Abstract

The present study examines several components which make up the portrait of a modern lawyer fluent in legal foreign language and deals with intraprofessional interactional competence. The study defines the mentioned competence and describes its component composition. The question is raised about the way and with the help of which means this competence can be formed. The author also considers and substantiates the model of a problem-oriented textbook module based on intercultural, contextual and discourse parameters, as well as the principle of interactivity, which presupposes, inter alia, a parallelization of professional pictures of the world. Furthermore, the described textbook should be isomorphic in its architecture to the professional activity of a lawyer, that is to say, its components are organized around a professional problem that is supposed to be solved with the help of suggested step-by-step algorithms. An efficiency verification of this model as part of the educational process at the Kutafin State Law University (MSAL) as well as Lobachevsky University in Nizhny Novgorod, enrolling a total of 16 law students learning legal French, was undertaken and discussed. In the course of the study, statistical processing and interpretation of quantitative indicators of the specified competence were carried out. Conclusions are drawn about the further implementation of the designed technology.

Keywords: Interactional competencelaw studentsproblem-based approachtextbook of foreign language for specific purposes

Introduction

A foreign language is a compulsory part of the curriculum for Russian law students at all three stages of their higher education. In general, the number of hours allocated for the study of a legal foreign language may vary depending on the priorities of the educational institution, but the target remains unchanged and consists in the formation of second language intercultural professional competence. Without going into specifics as to the structure of the latter we will point out that, given the social dimension of a legal profession, which implies an active interaction with customers from a non-legal background and colleagues, SL interactional competence turns out to be relevant.

A group of Russian researchers defines

Due to a clearly delineated communicative dimension of the legal profession, we consider that the description of a modern lawyer’s competencies in SL would not be complete without intra- and extraprofessional interactional competence. The necessity of this binary structure stems from the fact that in the course of their professional activity the lawyer has to interact both with his colleagues and with clients who are not aware of the specifics of procedural actions or of the peculiarities of law enforcement practice. This especially holds true for foreign clients seeking advice or comprehensive legal support, finding themselves in the context of Russian law. In our study, we define

For the purposes of this article, we will limit ourselves to the consideration of intraprofessional interactional competence of law students.

Problem Statement

The most relevant activities for a lawyer are law enforcement and expert consulting. The analysis of legal job offers (with mandatory knowledge of the French language) posted by recruiting agencies

It is no coincidence that some foreign studies emphasize the need to develop specialized interactive courses for law students (Pohjonen & Lindblom‐Ylänne, 2002), others identify gaps in the key competencies which any lawyer should possess (legal representation, client interviewing etc.), insisting on competence-based approach training (Turner, Bone, & Ashton, 2016). The Carnegie report also states that, being focused on “a heavily academic” case-dialogue method, law schools fail to provide effective support for developing ethical and social skills (The Carnegie foundation for the advancement of teaching, p. 6). In terms of teaching professionally-oriented foreign language there are suggestions regarding the use of simulations (theatricalization, legal business games) as a means of forming pragmatic competence (De Gioa & Marcon, 2016).

In this connection, the question arises as to whether the existing textbooks of a foreign (in our case, French) language for lawyers live up to the expectations of the labor market and the modern concept of training lawyers of the new generation.

The study of the existing French language textbooks for lawyers showed (Voskresenskaya, 2018) that their authors mainly focus on the assimilation of a certain amount of professional knowledge by the students, not paying due attention to the specifics of their future activities, as well as the general context, in which the acquired knowledge would be applied during interaction with foreign colleagues and clients. We may draw a conclusion that these textbooks are not aimed at the comprehensive formation of the above-mentioned skills.

The suggested design of the SL textbook for lawyers is intended to solve the problem associated with the development of social interactional skills highly demanded in the modern labor market.

The architecture of the textbook on legal communication is isomorphic to the professional activity of a lawyer and comprises a number of interdependent blocks. Since problem solving appears to be the most important skill according to the Statement of fundamental lawyering skills and professional values (American Bar Association. Section of Legal Education and Admission, p. 135), it becomes “the primary goal of legal education” (Stuckey, 2007, p. 6). This trend echoes with one of the main principles of professionally oriented language teaching in the domestic tradition, which presupposes strong communicative and problem-based dimensions, since professional skills are formed in conditions of group communication aimed at problem solving (Almazova, Baranova, & Khalyapina, 2017; Almazova, Eremin, & Rubtsova, 2016). That is why all the textbook components revolve around a legal problem:

a system-forming professional problem (in the case of intraprofessional competence, students were asked to inform their French peers about legal education in Russia, paying due attention to the similarities and differences with its French counterpart);

competency descriptors formulated on its (problem’s) basis (Table

an arsenal of linguodidactic tools, developed to prepare students for interaction on a step by step basis; it is during this interaction that the problem is expected to be solved (in our case, the lawyer-to-lawyer discourse will be relevant, and therefore there will be exercises to develop the skills of self-presentation, active listening, compensatory skills etc.);

the annexes (performing a supporting function), as well as control and self-assessment units (based on the target settings competency descriptors) comprise the final part of the textbook. The module ends with a control activity (meeting or round table) aimed at interaction with foreign law students (meeting or round table). It seemed important to us to redesign control and assessment activities in line with current trends (Tareva & Tarev, 2018) so that the students could have an opportunity to put their skills to the test in conditions of real face-to-face interaction with foreign peers, assess themselves, and, finally receive feedback not only from the teacher but also from partners in interaction.

Due to the fact that the textbook is built on different types of interaction (first of all – interaction between professional cultures; after all – between the subjects of these cultures) it is likely to promote the idea of communities of practice described by Lockwood (2013) enhancing the educational environment as well as fostering social learning.

Research Questions

Can a textbook designed in line with the ideology of problem-based and contextual approaches and considering the principle of interactivity, which consists in the parallelization of professional pictures of the world and the use of legal discourse as the main source of models of interaction, be an effective means of developing SL interactional competence of law students?

Purpose of the Study

The study is aimed at putting to the test the working hypothesis, according to which a textbook designed in line with the problem-based approach, taking into account discourse and professional parameters, may be a means of developing SL intraprofessional interactional competence.

Research Methods

The experimental training aimed at testing the efficiency of the designed module of the textbook lasted for one month and consisted of the following stages: input self-assessment, training, control activities with native speakers, complex output assessment involving several auditors. A total of 16 students from two Russian universities (Kutafin Moscow State Law University (MSAL) and Lobachevsky University) were enrolled in the training: 5 first-year and 6 second-year Bachelor programme students (MSAL), 1 Master programme student (MSAL) and 5 third-year Bachelor programme students (Lobachevsky University).

In order to assess the development of the intraprofessional interactional competence, the following methods were applied: a self-assessment (input stage) on specially designed descriptors with a corresponding scale; a comprehensive assessment (output stage) with the involvement of external experts (French law students, fellow teachers, students). In the latter case, the evaluation was based on similar descriptors.

Based on the level of language proficiency A2 (Council of Europe, 2018) and the objectives laid down in the textbook (to inform foreign colleagues about legal education in Russia), the descriptors of SL intraprofessional interactional competence were formulated as follows:

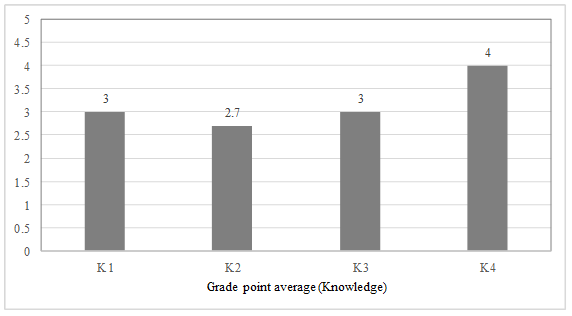

It is worth noting that in the case of the cognitive component (knowledge), the estimated scale established by us is half the one that was used to evaluate the pragmatic component, namely the skills (sub-competencies) due to the complexity of these formations, the need for a more nuanced approach in their assessment.

Findings

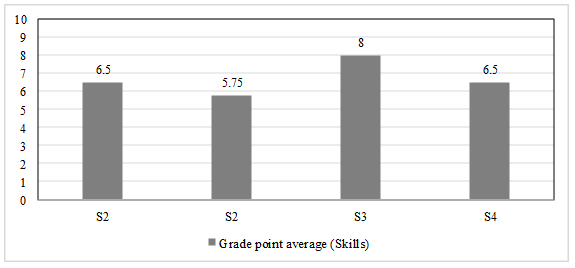

The quantitative data obtained in the course of self-assessment by the students or external evaluation by experts were subjected to statistical processing, tables and diagrams were compiled, objectively reflecting the evolution of intraprofessional interactional competence of students within a single topic. Statistical parameters. such as arithmetic mean, median, coefficient of asymmetry and standard deviation were implemented for self-diagnosis indicators at the pre-experimental stage using Microsoft Excel. The median was interpreted instead of the arithmetic mean when the coefficient of asymmetry was different from zero and therefore testified to the abnormality of the distribution. As may be seen in the diagrams (Figures

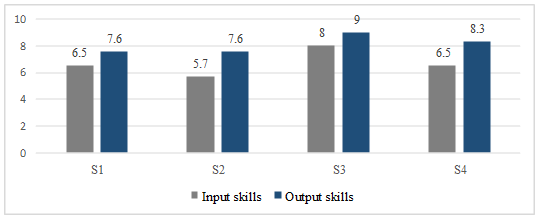

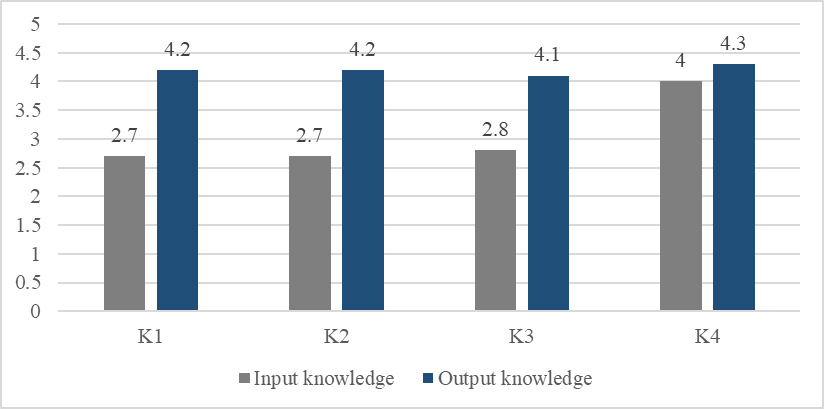

After the control activity (a round table with French students), the research participants were again asked to fill out a questionnaire, assessing their achievements after direct interaction with their foreign colleagues. At the same time, their performances were evaluated by external experts and communication partners. As a result, the average value of the components of the intraprofessional interactional competence based on both self - and external evaluation was calculated.

The comparative bar chart below, which is based on the input and output indicators, demonstrates the stable positive dynamics of all components of the described intraprofessional interactional competence.

The presented processed data allows to verify the efficiency of the designed technology (and, consequently, that of a textbook’s module, compiled on the basis of this technology), as a possible means of developing comprehensive intraprofessional interactional competence (improvements were recorded for all its components). At the same time, the positive dynamics of general trends do not always reflect the evolution of self-diagnosis indicators. Some students tended to underestimate their own scores after the control activity, which undoubtedly raises the question of the need to implement the procedure of self-diagnosis on a permanent basis so that the students get used to it, which is currently not the case in the system of higher education. It also might suggest the improvement of the applied procedures of self-diagnosis.

We also note that the range of standard deviation (S) characterizing the spread of values relative to the mean is narrower at the post-experimental stage: 0.9 ⩽ S pre-exp. ⩽ 1.9 vs 0.5⩽ S post-exp. ⩽ 1,2, thus indicating a denser grouping of values around the mean, a certain alignment of indicators, which at the pre-experimental stage were characterized by a wider spread due to the heterogeneity of the contingent of students and their initial level of knowledge.

Conclusion

In the context of high expectations and requirements imposed on the lawyer by the modern labor market, the need for the introduction of practice-oriented methods of training becomes obvious. During the training of these specialists in a foreign language, which is essentially a tool for their future professional activity, such a question seems inevitable. It is no accident that we cited sources indicating the re-orientation of the educational process from the assimilation of knowledge regardless of the processes of professional interaction to the modelling of the professional context, which, in addition to the direct cognitive basis, includes other dimensions that describe this type of discourse (

The described textbook, which proved its efficiency during the experiment, can be used as one of the means of comprehensive reform of the educational process, since we have convincingly shown that the use of this technology would introduce inevitable changes in the process as a whole, from goal-setting to the final control activity, as well as assessment procedures. Even though the experiment showed a more significant increase in the knowledge component (which has traditionally been dominant), we still consider it necessary to note the significant positive changes in more complex components of “skills” (up to 20%). Let us suppose that the presence of such interactively oriented modules, developed in addition to the main textbook, taking into account the thematic planning and being applied with a certain frequency, will contribute to the further progressive development of the above competence.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses her gratitude to all the students who took part in the experiment, as well as the colleagues from Lobachevsky State University of Nizhny Novgorod for having granted the opportunity to conduct research at their university.

References

- Almazova, N.I., Baranova, T.A., & Khalyapina L.P. (2017). Pedagogicheskie podhody i modeli integrirovannogo obucheniya inostrannym yazykam i professional'nym disciplinam v zarubezhnoj i rossijskoj lingvodidaktike [Pedagogical approaches and models of integrated foreign languages and professional disciplines teaching in foreign and Russian linguodidactics]. Language and Culture, 39, 116-134. [Rus.]. doi: 10.17223/19996195/39/8

- Almazova, N.I., Eremin, Yu.V., & Rubtsova, A.V. (2016). Productive linguodidactic technology as an innovative approach to the problem of foreign language training efficiency in high school. Russian linguistic Bulletin, 3 (7), 50-54. doi: 10.18454/RULB.7.38

- American Bar Association. Section of Legal Education and Admission. (1992). Legal education and professional development. Report of the task force on law schools and the professional development: narrowing the gap. Retrieved from https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/misc/legal_education/2013_legal_education_and_professional_development_maccrate_report).authcheckdam.pdf

- Council of Europe. (2018). Common European Framework of references for languages: learning, teaching, assessment. Retrieved fromhttp://www.coe-int/lang-cefr

- De Gioia, M., & Marcon, M. (2016). Didactique du lexique de la médiation [Didactics of the mediation lexicon]. In D. Markey, & S. Kindt (Eds.) Didactique du français sur objectifs spécifiques. Nouvelles recherches, nouveaux modèles (pp. 115-128). Antwerpen: Garant. [in French].

- Lockwood, C. D. (2013). Improving learning in the law school classroom by encouraging students to form communities of practice. The Clinical Law Review, Forthcoming; NYLS Clinical Research Institute Paper. Retrieved from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2272062

- Pohjonen, S., & Lindblom‐Ylänne S. (2002). Challenges for teaching interaction skills for law students. The Law Teacher, 36:3, 294-306, doi: 10.1080/03069400.2002.9993110

- Porshneva, E.R, Abdulmianova I.R., & Zinovieva I.Y. (2016). Formirovanie kompetencii mezhkul'turnogo vzaimodejstviya [Forming the competence of cross-cultural interaction]. In N.V. Baryshnikov (Ed.) Traditions and novations in teaching foreign languages and cultures: harmonization or confrontation (pp. 16-22). Piatigorsk State Linguistic University. [in Rus.].

- Stuckey, R. (2007). Best practices for legal education. Retrieved from http://www.cleaweb.org/Resources/Documents/best_practices-full.pdf

- Tareva, E.G., Schepilova, A.V., & Tarev, B.V. (2017). Intercultural content of a foreign language textbooks: Concept, texts, practices. XLinguae, 10, 246-255, doi: 10.18355/XL.2017.10.03.20

- Tareva, E.G, & Tarev B.V. (2018). The assessment of students’ professional communicative competence: New challenges and possible solutions. XLinguae, 11(2), 758-767, doi: 10.18355/XL.2018.11.02.59

- The Carnegie foundation for the advancement of teaching. (2007). Educating lawyers. Preparation for the profession of law. Retrieved from http://archive.carnegiefoundation.org/pdfs/elibrary/elibrary_pdf_632.pdf

- Turner, J., Bone, A., & Ashton, J. (2016). Reasons why law students should have access to learning law through a skills-based approach. The Law Teacher, 52 (1), 1-16.

- Voskresenskaya, M. (2018). Sravnitel'nyj analiz uchebnikov francuzskogo yazyka dlya yuristov v Rossii i Francii: celi, struktura, soderzhanie [Comparative analysis of French for lawyers’ textbooks: objectives, structure, content]. In L.G. Vikulova & K.M. Ilinski (Eds.), Enseignement et apprentissage du français et du russe langues étrangères: parcours linguistiques et didactiques (pp. 43-49). Moscow: Yaziki narodov mira [in Rus.].

- Young, R.F. (2011). Interactional competence in language learning, teaching and testing. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 426-463). New York: Routledge

- Young, R.F. (2008). Language and interaction: An advanced resource book. London and New York: Routledge.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-050-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

51

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2014

Subjects

Communication studies, educational equipment,educational technology, computer-aided learning (CAL), science, technology

Cite this article as:

Voskresenskaya, M. (2018). The Textbook As A Tool To Form Sl Interactional Competence: Efficiency Study. In V. Chernyavskaya, & H. Kuße (Eds.), Professional Сulture of the Specialist of the Future, vol 51. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1447-1457). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.154