Abstract

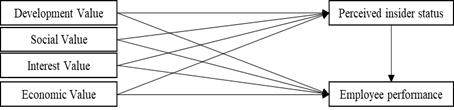

Based largely on talent shortages, the war on talent has given place to the war for talent. Organizations, as a result, have begun to seek and develop strategies to cope with difficulties in attracting and retaining a talented workforce. In this study, the concept and role of employer branding, as one of these strategies, has been studied extensively and the role of employer brand practices on the perceived insider status and employee performance has been investigated from the perspectives of current employees. Also, it has been assessed to what extent perceived insider status has an impact on the employer performance. In the light of data collected from 175 respondents from different sectors, results of the study have revealed that social, development and interest value aspects of employer brand influence the perceived insider status and performance of employees. Additionally, perceived insider status has a positive impact on employee performance. Besides, it has been observed that economic value aspect of employer brand has no impact on the employee performance and perceived insider status.

Keywords: Employer brandemployer brand attractivenessperceived insider statusemployee performance

Introduction

In the age of knowledge economy, more and more organizations have begun to experience difficulties in achieving sustainability and competitive advantage due to increased competition. One of these challenges is the difficulty in finding skilled workforce due to the aging of the population and retirement of larger generations, emergence of new business lines and open market through globalization (Wahba & Elmanadily, 2015).

Based on their research conducted in 77 US companies via a survey from 6,000 executives and 20 companies’ case studies, Chambers et al. (1998) accentuated that organizations have experienced to “war for talent” because of difficulty in attracting and retaining the workforce stemming from talent shortages. In a similar vein, Dobbs et al. (2012) carried out a research in 70 countries and stated that advanced economies could experience talent shortage by 16 million to 18 million college-educated workforces while there could be potential surplus nearly from 90 million to 95 million low-skill workers’ in 2020. These talent shortages have compelled organizations to review their attraction and retention strategies for gaining a sustainable competitive advantage in the highly competitive business environment. As a result of this talent scarcity and war for talents, the aim of attracting and retaining the best employees have led to the emergence of the notion of employer brand in organizations. Accordingly, Chambers et al. (1998) proposed that creating great employee value proposition is the best way of winning the war for talent thanks to retaining and attracting the best talents in the organization.

As a result, growing stream of research has put emphasize on employer brand concept for the attractiveness of organizations as an employer (Ambler & Barrow, 1996; Berthon, Ewing, & Hah, 2005; Lievens & Highhouse, 2003). With this regard, a vast number of studies have given ample attention to the attraction of potential employees’ aspect of employer brand. When the studies are examined, it is seen that employer brand attributes as having good working condition and competence attributes (Van Hoye, Bas, Cromheecke, & Lievens, 2013), innovativeness and competence attributes (Lievens & Highhouse, 2003), work content and work culture (Rampl, 2014), symbolic attributes (Lievens, 2007), social and reputation value (Schlager, Bodderas, Maas, & Luc Cachelin 2011); working environment, development, economic value and image (Gungordu, Ekmekcioglu, & Simsek, 2014); responsibility and empowerment and compensation and location (Agrawal & Swaroop, 2009); psychological value (Sivertzen, Nilsen, & Olafsen, 2013); organizational culture, brand name and compensation (Leekha Chhabra & Sharma, 2014) have made important contributions to the employer brand attractiveness in the perspective of prospective employees.

Within this framework, our research responds to a call to investigate the employer brand concept in terms of current employees’ view and their organizational outcomes (Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004; Maxwell & Knox, 2009). In this context, this study intends to contribute to the literature with being one of the first studies delineating the impact of employer brand on the employee performance and perceived insider status of current employees.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Employer Brand

The first serious discussions and analyses of employer brand emerged during the 1990s with the study of Ambler and Barrow (1996) via accentuating the employer role and characteristics of organizations. They defined employer brand as “the package of functional, economic and psychological benefits provided by employment, and identified with the employing company” (Ambler and Barrow, 1996 p. 188). Employer brand, based on this definition, provides benefits to employees with offering “(1) developmental and/or useful activities (functional); (2) material or monetary rewards (economic); and (3) feelings such as belonging, direction and purpose (psychological)” (Ambler and Barrow, 1996 p.189).

Defining employer brand as “a strategy of internal and external communication of the unique attributes that establishes the identity of the firm as an employer and what differentiates it from others, with the aim of attracting and retaining potential and current employees”, Wahba and Elmanadily (2015 p. 149) has exerted more comprehensive view of employer brand with stating groups targeted through employer brand. In the light of above points, it can be posited that employer brand, given in terms of target market, focus on two aspects as external and internal employer brand (Lievens and Slaughter, 2016). External employer brand refers to the perception of outsiders about the attributes of organizations as an employer while internal employer brand refers to the perception of insiders about employer attributes of the organization.

In this context, positive employer brand associations that will shape these perceptions of both prospective and current employees have been decisive for the employer brand attractiveness (Collins & Kanar, 2014). Edwards (2009) demonstrated that good reputation and organizational identity have an effect on attracting prospective and current employees.

Employee value proposition, which is another important concept for creating a positive perception of target employees, is discussed as “the unique and differentiating promise a business makes to its employees and potential candidates” (Sullivan, 2002, p. 20). With a similar way in the marketing concept focusing on the value creation for the customers, employer brand aims to create unique employee value proposition for the potential and current labor market. With this regard, the ideal employee value proposition should diagnose the organizational culture and provide differentiated and unique emotional and functional benefits (Bas, 2011). In a nutshell, creating strong employer value proposition contribute to the development of positive associations and eventually attractiveness of employer brand.

As posited by Berthon, Ewing and Hah, employer brand attractiveness refers to “the envisioned benefits that a potential employee sees in working for a specific organization” (2005 p.156) and determines attractiveness according to the existence of five dimensions.

Interest value assesses the extent to which employers provide an exciting organizational environment and benefit from the creativity of employees for producing high quality and innovative products.

Social value refers to the existence of a good relationship with colleagues as well as supervisors and happy working environment.

Economic value includes the existence of remuneration and promotion opportunities, above-average wages, good retirement policies.

Development value articulates the training opportunities, gaining career-enhancing work experience, recognition, and appreciation from the organization.

Application value refers to the extent to which organizations provide a facility to employees for applying and using their knowledge and teach this knowledge to other members of the organization.

In this vein, having a strong employer brand provides a vast number of benefits for organizations through contributing in the development of such favorable employees’ attitudes as employee retention (Barrow & Mosley, 2011; Knox & Freeman, 2006), work engagement (Piyachat, Chanongkorn, & Panisa, 2014), satisfaction (Heger, 2007; Davies, 2008), organizational identification (Lievens, Van Hoye & Anseel, 2007; Schlager et al., 2011), employee commitment (Ito, Brotheridge, & McFarland, 2013).

In a nutshell, employer brand concept has gained an importance for the organizational success and competitive advantage thanks to its role in attracting and retaining the best possible employees. In order to overcome the war for talent, organizations should formalize their existing activities in harmony with the expectation of both prospective and current employees (Berthon, Ewing and Hah, 2005).

Hypotheses Development

Employer Brand and Perceived Insider Status

Employee-organization relationship has drawn attention from organization scholars in recent decades. Defined as “the extent to which an individual employee perceives him or herself as an insider within a particular organization” (Stamper & Masterson, 2002), perceived insider status has embraced this employment relationship in the sense of being a central part of organization and feeling of that they are insiders.

Perceived insider status of employees has mostly embraced with regard to benefits provided by the organizations (Ding & Shen, 2017) and fulfillment of their needs. These needs can be classified as economic needs (payment and promotions), relatedness needs (interaction and communication among supervisors and co-workers, participation in decision making) and developmental needs (career and growth opportunities, training programs). As a result of these benefits, employees tend to promote the perception of being a member as well as a part of an organization (Masterson & Stamper, 2003). Besides, monetary inducements and nonmonetary inducements (social atmosphere, rewards, work-life balance, perceived organizational support, training) contribute to the feeling of being a central part of the organization (March & Simon, 1958).

In a similar vein, benefits provided by the organizations, as an employer, contribute to the formation of insider status of employees. According to Dai and Chen (2015) inducements provided by the organizations can be classified as economic inducements, inducements of development through training and advancement opportunities and social-emotional support through strong interaction with supervisors and colleagues. These rewards and inducements, based on the social exchange theory (Blau,1964), shape the perception of employees through showing the importance given to employees by the organization and prompt employees to the obligation of working better. Besides, employees tend to perceive themselves as an insider.

Shore et al. (2011) executed that three factors can be a predictor of inclusion of employees given as organizational climate considering the fairness and diversity; leadership behavior leading inclusiveness of employees to activities and decision making of the organization, and organizational activities promoting the satisfaction of uniqueness and belongingness needs through the fulfillment of needs of employees. Previous research has stated that providing training and promotions opportunity and quality of the supervisor-subordinate relationship can enhance the perceived insider status (Wang, Feng, Prevellie & Wu, 2017). Similarly, Hui, Lee, and Wang (2015) revealed that perceived supervisor support affects the perception of owning insider status. Additionally, a strong relationship with the colleagues, as well as recognition from management, arouse a feeling of being insider thanks to a supportive and friendly working environment (Shore, Cleveland & Sanchez, 2017).

In the light of these arguments, it is proposed that the organizations’ practices through social, economic, development, application and interest value aspects of employer brand have made important contributions to the improvement of insider status. In this context, we propose in this current study that:

H1: Social value is positively related to perceived insider status.

H2: Economic value is positively related to perceived insider status.

H3: Development value is positively related to perceived insider status.

H4: Interest value is positively related to perceived insider status.

These arguments suggest that employees may be motivated to perceive themselves as members of the organization to the extent that the organization can fulfill a variety of important employee needs, such as economic needs (e.g., pay and benefits), relatedness needs (e.g., co-workers with similar backgrounds and values, social status), or developmental needs (e.g., challenge and growth opportunities).These correspond closely with the rights that organizations may grant to employees, particularly social rights (economic benefits, social status, and training opportunities; Graham, 1991). Simultaneously, employees should be more likely to perceive themselves as organizational members to the extent that they make contributions toward organizational goals and objectives and other members’ needs. In contrast to organizational the commitment that describes an individual's affective attachment to an organization as a whole, perceived insider status relates to an individual's perceived importance or identity defined in terms of relative standings in an organization. In contrast to organizational the commitment that describes an individual's affective attachment to an organization as a whole, perceived insider status relates to an individual's perceived importance or identity defined in terms of relative standings in an organization. In contrast to organizational the commitment that describes an individual's affective attachment to an organization as a whole, perceived insider status relates to an individual's perceived importance or identity defined in terms of relative standings in an organization. In contrast to organizational the commitment that describes an individual's affective attachment to an organization as a whole, perceived insider status relates to an individual's perceived importance or identity defined in terms of relative standings in an organization.

Employer Brand and Employee Performance

Organizations operating in today’s business environment characterized by high competition increasingly have made an effort to differentiate themselves from other organizations. With this regard, the literature has garnered much empirical evidence demonstrating that investing in the human resources, on the basis of resource-based view, is vital for gaining competitive advantage for organizations (Barney, 1991). In this context, developing employees’ knowledge, competencies and abilities formalize their tendency of contributing organizational success as well as increasing their motivation and performance (Bowen & Ostroff, 2004; Fey, Björkman, & Pavlovskaya, 2000).

According to the findings of the previous research employer branding activities have an impact on financial and non-financial firm performance (Biswas & Suar, 2016). Fulmer, Gerhart and Scott (2003) investigated the impact of “great place to work” perception on the performance of the 100 best companies to work for in the US. Results showed that positive relationship via participation and collaboration leads to an increase in motivation of employees as well as firm performance.

In terms of the employees’ performance, Katua (2015) revealed that training and development contribute to the improvement of knowledge, skills, and abilities of banking employees and leads to enhance the performance of employees as well as increase the quality and lower the cost because of errors. With this regard, training and development are likely to have a positive impact on performance to the extent to which the firm increases employees’ satisfaction (Fey & Björkman, 2001). Besides, providing related and necessary knowledge for vocational development and determining career-related goals for employees help to improve their skills leading better performance (Amin et al., 2014).

On the other hand, Mayson and Barret (2006) proved that high performance and growth have been actualized through the agency of compensation packages. In this vein, reward programs including financial rewards, pay and benefits, promotions and incentives lead employees to increase their performance. Furthermore, recognizing the employees indicates the awareness and appreciation of organizations to employees and contributes their performance (Danish & Usman, 2010). Pao-Long and Wei-Ling (2002) are of the view that performance-based incentives and promotion opportunities, as well as benefits as retirement and profit sharing plans, enhance the employees’ performance. Additionally, Heger (2007) showed that financial rewards based on pay performance, rather than base pay, within the scope of the employer value proposition are one of the key components of employees’ productivity. In a similar vein, effective communication and interaction with both supervisors and subordinates increase the employees’ performance via organizational support perception by providing necessary information and clarifying organizational goals (Neves & Eisenberger, 2012).

Drawing on the above discussion, creating an attractive workplace through employer brand may contribute to the performance of employees thanks to positive employee relations and attitudes. Based on the reviewed literature, the following hypotheses are suggested:

H5: Social value is positively related to employee performance.

H6: Economic value is positively related to employee performance.

H7: Development value is positively related to employee performance.

H8: Interest value is positively related to employee performance.

Perceived Insider Status and Employee Performance

Based on the ground of Inducements and Contributions Theory (March & Simon, 1958),

Chen and Tang (2018) revealed that perceived inclusion of employees enhance the employees’ innovator and team member role performance while this insider status does not affect job role performance, career role performance, and organization member role performance. Mirap (2008) examined the relationship between perceived insider status and performance and executed that perceived insider status, in turn, leads to task performance, contextual performance, and total performance. According to the study of Pearce and Randel (2004), which deals with insider status on the basis of the feeling of socially included in the workplace, the sense of inclusion affects employee performance. Taken together, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H9: Perceived insider status is positively related to employee performance.

Research Method

Sample and Data Collection

The survey was carried out in Turkey and through applying the convenient sampling technique, 175 questionnaires were gathered from respondents working in various organizations. Respondents were instructed to evaluate their organizations, as an employer, in terms of opportunities they provide as well as their insider status and their performance.

In terms of sample profile, 42,9% of the participants are women and 57,1% of the participants are men. 44% of all participants have university graduate, and 43,3% of all participants have a master degree and 12,7% of all participants have a doctoral degree. 32,7% of the sample is in the age group of 22-29, 44,2% of the sample is in the age group of 30–37, 17% of the sample is in the age group of 38-45, and 6,1% of the sample is in the age group of 46 and above ages. In terms of job tenure, 3,5% of the employees have been working for less than 1 year, 31% of them have been working for 1-5 years, 33,9% of them have been working for 6-10 years, 31,6% of them have been working for 11 and above years. For the sectoral distribution 34,4% of respondents work in the education sector, 17,5% of them work in service sector, 12,5% in manufacturing sector, 10% in banking and finance sector, 8,8% in automotive sector, 3% in information sector and 13,8% in another sector like building, textile, defence, and chemical industry respectively.

Measures

The questionnaire was used for data collection method and consists of two parts. Questions about the demographic variables of the participants are included in the first part of the questionnaire. In the second part of the questionnaire, questions related employer brand, perceived insider status, and employee performance were included. A five-point Likert Type Rating scale ranged from ‘strongly agree’ (5) to ‘strongly disagree’ (1) was used throughout the measurement instruments.

Employer brand.

Employer brand was measured with a 25-item scale of Berthon, Ewing and Hah (2005) to determine the perceived attractiveness level of employer brand attributes from the view of current employees. On the original scale, employer brand has been measured with dimensions of economic, development, social, interest and application value and each dimension consists of 5 questions and all dimensions were found to be above the acceptable Cronbach α of, 70.

Perceived Insider Status.

Perceived Insider Status was measured with a scale developed by Stamper and Masterson (2002). The scale has been measured with six items such as " I feel very much a part of my work organization", " My work organization makes me believe that I am included in it ". The scale has a reported alpha reliability of ,88.

Employee performance.

4 items measuring employee performance were adopted from the scale used in the study of Kirkman and Rosen (1999) and Sigler and Pearson (2000). Sample items include “I complete my tasks on time” and “I meet or exceed my goals” The scale has a reported alpha reliability of ,94.

Analyses and Results

In order to test construct validity of the research model, variables were tested with factor analysis using principal component analysis with varimax rotation method for determining the factors structure of dependent and independent variables and the results are presented in Table

The Bartlett's Test of Sphericity Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistics was used for determining the sampling adequacy for the analysis and it is expected that KMO statistics value should be greater than ,60 (Kaiser & Rice, 1974). Finally, KMO test was found to be ,915 for employer brand; ,871 for perceived insider status and ,797 for the employee performance. Besides, The Bartlett's Test of Sphericity is significant (χ2 = 2624,388, p < 0.001 for employer brand; χ2 = 946,222, p < 0.001 for perceived insider status; χ2 = 211,466, p < 0.001 for the employee performance).

As a result of analyses, three items were left out from the analysis because of low factor loadings. Finally, 22 items with four factors have emerged for the employer brand as development value explaining 23,05% of the variance, social value explaining 19,25% of the variance, interest value explaining 15,18% of the variance and social value explaining 9,56% of the variance.

On the other hand, the one-dimensional structure was found for Perceived insider status and employee performance. 6 items explained 80,99% of total variance and employee performance explained 72,78% of total variance with four items.

In terms of the Cronbach's Alpha values ,60 which was stated as the lowest acceptable level in literature were used for determining the reliability of the scales (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Cronbach's Alpha coefficients of all dimensions remained above the acceptance values with a minimum α = ,856, indicating that all dimensions had internal consistency.

Pearson correlations were computed to determine relationships between four dimensions of employer brand and perceived insider status and employee performance (see Table

According to the results, it was found that economic value, interest value, development value, and social value have a positive relationship with the perceived insider status and employee performance. Highest correlations were between development value and perceived insider status (r=,778; p <0,001). Besides, interest value has the highest correlation with employee performance (r=,650; p <0,001).

After the correlation analysis, the relationship between employer brand, employee performance, and perceived insider status was tested through multiple regression analysis. Results of the analyses have been shown in Table

Results of regression analysis conducted for testing the relationship between employer brand and perceived insider status showed that there is a significant effect of interest value (β= ,156; p=,030), development value (β= ,578; p=,000) and social value (β= ,152; p=,021) on the perceived insider status. Therefore, H1, H2 and H3 are supported. On the other hand, economic value has no significant effect on the perceived insider status, not supporting H4.

On the other hand, there is a significant effect of interest value (β= ,367; p=,000), development value (β= ,180; p=,039) and social value (β= ,321; p=,000) on the employee performance. Therefore, H5, H6 and H7 are supported. On the contrary, economic value has no significant influence on employee performance, not supporting H8.

Finally, perceived insider status was significantly related to employee performance (β= ,565; p=,000), supporting H9.

Conclusion and Discussions

This study has shed some light on the relationship between employer brand by virtue of social, economic, development and interest value, employee performance and perceived insider status to fill the gap in the literature thanks to being one of the first studies examining employee performance and perceived insider status in terms of employer brand.

Findings of the study show that social value, interest value, and development value have a positive impact on the perceived insider status of the employees. The results of this study comport with the study of Wang et al. (2017) who noted that training opportunities and strong supervisor-subordinate relationship lead employees to perceive themselves as an insider.

In addition, social value, interest value, and development value have a positive impact on the employee performance, which is in line with the finding of Katua (2015) and Fey and Björkman (2001) accentuating the importance of development and training for enhancing employee performance. In agreement with research of Danish and Usman (2010), appreciation and recognition through development value also are the predictor of the performance of employees. In terms of social value, along with similar lines with Neves and Eisenberger (2012), social interaction and quality of the relationship between colleagues and managers play important role in yielding employee performance.

An interesting finding of this study is that providing payment and financial rewards through economic value aspect of the employer brand does not influence the employee performance contrary to past studies (Heger, 2007; Mayson & Barret, 2006; Pao-Long & Wei-Ling, 2002) which showed that financial programs, payment and benefits and incentives increase the performance of employees. Additionally, economic value also does not affect the perceived insider status.

The underlying reason for these findings may be based on the idea that the symbolic framework of employer brand rather than monetary benefits, job security, and task demand is a better predictor of the employer brand attractiveness (Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004; Lievens, 2007; Lievens & Highhouse, 2003). Piyachat, Chanongkorn and Panisa (2014) also emphasized the necessity for organizations to focus on emotional rather than the economic factors of employer brand.

In a nutshell, this study shows that organizations should concentrate on creating value for the employees through employer brand based on the development opportunities, strong social relationship, novel work practices and getting benefits from the creativity of the current employees rather than an economic aspect of employer brand for the higher perceived insider status and employee performance.

The generalizability of these results is subject to certain limitations. Firstly, the study was conducted in Turkey. For generalizability, it is recommended that the current research model should be tested in different cultural context. Besides, in terms of performance, the only perceptual performance of employees has been investigated in the current research. In future investigations, it might be valuable to examine the role of employer brand on the different aspects of performance such as contextual and task performance. Additionally, increasing the sample size would be crucial for the generalizability of the results. The current study, also, only has focused on the consequences of the employer brand. A further study could assess the antecedents of the employer brand from the point of organizational culture, leadership types and organizational climate. Besides, future research can investigate the role of participating the decision making and delegation in the relationship between employer brand, employee performance, and perceived insider status.

References

- Agrawal, R. K., & Swaroop, P. (2009). Effect of employer brand image on application intentions of B-school undergraduates. Vision, 13(3), 41-49.

- Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of brand management, 4(3), 185-206.

- Amin, M., Khairuzzaman Wan Ismail, W., Zaleha Abdul Rasid, S., & Daverson Andrew Selemani, R. (2014). The impact of human resource management practices on performance: Evidence from a Public University. The TQM Journal, 26(2), 125-142.

- Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career development international, 9(5), 501-517.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal Of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Barrow, S., & Mosley, R. (2011). The employer brand: Bringing the best of brand management to people at work. John Wiley & Sons.

- Berthon, P., Ewing, M., & Hah, L. L. (2005). Captivating company: dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. International journal of advertising,24(2), 151-172.

- Biswas, M. K., & Suar, D. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of employer branding. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(1), 57-72.

- Blau, P. (1964). Power and exchange in social life. New York: J Wiley & Sons, 352.

- Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of management review, 29(2), 203-221.

- Chambers, E. G., Foulon, M., Handfield-Jones, H., Hankin, S. M., & Michaels, E. G. (1998). The war for talent. McKinsey Quarterly, 44-57.

- Chen, Z. X., & Aryee, S. (2007). Delegation and Employee Work Outcomes: An Examination of the Cultural Context of Mediating Processes in China. The Academy of Management Journal, 226-238.

- Chen, C., & Tang, N. (2018). Does perceived inclusion matter in the workplace?. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(1), 43-57.

- Collins, C. J., & Kanar, A. M. (2014). Employer brand equity and recruitment research. The Oxford handbook of recruitment, 284-297.

- Dai, L., & Chen, Y. (2015). A systematic review of perceived insider status. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 3(02), 66.

- Danish, R. Q., & Usman, A. (2010). Impact of reward and recognition on job satisfaction and motivation: An empirical study from Pakistan. International journal of business and management, 5(2), 159.

- Davies, G. (2008). Employer branding and its influence on managers. European Journal of Marketing, 42(5/6), 667-681.

- Ding, C. G., & Shen, C. K. (2017). Perceived organizational support, participation in decision making, and perceived insider status for contract workers: A case study. Management Decision, 55(2), 413-426.

- Dobbs, R., Madgavkar, A., Barton, D., Labaye, E., Manyika, J., Roxburgh, C., ... & Madhav, S. (2012). The world at work: Jobs, pay, and skills for 3.5 billion people (Vol. 28). Greater Los Angeles: McKinsey Global Institute.

- Edwards, M. R. (2009). An integrative review of employer branding and OB theory. Personnel review, 39(1), 5-23.

- Fey, C. F., Björkman, I., & Pavlovskaya, A. (2000). The effect of human resource management practices on firm performance in Russia. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(1), 1-18.

- Fey, C. F., & Björkman, I. (2001). The effect of human resource management practices on MNC subsidiary performance in Russia. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1), 59-75.

- Fulmer, I. S., Gerhart, B., & Scott, K. S. (2003). Are the 100 best better? An empirical investigation of the relationship between being a “great place to work” and firm performance. Personnel Psychology, 56(4), 965-993.

- Gungordu, A., Ekmekcioglu, E. B., & Simsek, T. (2014). An empirical study on employer branding in the context of internal marketing. Journal of Management Marketing and Logistics, 1(1), 1-15.

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. 1998. Upper Saddle River.

- Heger, B. K. (2007). Linking the employment value proposition (EVP) to employee engagement and business outcomes: Preliminary findings from a linkage research pilot study. Organization Development Journal, 25(2), P121.

- Hui, C., Lee, C., & Wang, H. (2015). Organizational inducements and employee citizenship behavior: The mediating role of perceived insider status and the moderating role of collectivism. Human Resource Management, 54(3), 439-456.

- K. Ito, J., M. Brotheridge, C., & McFarland, K. (2013). Examining how preferences for employer branding attributes differ from entry to exit and how they relate to commitment, satisfaction, and retention. Career Development International, 18(7), 732-752.

- Kaiser, H. F., & Rice, J. (1974). Little jiffy, mark IV. Educational and psychological measurement, 34(1), 111-117.

- Katua, N. T. (2015). Effect of Training and Development Strategies on the Performance of Commercial Banks in Kenya. Journal of Educational Policy and Entrepreneurial Research, 2(7), 28-53.

- Kirkman, B. L., & Rosen, B. (1999). Beyond self-management: Antecedents and consequences of team empowerment. Academy of Management journal, 42(1), 58-74.

- Knox, S., & Freeman, C. (2006). Measuring and managing employer brand image in the service industry. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(7-8), 695-716.

- Leekha Chhabra, N., & Sharma, S. (2014). Employer branding: strategy for improving employer attractiveness. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 22(1), 48-60.

- Lievens, F., & Highhouse, S. (2003). The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company's attractiveness as an employer. Personnel Psychology, 56(1), 75-102.

- Lievens, F., Van Hoye, G., & Anseel, F. (2007). Organizational identity and employer image: towards a unifying framework. British Journal of Management, 18(s1), S45-S59.

- Lievens, F., & Slaughter, J. E. (2016). Employer image and employer branding: What we know and what we need to know. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3, 407-440.

- Masterson, S. S., & Stamper, C. L. (2003). Perceived organizational membership: An aggregate framework representing the employee–organization relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(5), 473-490.

- March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations.

- Mayson, S., & Barrett, R. (2006). The ‘science’ and ‘practice’ of HRM in small firms. Human resource management review, 16(4), 447-455.

- Maxwell, R., & Knox, S. (2009). Motivating employees to" live the brand": a comparative case study of employer brand attractiveness within the firm. Journal of marketing management, 25(9-10), 893-907.

- Mirap, S. O. (2008). Algılanan Aidiyet Durumunun Görev Performansı, Bağlamsal Performans Ve Toplam Performansa Etkilerini Ölçmeye Yönelik Özel Sağlık Kurumlarında Bir Araştırma. Yönetim ve Organizasyon Kongresi (16-18 Mayıs), İstanbul.

- Neves, P., & Eisenberger, R. (2012). Management communication and employee performance: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Human Performance, 25(5), 452-464.

- Pao-Long, C., & Wei-Ling, C. (2002). The effect of human resource management practices on firm performance: Empirical evidence from high-tech firms in Taiwan. International Journal of Management, 19(4), 622.

- Pearce, J. L., & Randel, A. E. (2004). Expectations of organizational mobility, workplace social inclusion, and employee job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(1), 81-98.

- Piyachat, B., Chanongkorn, K., & Panisa, M. (2014). The Mediate Effect of Employee Engagement on the Relationship between Perceived Employer Branding and Discretionary Effort. DLSU Business & Economics Review, 24(1).

- Rampl, L. V. (2014). How to become an employer of choice: transforming employer brand associations into employer first-choice brands. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(13-14), 1486-1504.

- Schlager, T., Bodderas, M., Maas, P., & Luc Cachelin, J. (2011). The influence of the employer brand on employee attitudes relevant for service branding: an empirical investigation. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(7), 497-508.

- Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Holcombe Ehrhart, K., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262-1289.

- Shore, L. M., Cleveland, J. N., & Sanchez, D. (2017). Inclusive workplaces: A review and model. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 176-189.

- Sigler, T. H., & Pearson, C. M. (2000). Creating an empowering culture: examining the relationship between organizational culture and perceptions of empowerment. Journal of quality management, 5(1), 27-52.

- Sivertzen, A. M., Nilsen, E. R., & Olafsen, A. H. (2013). Employer branding: employer attractiveness and the use of social media. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 22(7), 473-483.

- Stamper, C. L., & Masterson, S. S. (2002). Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 23(8), 875-894.

- Van Hoye, G., Bas, T., Cromheecke, S., & Lievens, F. (2013). The instrumental and symbolic dimensions of organisations' image as an employer: A large‐scale field study on employer branding in Turkey. Applied Psychology,62(4), 543-557.

- Wahba, M., & Elmanadily, D. (2015). Employer branding impact on employee behavıor and attitudes applied study on pharmatecual ın Egypt. International Journal of Management and Sustainability, 4(6), 145.

- Wang, H., Feng, J., Prevellie, P., & Wu, K. (2017). Why do I contribute when I am an “insider”? A moderated mediation approach to perceived insider status and employee’s innovative behavior. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 30(7), 1184-1197.

- Xiong Chen, Z., & Aryee, S. (2007). Delegation and employee work outcomes: An examination of the cultural context of mediating processes in China. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 226-238.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-053-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

54

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-884

Subjects

Business, Innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Tatar, B., & Erdil, O. (2019). Feeling Insider And Performing Better: The Importance Of Employer Brand. In M. Özşahin, & T. Hıdırlar (Eds.), New Challenges in Leadership and Technology Management, vol 54. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 512-525). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.02.43