, 4(9), 37-44. https://dx.doi.org/10.12707/RIV15026

- Ewing, E. S. K., Diamond, G., & Levy, S. (2015). Attachment-based family therapy for depressed and suicidal adolescents: theory, clinical model and empirical support. Attachment & Human Development, 17(2), 136-156. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2015.1006384

- Feng, X., Keenan, K., Hipwell, A. E., Henneberger, A. K., Rischall, M. S., Butch, J., Coyne, C., Boeldt, D., Hinze, A. K., & Babinski, D. E. (2009). Longitudinal Associations Between Emotion Regulation and Depression in Preadolescent Girls: Moderation by the Caregiving Environment. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 798-808. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014617

- Ferreira, N. A. (2016). Emotion regulation as a predictor of depression and psychosocial impairment in adolescence moderated by negative life events. Masters’ dissertation presented to Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Coimbra, Portugal.

- Garnefski, N., Boon, S., & Kraaij, V. (2003). Relationships Between Cognitive Strategies of Adolescents and Depressive Symptomatology Across Different Types of Life Event. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(6), 401–408. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1025994200559

- Garnefski, N., Hossain, S., & Kraaij, V. (2017). Relationships between maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology in adolescents from Bangladesh. Archives of Depression and Anxiety, 3(2), 23-29. https://dx.doi.org/10.17352/2455-5460.000019

- Garnefski, N., & Kraaij, V. (2006). Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(8), 1659–1669. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.009

- Garnefski, N., & Kraaij, V. (2014). Bully victimization and emotional problems in adolescents: Moderation by specific cognitive coping strategies? Journal of Adolescence, 37(7), 1153-1160. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.07.005

- Garnefski, N., & Kraaij, V. (2016). Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Cognition and Emotion, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1232698

- Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(8), 1311-1327. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6

- Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & van Etten, M. (2005). Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Adolescence, 28(5), 619-631. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.009

- Garnefski, N., Legerstee, J., Kraaij, V., Van Den Kommer, T., & Teerds, J. (2002). Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a comparison between adolescents and adults. Journal of Adolescence, 28(5), 603-611. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.009

- Gilbert, K. E. (2012). The neglected role of positive emotion in adolescent psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 467-481. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.005

- Gomes, A. S., Matos, A. P., Monteiro, S., Mónico, L. (2015). Maltreatment Experiences and Depression in Adolescents: The Moderating Effect of Psychosocial Functioning. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 53-66. https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2015.08.6

- Hilt, L. M., Armstrong, J. M., & Essex, M. J. (2012). Early family context and development of adolescent ruminative style: Moderation by temperament. Cognition & Emotion, 26(5), 916-926. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.621932

- Hyde, J. S., Mezulis, A. H., & Abramson, L. Y. (2008). The ABCs of Depression: Integrating Affective, Biological, and Cognitive Models to Explain the Emergence of the Gender Difference in Depression. Psychological Review, 115(2), 291-313. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033295X.115.2.291

- Jose, P. E. (2013). Doing statistical mediation and moderation. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Kenny, R., Dooley, B., & Fitzgerald, A. (2013). Interpersonal relationships and emotional distress in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 36(2), 351-360. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.005

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (4th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Kovacs, M. (1985). The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 21(4), 995-998. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp419

- Kovacs, M. (1992) The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems.

- Kraaij, V., & Garnefski, N. (2012). Coping and depressive symptoms in adolescents with a chronic medical condition: A search for intervention targets. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1593–1600. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.06.007

- Kraaij, V., Garnefski, N., de Wilde, E. J., Dijkstra, A., Gebhardt, W., Maes, S., & Ter Doest, L. (2003) Negative Life Events and Depressive Symptoms in Late Adolescence: Bonding and Cognitive Coping as Vulnerability Factors? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(3), 185–193. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1022543419747

- Larsen, J. K., Vermulst, A. A., Geenen, R., Middendorp, H., English, T., Gross, J. J., Ha, T., Evers, C. & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2013). Emotion Regulation in Adolescence: A Prospective Study of Expressive Suppression and Depressive Symptoms. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(2), 184-200. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431611432712

- Marôco, J. (2010). Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, Software e Aplicações. Pêro Pinheiro: ReportNumber.

- Marques, D., Matos, A. P., & Pinheiro, M. R. (2014). Estudo da estrutura fatorial da versão mãe do IQRI para adolescentes. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 15(1), 234-244. https://dx.doi.org/10.15309/14psd150119

- Marques, D., Pinheiro, M. R., Matos, A. P., & Marques, C. (2015). Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the QRI Father’s Version in a Portuguese sample of adolescents. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 165, 267-274. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.631

- Martin, R. C., & Dahlen, E. R. (2005). Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(7), 1249-1260. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.004

- Marujo, H. (1994). Síndromas depressivos na infância e na adolescência. Doctoral dissertation presented to Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Lisbon, Portugal.

- Matos, A. P., Cherpe, S., & Serra, A. R. (2012). Psychometric study of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) in Portuguese adolescents [unpublished manuscript].

- Morris, A. S., Criss, M. M., Silk, J. S., & Houltberg, B. J. (2017a). The Impact of Parenting on Emotion Regulation During Childhood and Adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 233-238. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12238

- Morris, A. S., Houltberg, B. J., Criss, M. M., & Bosler, C. (2017b). Family context and psychopathology: The mediating role of children’s emotion regulation. In L. Centifanti & D. Williams (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of developmental psychopathology (pp. 365–389). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The Role of the Family Context in the Development of Emotion Regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361-388. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

- Naragon-Gainey, K., McMahon, T. P., & Chacko, T. P. (2017). The Structure of Common Emotion Regulation Strategies: A Meta-Analytic Examination. Psychological Bulletin, 143(4), 384-427. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000093

- Öngen, D. E. (2010). Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression and submissive behavior: Gender and grade level differences in Turkish adolescents. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1516-1523. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.358

- Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS (4th ed.). Australia: Allen & Unwin.

- Pierce, G., Sarason, I., & Sarason, B. (1991). General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: Are two constructs better than one? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(6), 1028-1039. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.6.1028.

- Pinheiro, M. R., Matos, A. P., Costa, J. J., Arnarson, E. O., & Craighead, W. E. (2015). A parental program for the prevention of depression in adolescents. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, 6, 95-108. https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2015.07.9

- Rawatlal, N., Kliewer, W., & Pillay, B. J. (2015). Adolescent attachment, family functioning and depressive symptoms. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 21(3), 80-85. https://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJP.8252

- Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bögels, S. M., & Arntz, A. (2012). The Effects of Experimentally Induced Rumination, Positive Reappraisal, Acceptance, and Distancing When Thinking About a Stressful Event on Affect States in Adolescents. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 40(1), 73-84. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9544-0

- Serra, A. R. G. (2009). Regulação Emocional e Estilos Parentais: Factores de risco (ou de protecção) no desenvolvimento da Perturbação Depressiva Major nos Adolescentes. Masters’ dissertation presented to Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Coimbra, Portugal

- Sheeber, L. B., Davis, B., Leve, C., Hops, H., & Tildesley, E. (2007). Adolescents’ Relationships With Their Mothers and Fathers: Associations With Depressive Disorder and Subdiagnostic Symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 144-154. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144

- Southam-Gerow, M. A. (2013). Emotion Regulation in Children and Adolescents: A Practitioner’ Guide. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 69-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005

- Stice, E., Ragan, J., & Randall, P. (2004). Prospective Relations Between Social Support and Depression: Differential Direction of Effects for Parent and Peer Support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(1), 155-159. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155

- Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the society for research in child development, 59(2‐3), 25-52. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01276.x

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2017). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254610/1/WHO-MSDMER2017.2eng.pdf?utm_source=WHO+List&utm_campaign=d538ec500cEMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2016_12_14&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_823e9e35c1d538ec500c&utm_source=WHO+List&utm_campaign=d538ec500cEMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2016_12_14&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_823e9e35c1-d538ec500c260570285

- Yap, M. B. H., Allen, N. B., & Sheeber, L. (2007). Using an Emotion Regulation Framework to Understand the Role of Temperament and Family Processes in Risk for Adolescent Depressive Disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology, 10(2), 180-196. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10567-006-0014-0

- Yap, M. B. H., Pilkington, P. D., Ryan, S. M., & Jorm, A. F. (2014). Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 156, 8-23. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.007

- Zhou, Q., Sandler, I. N., Millsap, R. E., & Wolchik, S. A. (2008). Mother-Child Relationship Quality and Effective Discipline as Mediators of the 6-Year Effects of the New Beginnings Program for Children From Divorced Families. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 579-594. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.579

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 February 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-055-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

56

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-719

Subjects

Pedagogy, education, psychology, linguistics, social sciences

Cite this article as:

Antunes, J., Matos, A. P., & Costa, J. J. (2019). Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: Longitudinal Effects Of Emotional Regulation Moderated By Parental Support. In S. Ivanova, & I. Elkina (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2018, vol 56. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 380-394). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.02.02.42