Abstract

Using a Household Income Survey (HIS), this study examines the private returns to education in Malaysian financial sector. First, we estimate the private returns to education using the highest certificate qualification or “sheepskin effects". Secondly, we analyse the trend of private returns to education during the years 2002–2007. Thirdly, we examine the effects of educational mismatch on private returns to education. The simple Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimator with robust standard errors is employed to estimate the earnings function. Our results indicate the presence of an over-education situation among degree-educated workers despite enjoying higher private returns. Such over-qualification in the financial sector is due to the mismatches in the supply of degree-educated workers for medium-skilled positions, which is now outstripping the supply of high-skilled workers. Interestingly, our results are found to contradict most of the previous empirical studies. Hence, our study is believed to contribute to the literature by explaining the phenomenon of over-education using the signalling hypothesis. Since over-education reflects inefficiencies in the allocation of resources, Institutes of Higher Learning (IHL) need to increase their interaction with industry in order to find a solution to the incidence of mismatch which is partly due to the lack of integration between education providers and employers in the demand driven labour market.

Keywords: Private returns to educationearningscertificates of qualificationover-education

Introduction

Investment in education is found to continue to be a very attractive investment opportunity nowadays. It is generally known that investment in education increases workers’ productivity by imparting useful knowledge and skills (Becker, 1964). Consistent with human capital and screening/signalling theories, myriad recent studies on returns to education show that credentialed workers(those with high school diplomas or college degrees) earn more than their non-credentialed counterparts (Beblavy,Teteryatnikova&Thum,2013;Cellini &Chaudhary,2014;Liu, Belfield & Trimble,2015 ).

As higher levels of educational attainment are strongly associated with higher employment rates and perceived as a gateway to better job opportunities and earnings, the Malaysian government has taken measures to increase the enrolment rate in tertiary education. According to 2011-2012 National Educational Statistics by the Ministry of Education (MoE), the enrolment percentage in the tertiary education increased by 41.41 per cent between 2006 and 2011 (EPU, 2010). This has resulted in an upsurge in the number of graduates, which in turn, increased the demand for higher-educated workers. At the macro level, the number of labour with higher education has increased sharply in the recent years. It increased markedly by about 70 per cent from 30,732 in 2000 to 51,771 in 2005, and continued to increase by nearly 25 per cent in 2012. Thus, the unemployment rate among graduates declined from 3.8 per cent in 2005 to 3.1 per cent in 2012 (EPU, 2010); However, comparing the increase in the supply of highly educated workers and the demand for such workers in Malaysia within the last decades, the question arises whether the increase in the demand for higher-educated labour has kept in pace with the increase in the supply of the workers. If the growth in the supply of higher educated workers outpaces the growth of its demand, over-educated labour is the likely result. Workers are over-educated if the skills they bring to their job exceed the skills required for that particular job. Another concern that arises is whether education is a worthwhile investment, considering the current employment paradigm (According to the 2011 Graduate Tracer Study (GTS)conducted by Ministry of Education, 27% of graduates from HEIs were still unemployed one year after graduation. This percentage went up to 28% for private HEIs and down to 17% among community College graduates. More than half of graduates with diploma holders especially in the technical areas jobless for nearly nine months each year after their graduation.) . Hence, the information on the returns to education can act as a useful indicator of the education productivity and provide incentive for individuals to invest in their own human capital.

Problem Statement

The economic literature faces long-lasting debate on the causes of the positive relationship between schooling and earnings. The theory of human capital is concern with the role of learning in determining the returns to education. This assumption prevails largely due to its success to describe the relationship between schooling and earnings in the earnings function (Psacharopoulos & Patrinos, 2004). On the other hand, screening theories of education, while allowing for learning, suggest that better educated individuals earn more because education serves as a credential which signals higher productivity (Spence, 1973; Arrow, 1973; Weiss, 1995).

Nonetheless, it is important to note the complexity to formulate the exact tests that are capable to discriminate between the human capital and the signal theories of education. One way to evaluate the screening theory of education is by testing whether individuals who receive qualifications earn more than their counterparts with the same number of years of education but do not hold any qualification. This is known in the literature as the “sheepskin effect (The empirical labour literature often refers returns to specific credentials of education as sheepskin effects. Sheepskin effects refer to the independent effect that certificates of qualification appear to have even after controlling for years of education. The estimation based on the highest level of schooling completed (credentials) is more accurate, because it provides an alternative structure for recovering the returns to schooling (Harmon, Oosterbeek, & Walker, 2003).) ”. In fact, most empirical research on earnings functions assume the absence of sheepskin effects (e.g: Hungerford & Solon,1987; Heywood,1994; Park,1999; Antelius, 2000; Trostel, 2005).

Malaysia is no different in this phenomenon since the relationship between certificates qualification and earnings is not very substantial (Hungerford & Solon,1987; Heywood,1994; Park,1999; Antelius, 2000; Trostel, 2005).The issue of unwillingness to pay salary based on the workers’ level of education in the economy sector has become an issue of current interest. This is particularly important because there are on-going concerns among employers about the skills provided by the Malaysian education system (EPU & Bank, 2012). At present, the Malaysian labour market faces two major problems. First is the problem of stagnant returns to education compared to the increasing level of certificates qualification or sheepskin effects. This shows that there is a non- linear relationship between earnings and level of certificates qualification. Second is the problem relating to declining returns to education for those with degree qualification. Both of these problems are evidences of the apparent fall in the returns to education, particularly for new graduates, specifically those who fail to secure graduate-level jobs (EPU & Bank, 2012). This raises the question as to whether there are educational mismatches (over and under-educated) amongst workers with degree qualifications (Over-education/over-qualification refers to the situation in which individuals are employed in jobs that do not require their current qualifications or the skills they have are higher than the skills required for the job. Under-education/ under-qualification refers to workers whose qualifications are lower than that required by their occupation (Kiker,Santos& De Oliveira 1997; Hung, 2008 ;Quintini,2011).) . If there are, does it lead to lower average returns to education? Henceforth, we aim to contribute to the literature by studying the effects of educational mismatch on private returns to education at different level of certificates qualifications in Malaysian economics sectors. This issue has not been addressed well in the Malaysian context. Only recently, Zainizam, (2013) examined the effect of over-education and under-education on returns to education in the manufacturing sectors. However, the estimation of the earnings function function is remains limited to use level of education (The level of education is more general, due to its measure of groups of people who were at school for a certain period of time, but who may not have achieved the equivalent qualification level. For instance, those people with secondary education (Form 3) do not necessarily have the Lower Certificate Education (LCE). This may likely occur because people perhaps did not complete their schooling or they left school before sitting for the examinations that would enable them to obtain a certificate. In the case of tertiary education, in the HIS survey people are classed as having tertiary education if they hold a diploma, or degree qualifications. Important to note that, tertiary education does not necessarily mean people undertaking studies at the university level. The classification by level of education makes it difficult to accurately identify the years of schooling for diploma and degree qualifications.) .

Research Question

i. How do the private returns to education which is measured by the highest certificate qualification or “sheepskin effects” provide more accurate information about the returns to education in Malaysia?

ii. Do the private returns to education at all levels of qualification show a positive relationship with earnings?

iii. Do the private returns to education increase with the level of certificates qualification (sheepskin effects)?

iv. Did the trend of private returns to education at different levels of qualification increased between 2002 and 2007?

v. Are there incidences of educational mismatches (over and under educated) in the financial sector?

vi. Does educational mismatches occur amongst workers with degree qualifications?

vii. Does over-education lead to lower average returns to education for degree workers?

iv. Are there any qualification differences among over-education workers?

Purpose of the study

The general aim of this study is to investigate the private returns to education at different levels of qualification in Malaysian Financial sector. First, we focus on education as a private decision to invest in 'human capital'. We estimate the returns to education use the highest certificate of qualification or “sheepskin effects” in the Malaysian financial sector. In particular, the paper draws attention to the role of so-called sheepskin effects, defined as the gain in earnings associated with a receipt of degree, controlling the types of occupations (Robst, 2007).

Secondly, we analyse the trend of returns to education at different levels based on the highest certificate qualification achieved in the financial sector between 2002 and 2007. In particular, the analysis focuses on how these returns varied over the period, and how the returns varied according to the highest level of qualification obtained. Thirdly, we examine whether the declining returns to education is due to both educational mismatches. Following Kiker, Santos and De Oliveira (1997), we use self-assessment method to measure both the over-educated and under-educated phenomena by comparing the level of highest certificate qualification reached by individual with occupations. Although we employ a simple technique to measure the educational mismatch, this type of study is quite rare not only in Malaysia, but also across developing nations. The outcome of this analysis is capable to provide preliminary illustration pertaining to the over-education in the returns, especially at higher education level in the Malaysian labour market. Matching between a person’s job and his/her education and skills is important to efficiently manage the human capital stock in the work force.

Literature Review

The estimation of the economic return to education using the level of formal education have attracted considerable attention in theoretical works since the early 1960s(Psacharopoulos, 1981,1985). The results are mixed; However, the estimations of returns to education at the certificates qualification level, that is the “sheepskin effects,” is still under scrutiny1(Trostel & Walker, 2004). Consisent with both human capital and screening/signalling theories, myriad evidences on returns to education show that the credentialed workers (those with high school diplomas or college degrees) earn more than their non-credentialed counterparts. Park (1999) revealed that there is a linear relationship between earnings and sheepskin effects. The return for bachelor’s degree workers is 21% compared to workers with an associate degree and high-school diploma, which are 11% and 9%, respectively. Quinn and Rubb (2006) found that wages increased by 6.5% for those workers with additional years of schooling, particularly for male workers. This study showed that educational attainment is positively linked with wages since the increase in the number of workers with tertiary education is in line with the requirements of the firm. On the demand side, the increase in demand for workers with degree qualifications is also in line with the effect of technological change because educated workers are more likely to adopt new technology and thus are paid higher accordingly (Beblavy, Teteryatnikova &Thum,2013; Acemoglu, 2002; Bartel & Sicherman, 1997).

Even though there are growing number of studies that have investigated the sheepskin effects in the returns to education, most of these studies have only focused on gender, etnicity, countries, broad subject groups and more narrowly defined discipline(e.g: Liu, Belfield & Trimble,2015;Bol& Van de Werfhorst, 2011; De Silva, 2009;O’Leary & Sloane , 2005;Antelius,2000;Jaeger d Page, 1996). Less attention has been given to estimate the private returns to education in the economics sector. Among the recent studies, Thrane (2010) is the first study that investigates the private returns to education in the Norwegian tourism industry. The results showed statistically and economically significant sheepskin effects, with the returns to educational degrees clearly exceeding the returns to years of schooling for both male and female employees. Liu, Belfield and Trimble (2015) showed that the returns to associate and bachelor's degrees remain strong over the late 2000s despite the great recession in the North Carolina. The returns to certificates and diplomas were weak. From the students’ perspective, this study showed that the completion of an associate degree appears to be a very high-yielding investment. However, most of these studies as mentioned above focus on developed countries. Alba-Ramírez and San Segundo (1995) indicated that secondary education is better compensated in the private sector, whereas a university degree receives a greater rate of return in the public sector in Spain. The return to university education is higher among women than among men regardless of the class of worker and the sector of employment.

Even though the returns to education increased according to credentials and additional years of schooling, but, many recent studies show that there is a non-linear specification between earnings and sheepskin effect that can in some circumstances lead to a decline in the returns to education because of a mismatch between the level of educational attainment and occupational requirements (over-educated or under-educated). The determinants and consequences of mismatches between the education profile and the requirements of a firm for certain occupations have been found to have a large documented effect since the study by Freeman (1977). The empirical literature on educational mismatch typically discusses three kinds of measures: (i) those based on contrasts between the actual distribution of workers’ educational attainment and an (estimated) adequate level of education per occupation; (ii) those based on the contrast between the educational level of workers and the required level of education for their job, derived from systematic evaluation by job analysts who specify the required level of education for the job titles in an occupational classification (Joop Hartog, 1980); and (iii) direct measures of education mismatch based on workers’ self-assessments (Sicherman & Galor, 1990).

The declining returns to education for degrees’ holders is closely associated with the fall in the value of a degree for those workers particularly for young graduates who fail to get a graduate-level job. Among the recent study in developed country, Robst (2007) showed that 20% of workers reported that their work was not related to their degree field in Mexico. Lamo and Messina (2010) showed that more than 12% of workers were formally over-educated for their jobs in Estonia. Murillo, Rahona-López, and Salinas-Jiménez (2012) indicated that returns to education have declined since the mid-nineties in Spain. Murillo et.al (2012), found that the return associated with the job's required education is greater than that corresponding to the worker's actual schooling, and that the return on an additional year of attained education is positive but less than that of an additional year of required education. This study showed that, the existence of educational mismatch points to inefficiencies in the allocation of the educational resources. Yakusheva (2010) showed that people whose occupations better match their degree fields earn significantly higher returns to post-secondary schooling. This result is robust to controlling for an extensive set of pre-existing differences among individuals, and to accounting for differences in earnings across post-secondary degree fields. Unlike other empirical studies, Allen and Van der Velden (2001) and Badillo Amador, López Nicolás, and Vila (2012) showed that the impacts of both educational and skill mismatches emerge as a much better predictor of job satisfaction. However, the skill mismatches were much better predictors of job satisfaction and on‐the‐job search compared to educational mismatches as the effects of the latter are related to unobserved heterogeneity among workers. These results contradicts the theory of assignment (The theory of assignment discusses on the problem of assigning workers to jobs (Sattinger, 1993). The theory states that a highly educated individual are more likely to be matched with job vacancies. However, in some circumstances, the matching process may not be perfect especially when too many workers vie for a specific position. This may lead to some individuals being assigned jobs lower down the hierarchy. For instance, workers may be over-educated, whilst others prove to be under-educated.) .

Not many studies have explored the effects of educational mismatch on returns to education in developing countries.Quinn and Rubb ( 2006) have explored the effect in Mexico while Abbas (2008) explored the effect in Pakistan. The empirical findings of these studies agree that the returns to over-education are positive and significant, with the size of the returns being bring less than returns to required level of education. They also find that the returns to under-education to be negative with the magnitude being smaller than the returns to required-education in absolute terms (Hartog, 2000). In the context of Malaysia, studies on the effects of over-education and under-education have primarily focused on the monetary outcome, but a few studies have ventured into the negative impact of overeducation on job satisfaction (Zakariya & Battu, 2013). A recent study by Zakariya et al., 2015 showed that over-educated workers tend to suffer from wage penalty (around 9 to 11%) while undereducated workers enjoy wage premium (around 9 to 12%). Over-educated workers earn less than their well-matched co-workers in similar jobs.

In terms of firm productivity, Kampelmann and Rycx (2012) provide first evidence regarding the direct impact of educational mismatch on firm productivity in Belgium during the period of 1999–2006. After controlling for simultaneity issues, time-invariant unobserved workplace characteristics, cohort effects and dynamics in the adjustment process of productivity, this study clearly showed that a higher level of required education exerts a significantly positive influence on firm productivity as well as an additional years of over-education (both among young and older workers) are beneficial for firm productivity. However, they found that additional years of under-education (among young workers) are detrimental for firm productivity.

Scope of Study

The present study uses the Malaysian Household Income Survey (HIS) for the year 2002, 2004 and 2007. The HIS was conducted by the Malaysian Economic Planning Unit (EPU) and Malaysian Department of Statistic (MDOS). The HIS is one of the most comprehensive surveys of individuals’ earnings in Malaysia that analyses the returns to education at different levels of certificates qualification in the economy sector, making it an ideal data source for this research. The latest HIS data is in 2012. But the classification of certificates of qualifications was changed after 2007, so it difficult the estimate the average private returns. In fact, the data released after 2007 only covers 15% from total survey. As a result, it may not be sufficient to provide the analysis of trend of returns to education in Malaysia. The data used in our study covers more than 40% of the total survey samples.

This study is mainly focused on the on the financial sector. Under the Economic Transformation Programme (ETP), the Financial Services National Key Economic Area (NKEA) is focused on developing Malaysia’s financial industry, which represents a core component and key driver of the Malaysian economy, in tandem with the needs of a high-income nation. The entry point projects ( EPPs) of this NKEA are aimed at addressing challenges faced by the industry in achieving its next stages of growth. These include a lack of scale in certain segments of the banking industry, limitations in the types of investors, products, and currencies available in the capital market, the need to improve personal financial literacy and the need for the local industry to operate in a competitive environment regionally (EPU, 2010).

This study covers the period of 2000-2007. This study aims to oversee the trend of returns to education at different level of certificates qualification during the period from 2000 to 2007.The period is selected because the severe economic crisis of 1998 may be responsible for affecting the returns to education during the period of consideration. This period cover the time after the Asian financial crisis and before the onset of the global financial crisis. The Malaysian labour market was strong in 2002 but there were retrenchments in 2007, and as a result some occupational groups suffered a decline in their mean monthly wages in certain economic sectors (Abidin&Rasiah, 2009). Due to the labour market tightening in 2007 and changes in the economy towards knowledge driven productivity driven, some employers hired potential individuals in line with the requirement of the firm. As a consequence, increase in income did not match with the level of education and the decreasing returns to education in certain economic sectors arised due to lack of skill as demanded by the firms.

Data Description

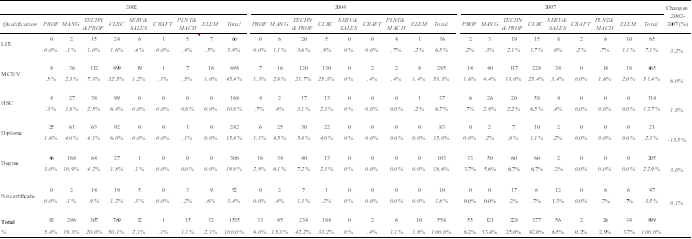

Since the purpose of this study is to investigate the returns to education at different levels of certificates qualification, there are several aspects that must be considered when performing sample selection. First, the number of people chosen is restricted to those employees who are between the ages of 15 and 64 in spite of the data collected by MDOS which consists of individuals aged from 0 to 99. Secondly, the sample selection in this study is restricted to those individuals who have completed their schooling at highest certificate qualification and excludes individuals who did not attend school or those workers who have no formal educational qualifications. The sample also does not cover those people who have received a traditional Islamic education or those, mainly migrant workers, who have qualifications which are not recognised within the Malaysian education system by the Ministry of Education. Thirdly, the sample chosen is also restricted to employed individuals. They are employers and workers either in private or government sectors and thus, the self-employed or those who work on their account are excluded. The exclusion of the self-employed is because of the problems associated with the measurement of self-employment income (McNabb&Said, 2013). Similarly for unpaid family workers or those working without pay, housewives, people looking after the home, students, pensioners, children not at school and those who have never worked are outright excluded from the sample. In addition, unpaid family workers may also be classed as self-employed. Based on the selection criteria, total sample size used in this study and the breakdown of the sample by individual’s highest level of certificate qualification in the financial sector are shown in

Empirical Methodology

This section presents the empirical methodology used to investigate the returns to education in the Financial sector. We employ an extended Mincer model (1974) in which additional variables influencing earnings, apart from education and experience, are included. The model is presented as follows:

where:

A series of dummy variables are included representing types of occupations (

There are nine occupational categories created from the 2-digit occupational code following the Malaysia Standard Classification of Occupations (MASCO) code, 2008, as shown in

As a common practice in the literature, the average private returns to education () for each qualification level is measured by comparing to the level below Kenayathulla, 2013; Katz & Murphy, 1992). It is calculated using the estimated OLS coefficients in the following way: =(-)/ (-) ; where:

This study employs OLS estimators to analyse the returns to education at different levels of certificates qualification in the financial sector. The application of the OLS estimator in the present study is sufficient to interpret the result in line with the objective of this study to analyse the trend of returns to education at different levels of certificates qualification during the period of 2002 to 2007. Although the methodology employ is only regression analysis, but the outcome of this analysis still be able to provide preliminary picture about returns to education at different level of certificates qualification in Malaysian economics sector .

In order to deal with the heteroscedasticity problem due to unobserved heterogeneity (i.e health, and family background characteristics), this study employs the OLS estimator by using regression with a robust standard errors as suggested by Huber (1992).This technique has been applied by Black, Devereux, and Salvanes (2003) to analyse employment earnings across industries. The result is estimated by using regression with a robust standard errors is safe to deal with the heteroscedasticity problem because we usually do not know the structure of heteroskedasticity (especially in our case, the sample size is large). Even if there is no heteroskedasticity, the robust standard errors will become just conventional OLS standard errors. In fact, the robust standard errors are appropriate even under homoskedasticity . The robust standard errors option in regression is also efficiently to deals with the minor problem of normality as some observations may exhibit large residuals, leverage or influence as well as to capture the possible concerns about the effects of serial correlation on the standard errors (Black et al., 2003).

Result and Discussion

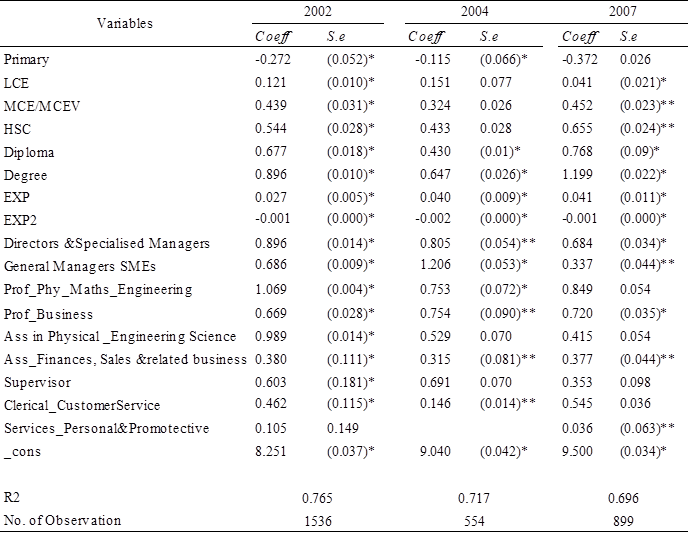

This section presents the parameter estimates for the earnings equation (1). The regression results are presented in Table

The negative correlation between education and earning can be related to the individual’s decision to make investment on education. Due to the cost of education that varies across individuals, it is possible to have differences in the access to credit markets. Empirical studies show that the credit constraint tends to occur for poor families or parents from poor social economy status in providing education to their children (Psacharopoulos, 1994).

This result is in line with the financial sector’s requirement for educated workers during the transition process to a knowledge-based economy with skills identified as the new factor of production in the new economy; possessing the right mix of skills will ensure the banking industry’s competitive edge in the global economy. A recent study shows that, most financial companies such as Jabil Sdn. Bhd. (JSB) and The Lion Group (TLG) reported a first degree in finance, management, accounting or economics as prerequisites for the post of Assistant Manager (Business Development) and Personal Assistant Director (Omar, Abdul Manaf, Mohd, Che Kassim, & Abd. Aziz, 2012). Consistently, as indicated in

This situation shows that there are over-educated degree workers in the financial sector because they are employed in a non-graduate job position (We use skill level concept to determine the occurrences of both educational mismatches in our analysis. According to MASCO 2008, the occupational classification based on the concept of skill (educational level) is as follows: (i) Primary education for elementary occupation. ii) Secondary or post-secondary education; Malaysian Skills Certificate (SKM) Level 1-3 for Clerical Support Workers, Service and Sales Workers, Skilled Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Workers, Craft and Related Trades Workers and Plant and Machine-operators and Assemblers; iii) tertiary education leading to an award not equivalent to a first University Level; Malaysian Skills Certificate (SKM) Level 4 or Malaysian Skills Diploma (DKM) Level 4 for Technician and associate professional; iv) tertiary education leading to a University or postgraduate university degree; Malaysian Skills Advanced Diploma (DLKM) Level 5-8 for professional category.) . The share of degree workers for professional category shows an increasing trend by 1.1% between 2002 and 2007. Meanwhile, demand for degree-educated workers for technicians and associate professional and clerks and related occupation groups show the similar patterns with increases by 4.7% and 2.5% respectively over the same period. However, it interesting to report that, our results contradicts with some empirical studies that show that over-educated employees may under-earn below those in graduate jobs position, hence reducing both the private and social rates of return (Seamus McGuinness & Sloane, 2011; Dolton & Silles, 2008; Van der Meer, 2006; Frenette, 2004). Further, most of the literature in this field that has estimated the effect of over-education on earnings has confirmed that the over-educated earn less than their peers in graduate jobs. Furthermore, several studies have shown that over-educated workers are less productive than correctly allocated workers with the same formal qualifications(e.g: Green & Zhu, 2010; Murillo, Rahona-López & Salinas-Jiménez, 2012; Verhaest & Omey, 2006).

There is possible explanation for the high returns of over-education for degree-educated workers in the financial sector between 2002 and 2007. Our result may be consistent with the signalling hypothesis which that over-education is an indication to the employer that the worker is more productive compared to the adequately educated worker and the under-educated worker and therefore they receive higher returns. The over-educated workers influence productivity through a worker’s quality, especially when the workers’ qualities are more than the workers’ productivity in jobs requiring lower skills (Kampelmann& Rycx; 2012;Mahy, Rycx, & Vermeylen, 2013). Further, employers are willing to offer those workers a chance to contribute to higher productivity, thus enabling and transforming the companies into a more flexible and adaptable entity in response to the changing market needs.

Consistently with the current situation in Malaysian financial sector, demand for medium-skilled occupation has increased especially in the clerical and related occupation. This is due to increase in competition among retail banks and prestigious employers in financial service sectors which has lead to outbidding by employers for both qualified professionals and clerical and related occupations, particularly for both teller and customer services clerks. Most of the banking institutions compete for graduates, particularly for teller positions, as the teller plays a significant role in the banking institution for its close association with customer services. The increment in demand thus shifts the entry point of educational requirement from SPM (O-levels equivalent) qualification to at least a diploma and above (Leng, 2012).

A notable finding of our study is the returns to education do not increase according to levels of certificates qualification and additional years of schooling. This result contradicts the human capital theory but supports the screening theories regarding the relationship between education and earnings. This can be clearly observed for diploma workers. The average returns for workers with diploma is lower return compared to those with MCE/MCEV and HSC qualifications during the period under investigation. For example, in 2007, the average returns for both workers with MCE/MCEV and HSC are at 20.54% and 13.79%, respectively, compared to diploma workers at 7.53%. Our result is consistent with

Nevertheless, our results clearly show that there is under-education situation that occurs among the MCE/MCEV workers for technician and associate professional job categories. According to the job classification based on skill level in Malaysia, those workers with MCE/MCEV qualification is matched to be employed in the clerical, sales and services and craft and related workers occupational categories8. This result clearly indicates that the labour market in the Malaysian financial sector remained favourable for semi-skilled workers even though workers with MCE/MCEV qualification are under-educated. Our results supports the signalling or screening theory that claims the increase in returns to education for MCE/MCEV workers is due to their ability to persistently maintain their productivity-unrelated earnings advantage over the required-education (Spence, 1973; Groot & Oosterbeek, 1994).

The main concern here is regarding the negative average private returns and declining average returns for diploma-educated workers. The negative returns can be seen in 2004 which is at -0.28%. The result shows that trend of average returns for diplomas holder declined by 1.29% between 2002 and 2007. Consistently, the data in

Previous studies support that the decline in returns to education shows that this qualification could be perceived by employers as a negative signal of the ability of individuals who have acquired them (Jenkins, Greenwood, & Vignoles, 2007). The result signifies a shortage of workers with a diploma on technical skills (i.e. computer/IT skills) and non-technical skills such as interpersonal and communication skills, thus explaining the fall in the average return. The results signal that furthering education at higher level is necessary for wage gain even though it does not match the required education for a particular job.

The focus is now on the returns associated with different occupations in the financial sector. The result in

With regards to returns to experience, it is surprising to note that returns to experience persistently increases from 2.78% to 4.20%,

Conclusion and Policy Implication

The present study examines the private returns to education using the certificates of qualification in the Malaysian financial sector during the years 2002–2007. Our results indicate the presence of an over-education situation among degree-educated workers despite enjoying higher private returns. Such over-qualification in the financial sector is due to the mismatches in the supply of degree-educated workers for medium-skilled positions, which is now outstripping the supply of high-skilled workers.

Interesting to note that, our results contradict most previous empirical studies. Many evidences support that the private returns for over-educated and under-educated workers will fall because they may be dissatisfied with their current job and drop their productivity level of the firm(e.g: Green&Zhu, 2010;Murillo, Rahona-López&Salinas-Jiménez,2012; Verhaest&Omey,2006). Hence, our study contribute to the literature by explaining the phenomenon of over/under-education using signalling hypothesis (Spence, 1973; Groot & Oosterbeek, 1994).

From a policy perspective, it is important to highlight that the existence of education-occupation mismatches will lead to inefficiency in the allocation of the educational resources that subsequently may jeopardize workers’ returns to education (Zakariya,2015; McGuinness & Bennett, 2007). Hence, we suggest that any investment in education needs to include the actual skill supply. If the qualification reflects the actual skill level, the over-educated will also be equipped with over-skill. Given the intense process of human capital accumulation undergone by the Malaysian economy, it would be necessary to tackle the structural reforms needed in order to take advantage of this investment. This effort is to ensure that the higher-educated and thus higher skilled individuals have an advantage in securing employment in lower-skilled jobs, crowding out the employment opportunities for those with lower levels of education. Regarding the declining returns to education for diploma workers, we suggest the Malaysian government to reform education and training to equip job seekers with the skills and knowledge needed to succeed in getting a suitable job in the Malaysian labour market. It is imperative to develop the educational and training systems in order to meet the new needs of the labour market.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the

References

- Abidin, M. Z., & Rasiah, R. (2009). The global financial crisis and the Malaysian economy: Impact and responses. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Malaysia.

- Alba-Ramírez, A., & San Segundo, M. J. (1995). The returns to education in Spain. Economics of Education Review, 14(2), 155–166.

- Allen, J., & Van der Velden, R. (2001). Educational mismatches versus skill mismatches: effects on wages, job satisfaction, and on‐the‐job search. Oxford Economic Papers, 53(3), 434–452.

- Antelius, J. (2000). Sheepskin effects in the returns to education: evidence on Swedish data. FIEF Working Paper Series. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/fiefwp/0158.html

- Badillo Amador, L., López Nicolás, Á., & Vila, L. E. (2012). The consequences on job satisfaction of job–worker educational and skill mismatches in the Spanish labour market: a panel analysis. Applied Economics Letters, 19(4), 319–324.

- Beblavy, M., Teteryatnikova, M., & Thum, A.-E. (2013). Expansion of higher education and declining quality of degrees. NEUJOBS Working Paper (Vol. 4.4.2. B). Retrieved from http://www.neujobs.eu/sites/default/files/NEUJOBS_Del_442_b.pdf

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: a theoretical analysis with special reference to education. National Bureau for Economic Research, Columbia University Press, New York and London.

- Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2003). Why the apple doesn’t fall far: Understanding intergenerational transmission of human capital. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Blundell, R., Dearden, L., & Sianesi, B. (2004). Evaluating the Impact of Education on Earnings in the UK: Models, Methods and Results from the NCDS. Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Bol, T., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2011). Signals and closure by degrees: The education effect across 15 European countries. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 29(1), 119–132.

- Cellini, S. R., & Chaudhary, L. (2014). The labor market returns to a for-profit college education. Economics of Education Review, 43(0), 125–140. http://doi.org/DOI:

- De Silva, I. (2009). Ethnicity and Sheepskin Effects in the Returns to Education in Sri Lanka: A Conditional Quantile Analysis. International Journal of Development Issues, 8(1), 61–79. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,url,shib&db=eoh&AN=1052914&site=ehost-live\nhttp://www.econ.usyd.edu.au/IJDI/

- Dolton, P. J., & Silles, M. A. (2008). The effects of over-education on earnings in the graduate labour market. Economics of Education Review, 27(2), 125–139.

- EPU. (2010). Tenth Malaysia Plan 2011-2015. Putrajaya: EPU, Prime Minister’s Department.

- EPU, & Bank, W. (2012). Malaysia Economic Monitor. Chapter3: Modern jobs: higher wages, secure workers, competitive firms. Malaysia: Economic Planning Unit.

- Freeman, R. B. (1977). The overeducated American. New York: Academic Press.

- Frenette, M. (2004). The overqualified Canadian graduate: the role of the academic program in the incidence, persistence, and economic returns to overqualification. Economics of Education Review, 23(1), 29–45.

- Green, F., & Zhu, Y. (2010). Overqualification, job dissatisfaction, and increasing dispersion in the returns to graduate education. Oxford Economic Papers, 62(4), 740–763.

- Groot, W., & Oosterbeek, H. (1994). Earnings Effects of Different Components of Schooling; Human Capital Versus Screening. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 76(2), 317–321.

- Harmon, C., Oosterbeek, H., & Walker, I. (2003). The Returns to Education: Microeconomics. Journal of Economic Surveys, 17(2), 115–156.

- Hartog, J. (1980). Earnings and capability requirements. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 62(2), 230–240.

- Hartog, J. (2000). Human Capital as an Instrument of Analysis for the Economics of Education. European Journal of Education, 35(1), 7–20.

- Heywood, J. S. (1994). How widespread are sheepskin returns to education in the U.S.? Economics of Education Review, 13(3), 227–234. http://doi.org/DOI:

- Huber, P. J. (1992). Robust Estimation of a Location Parameter. In Breakthroughs in Statistics (pp. 492–518). Springer.

- Hungerford, T., & Solon, G. (1987). Sheepskin effects in the returns to education. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 175–177.

- Jaeger, D. A., & Page, M. E. (1996). Degrees Matter: New Evidence on Sheepskin Effects in the Returns to Education. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(4), 733–740.

- Jenkins, A., Greenwood, C., & Vignoles, A. (2007). The returns to qualifications in England: updating the evidence base on level 2 and level 3 vocational qualifications. Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Kampelmann, S., & Rycx, F. (2012). The impact of educational mismatch on firm productivity: Evidence from linked panel data. Economics of Education Review, 31(6), 918–931. http://doi.org/DOI:

- Kenayathulla, H. B. (2013). Higher levels of education for higher private returns: New evidence from Malaysia. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(4), 380–393.

- Kiker, B. F., Santos, M. C., & De Oliveira, M. M. (1997). Overeducation and undereducation: Evidence for Portugal. Economics of Education Review, 16(2), 111–125.

- Lamo, A., & Messina, J. (2010). Formal education, mismatch and wages after transition: Assessing the impact of unobserved heterogeneity using matching estimators. Economics of Education Review, 29(6), 1086–1099.

- Leng, K. S. (2012). From tellers to sellers to thinkers: the case of Malaysian banks. Journal of Human Capital Development, ISSN: 1985.

- Liu, V. Y. T., Belfield, C. R., & Trimble, M. J. (2015). The medium-term labor market returns to community college awards: Evidence from North Carolina. Economics of Education Review, 44, 42–55.

- Mahy, B., Rycx, F., & Vermeylen, G. (2013). Educational Mismatch and Firm Productivity: Do Skills, Technology and Uncertainty Matter?

- McGuinness, S., & Bennett, J. (2007). Overeducation in the graduate labour market: A quantile regression approach. Economics of Education Review, 26(5), 521–531.

- McGuinness, S., & Sloane, P. J. (2011). Labour market mismatch among UK graduates: An analysis using REFLEX data. Economics of Education Review, 30(1), 130–145.

- McNabb, R., & Said, R. (2013). Trade Openness and Wage Inequality: Evidence for Malaysia. The Journal of Development Studies, (ahead-of-print), 1–15.

- Murillo, I. P., Rahona-López, M., & Salinas-Jiménez, M. del M. (2012a). Effects of educational mismatch on private returns to education: An analysis of the Spanish case (1995-2006). Journal of Policy Modeling, 34(5), 646–659.

- Murillo, I. P., Rahona-López, M., & Salinas-Jiménez, M. del M. (2012b). Effects of educational mismatch on private returns to education: An analysis of the Spanish case (1995–2006). Journal of Policy Modeling, 34(5), 646–659.

- O’Leary, N. C., & Sloane, P. J. (2005). The return to a university education in Great Britain. National Institute Economic Review, 193(1), 75–89.

- Omar, N. H., Manaf, A. A., Mohd, R. H., Kassim, A. C., & Aziz, K. A. (2012). Graduates’ employability skills based on current job demand through electronic advertisement. Asian Social Science, 8(9), 103–110.

- Park, J. H. (1999). Estimation of sheepskin effects using the old and the new measures of educational attainment in the Current Population Survey. Economics Letters, 62(2), 237–240. http://doi.org/DOI:

- Psacharopoulos, G. (1981). Returns to education: an updated international comparison. Comparative Education, 17(3), 321–341.

- Psacharopoulos, G. (1985). Returns to education: a further international update and implications. Journal of Human Resources, 20(4).

- Psacharopoulos, G., & Patrinos, H. A. (2004). Returns to investment in education: a further update. Education Economics, 12(2), 111–134.

- Quinn, M. A., & Rubb, S. (2006). Mexico’s labor market: The importance of education-occupation matching on wages and productivity in developing countries. Economics of Education Review, 25(2), 147–156.

- Quintini, G. (2011). Right for the Job: Over-qualified or Under-skilled? OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers (No. 120).

- Robst, J. (2007). Education and job match: The relatedness of college major and work. Economics of Education Review, 26(4), 397–407.

- Robst, J. (2007). Education, college major, and job match: Gender differences in reasons for mismatch. Education Economics, 15(2), 159–175.

- Sattinger, M. (1993). Assignment models of the distribution of earnings. Journal of Economic Literature, 18(2), 831–880.

- Sicherman, N., & Galor, O. (1990). A theory of career mobility. Journal of Political Economy, 169–192.

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374.

- Thrane, C. (2010). Education and earnings in the tourism industry - The role of sheepskin effects. Tourism Economics, 16(3), 549–563.

- Trostel, P., & Walker, I. (2004). Sheepskin effects in work behaviour. Applied Economics, 36(17), 1959–1966.

- Verhaest, D., & Omey, E. (2006). Discriminating between alternative measures of over-education. Applied Economics, 38(18), 2113–2120.

- Yakusheva, O. (2010). Return to college education revisited: Is relevance relevant? Economics of Education Review, 29(6), 1125–1142.

- Zainizam, Z. (2013). Returns to Education : What Does Over-education Play ? Prosiding Perkem Viii, 1(8), 266–278.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-016-7

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

17

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-471

Subjects

Business, management, behavioural management, macroeconomics, behavioural science, behavioural sales, behavioural marketing

Cite this article as:

Yunus, N. M., & Hamid, F. S. (2016). The Effects of Over-Education on Returns in the Graduate Labour Market. In R. X. Thambusamy, M. Y. Minas, & Z. Bekirogullari (Eds.), Business & Economics - BE-ci 2016, vol 17. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 384-403). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.02.35