Abstract

The aim of the present paper was to examine the relationship between self-efficacy, burnout, and psychological well-being dimensions in a sample of Romanian teachers. The sample consisted of 217 school teachers, 197 females and 20 males, with ages ranged from 22 to 58. Results revealed positive lower correlations between teacher self-efficacy and the six psychological well-being dimensions. Teacher self-efficacy was significant and negatively correlated with exhaustion and depersonalization and positively correlated with personal achievement. Teachers with low and high level of psychological wellbeing dimensions significantly differ in their perceived self-efficacy and burnout components. Those who scored lower on autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance reported lower levels of perceived self-efficacy within the teaching profession. Also, teachers with lower scores of all psychological well-being dimensions reported higher level of exhaustion and depersonalization and had higher tendency of reduction their personal achievement and to demotivate facing to difficulties. The effect sizes were high. The findings and the limitations of the study were discussed.

Keywords: Burnoutself-efficacywell-beingteacherteaching career

Introduction

Different people react to stress and burnout differently. Teaching is generally considered a

stressful profession and some teachers are more affected by burnout feelings than others along their

teaching career. Maslach and Jackson (1981) defined burnout as a work-related stress, which is expressed

both physically and mentally, described by three distinct dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and loss of the sense of personal accomplishment. Exhaustion refers to chronic

emotional fatigue resulting from the different professional demands and responsibilities.

Depersonalization is described by indifferent and negative attitudes toward students, detachment in

relationships with students or colleagues, avoidance of social contacts, withdrawing into oneself.

Depersonalization is similar with cynicism and loss of empathy in interpersonal relationships in

professional contexts. Finally, personal achievement refers to the decreasing of personal effort to

accomplish things as an effect of demotivation. The reducing personal achievement is associated with

negative self-perceptions and feelings of unsuccessful and inadequate (Maslach & Jackson, 1981), and

leads to lack of efficiency in achieving work goals. Conversely, feelings of low personal achievement can

generate burnout.

Teacher burnout has examined by numerous empirical studies that have been carried out in with

the aim to investigate the individual and school organization variables associated with burnout and its

dimensions. Unless teachers could experience a great deal of burnout, most of them may cope efficiently

with such work-related stress because are sustained by the self-efficacy ability in their adaptive efforts

that are required to attain educational goals. The concept of self-efficacy was defined by Bandura (1977,

1997) as the people’s beliefs in their capabilities to produce desired effects by their own actions. Self-

efficacy beliefs are mediating between skills and actions. Teacher self-efficacy refers to particular

teachers’ beliefs in their own capabilities to efficiently perform various professional activities in

educational settings. Perceived self-efficacy influences teachers’ adequately functioning through

cognitive, affective, motivational and selection processes (Bandura, 1997). Previous studies explored the

relationship between teacher self-efficacy and teachers burnout (Brouwers, & Tomic, 2000; Evers, Tomic

& Brouwers, 2004; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2008; Schwarzer, & Hallum, 2008). Researchers found strong

relation between these variables (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007). Teachers with low level of self-efficacy

reported high degrees of burnout (Chwalisz, Altmaier, & Russell, 1992). Also, teacher self-efficacy

beliefs were negatively related to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization dimensions of burnout and

positively related to the personal accomplishment (Evers, Brouwers, & Tomic, 2002; Skaalvik &

Skaalvik, 2010). Similarly, teacher self-efficacy was examined as a predictor of teacher burnout

(Friedman & Farber, 1992; Savaş, Bozgeyik, & Eser, 2009; Bayani, Bagheri, &Bayani, 2013) and as

mediating construct between student behavior and burnout (Brouwers, & Tomic, 1999).

Psychological well-being is other variable that has been studied in relation to teacher burnout.

Teachers significantly contribute to the development of the students’ personality and their psychological

well-being is important from the perspective of teaching profession effectiveness in order to achieve the

educational goals. The concept of well-being generated a lot of scientific debates among researcher and

practitioner psychologists. Well-being is a dynamic concept that includes subjective, social, and

psychological dimensions as well as health-related behaviors. Ryff (1989) considered psychological well-

being as individual’s attempt to realize the own potential and conceptualized it as a multidimensional

construct consisting of six dimensions: autonomy (the sense of independence and self-determination in

thoughts and actions), environmental mastery (the sense of mastery and competence in managing the

environment, the control of external activities in order to obtain benefits of surrounding opportunities),

personal growth (the feeling of continued development, achieving the new experiences and realizing

individual abilities), positive relations with others (the feeling of empathy, affection, and intimacy in relations with others, the capacity to establish satisfying and trusting relationships with others), purpose

in life (having goals in life, a sense of directedness, and believing that there is meaning in the past and

present life), self-acceptance (positive attitude toward oneself and accepting the multiple aspects of self,

including good and bad qualities, having positive feeling about the past life) (Ryff, 1989; Ryff, 1995;

Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Review of scientific literature revealed that the study of well-being in teachers has

been focused especially on teacher subjective well-being and its psychological correlates and less on

psychological well-being aspects (Stanculescu, 2014). A number of studies examined the psychological

well-being in teachers and its relationships with individual and school organization variables have been

conducted (Damasio, Pimenteira de Melo, & Lustosa 2013; Refahi & al., 2015; Jantarapat, Suttharangsee,

& Petpichechian, 2014; McInerney & al., 2014).

Purpose of the Study

The present study aims to investigate the relationships between self-efficacy, burnout, and well-

being in a sample of Romanian teachers. The main objectives of the study are the following:

- To examine the relations between self-efficacy, burnout, and psychological well-being in

teachers;

- To identify differences in teachers’ self-efficacy and burnout depending on psychological well-

being.

Arising from these objectives, the following hypotheses were tested:

H1. Teacher self-efficacy is positively correlated with psychological well-being dimensions.

H2. Exhaustion and cynicism are negatively correlated with psychological well-being dimensions,

whereas personal achievement is positive correlated with psychological well-being dimensions.

H3. We presume differences in teacher self-efficacy depending on the level of psychological well-

being.

H4. We presume differences in teachers’ burnout depending on their psychological well-being.

Method

3.1.Participants

A total of 217 school teachers, 197 females and 20 females, with ages ranged from 22 to 58 (mean

age=31.00, SD=9.32) participated in the study. 45 of participants were preschool teachers, 86 primary

school teachers, and 86 secondary school teachers. Their teaching experience ranged from 1 to 34 years

(mean age=7.65, S =7.72). 144 participants are from urban and 73 from rural environment.

3.2.Measures

Participants completed three self-reported instruments.

the Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale (TSES) (Schwarzer, Schmitz, & Daytner, 1999). The scale consists of 10

items (e.g. “When I try really hard, I am able to reach even the most difficult students”; “I am confident in my ability to be responsive to my students‘ needs even if I am having a bad day”). Responses were

given on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (exactly true). The items are all positively

worded and direct in the content. The final score was calculated as medium score of the items. The

reliability of the scale measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .78.

Survey (MBI-ES), developed by Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter (1996). The instrument consists of 22 items

divided in three subscales. The dimensions of burnout are the emotional exhaustion, measured by nine

items, depersonalization, measured by five items, and the reduction of personal achievement consisted of

eight items. Participants rated their responses on a 7-point scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“every day”). The

results consist of three separate scores, one for each factor. The scores of the subscales were calculated as

mean scores of the items whereby each construct was measured. The overall score of the scale was

calculated as a combination of high scores on the first two subscales and a low score on the third subscale

that indicated high levels of burnout in teachers. Cronbach's alphas for the subscales were .75, .70, and

.81, respectively. The subscale for personal achievement is different from the other two sub-scales

because the scoring is reversed.

scale, developed by Carol Ryff (1989), consists of 6 dimensions: autonomy, environmental mastery,

personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. The short 42-item

version (Ryff, Keyes & Hughes, 2004), with 7 items for each subscale, was applied. Participants

indicated their degree of agreement to various statements on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1

(strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The scores of the subscales were calculated as mean scores of

the seven component items. Higher scores on each subscale indicated greater well-being on that

dimension. The Cronbach's alphas for the subscales were 0.71 (autonomy), 0.74 (environmental mastery),

0.77 (personal growth), 0.785 (positive relations), 0.79 (purpose in life), and 0.805 (self-acceptance),

respectively.

Participants with missing data on applied scales were removed from the sample. Participants

received course credits for their participation.

Results

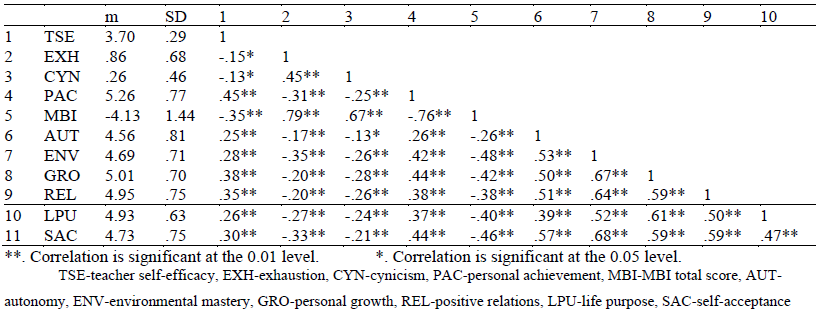

Means and standard deviations for all measures were calculated. Pearson correlation coefficients

were computed to examine the associations between variables. Descriptive statistics and correlations

between variables are presented in Table

As can be seen in Table

between teacher self-efficacy and all six psychological well-being dimensions. Significant negative low

and medium correlations were obtained between exhaustion and all six psychological well-being

dimensions. Also, cynicism and psychological well-being components have lower negative associations.

Personal achievement was positive correlated with all psychological well-being dimensions. The

teachers’ overall score on MBI is negatively medium correlated with participants’ score on TSE scale (r=-

.35). Correlations between the MBI and its subscales are high: .79 (MBI and burnout subscale), .67 (MBI

and cynicism subscale), - .76 (MBI and personal accomplishment subscale). Moreover, the teachers’

mean score on exhaustion subscale was .86 (SD = .68) indicating a relative moderate degree of emotional

exhaustion. The overall mean score on cynicism subscale was .26 (SD= .46) indicating a moderate to high

degree of depersonalization. The teachers’ overall mean score on personal accomplishment subscale was

5.26 (SD= 5.37) indicating a moderate degree of personal achievement.

Concerning the second hypothesis, based on the means on each psychological well-being subscale,

the sample was divided in two subgroups: with low and high level on that psychological well-being

dimension, respectively. To assess differences in teachers’ self-efficacy and burnout depending on the

level of psychological well-being, independent t-test was applied. r2 coefficient of determination as

indicator of effect size was calculated.

As can be seen in Table 2, results revealed significant differences in teacher self-efficacy (m1-m2=

-.12, p< .01, r2= .04), burnout (m1-m2= .32, p< .01, r2= .05), depersonalization (m1-m2= .14, p< .05, r2=

.02), personal achievement (m1-m2= -.31, p< .01, r2= .04), and the MBI total score (m1-m2= .77, p< .001,

r2= .07) between teachers with low (N1=108) and high autonomy (N2=109).

Also, teachers with low (N1=104) level of environment mastery differed from those with high

level (N2=113) in their perceived self-efficacy (m1-m2= -.12, p< .01, r2= .04), burnout (m1-m2= .27, p<

.01, r2= .04), depersonalization (m1-m2= .17, p< .01, r2= .04), personal achievement (m1-m2= -.51, p<

.001, r2= .13), and their MBI total score (m1-m2= .96, p< .001, r2= .13).

Concerning personal growth as dimension on psychological well-being, teachers with low

(N1=108) level differed from those with high level (N2=109) in the perceived self-efficacy (m1-m2= -.14,

p< .001, r2= .06), burnout (m1-m2= .24, p< .01, r2= .04), depersonalization (m1-m2= .22, p< .001, r2= .06), personal achievement (m1-m2= - .49, p< .001, r2= .11), and MBI total score (m1-m2= .96, p< .001, r2= .12).

Teachers with low (N1=100) positive relations with others reported different scores from those

with high positive relations (N2=117) in their perceived self-efficacy (m1-m2= -1.67, p< .001, r2= .08),

burnout (m1-m2= .30, p< .01, r2= .04), depersonalization (m1-m2= .25, p< .001, r2= .07), personal

achievement (m1-m2= -.47, p< .001, r2= .11), and their MBI total score (m1-m2= 1.03, p< .001, r2= .14). Similarly, teachers with low (N1=108) purpose of life differed from those with high life purpose

(N2=109) in their perceived self-efficacy (m1-m2= -.12, p< .01, r2= .05), burnout (m1-m2= .27, p< .01, r2=

.04), depersonalization (m1-m2= .18, p< .01, r2= . 04), personal achievement (m1-m2= -.46, p< .001, r2=

.10), and their MBI total score (m1-m2= .92, p< .001, r2= .12).

Finally, teachers with low (N1=109) and high (N2=108) self-acceptance reported different levels of

perceived self-efficacy (m1-m2= -.16, p< .001, r2= .09), burnout (m1-m2= .40, p< .001, r2= .09),

depersonalization (m1-m2= .19, p< .01, r2= .04), personal achievement (m1-m2= -.51, p< .001, r2= .12),

and their MBI total score (m1-m2= 1.11, p< .001, r2= .16).

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationships between self-efficacy, burnout, and well-being in a

sample of Romanian teachers. First, we calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficients to examine the internal

consistencies of the used scales. All scales and subscales yielded acceptable internal consistencies, ranged

from .70 (depersonalization-MBI) to .81 (personal achievement –MBI, self-acceptance- PWBS).

Results revealed that teacher self-efficacy is positively correlated with all six psychological well-being

dimensions. Teacher self-efficacy was lowest correlated with autonomy and relatively medium correlated

with personal growth and positive relations with others dimensions. Also, exhaustion and cynicism

components are negatively associated with psychological well-being dimensions, whereas personal

achievement has positive medium correlations with psychological well-being dimensions.

Concerning the relationships between self-efficacy and burnout components the findings has shown

negative significant correlations with exhaustion and depersonalization and positive significant

correlations with personal achievement. Thus, teachers with higher skills within the teaching profession

might be characterized of lower levels of stress or symptoms of burnout and depersonalization or

cynicism in interpersonal relations. These efficient teachers show to their students and/or colleagues

more negative attitudes and professional empathy. Teachers who scored high on the entire MBI reported

low levels of psychological well-being in each subscales, and conversely. The first our two hypotheses

were supported.

In order to identify the differences between teachers with different job skills within the teaching

profession

significantly differ than those with high psychological well-being in their perceived self-efficacy. Those

with lower scores on autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others,

purpose in life, and self-acceptance have lower perceived self-efficacy within the teaching profession.

The effect sizes were medium and high. Also, were obtained differences in the level of teachers’ burnout depending on their psychological well-being as follows: teachers with lower autonomy, environmental

mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance have higher

level of exhaustion, and conversely. The effect sizes were medium. Similarly, teachers with lower

autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and

self-acceptance have higher level of depersonalization, and conversely. In other words, teachers who are

higher self-determining and independent, possess a positive attitude toward the self, have satisfying

relationships with others, goals in life, feelings of continued development and competence in managing

the environment have significant lower levels of burnout and depersonalization than those with low

autonomy and ability to develop new attitudes or behaviors, negative attitude toward the self, few goals or

aims, difficulties in managing the environment and unsatisfied relationships with others.

With regard to the third component of burnout - personal accomplishment, our findings revealed that

teachers with high well-being significantly differ than teachers with low psychological well-being. By

comparison, teachers with lower autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations

with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance have higher tendency of reduction of their personal

achievement and to demotivate facing to difficulties. The effect sizes were high in all cases. The last two

hypotheses were supported.

Conclusions

The current study examined the relationship between teacher self-efficacy, teacher burnout and

teacher’s well-being in a Romanian sample. We found that teacher self-efficacy significantly related to

teacher burnout and well-being dimensions, which is consistent with the previous studies.

This study has certain limitations. First, the findings are limited by the characteristics of the sample.

All participants were teachers with different specializations but on the same south-east region of the

country. Therefore, our findings cannot be generalized over all Romanian teachers. The second limitation

refers to the instruments we used. The internal consistencies of the used scales and their subscales have

acceptable or good internal consistencies but not high. The third limitation refers to the fact that present

study focused on the relationships between few variables which have been already examined as relevant

for teacher personality and teaching profession, consequently, the perspective of the study is simply

descriptive. For these reasons, the findings of the present study are only a starting point for next

prospective research focused on understanding teacher personality in the context of professional demands

and responsibilities. On the basis of these results, could be testing explanative models of teacher burnout

based on various variables relative to self. Secondly, findings of this study could provide possible

directions to action against teacher burnout by prevention and intervention programs focused

simultaneously on increasing teacher self-efficacy ability and psychological well-being.

References

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change.. Psychological Review

- (), 84, 191-215.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control

- Bayani, A. A.Bagheri, H.Bayani, A. (2013). Teacher self-esteem, self-efficacy and perception of school context as predictors of professional burnout.. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences, 2(2), 298-304

- Brouwers, A.Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management.. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 239-253

- Chwalisz, K.Altmaier, E. M.Russell, D. W. (1992). Causal attributions, self-efficacy cognitions, and coping with stress.. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 11(4), 377-400

- Damásio, B. F.Pimenteira de Melo, R. L.Lustosa, R. (2013). Meaning in Life, Psychological Well-Being and Quality of Life in Teachers.. Paidéia, 23(54), 73-82

- Evers, W. J.Tomic, W.Brouwers, A. (2004). Burnout among teachers: Students’ and teachers’ perceptions compared.. School Psychology International, 25(2), 131-148

- Evers, W. J.Brouwers, A.Tomic, W. (2002). Burnout and self-efficacy: A stud y on teacher s’beliefs when implementing an innovative educational system in the Netherlands.. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 227-243

- Friedman, I. A.Farber, B. A. (1992). Professional self-concept as a predictor of teacher burnout.. Journal of Educational Research, 86, 28-35

- Jantarapat, C.Suttharangsee, W.Petpichechian, W. (2014). Factors related to psychological well-being of teachers residing in a situation of unrest in Southern Thailand.. Songklanagarind Journal of Nursing, 34, 76-85

- Maslach, C.Jackson, S. E. (1981). MBI: Maslach burnout inventory.. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press

- Maslach, C.Jackson, S. E.Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd

- (), Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- (), ed.). Palo

- McInerney, D. M.Ganotice, F. A.Morin, A. J. (2014). Teachers’ Commitment and Psychological Well-being: Implications of self-beliefs for teaching in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology,.. doi, 35(8), 926-945

- Refahi, Z.Bahmani, B.Nayeri, A.Nayeri, R. (2015). The relationship between attachment to God and identity styles with Psychological well-being in married teachers.. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 1922-1927

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological wellbeing.. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 57, 1069-1081

- Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life.. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 99-104

- Ryff, C. D.Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited.. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719-727

- Ryff, C. D.Keyes, C. L. M.Hughes, D. L.Brim, O. G.Ryff, C. D.Kessler, R. C. (2004). Psychological well-being in MIDUS: Profiles of ethnic/racial diversity and life-course uniformity. . How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife - 422).. Chicago, 398-

- Savaş, A. C.Bozgeyik, Y.Eser, I. (2009). A Study on the Relationship between Teacher Self Efficacy and Burnout.. European Journal of Educational Research, 3(4), 159-166

- Schwarzer, R.Schmitz, G. S.Daytner, G. T. (1999). Teacher Self-Efficacy.. Retrieved from, http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/teacher_se.htm

- Skaalvik, E. M.Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout.. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 611-625

- Skaalvik, E. M.Skaalvik, S.Craven, R.Marsh, H. W.McInerney, D. (2008). Teacher self-efficacy: conceptual analysis and relations with teacher burnout and perceived school context

- (), Self-processes, learning, and enabling human potential (pp. 223-247). Connecticut: Information Age Publishing.

- Skaalvik, E. M.Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations.. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059-1069

- Corresponding Author: Cristina - Corina Bentea Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference eISSN: 2357-1330 Schwarzer , R.Hallum , S. (2008). Perceived teacher self-efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: mediation analys(Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 152-171. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00359.x. Stanculescu, E. (2014). Psychological predictors and mediators of subjective well-being in a sample of Romanian teachers. Revista de cercetare si interventie sociala, 46, 37-52. 1136)

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 May 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-022-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

23

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2032

Subjects

Educational strategies, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Bentea, C. -. C. (2017). Teacher Self-Efficacy, Teacher Burnout And Psychological Well-Being. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 23. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1128-1135). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.139