Abstract

It is an undeniable fact that organizational managers need information from the employees in order to be able to respond to rapidly changing market conditions and to make the right decisions. The information may sometimes be new ideas, thoughts, and sometimes there are opposite opinions or dissatisfaction. A number of behaviors, events or situations play a role in the organization when members of the organization fall into disagreement with managers. The case of such separation of opinions emerging within the organization is called as organizational dissent. Organizational dissent emerges in the organizational behaviour field as a concept to be examined thoroughly. The current study attempts to identify the relationship between organizational dissent and ethical climate. The study also examines the joint effect of organizational dissent and ethical climate on turnover intention. For this aim, we collected data from 156 employees working in the banking industry in Turkey. Results of correlation analyses showed that there are significantly negative relationships between articulated dissent and caring climate and principle focus climate. Turnover intention is found to be significantly positively correlated with articulated dissent and implicit dissent and significantly negatively correlated with caring climate and principle focus climate. Implicit dissent and articulated dissent significantly positively effect turnover intentions and caring climate and principle focus climate significantly negatively effect turnover intentions. Theoretical and managerial implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: Organizational dissentarticulated dissentimplicit dissentcaring climateprinciple focus climateturnover intention

Introduction

Despite the fact that it is desirable for employees to adopt business goals and objectives, employees are not expected to comply with all the decisions, policies and practices unconditionally. There may be some decisions and policies that do not satisfy employees and that are uncomfortable or inappropriate for them. It is a requirement of the democratic management style that employees can clearly express their disagreement to the relevant units or management. To establish and maintain a democratic environment within the organization, understanding employee dissent is critical. Expressing disagreement without fear of punishment or retaliation is a democratic ideal (Kassing, 1997).

Organizational dissent is a risky and complex structure so employees must consider strategically to whom and how they express their disagreement. According to Kassing, employees express their dissent by three strategies: articulated, latent, or displaced (Kassing, 1997; 1998). Articulated dissent includes expressing disagreement to supervisors and management (upward). Latent dissent involves aggressive communication of dissent to coworkers, especially others who are experiencing frustration. Displaced dissent occurs when employees express their disagreement to individuals outside the organization such as family and friends (Payne, 2007).

An organization, sub-unit or working group can be composed of many types of climate, including the ethical climate (Schneider, 1975; Schwepker, 2001). Ethical climate refers to common perceptions about organizational practices and procedures that have ethical content and classified into 5 different sub-types: Caring, Law and Code, Rules, Instrumental, and Independent. Employees’ perceptions of their organizational climates also affect the manner and the subject in which employees choose to express dissent. When dissent is suppressed in organizations employees tend to be silent and only dissent in response to clearly unethical issues (Kassing, 2008). Organizational culture and climate can promote or resist organizational dissent (Kassing, 1998; 2009b). In order to understand which types of ethical climate encourage which type of organizational dissent, this study investigates the relationship between organization dissent and ethical climates.

One of the important work outcomes turnover intentions may be defined as the intention of employees to quit their organization. Kassing examined how organizational dissent related to intention to leave and found that an employee’s expression of lateral and displaced dissent indicated intention to leave one’s organization while there is a negative relationship between upward dissent and intention to leave (Kassing, Piemonte, Goman, & Mitchell, 2012). Mulki, Jaramillo and Locander, (2006) examined which ethical climate affected turnover intention. He found that ethical climate reduces turnover intentions. Also, Scwepker (2001) found that perceptions of a positive ethical climate is associated with job satisfaction and organizational commitment positively and with turnover intention negatively. Concordantly, in this study we also examined the joint effect of organizational dissent and ethical climate on turnover intentions.

In order to understand the interrelation between organizational dissent and ethical climate, and their joint effect on employees’ turnover intentions, we conducted a field research by using the survey methodology on a sample of employees working in banking industry. Next section we provide a literature review on organizational dissent, ethical climate and turnover intention. Following the literature review, research methodology and data analysis are presented. The paper is finished by concluding remarks and research implications.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Organizational Dissent

Employees’ expressing their disagreement or contradictory opinions about workplace practices, policies and practices called organizational or employee dissent (Kassing, 1998). Sprague & Ruud (1988) stated that, organizational dissent can be regarded as “a moral obligation, a political right, an enlightened management practice, a minor inconvenience, or a punishable violation of loyalty’’.

According to Exit-Voice-Loyalty (EVL) Model of Dissatisfaction, employees may use different strategies to express their dissatisfaction with a company. These strategies are related to whom employees express their dissatisfaction and/or opposing ideas (Kassing, 1997). Articulated dissent strategy involves expressing dissent openly and clearly within organizations to audiences that can effectively influence organizational adjustment. If employees desire to voice their disagreements but they cannot effectively express themselves then latent dissent occurs. As a result of their insufficiency they become frustrated and resort to expressing their contradictory opinions and disagreements aggressively to ineffectual audiences across organizations or in concert with other frustrated employees. Latent dissent readily exists but it is not observable to some organizational audiences. Displaced dissent involves expressing dissent to some external audiences like non-work friends, spouses or partners, strangers, and family members, but not the media or political sources sought by whistle-blowers (Kassing &Avtgis, 1999).

Kassing’s model of dissent has four components: 1) triggering agent, 2) strategy selection influences, 3) strategy selection and 4) expressed dissent. The model suggests that the process of organizational dissent begins with a triggering-event (Kassing & Armstrong, 2002). Dissent happens when the triggering event exceeds employees’ tolerance for dissent (Redding, 1985). In their study Kassing & Armstrong (2002), have explained the triggering events that lead employees to dissent as employee treatment, organizational change, decision making, inefficiency, role/responsibility, resources, ethics, performance evaluation and preventing harm.

According to Kassing’s (1997) model dissent is categorized as individual, relational, and organizational influences/factors. These factors affect employees’ dissent expression strategy. Individual influences are about behaviors within the organization. Dissent first begins at a personal level. Dissent means feeling apart or distanced from one’s organization (Kassing, 1997). Individual factors contains predispositions/traits, association /affiliation with their organization and their position. Verbal aggressiveness, argumentativeness, locus of control is some research examples of employees’ predispositions/traits (Kassing & Avtgis, 1999; 2001). In addition employees’ willingness to dissent is influenced by senses of powerlessness and avoiding conflict (Sprague & Ruud, 1988). Other individual issues related with dissent expression are employee commitment, employee satisfaction, organizational identification (Kassing, 2009, p.61). Relational influences contain the types and quality of associations employees maintain within organizations (Kassing, 2008). Employees prefer to express their disagreement in face-to-face interactions with their supervisors (Sprague & Ruud, 1988). Employees focus on the well-being of their coworkers when expressing their dissent (Kassing & Armstrong, 2002). If employees perceive high quality relationship with their supervisors, they tend to dissent to their supervisor, but if they perceive low quality relationship with their supervisors, they express their disagreement to coworkers (Kassing, 2009b). So, relationships between organizational members can be considered as an important determinant of how employees’ choose to express dissent (Kassing, 2008 ). Organizational influences, includes how employees perceive and understand their organizational climates. Organizations’ responses to dissent provide feedback to following dissenters concerning whether or not they should expect to be rewarded, ignored, or punished (Kassing, 2008). Organizational culture and climate can promote or resist organizational dissent (Kassing, 1998; 2009b). Through creating communication climates, organizations foster or suppress dissent. Kassing (2009a) found that perceived more freedom of speech existed in the organization caused to more highly identified employees and more upward dissent. Besides, lateral dissent reduces when employees observe more perceived fairness regarding organizational decision making (Kassing & McDowell, 2008). Employees’ perceptions of their organizational climates also affect the manner and the subject in which employees choose to express dissent. When dissent is suppressed in organizations employees tend to be silent and only dissent in response to clearly unethical issues (Kassing, 2008).

Ethical Work Climate (EWC)

Unethical behaviors in organizations have become an important and costly problem in the workplace and even in society. Almost every day in recent years, news are filled with about corporate managers and employees' unethical behavior. (Jones & Kavanang, 1996) Corporate scandals (or lapses in corporate ethical behavior) such as fraudulent bookkeeping, payment of bribes, the misuse of confidential information, embezzlement, marketing of dangerous products, discrimination against minorities, insider trading, and corporate fraud have created awareness about the importance of an ethical work climate. The creation of ethical work climate is very important for all organizations and employees. (DeConinck, 2011; Jones & Kavanangh, 1996) Also, there is growing belief that organizations are social actors that are responsible for the ethical or unethical behaviors of their employees (Victor and Cullen, 1988). Since organizations affect employees' ethical behavior, managers can change the ethical climate of employees in the workplace where inappropriate behavior is common; thereby they can enable employees to demonstrate ethical behavior. (Wimbush, Shepard, & Markham, 1997).

Ethical climate is a kind of work climate that can be defined as a group of settled climates that reflects organizational procedures, policies and ethical practices. Ethical climate is also the perception of what is right behavior. So it becomes a psychological mechanism in which ethical issues are managed. The ethical climate influences both decision making and subsequent behavior in response to ethical dilemmas. (Martin & Cullen, 2006). In other word ethical climate is generally defined as a psychological structure resulting from the aggregation of individual perceptions of what are the ethical behaviors in the organization. Therefore, the ethical climate is usually defined by the group and defines what ethical and unethical behaviors are for the group and the individual and how ethical issues are managed. Understanding the factors that influence the perception of ethical behavior in an organization (i.e., public, profit-oriented and non-profit oriented) is crucial to managers in promoting ethical behavior against unethical behavior. (Malloy & Agarwal, 2001)

Although the lack of a consensus on a specific ethical climate type, Victor and Cullen have introduced the concept of ethical climate to explain and predict ethical behavior in organizations and have conducted studies on the ethical climate of companies (Suar & Khantia, 2004). Victor and Cullen (1988) developed a two-dimensional Ethical Climate Model to explain the concept of ethical climate in their study. The first dimension of the model shows the ethical criteria (egoism, benevolence, principle) in organizational decision making. The second dimension shows the locus of analysis (individual, local, cosmopolitan) used as a referent in ethical decisions. (Victor & Cullen, 1988) When these two dimensions that have three criteria are cross-classified nine theoretical types of ethical climates appear which are self-interest, company profit, efficiency, friendship, team interest, social responsibility, personal morality, company rules and procedures, laws and professional codes. These nine factors were consolidated in seven or five dimensions by factor analysis studies conducted in various periods. As a result of ongoing work, it was more appropriate to compose these factors in total five dimensions. The five dimensions can be summarized as follows: (Martin & Cullen, 2006)

Instrumentalism: In this type of ethical climate, personal interest is raised to the highest level. Also, personal and institutional interests influence ethical decisions.

Caring: The well-being of individuals or the organization as a whole is taken into account. It focuses on friendship, team spirit and social responsibility. It is also accepted that decisions should be made for the benefit of the society as a whole as well as for the benefit of the persons in the organization

Independence: Employees with such an ethical climate structure believe that when they have to make an ethical decision, they must make decisions based on their personal moral beliefs.

Rules: In these climates, ethical decision-making is guided by the individual's commitment to rules and principles. They are expected from individuals within the organization to fully comply with the organizational rules and obligations

Law and Code: This type of climate requires employees to obey the codes of another authority or profession. Employees must make decisions by connecting to external systems such as the law. Organizations managed by laws and codes are based on external standards and principles in decision making.

Wang and Hsieh (2013) investigates the relationships between ethical climates and employee silence in their study and found significant relationships between employee silence and instrumental and caring climates. Employees are encouraged to behave and make decisions in caring climates. The norm of benevolence in a caring climate stimulates employees’ prosocial motive then employees feel that they should express their disagreement about work-related problems that may result in harmful consequences to all in the organization. In caring climates organizations value their employees’ contributions more, so it can reduce employees’ feelings of futility when expressing their opinions about work-related problems. In caring climates employees will be less fearful of the possible negative personal consequences of speaking up about work-related problems, because a benign and caring organizational atmosphere provides psychological safety for expressing their concerns (Wang & Hsieh, 2013). They also examined the relationship between rules and law & codes climates and employee silence, but found no significant relationship. Nevertheless, rules or law & code climates may support reporting violations of organizational rules (Wimbush, Shepard & Jon, 1994). Rules and law & code climates is associated with organizational punishment for violating the rules, codes, or laws. So, employees feel hesitant to express their work-related problems in order to not to put their colleagues or organization in trouble (Somers, 2001). Rules and law & codes climates may be less effective in reducing employee silence because harmful consequences may occur for others when employees speak up about work-related problems (Wang & Hsieh, 2013).

Organizational dissent is defined as expressing disagreement or contradictory opinions about workplace practices, policies and operations and it can be accepted as opposite to employee silence which refers to the intentional withholding of information, opinions, suggestions, or concerns about potentially important organizational issues (Pinder & Harlos, 2001; Dyne, Van, Ang, & Botero, 2003). Accordingly, we propose significant relationships between organizational dissent and ethical climates.

Turnover Intention

Turnover intention is defined as a conscious and deliberate willfulness to leave the organization (Tett &Meyer, 1993). March & Simon (1958) handled the outcome of the interaction between “perceived desirability of movement from the organization" and "perceived ease of movement from the organization" as turnover (Bowen, 1982). Adopted from Kim et.al (1996), intention to quit (stay) can be defined as the extent to which an employee plans to discontinue (continue) the relationship with his or her employer (Kim, Price, Mueller& Watson, 1996). Even though employees’ “intention to leave” is reflected a signal of quitting, there are no dependable findings with regard to its value as a predictor of actual turnover (Weisberg, 1994).

Kassing examined how organizational dissent related to intention to leave and found that dissent expressed to non-management audiences associated with intention to leave. Results showed that, an employee’s expression of lateral and displaced dissent indicated intention to leave one’s organization while there is a negative relationship between upward dissent and intention to leave (Kassing, et.al, 2012).

Mulki et.al (2006), examined which ethical climate affected turnover intentions. He found that ethical climate reduces turnover intention. Also, Scwepker (2001) found that perceptions of a positive ethical climate associated with their job satisfaction and organizational commitment positively and with turnover intention negatively.

As we mentioned before, extant literature covers some studies investigating the effect of organizational dissent’s and ethical climate’s independent effects on turnover intentions. However, to the author’ knowledge, there is not any particular study examining the joint effects of organizational dissent and ethical climate on turnover intentions. Accordingly, in this study we investigate the joint effects of perceived organizational dissent and ethical climate on turnover intentions. Next section provides the research methodology, research hypothesis, data analyses and results.

Research Method

Research Goal

The main objective of this study is examining the relationship between organizational dissent and ethical climate and their joint effects on turnover intentions. In order to probe the interrelations between these variables, we conducted a field study by employing survey methodology.

Research Hypotheses

Based on the relevant literature, we proposed the following hypotheses:

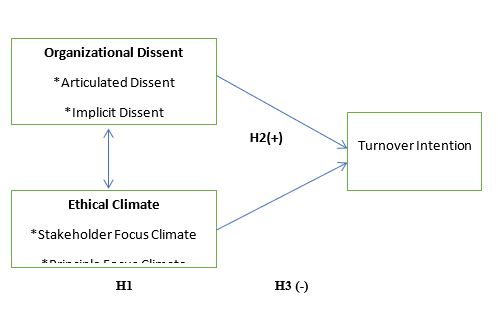

H1: There is a significant relationship between organizational dissent and ethical climate.

H2: Perceived organizational dissent significantly positively effects turnover intention.

H3: Perceived ethical climate significantly negatively effects turnover intention.

Research Model

The following diagram shows the research model and proposed hypotheses

Sample and Data Collection

Data is collected by an online survey comprising several questions measuring perceived organizational dissent, ethical climate and turnover intentions. Through a convenient sampling process, 156 individuals who were working in banking sector in north-western Turkey participated in this study by voluntarily filling the online questionnaire. Questionnaires are coded and entered into a SPSS spreadsheet in order to perform the data analyses.

Organizational Dissent was measured by 24 items taken from the “Organizational Dissent Scale” developed by Jeffrey W. Kassing (Kassing, 1998). Ethical Climate was measured by 36 items adapted from Cullen et al., 1993. Turnover intention was measured by 3 items adapted from Angle & Perry (1981) and Jenkins (1993). Participants were requested to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with the statements in all scales using five-point Likert type scales (1= strongly disagree; 5= strongly agree). After performing exploratory factor analyses and reliability analyses, research hypotheses are tested by correlation and regression analyses.

Analyses and Results

The mean age of the participants was 35.9 years and 50% were female; 80,8 % were married, most of them had graduate (74,4%) and postgraduate degrees (13,4%). 85,9% were working for private banks. Mean organizational tenure was 8,66 years (range: 1-28) and mean tenure of working for the current position was 5,30 years (range: 1-20).

Before testing the research hypotheses, we made some preliminary analyses to control the dimensionality and reliability of the scales. Scale dimensionality was controlled by principal component analysis with varimax rotation and a factor extraction according to the mineigen criterion (i.e. all factors with eigenvalues of greater than 1) was employed. Scale reliability was assessed by internal consistency using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. Table

After deleting some items dues to low factor loading and negative contribution to scale reliability, organizational dissent scale extracted two factors explaining 62,3% of the total variation in the scale. Six items were loaded on the first factor named “articulated dissent” reflecting employees’ explicit dissent behavior when they express their dissent openly and clearly within organizations to audiences that can effectively influence organizational adjustment. This factor has a reliability coefficient of 0,87. Five items were loaded on the second factor named “implicit dissent” reflecting employees’ latent dissent behavior when they desire to voice their opinions but they become frustrated because they couldn’t effectively express themselves. This factor has a reliability coefficient of 0,84.

In a similar manner, exploratory factor analysis on ethical climate scale resulted two factors explaining 75,8% of the total variation in the scale. Ten items were loaded on the first factor named “Caring Climate” reflecting employees’ beliefs about the organization's ethical policies and practices are based on an overarching concern for organizational members as well as society at large (Mulki et al, 2006, p.20). This factor has a reliability coefficient of 0,95. Five items were loaded on the second factor named “Principle Focus Climate” reflecting the climate of law and code which is based on the perception that the organization supports principled decision-making based on external codes such as the law, the Bible, or professional codes of conduct and the rules climate relates to a principled climate governed by rules and regulation that guide ethical behaviour. This factor has a reliability coefficient of 0,90.

Principal components analysis suggested a single factor for turnover intention scale, which explained 73,4% of the total variance. All of the scale items loaded heavily on a single factor. This factor has a reliability coefficient of 0,81.

Based on the results from principal components and reliability analyses, we computed five composite variables by averaging the items under each factor in order to be used to test the research hypotheses. The means, standard deviations, and interrelations of all composite variables are presented in Table

In the next stage, a series of (hierarchical) regression analyses are employed to test the effects of organizational dissent and organizational climate on turnover intentions (H2 and H3). By doing so, we expected to understand the relative portions of unique variances in the respondents’ turnover intentions accounted for by organizational dissent and organizational climate. The hierarchical regression analysis was performed in two steps. In the first step, two dimensions of organizational dissent were entered in the regression model as predictors. In the second step, two ethical climate dimensions were included in the model in order to see the changes in the parameter estimates. Table

Organizational dissent positively affects turnover intentions. Two dimension of organizational dissent account for 22% of the variance in turnover intentions (p<0,001). After the inclusion of ethical climate dimensions in the second stage, the amount of explained variance in turnover intentions increased by 17,5% to an overall level of 39,8%. Implicit dissent significantly positively effects turnover intentions (β=0,441 p<0,01). Articulated dissent also positively effects turnover intentions with a marginally significant level (β=0,136 p=0,061). Thus, the second hypothesis proposing that perceptions of organizational dissent significantly positively affects turnover intentions (H2) was supported.

Yet, inclusion of perceived ethical climate dimensions in the regression model improved the predictive power but reduced the standardized regression coefficient linking articulated dissent to turnover intentions from 0,136 to a nonsignificant level of -,001. Caring climate significantly negatively effects turnover intentions (β=-0,349 p<0,01). Principle Focus Climate also significantly negatively effects turnover intentions (β=0,226 p=0,004). These results provide evidence to confirm our third hypothesis proposing that perceptions of organizational climate significantly negatively affect turnover intentions. (H3) was also supported. The next section provides the conclusion and implication of these findings.

Conclusion and Implications

In this study we examined the relationship between organizational dissent and ethical climate. We also examined the joint effect of organizational dissent and ethical climate on turnover intention. For this aim, we collected data from a convenience sample of employees working in the banking industry. Respondents’ perception of organizational dissent, ethical climates and turnover intention are measured by multi item scales. Factor structure of the organizational dissent scale was analysed by principal component analysis. Factor analysis revealed two factors (articulated dissent, implicit dissent) different from the original three factor structure (Kassing, 1998). We also analyzed factor structure of ethical climate scale by exploratory factor analysis and found two ethical climate types (caring, principle focus). Principal components analysis suggested a single factor for turnover intention scale. Based on the results from principal components and reliability analyses, we computed five composite variables by averaging the items under each factor in order to be used to test the research hypotheses. Correlations among all variables reveal that there are significantly negative relationships between articulated dissent and caring climate and principle focus climate. Turnover intention is found to be significantly positively correlated with articulated dissent and implicit dissent. Turnover intention is found to be significantly negatively correlated with caring organizational climate and principle focus climate Hence, our first hypothesis (H1) proposing a significant relationship between organizational dissent and ethical climate was supported. In order to test H2 and H3, series of (hierarchical) regression analyses are employed to see the effects of organizational dissent and organizational climate on turnover intentions. As a result, implicit dissent and articulated dissent, both significantly positively effect turnover intentions and (H2) was supported. Caring climate significantly negatively affects turnover intentions. Also, Principle Focus Climate significantly negatively affects turnover intentions, so (H3) was also supported.

The findings of this study demonstrated that negative relationships between perceived caring climate and both articulated and implicit dissents. A negative relationship between the caring climate and the articulated dissent is not an expected finding. Because caring climates are employee focused climates and in such climates it is expected that open communication will dominate. Also negative relationships between perceived principle focus climate and both articulated and implicit dissents. Principle focus climates are associated with organizational punishment for violating the rules, codes, or laws. So, employees feel hesitant to express their work-related problems in order to not to put their colleagues or organization in trouble (Somers, 2001). These climates may be less effective in reducing employee silence because harmful consequences may occur for others when employees speak up about work-related problems (Wang & Hsieh, 2013). So this result was also not expected. These unexpected results may be because of the management approach in the banking sector. Although participatory management practices are included in banking sector, it can be assumed that the hierarchical management approach is dominant and the organizational dissent is perceived as risky in general because of fear of punishment.

Dissent in organizations was perceived as a negative phenomenon. We found positive relationships between both articulated and implicit dissents and turnover intention, although the extant literature suggested a negative relationship between upward (articulated) dissent and turnover intention (Kassing, et al, 2012). This finding can be explained by the notion that dissent is perceived as a conflict and disturbing condition for employees. Managers can cope with this problem by creating participatory organizational climates where open communication and constructive opposition are encouraged.

The last finding of this study is both caring climate and principle focus climate significantly negatively affects turnover intentions. As we mentioned before caring climates are employee focus climates. Principle focus climate includes law& code and rules climates. When employees’ actions are guided by rules and procedures, they perceive less role conflict, find their job more meaningful, and display positive attitudes and behaviors in the organization (Cullen, Victor & Bronson, 2003; Martin & Cullen, 2006; Weeks, Loe, Chonko, Martinez & Wakefield, 2006). It is also possible to say that law and codes protect the rights of employees. The negative effect of principle focus climate on turnover intention can be attributed to the results. These findings must be interpreted with the current socio-economic conditions in Turkey, where high economic and political instability peaked unemployment levels during the data collection process.

This study has some limitations. It was conducted with the use of a convenience sample. There is a need to replicate this research with the use of more representative random samples. Future studies would gain external validity by using probability samples of wider populations. Replicating the study in different contexts both concerning the public and private ownership status and the type of industry may also provide additional insights. In this research both organizational dissent and ethical climate are discussed in terms of their two dimensions. Further research can examine other dimensions to contribute to the literature as well.

References

- Angle, H. L., & Perry, J. L. (1981). An Empirical Assessment of Organizational Commitment and Organizational Effectiveness Author (s): Harold L . Angle and James L .Perry Published by : Sage Publications, Inc on behalf of the Johnson Graduate School of Management , Cornell University S, 26(1), 1–14.

- Bowen, D. (1982). Some Unintended Consequences of Intention to Quit. The Academy of Management Review, 7(2), 205-211. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/257298.

- Cullen, J. B., Parboteeah & Victor B. (2003). The Effects of Ethical Climates on Organizational Commitment : A Two- Study Analysis, Journal of Business ethics (January). https://doi.org/10.1023/A

- Cullen, J. B., Victor, B., & Bronson, J. W. (1993). Ethical Climate Question- naire: An Assesment of its Development and Validity. Psychological Reports, 73, 667–674. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.73.2.667

- DeConinck, J. B. (2011). The effects of ethical climate on organizational identification, supervisory trust, and turnover among salespeople. Journal of Business Research, 64(6), 617–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.06.014

- Dyne, L. Van, Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing Employee Silence and Employee Voice as Multidimensional Constructs*. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00384

- Jenkins, J. M., Journal, S., Jan, N. (1993). Self-Monitoring and Turnover: The Impact of Personality on Intent to Leave, 14(1), 83–91.

- Jones, G. E., & Kavanagh, M. J. (1996). An experimental examination of the effects of individual and situational factors on unethical behavioral intentions in the workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(5), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00381927

- Kassing, J. W. (1997). Articulating, antagonizing, and displacing: A model of employee dissent. Communication Studies, 48(4), 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510979709368510

- Kassing, J. W. (2008). Consider This: A Comparison of Factors Contributing to Employees’ Expressions of Dissent. Communication Quarterly, 56(3), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370802240825

- Kassing, J. W. (2009a). Exploring the relationship between workplace freedom of speech, organizational identification, and employee dissent. Communication Research Reports, 17(4), 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090009388787

- Kassing, J. W. (2009b). Investigating the relationship between superior‐subordinate relationship quality and employee dissent. Communication Research Reports, 17(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090009388751

- Kassing, J. W., & Armstrong, T. A. (2002). Someone’s going to hear about this: Examining the association between dissent-triggering events and employees’ dissent expression. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(1), 39-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318902161002

- Kassing, J. W., & Avtgis, T. A. (1999). Examining the relationship between organizational dissent and aggresive communication. Management Communication Quarterly, 13(1), 100–115.

- Kassing, J. W., & Avtgis, T. A. (2001). Dissension in the Organization as it Relates to Control Expectancies, 18(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090109384789

- Kassing, J. W., & McDowell, Z. J. (2008). Disagreeing about What’s Fair: Exploring the Relationship between Perceptions of Justice and Employee Dissent. Communication Research Reports, 25(Kassing, J. W., Piemonte, N. M., Goman, C. C., & Mitchell, C. A. (2012). Dissent Expression as an Indicator of Work Engagement and Intention to Leave. Journal of Business Communication, 49(3), 237–253. 1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090701831784

- Kassing, J. W., Piemonte, N. M., Goman, C. C., & Mitchell, C. A. (2012). Dissent Expression as an Indicator of Work Engagement and Intention to Leave. Journal of Business Communication, 49(3), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943612446751

- Kim, S. W., Price, J. L., Mueller, C. W., & Watson, T. W. (1996). The determinants of career intent among physicians at a U.S. Air Force hospital. Human Relations, 49(7), 947–976.

- Malloy, D. C. & Agarwal J.(2001). Ethical Climate in Nonprofit Organizations Propositions and Implications, Nonprofit Management & Leadership, Volume: 12, No: 1, pp.39-54.

- Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9084-7

- March, J.G. and Simon, H.A., (1958), Organizations, New York, Wiley.

- Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, F., & Locander, W. B. (2006). Effects of Ethical Climate and Supervisory Trust on Salesperson’S Job Attitudes and Intentions to Quit. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.2753/PSS0885-3134260102

- Payne, Holly J., (2007), The Role of Organization-Based Self-Esteem in Employee Dissent Expression, Communication Research Reports, 24(3), 235-240, . https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(01)20007-3

- Pinder, C. C., & Harlos, K. P. (n.d.). Employee Silence : Quiescence and Acquiescence as Responses to Perceived Injustice, 20, 331-369.

- Redding, W.C. (1985), Rocking Boats, Blowing Whistles, and Teaching Speech Communication. Communication Education, 34(3), 245-258.

- Schneider B.(1975), Organizational climate. An essay. Pers Psychol;28, 447–79.

- Schwepker, C. H. (2001). Ethical climate’s relationship to job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention in the salesforce. Journal of Business Research, 54(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00125-9

- Somers, M. J. (2001). Ethical Codes of Conduct and Organizational Context: A Study of the Relationship Between Codes of Conduct, Employee Behavior and Organizational Values, 185–195.

- Sprague, J., & Ruud, G. L. (1988). Boat-rocking in the high-technology culture. American Behavioral Scientist, 32(2), 169-193, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764288032002009

- Suar, D & Khuntıa R. (2004). Does Ethical Climate Influence Unethical Practices and Work Behaviour? Journal of Human Values, Volume:10 No:1, pp: 11 -21.

- Tett, R. P. & Meyer J.P. (1993), Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta‐analytic findings, Personnel Psychology, Volume46, Issue2, June 1993, pp. 259-293.

- Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The Organizational Bases of Ethical Work Climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392857

- Wang, Y. De, & Hsieh, H. H. (2013). Organizational ethical climate, perceived organizational support, and employee silence: A cross-level investigation. Human Relations, 66(6), 783–802. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712460706

- Weeks, W. A., Loe, T. W., Chonko, L. B., Martinez, C. R., & Wakefield, K. (2006). Cognitive Moral Development and the Impact of Perceived Organizational Ethical Climate on the Search for Sales Force Excellence: A Cross-Cultural Study. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.2753/PSS0885-3134260207

- Weisberg, J.(1994), Measuring Workers’ Burnout and Intention to Leave, International Journal of Manpower, 15(1), pp. 4-14.

- Wimbush, J. C., Shepard, J. M., & Jon, M. (1994). Toward An Understanding Climate : Behavior of Ethical Behavior and Supervisory Influence. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(8), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00871811

- Wimbush, J. C., Shepard, J. M., & Markham, S. E. (1997). An empirical examination of the relationship between ethical climate and ethical climate in organizations, Journal of Business Ethics., 67–77.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-053-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

54

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-884

Subjects

Business, Innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Alniacik, E., & Erbas Kelebek, E. (2019). Relationship Between Organizational Dissent & Ethical Climate: Their Effects On Turnover Intentions. In M. Özşahin, & T. Hıdırlar (Eds.), New Challenges in Leadership and Technology Management, vol 54. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 432-445). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.02.37