Abstract

Teachers' training is mostly imposed by the the need to accumulate a number of credits, the reforms in education or some dysfunctions in teaching activity. Continuing training, as its name suggests, should be seen as a long-term process and not as a set of disjointed events (courses and workshops). This change of paradigm implies the need for teachers to have at their disposal complex and up-to-date instruments necessary to training needs analysis and to monitoring their professional development. Based on these instruments they could be able: to assess their teaching skills and practices, to decide the most effective way to optimize their teaching (support from school, learning from practice and/or attending training course), to regulate and proof their professional development.

Keywords: Professional developmenttraininginquiryteaching

Introduction

The educational system is constantly a subject of revisions and innovations, driven by social evolution, pupils' needs, and the context of learning. These revisions should be related to the professional development of teachers, the latter being an important factor in the effective implementation of reforms at any level (Bell & Gilbert, 2015; Yigit & Bagceci, 2017: 243). Teachersʼs professional development is a concern for the students, parents, school institutions and governors (ibidem) because they can meet their needs and interests (James, Ashcroft, & Orr-Ewing, 2002: 128).

Numerous studies are devoted to professional training and development, and this is seen from the perspective of the teacher's effort to expand his professional skills and competences (Desimone, 2009: 182) and the efforts of institutions to provide the necessary training framework (Broad & Evans, 2006: 7). Professional development is sometimes assimilated with teachers learning and transfer of knowledge into practice (Avalos, 2011); with learning by action (Devetek & Vogrinc, 2014: 183); with its effects such as the creation of professional thinking and the development of learning to learn skills, critical reflection, development of emotional intelligence, etc. (Day, 1999 quoted by Rose & Reynolds, 2011).

In the literature field, professional development of teachers is defined as a three-dimensional (professional, individual and social) learning process that takes place throughout the professional life and aims at enriching knowledge and developing the skills and competencies needed to successfully fulfill professional roles. It is "the result of gaining increased experience and examining its systematic teaching" (Glatthorn, 1995 cited by Villegas-Reimers, 2003) and its goal is to increase the efficiency of learning activity and, implicitly, student performance.

In this long-term process, teachers integrate and transfer to the classroom the knowledge gained in the university, the experiential knowledge, the knowledge acquired in formal contexts (training, mentoring, workshop, demonstrative lessons offered by experienced colleges) and informal discussions with colleagues and school leadership, study of literature, documentary films, etc.) They develop different learning patterns (Vermont, 2014: 85) and, over time, make the transition from 'professional learners' to 'learning professionals' (Eraut, 2003: 14).

Grundy & Robison (2004: 154) emphasizes the importance of learning at work by showing that in classroom activity the teacher faces different situations and interactions that lead to the development of their professional knowledge and skills and their personal, social and emotional development. Therefore, the experience gained in teaching is the necessary filter for the selection of effective knowledge and practices and a tool for regulating vocational learning.

Díaz-Maggioli (2004: 13) prefigures some characteristics of successful professional development in response to the finding that often professional development has little positive effect on student learning. Thus, in order to be effective, professional development must involve collaborative decision-making, a growth-driven approach, tailor-made techniques, varied and timely delivery methods, adequate support systems, context-specific programs, proactive assessment, andragogic (adult-centered) instruction.

Grundy & Robison (2004: 153) points out that professional development cannot be determined by coercive measures but involves voluntary involvement.

Problem Statement

Frequently, teacher training institutions offer training / professional development programs elaborated on subjective considerations, without prior consultation of the trainees. In Romania this practice is all the more damaging as a number of teachers are involved in training activities. Most of them attend training programs because the current legislation obliges them to have 90 transferable credits for each five-years of teaching career, while the rest attend training programs for subjective reasons (to promote in a career, to run for a job etc.) At the same time, the teachers willing to self-assess their teaching activity and to identify their training needs do not have the necessary instruments. It is therefore necessary to provide instruments and information for the real needs of teacher training and development.

Research Questions

The question is: What are the training / professional development needs of the teachers involved in the survey? Needs analysis focused on: a) the knowledge and skills of designing, implementing and evaluating an effective teaching-learning process; b) the relationships with colleagues, parents and local community, and c) the professional development management.

Purpose of the Study

The present study was designed to identify the views of a sample of teachers from the northern region of Romania on their training / professional development needs. The results obtained through the survey can be used by trainers, teachers, school institutions, etc. and can contribute to improving the offer and quality of training programs dedicated to the development of teaching competences.

Research Methods

Data collecting and processing

The research presented in this study was conducted online, between January and May 2017. The instrument used included demographic data and 67 items structured in 10 areas: Job description, Relationship with students, Teaching - learning activity, Designing - Planning, Specialty knowledge, Evaluation and monitoring, communicating with colleagues, Communication with parents, Maintaining communication with the local community, Professional development management. The applied questionnaire was adapted and developed according to the instrument developed by Farla, Ciolan & Iucu (2007). Completion of the questionnaire was done on a 5-step Likert scale (total disagreement - total agreement). In addition, there were three debates with 23 teachers and school directors attending a master degree program.

Participants

The subjects involved in the research are 316 teachers from the North of Romania. Participation in the investigation was voluntary. Respondents are mostly women (80.01%) and come from rural (33.86%) and urban (66.14%) areas. 38.29% of respondents teach in high schools, 27.85% teach in secondary schools, 23.42% in primary school and only 10.44% in pre-primary. 61.71% of the respondents have all teaching degrees and 7.91% are executives/ school directors.

The analysis of the data in the table shows that the majority of the respondents are teachers who teach in secondary schools and high schools (66.14%) and have II or I teaching degree and doctorate (85.13%).

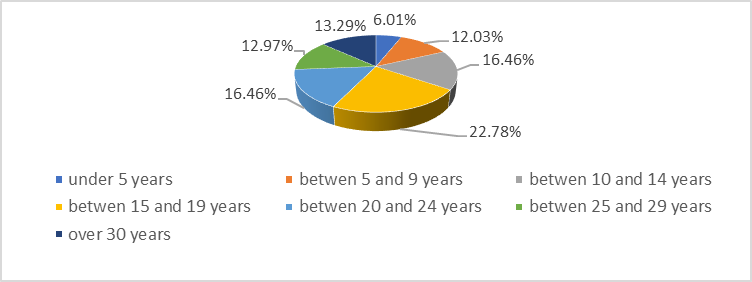

As shown in Figure

Research method

The research method is a type of opinion based research method.

Findings

Analysis of synthesis data

The results on item domains are presented in Table

Results by domain

The

The

The

The

The domain of

The domain of

The domain of

The domain of

The domain of

The domain of

Discussion

Respondents agree in a very large percentage of the claims that are made in the analysis of training needs, in particular with regard to items related to teaching-learning activity. We deduce that for the most part these competences do not represent training needs / professional development needs. This can be explained by the fact that 76.58% of respondents have high-level didactic degrees (first degree and doctoral studies), and great experience as teachers. Therefore, having such an educational background, they were also beneficiaries of numerous training programs.

Regarding the job sheet, the discussions with teachers and directors show that this is considered a mere formality, as the tasks mentioned in the document are often overcome numerically by the tasks that really belong to the teacher.

Communication with parents is deficient due to lack of time or lack of parental interest. For example, parents of pupils in rural areas work in agriculture or maintain a household alongside the job they have. As a result, they give little time to their relationship with school. Concerning the lack of parental interest, teachers show that it is necessary to educate parents in this regard.

Communication with the local community is often reduced to inviting community representatives to festivities (Day of Open Doors, end of school year, National Holidays, etc.) and to school visits to local institutions (police, town hall, church, etc.) In the opinion of the discussions group we cannot talk about systematic relations with the local community, about the real involvement of the community in school life and it is necessary to educate the school and the community in this respect.

The item with the lowest percentage of agreement in the field of Professional Development Management is "To fulfill other responsibilities in school, I would need more training in the field of my interest" (total disagreement: 4,43%; partial disagreement: 7.91%, indifferent: 16.14%, partial agreement: 24.68%, total agreement: 46.84%). The participants in the discussions group concluded that teachers are less interested in responsibilities other than those concerned with teaching, are not at all interested in unpaid responsibilities (e.g. in charge of vocational training) being more interested to get a managerial job.

The agreement-disagreement ratio has the highest values for the items "I set specific, measurable, realistic and achievable personal goals" (74.26) and "I am interested and involved in my own professional development" (59.89). In relation, these values refer to a constant and systematic concern for professional development. Referring to these results the participants in the discussion group stressed that teachers, particularly young teachers, are becoming aware of the competition in their profession and of the need to improve their knowledge and teaching skills. However, they mention "the hunting of diplomas and credits" showing that this extrinsic motivation replaces for some teachers the interest to develop their knowledge and skills.

Conclusion

The training programs offered by the various institutions (universities, teachers' houses, school inspectorates or ONGs) must be built on the real needs of teacher’s training, needs to be identified through in-depth training needs analysis.

Teachers interested in their professional development should be trained to use specific tools to assess their professional skills and identify their training needs. School directors and teachers must be educated to identify quality training programs that best meet professional needs and not encourage/prefer participation in training programs in order to obtain credits or diplomas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants involved in this survey.

References

- Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in Teaching and Teacher Education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education 27(1), pp.10-20.

- Bell, B., Gilbert, J. (2015). Teacher Development: A Model from Science Education. Washington DC/ London: Falmer Press.

- Broad, K., Evans, M. (2006). Review of Literature on Professional Development Content and Delivery Modes for Experienced Teachers. Ontario: University of Toronto, Ontario Ministry of Education.

- Desimone, L.M. (2009). Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures. Educational Researcher, 38 (3), pp. 181–199.

- Devetek, I., Vogrinc, J. (2014). A Profile Model of Science Teachers′ Professional Development, a Slovenian Perspective of Implementation of Action Research. 3.3. In: C. Bolte, J. Holbrook, R. Mamlok-Naaman & F. Rauch (eds.), Science teachers′ continuous professional development in Europe: Case Studies from the PROFILES Project (pp. 182-188). Berlin: Freie Universität.

- Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2004). Teacher-centered professional development. USA: ASCD.

- Eraut, M. (2003). Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. London/Philadephia: Falmer Press.

- Farla, T. (Ed.), Ciolan, L., Iucu, R. (2007). Analiza nevoilor de formare: ghid pentru pregătirea, implementarea şi interpretarea datelor analizei de nevoi de formare în şcoli. PHARE EuropeAid /121446/D/SV/RO: „Asistenţă tehnică pentru sprijinirea activităţii Centrului Naţional de Formare a Personalului din Învăţământul Preuniversitar“.Bucureşti: Atelier Didactic.

- Grundy, Sh., Robison, J. (2004). Teacher professional development: themes and trends in the recent Australian experience, Chapter 6. In: Christopher Day & Judyth Sachs (eds.), International Handbook on the Continuing Professional Development of Teachers (pp. 146-166). England: Open University Press.

- James, D., Ashcroft K., Orr-Ewing, M. (2002). The professional teacher (Chapter 7). Kate Ashcroft & David James (eds.). The creative professional: learning to teach 14–19-year-olds (pp.109/131). USA/Ca: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Lim, T.L.S. Teacher Professional Development through Action Research: The Case For A Mathematics. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 267996125_TEACHER_PROFESSIONAL_DEVELOPMENT_THROUGH_ACTION_RESEARCH_THE_CASE_FOR_A_MATHEMATICS_TEACHER [accessed Jul 6, 2017].

- Rose, J., Reynolds, D. (2007). Teachers’ Continuing Professional Development: A New Approach. 20th Annual World ICSEI, Available from: http://www.fm-kp.si/zalozba/ISBN/978-961-6573-65-8/219-240.pdf [accessed Jul 6, 2017].

- Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development. UNESCO: International Institute for Educational Planning. www.unesco.org/iiep [accessed July 6, 2017].

- Vermont, J. (2014). Teacher Learning and Professional Development. Sabine Krolak-Schwerdt, Sabine Glock & Matthias Böhmer (Eds.).Teachers’ Professional Development. Assessment, Training, and Learning (pp.79-85). Rotterdam/Boston/Taipei: Sense Publishers.

- Yigit, C. Bagceci, B. (2017). Teachers’ Opinions Regarding the Usage of Action Research in Professional Development. Journal of Education and Training Studies. 5(2), February, pp. 243-252.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 June 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-040-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

41

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-889

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Todoruț, G., & Ciascai, L. (2018). An Inquiry In Teachers Professional Development. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2017, vol 41. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 485-493). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.06.57