Abstract

The contribution deals with possibilities of development of social skills with pre-school children by means of physical activities. We work on the presumption that physical activities are a rich source of emotions and situations with a strong hub, so they provide considerable scope for developing social skills in a playful and entertaining way. The contribution presents running results of the pedagogical experiment, which was aimed at testing the program of physical activities aimed at developing social skills in children. Running results suggest that well-chosen physical activities lead to development of social skills in children, particularly regarding respecting rules, regulation of emotions and the ability to cooperate. The text is an outcome of the IGA project run on Tomas Bata University in Zlín called Support of Social Relationships in Children’s Groups by Means of Physical Activities (IGA/FHS/2015/010).

Keywords: Social relationshipschildren’s groupsphysical activities

Introduction

A children’s group in a kindergarten is an environment, where the child spends up to 9 hours a day. The social relationships among children can significantly influence a child’s personality; negatively perceived social relationships, ostracization or putting the child in a role of a “clown of the class” presents for him/her a very unpleasant experience causing strongly negative emotions. These can manifest not only in relationships to other children in the class – enemies, but also in the quality of their life, their contentment at school, self-evaluation. The care of social environment in a class and children’s groups in kindergarten seems to be an essential part of the work of educators. However, teachers hardly find space to integrate such focused activities while watching all other areas of a child’s development at the same time. Present experience and interviews with educators suggest their insufficient theoretical and practical facilities for effective development of children’s social skills. It is thus purposeful to look for such ways of developing a child’s personality (meaning also their social aspect), which can be naturally integrated into the common program of a class without placing high demands on teachers’ preparation and time needed for carrying out these efforts.

Development of a child’s social skills and support of social relationships in a peer group are anchored in the fundamental document – General Education Program for Preschool Education (Smolíková, Opravilová, Havlínová, Aleice & Krejčová, 2004). Although personality development and social relationships development weaves through practically all education areas of the General Education Program for Preschool Education (henceforth GEP PE), two out of five areas of the GEP PE are focused specifically on these issues: Child and the others, Child and society. Although the number of children does not correspond with the definition of a school class as a small social group (cf. Hrabal, 2003, Nekonečný, 2009, Výrost, Slaměník, 2008, Řezáč, 1998), other characteristics are fully in accordance with this interpretation. A school class is a group, which meets on daily basis. The children are in regular direct (unmediated) contact, there are reciprocal and many times very dynamic interactions. In the common day schedule in a kindergarten, there are many opportunities for a child’s social skills development. It thus concerns children’s free play and controlled activities, eating, time for resting, outdoor activities, etc. Motoric activities and games represent a specific means of children’s social skills development.

Problem statement

The key term of our text is social skills. They can be defined as

Along with social skills, we can come across the term

In this text, however, we focus primarily on specific acquired processes, not on their creative use. Henceforth, we will work with the term “social skills”.

It is already in the pre-school age, when the aimed and systematic development of basic social skills of a child takes place. Some skills stem from general social rules. A greeting, a request or a thank you should be a common part of the child’s behavior before beginning elementary school. However, it is necessary to develop other areas of the child’s behavior as well. Bednářová and Šmardová (2011) include namely:

communication (verbal and nonverbal)

adequate reaction to new situations

adapting to new environment

understanding their own feelings and self-control

understanding emotions and other people’s behavior

objective self-perception and self-evaluation.

Social skills are an integral part of preparedness of a child for school attendance. Goleman (2006) states seven most important aspects of the skill of learning, which he considers the basis of preparedness for school. They are:

self-confidence

curiosity

ability to act with purpose

self-control

ability to work with others

ability to communicate

ability to co-operate

From the above points it is clear that there is a close relationship between school preparedness and abilities of a child to function in a society. Sufficient level of social skills enables the child to focus his/her behavior on a certain goal and follow it (it supports attention). Schoolwork, however, is carried out in a group of peers. The child gets into interactions with peers and educator, has to not only communicate, but also establish, maintain and develop co-operation.

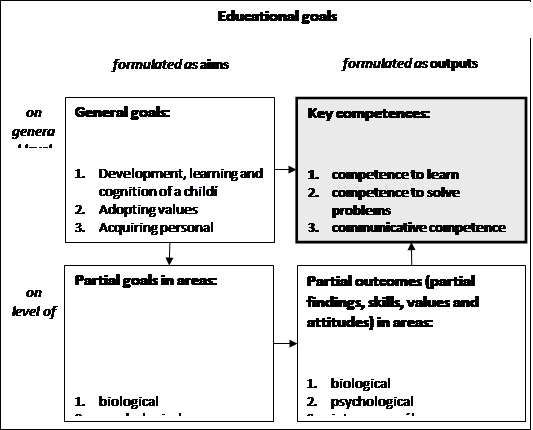

A kindergarten teacher significantly contributes to adequate level of the child’s preparedness for school not only in the area of practical skills and knowledge; it also creates internal conditions, which make the process of learning easier for the child. Therefore it is very necessary to pay enough attention to the development of social skills with pre-school aged children. As shown in Figure

Although the work of an educator in pre-school education and richness and variety of educational goals are significant, we believe the environment in kindergarten and organization of children’s life in it offers enough space for systematic development of social skills of children. The experience of educators and many experts show that for effective influence on the child’s social area, it is not enough to do a one-time exercise or a block of activities (cf. Gillernová, Krejčová, Horáková Hoskovcová, Šírová & Štětovská, 2012, Hermochová, 2005, Hermochová & Vaňková, 2014, Mohauptová, 2009). The optimal seems to be regular short-lasting meetings. Gillernová, Krejčová, Horáková Hoskovcová, Šírová & Štětovská (2012) see the main advantage in long-term administering and in the ability to gradually apply the newly-developed skills into real social situations. The essential condition of a successful training of social skills is the feeling of psychological safety. Meeting this condition enables the participants to be sufficiently open and honest. We see great risk in this condition in a children’s group. A pre-school aged child is naturally honest and is not able to think through the impact of his/her behavior. That is why some of children’s utterances and reactions to others may seem harsh and may produce worries from an open, honest behavior in others. Therefore, we believe it is suitable to use the form of a game which, in its characteristics, supports spontaneity and natural behavior in children.

In our work we leaned towards motoric games. We proceed from a supposition that the concept of motoric activities offers enough possibilities for developing social skills of a child and building a healthy social group in the class. They are usually in the form of a game, and are therefore attractive and entertaining for a small child. Motivation is multiplied also by unusuallness of the activities, new aids, which the child can work with and which revive common sporting-focused activities.

Game activities and non-traditional aids (tools and equipment) endorse the spontaneity in children, which gives room for natural behavior and unforced experiencing of joy of motion, but also a variety of different emotions induced by the motoric activities. Thus the child gets a chance to get to know his/her own emotions and reactions, get oriented in them and make work with own experiencing more effective. Orientation in themselves is then the essential foundation for getting to know and understanding others. “Most motoric activities and games consist in playing together, that’s why the expected outcomes formulated in the interpersonal area can be carried out in them” (Dvořáková, 2011, p. 24). At the same time, motoric activities are considerably variable in their demands for space, time and material conditions. Therefore we believe that it is possible to integrate them very naturally and without great time or other demands into suitable parts of pedagogical work, such as sporting and outdoor activities, physical education subjects, et al.

We think that namely activities from the area of psychomotor games offer an array of themes for children’s social skills development in kindergarten. Psychomotor activity as a system of motoric activities focused on experience (Blahutková, 2003) is an optimal means to utilize motion and induced emotions for deeper self-knowledge, but also managing intense emotions, desires and various conflicts among children. Adamírová (2006) defines psychomotor activity as responsible education through motion. A child in natural conditions penetrates deeper into his experiences, tendencies and usual reactions, and learns to handle them. They also learn about reactions of others, which provides them with valuable feedback in the relationship to his/her behavior. It is also the conditions of devising the psychomotor activities, stated by Zimmer, which create suitable psychosocial environment for developing social skills. According to Zimmer (2012), a child should primarily:

experience him/herself as an actor of the process

know how to relate success and failure to his/her person

create own measures of values and focus on them his/her own behavior

take responsibility for own actions

learn about alternatives of interruptive ways of behavior and integrate them into his/her own behavior

In order to fulfill these goals, it is possible to use various aids, tools and equipment, e.g. psychomotor parachute, paddle boat, balance platform, skipping rope, ropes, cones etc., through using of which the children give each other basic help. Through it, they learn to sense others with the means of verbal and nonverbal communication, developing empathy, own responsibility and they build a relationship of mutual trust. Aside from individual use (or use in pairs), these aids provide an array of group activities. In some cases it is financially demanding equipment, which a common kindergarten can afford only in rare cases. The system of psychomotor activities offers a rich scale of activities and games with objects commonly available (balls, skipping ropes, building sets with big bricks, benches et al.), objects of common use (PET bottles caps, yogurt cups, clothe pins), or completely without aids. In this way, these activities become easily available to all kindergartens.

Research questions

In the first half of 2016, we carried out a pedagogical experiment, which should disclose the answer to the main research question: How physical activities contribute to the development of social skills of preschool children?

Purpose of the study

The main goal of the project is to check on possibilities of using specific motoric activities from the area of psychomotor activities in the support of development of desirable social relationships in a school class and building a healthy social group in a school class group.

A partial goal is to suggest suitable motoric activities for building social relationships in children’s groups and providing support to teachers in the form of a publication focused on using motoric activities to develop personality and forming of a child’s social relationships.

Research methods

The pedagogical experiment was carried out between January – June 2016. The experimental and control group consisted of children from Zlín kindergarten 5 – 6 years of age. The advantage was that all the children attended the same kindergarten and are thus exposed to very similar external conditions. All children went through an initial and final examination, which included an individual interview, structured non-participating observation, drawing of a figure and a projective test CATO.

The interview was focused on the social aspects of the class, which the child attended, in a way perceived by the child him/herself.

The drawing of the figure is used for diagnosing mental maturity of the child. In our research though, we didn’t evaluate the level of rendition of the figure, but it served as an indicative assessment of the child’s relationship to him/herself. The induced identification of the child with the drawn figure later made the work with the CATO test easier.

CATO is a projective test which, by means of stimulus cards with pictures of non-specific social situations, projects the child’s social relationships within their family and outside of it. We focused primarily on the child’s relationships to their peers and an adult authority.

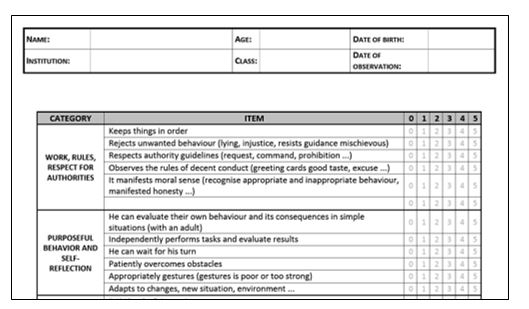

To review the level of specific social skills, we’ve put together a record keeping sheet of structured observation (Fig. 2). We aimed the observation on the following areas:

Work, rules, respect for authorities

Purposeful behavior and self-reflection

Regulation of emotions

Communication

Openness to people

Peer relationships

Cooperation

Every area is filled with 5 – 6 partial items evaluated on a scale 0 (= does not occur at all, does not manage) – 5 (occurs commonly, manages without problems).

Between the initial and final examination, the experiment group took part in an intervention program of motoric activities primarily from the area of psychomotor activities aimed at the social skill development. When putting together the program, our goal was to utilize mainly those activities, which can be easily integrated in a common day in a kindergarten, and which are not financially demanding. The program consisted of 12 lessons of 90 minutes.

Findings

Currently, the gained data is being evaluated by means of statistical methods, as well as thorough content analyses of interviews and data gained through the CATO test. In this text, we present only running results gained from records of observations with the experimental group. In other steps, we will assess the ascertained differences from the perspective of statistic significance of these changes and their comparison with the control group. The data will also be subject to more thorough analysis by individual items.

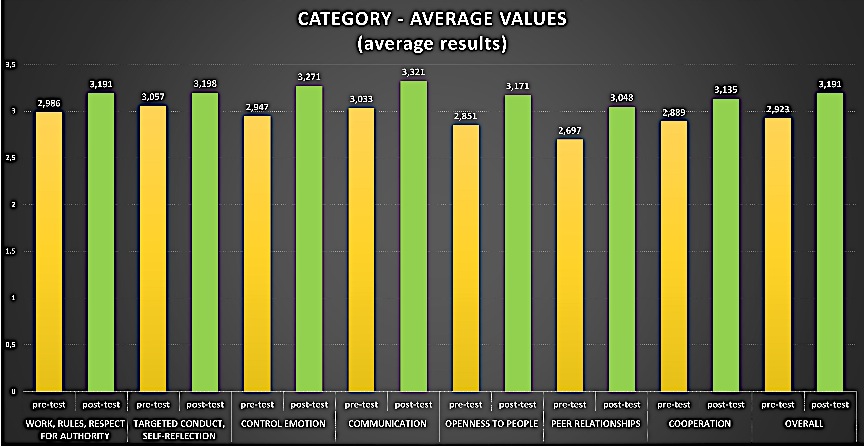

Figure

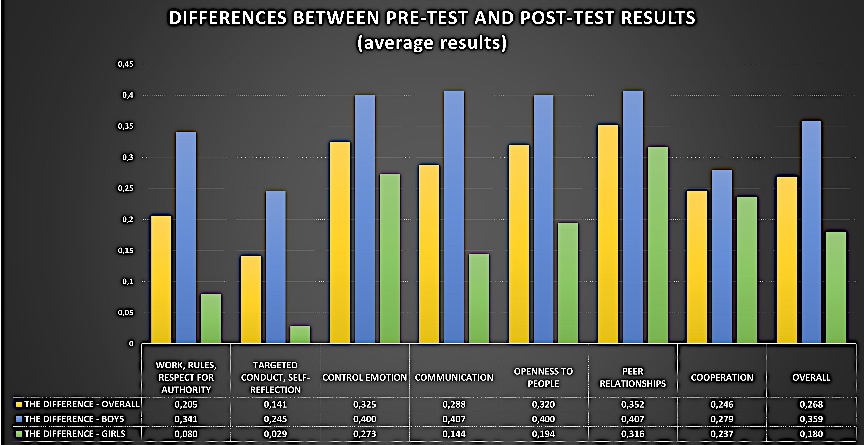

Further on, we observed differences between boys and girls. In Figure

In table

Conclusions

The work presents running results of a pedagogical experiment, whose aim was to verify the program of motoric activities focused on social skills development in pre-school aged children. The program consisted of 12 lessons consisting primarily of psychomotor activities. The initial and final examination consisted of individual interview, structured non-participating observation, drawing of a figure and a projective CATO test.

The partial results suggest that well-chosen motoric activities from the area of psychomotor activities lead to development of social skills in pre-school aged children, namely in the area of respecting rules, regulation of own emotions and the ability to co-operate with other children.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the staff in the kindergarten for the opportunity to carry out our research, for their willingness to actively take part and their patience with initial organization difficulties. We thank also parents of children for their approval of their children’s participation in the research examination. But most of all, we thank all the children for their enthusiasm and joy, with which they actively and spontaneously got involved in all games and activities.

References

- Adamírová, J. (2006). Hravá a zábavná výchova pohybem: Základy psychomotoriky. Praha: Komise zdravotní tělesné výchovy MR ČASPV.

- Bednářová, J., & Šmardová, V. (2011). Diagnostika dítěte předškolního věku: Co by dítě mělo umět ve věku od 3 do 6 let. Brno: Computer Press, a.s.

- Blahutková, M. (2003). Psychomotorika. Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

- Cook, C. R., Gresham, F. M., Kern, L., Barreras, R. B., Thornton, S., & Crews, S. D. (2008). Social Skills Training for Secondary Students With Emotional and/or Behavioral Disorders: A Review and Analysis of the Meta-Analytic Literature. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 16(3), stránky 131-144.

- Dvořáková, H. (2011). Pohybové činnoti v předškolním vzdělávání. Praha: Raabe.

- Gillernová, I., Krejčová, L., Horáková Hoskovcová, S., Šírová, E., & Štětovská, I. (2012). Sociální dovednosti ve škole. Praha: Grada Publishing.

- Goleman, D. (2006). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

- Hartl, P., & Hartlová, H. (2010). Velký psychologický slovník. Praha: Portál.

- Hermochová, S. (2005). Skupinová dynamika ve školní třídě (Dokážu to?. vyd.). Kladno: AISIS.

- Hermochová, S. (2006). Teambuilding (Vedení lidí v praxi. vyd.). Praha: Grada.

- Hermochová, S., & Vaňková, J. (2014). Hry pro rozvoj skupinové spolupráce. Praha: Portál.

- Hrabal, V. (2003). Sociální psychologie pro učitele: vybraná témata. Praha: Karolinum.

- Matsumoto, D. (Editor). (2009). The Cambridge dictionary of psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mohauptová, E. (2009). Teambuilding : cesta k efektivní spolupráci. Praha: Portál.

- Nakonečný, M. (2009). Sociální psychologie. Praha: Academia.

- Průcha, J., Walterová, E., & Mareš, J. (2013). Pedagogický slovník (7., aktualiz. a rozš. vyd.. vyd.). Praha: Portál.

- Řezáč, J. (1998). Sociální psychologie. Brno: Paido.

- Smolíková, K., Opravilová, E., Havlínová, M., Aleice, B., & Krejčová, V. (2004). Rámcový vzdělávací program pro předškolní vzdělávání. 48. Praha: Výzkumný ústav pedagogický. Načteno z http://www.vuppraha.cz/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/RVP_PV-2004.pdf

- Výrost, J., & Slaměník, I. (2008). Sociální psychologie (2., přepracované a rozšířené vydání. vyd.). Praha: Grada Publishing, a.s.

- Zimmer, R. (2012). Handbuch Psychomotorik: Theorie und Praxis der psychomotorischen Förderung. Freiburg: Herder.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-015-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

16

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-919

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Pacholíka, V., & Nedělová, M. (2016). Support of Social Relationships in Children’s Groups by means of Physical Activities. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 448-457). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.46