Abstract

Due to increasing specialization, outsourcing and competition from the globalization process, family businesses are under more pressure than ever to innovate and improve performance (

Keywords: Family cultureInnovationFamily Business PerformanceStructural Equation Modelling

Introduction

Existing researches have highlighted that innovation is closely linked with business performance (e.g., Damanpour, Walker, & Avellaneda, 2009). This existing literature have provided clear evidence that innovation, as the driving force of performance in a market economy, plays a crucial role to long term profitability and growth in business. However, up-to-date, little attention has been given to innovation in the family business. Even in pertaining researches carried out in the past, the focuses are normally on the family versus nonfamily business dichotomy on innovation performance. However, in reality, the family business is multidimensional and continuous. The pattern of family culture varies from business to business. This study seeks to fill these gaps by exploring the links between family culture, innovation and business performance.

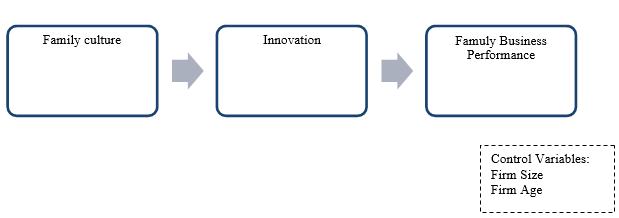

With the aim to fill in this gap in the literature, a theoretical framework (Fig. 1.) based upon previous research in family business and innovation literature is established to analyze the impact of family culture on innovation and family business performance. Accordingly, testable hypotheses for the proposed framework are developed. In addition, the relationships between family culture, innovation and business performance are empirically tested with Amos in Structural Equation Modeling. The mediating role of innovation to the relationship of family culture and business performance is tested as well.

This study contributes to family business research in three ways. The primary contribution of this study is the examination of the potential mediating effect of innovation on the family culture → business performance relationships. The second contribution is the development of a theoretical framework that linked between family culture, innovation and family business performance. Finally, this study contributes to formal research in the field of family business in Malaysia, where there is a great need for information from empirical studies.

Literature Review

Defining Family Business

The field of family business is relatively young and emergent in organizational research (Handler, 1989). Furthermore, the family business concept is rooted in and lies at the intersection of several social science, sociology, anthropology, social psychology and organizational behavior, and reflects some of the biases of each (Alderson, 2011). Hence unlike other concepts, family business has no single unanimously accepted definition (Astrachan, 2010). Lansberg, Perrow, & Rogolsky (1988) in the first issue of the Family Business Review have pointed out that “ a variety of definitions are being used in the field” (p. 7). Almost every writer has his or her own definition. Nevertheless, it is generally accepted by researchers that family involvement differentiates family business from non-family business (Miller, 2003).

In this research, the author subscribes to the Astrachan, Klein, & Smyrnios’ (2002) definition of family business. The Astrachan, Klein, & Smyrnios’ (2002) definition provides a more fitting foundation for questions concerning the heterogeneity of family business and the dominant role of the owning family in the business. Rather than defining family businesses dichotomously, the definition used by Astrachan, et al (2002) conceptualizes and operationalizes the level of family influence on the business. Their definition focuses on assessing the degree of family influence and involvement that the owning family wields over a business. In light of the evidence that a family can exert influence over a business (e.g., Yener & Akyol, 2009), as well as an argument that the owning family of the family firm is both an important component of leadership and plays a critical role in the formation its innovative behavior and business performance in a firm, the authors believe that this is the appropriate definition of family business for this research.

2.2 Family Culture

Family culture in this study refers to the shared family and business values (Carlock &Ward, 2001) as well as the family’s commitment to the firm (Zahra, Hayton, Neubaum, Dibrell & Craig, 2008). It measures the degree to which the value system of the business is influenced by the family. A large overlap between family values and business values indicates a significant influence of the family culture on the business (Zahra, et.al, 2008).

Carlock and Ward (2001) postulated that the value of owning family will have impact on the family’s commitment to the business and family business performance. They further argued that the family’s commitment is affected by three factors. First, personal belief and support toward the business’s goals and vision determine the level family members willingness to commit to the business (Lyman, 1991). Second, the willingness of family members to contribute to the business is positively associated with business performance (Klein & Mühlebach, 2004). Finally, the greater the business families' desire to relate with the business, the better the family business to achieve and sustain competitive advantage over time (Martínez, Bernhard, & Bernardo, 2007; McConaugby, Matthews, & Fialko, 2001).

2.3 Innovation

Studies of innovation have a long academic lineage. Indeed, scholars such as Damanpour, Walker and Avellaneda (2009) noted that “The study of innovation hardly needs justification as scholars, policy makers, business executives, and public administrators maintain that innovation is a primary source of economic growth, industrial change, competitive advantage, and public service” (p. 650). The innovation side of a family business is critical to its survival, prosperity and continuity (Poza, 2009).

Coupled with the numerous articulation of innovation, there are multiple strands and resulting innovation measures (Rogers, 1998). The variety and number of innovation measures further augments the ambiguity shrouding innovation. Regardless of the measure applied, most measures of innovation include the concept of intentional change, introduction of new product/process or new ideas generation (Lam, 2006). Indeed, Litz and Kleysen (2001) pointed out that innovation in the family context is “the intentional generation or introduction of novel process and or products resulting from the autonomous and interactive efforts of members of a family” (p. 336). Hence, this study focuses on innovation in terms of new products and process and innovative behavior which entails the actual generation of new ideas. This study reports on the characteristic of innovation follows an ‘outcome-oriented approach’ by drawing attention to the direct impact of innovation on business performance.

Hypotheses

The link between family culture and innovation

Family culture refers to the shared family and business values as well as the family’s commitment to the firm (Astrachan, et al., 2002; Zahra, et al, 2008). It measures the degree to which the value system of the business is influenced by the family. Both popular and academic literatures have long spread the notion that organization culture may have a significant effect on innovation (e.g. Bammens, Van Gils, & Voordeckers, 2010). Nevertheless, there seems to be a paradox that organizational culture can stimulate or hinder innovation (Martins & Terblanche, 2003).

Carlock and Ward (2001) suggested that the value of the owning family has an impact on the family’s commitment to the business and its performance. Indeed, Carlock and Ward (2001) established three principal factors of commitment: i) a personal belief and support of the firm’s goals and visions, ii) a willingness to contribute to the firm, and, iii) a desire for a relationship with the firm. The willingness of family to commit to business (Klein & Mühlebach, 2004) tends to lead the family firm to achieve and sustain competitive advantages over time (Jon I. Martínez, Bernhard S. Stöhr, & Quiroga, 2007).

The kinship ties and reciprocal altruism in the family business may generate higher level of intragroup communication (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007), increased commitment (Goncalo, 2004) and decreased conflict (Gioia, 1999). This open communication, decreased conflict, and increased commitment may lead the organization to have a high level of autonomy, flexibility, and a risk tolerant culture. When members of the business perceive such supportive practice, they will feel motivated to innovate (Simosi & Xenikou, 2010). This high level of autonomy, flexibility, and a risk tolerant culture are consistently found in innovative organizations (Martins & Terblanche, 2003). Innovative family businesses have the capacity to absorb innovation into the organizational culture and management processes (Lendel & Varmus, 2011). As observed, the culture of flexibility, autonomy and cooperative teamwork will promote innovation in family businesses.

While business altruism and long term management tenure by family members make a family business more apt to exploration of innovation idea, it also may lead to rigid structures that inhibit innovation. Family businesses particularly established family businesses are inclined toward survive on order, measurement, and predictability (Hickman & Raia, 2002). The norms of rigidity, control, predictability, stability and order in established family businesses may foster a culture of unwillingness to make a mistake or take a risk. The family business may embrace a consistent and continuous reality than tolerate the odd and disruptive ways innovation brings to the business.

As evidence from previous literature, there is no consensus among researchers on the impact of culture in innovation. The disagreement on the previous studies resulted difficulty in determining the direction of relationship between culture and innovation. Nevertheless, it is generally accepted by researchers that culture has direct effect on innovation. Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested.

The link between family culture and business performance

Family businesses are often motivated by factors other than straightforward profit maximization. Family values frequently influence business decision-making and are often deemed more important than economic concerns (Alderson, 2011). Agency problems can arise when the family’s goals are differ from the business goals (Oswald, Muse, & Rutherford, 2009). Agency relationship and costs, for instance a self-serving interest of the CEO to win over profit-motive interest of other stakeholders, within family business may make the family culture bad to business performance (Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino, & Buchholtz, 2001). Nevertheless, Bammens, et al. (2010) posited that when family goals and business goals are aligned, family culture can establishes a competitive advantage for family businesses. It is important to mention, that not all of the above characteristics, positive or negative, are present in every family. Nevertheless, they are commonly observed in family businesses.

As evidence from previous literature, there is no consensus among researchers on the impact of family culture on business performance. In brief, although it is clear that family culture has direct effect on business performance, the direction of effects is uncertain. Thus, the following hypotheses are suggested.

The mediating effect of innovation

Panuwatwanich, Stewart, & Mohamed (2008) highlighted that innovation “is the product of social relation relationship and complex systems of interaction” (p. 408). There is an interaction between those who innovate and those who are affected by these innovations; and there is recognition that the innovator’s actions will affect others and this will have an influence on those innovations. As this seems to be the case, it is expected that the culture of the owning family will shape the innovation processes and business performance. Thus, it is suggested that innovation mediates the relationship between family culture and business performance. Hence, the following hypotheses are suggested:

Existing studies suggested that there is a close link between innovation and business performance (Damanpour, et al., 2009). Hence, the following hypothesis is suggested:

Method

4.1 Participants and procedures

This study adopts a purposive sampling. The sample is developed from Bursa Malaysia database in 2011 which has a listing of 962 registered companies. Among these 962 public listed companies, 437 of them are family businesses. Average two board of directors, who have family relationship with other directors or shareholders, were selected from each public listed company. The selection resulted with 872 distributed questionnaires. Multiple respondents were sent to increase response rate. However, only one key informant from each company was allowed.

A total of 193 questionnaires received. However, only 174 response sets were used in the data analysis because 6 respondents were not family members, 11 response sets were blank and 2 respondents were not from the top management team. None of the respondents are from the same company. Thus, the total usable response rate was 12.13%.

4.2 Measures

4.2.1 Dependent variable: Family business performance

Acknowledging the fact that the sample in this study is not limited to one industry but involved companies from various industries, and because the performance of a business depends on the industry, a non-financial-based perspective is used for measuring business performance in this study. Subjective measures of performance are widely used in previous research and are considered effective in comparing business units and industries (Douglas & Judge Jr, 2001; Drew, 1997).

The measures for family business performance were adapted in part from Kelly, Athanassiou, and Crittenden (2000) and Von Buch (2006). The family business performance is measured through asking the family members involved in the top management team to rank the on the following issues: providing family member employment opportunities, the preservation/improvement of the standard of living of the family members, a successful business transfer to the next generation, the minimization of conflicts between family members, the sales growth rate, return on sales (net profit margin), gross profit, net profit after taxes, financial strength (liquidity and ability to raise capital), and overall company performance as compared to the businesses of similar nature over the previous three years. The family business performance variable is assessed using a 5-point Likert-type scale, with 1 being poor and 5 being outstanding. The business performance scale was found to have a reliability of α = 0.837 (Table

4.2.2 Mediating variable: Innovation

The measures for innovation were adapted in part from Avlonitis , Papastathopoulou and Gounaris (2001), Cooper, Easingwood, Edgett, Kleinschmidt, and Storey (1994), and Onne Janssen (2000). Participants were questioned on issues relating to product and process innovation (two items), being ‘first’ to the market (two items), and innovation idea generation (three items). The innovation scale was found to have a reliability of α = 0.894 (Table

4.2.3 Independent variable: Family culture

The measure of family culture is based on the culture scale developed by Astrachan, Klein and Smyrnios (2002). Family culture consists of 9 items and measures the degree of shared family and business values, as well as the family’s commitment to the business. The culture scale was found to have a reliability of α = 0.828 (Table

4.2.4 Control variables: Firm size and firm age

In addition to the above measures, two control variables are included. Firm size and age are used as control variable to control firm effects on innovation and performance. Firm size is measured using the 2011 year end market capitalization. Market capitalization is used because it is more accurate and readily available as compare to number of employees which is highly skewed among the firms in this study. Moreover, investment community uses market capitalization to determine a company’s size (e.g. Joshi & Hanssens, 2010), as opposed to sales or other figures. The age of firm is measured using the logarithm of years since the year incorporated.

Analytic Strategy

The statistical tests used in this study are Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) 20.0 and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with AMOS 20.0. SPSS is used to assess data normality while SEM is utilized for assessing the hypothesized relationship contained in the hypothesized model.

The proposed theoretical framework, portrayed in Figure

Bootstrapping provides a statistical solution where data is not normally distributed and assumptions of large sample size are violated. Unfortunately, this resampling method is prone to be optimistic and more likely to see statistical significant for the data (Byrne, 2010). Hence, Bollen Stine p value which is considered to be a “ Modified bootstrap method for the Chi-square goodness-of-fit statistic” (Byrne, 2010, p. 284) is included to correct for limited sample size. Aside of the Bollen Stine p value test, the .95 corrected confidence intervals are included for examined the overall model fit with non-normal data.

Post hoc estimation of Hoelter’s critical

Results

6.1 Examination of Variables for Factor Analysis Suitability

Suitability of the data set to conduct CFA was examined by the KMO index and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO indices for culture, innovation and business performance were higher than 0.5 as recommended by Hair, Black, & Babin (2010).

6.2 Model Fit

Then, individual CFA is conducted to examine the adequacy of the measurement component of the proposed model. After ensuring an appropriate fit, the author then derived the full structural model from the hypotheses. To gauge model fit, measurement models are assessed by global fit indices and model parameter estimate. Since “no golden rule” exists to determine the most suitable index (Byrne, 2010), multiple indices are used to assess the overall model fit. Both absolute fit indices in combination with relative fit indices are included. These indices consist of the traditional Chi-Square test of model fit, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). The Chi-square has no minimal acceptable value and is skewed by sample size and data normality issue (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Hence, it must be interpreted cautiously.

Table

Based on the CFA’s conducted, all variables displayed reliability, convergent and discriminant validity; and therefore, will be utilized in the structural model. As evidence by the extant literature, a structural model that included family culture, innovation and family business performance has been formed. The intent of this model was to validate a causal structure involving the impact of family culture and innovation on family business performance. In addition, the model was run to examine the impact of the following control variables on innovation and business performance: firm age and firm size. These variables were included to explore whether any of the hypothesized relationship would change in magnitude or strength. This was assessed by examining the global fit of the model to the data and the parameter estimates.

Results are reported here. The model displayed GFI value of 0.899, CFI value of 0.979, TLI value 0.975 and RMSEA value of 0.036, together with a Bollen-Stine bootstrap p value of 0.199 were indicative of adequate fit between the hypothesized model and the sample data (Byrne, 2010).

6.3 Hypothesis Testing

Next, the author examined the path coefficients, critical ratio, p-values, and bootstrap confidence intervals to determine path significance and mediation relationship. Maximum likelihood estimates and bootstrap confidence intervals were displayed in Table

Based on the findings in Table

Although the direct path from firm size to business performance was significant, the removal of this path revealed that no significant impact on other paths and previous significant relationship remained unchanged. By controlling for firm size and firm age when testing models, it was assured that the significance of the relationship between culture, innovation and business performance was due to the intended variables and not these factors. However, the Hypothesized Model in Figure

The author found support for hypotheses 1, 3 and 4, as evidence by the path coefficients, critical ratio, p-values, and bootstrap confidence intervals presented in Table

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the link between family culture, innovation and business performance. The attempt of introduce innovation as a mediator in the family culture – business performance relationship helps one better understand the role of innovation in family business performance. The author finds evidence that family culture is an important asset that could create a distinct advantage for family businesses. Nevertheless, family culture did not affect business performance in a direct manner but in an indirect manner via innovation. Innovation was significantly related to business performance and positively mediated the family culture-business performance. This indicated that management should foster a strong culture of commitment among family members who are involved in the business in order to enhance both business innovation and performance.

The current study found a positive, significant relationship between family culture and innovation. However, it is important to note that four items have been removed from the analysis to improve the goodness-of-fit indices and validity of the scale. The five items that remained reflect the family’s commitment, loyalty and pride toward the company. A review of previous literature indicated that minor changes on family culture subscale is recommended to increase the validity of the concept(Cliff & Jennings, 2005). Cliff & Jennings (2005) argue that the family culture subscale possessed less validity due to linguistic contents of some of its items. Based on the literature review, a slightly modified family culture subscale is acceptable to measure the level of family commitment and the level of overlap between family values and business values.

Overall, two primary theoretical contributions emerge from this study. The first contribution is the development of a theoretical framework that linked between family culture, innovation and family business performance. This study adopted a multi-disciplinary approach that transcends the boundaries of family business and innovation disciplines in the family business literature. It synthesizes diverse writings and arguments that accretes to a theoretical framework. It has theoretically introduced the innovation as the intervening variable on the relationship between family culture and family business performance. Indeed, the innovation as a mediating role in the family culture – business performance relationship is a novel attempt.

A second contribution concerns the use of an international sample. With this, this study expand past western-based research findings to an Asian – specifically, Malaysia – setting. Findings of this study suggest that some of the relationships that have been proposed in the western setting do hold when extended to an international context. As research continues in this area, across both organizational and national settings, this study is building stronger support for the idea that the family’s value and level of commitment to the business has impacted on the business’s innovation and therefore on business performance. This finding is important because it leads to both improved theories of family business and provides some insights into the relationship between the family business, innovation and business performance.

Limitations and Areas of Future Research

This study has limitations. The authors suggest two limitations exist in this study and provide guidelines for future work to address them. The first limitation is related to the cross-sectional nature of the study. The data were collected in a time frame of 6 months. Hence, these data do not adequately capture possible change over time and representing just a given point in time. Furthermore, family business is a very rich phenomenon characterized by abundant subtleties. Cross-sectional research design diminished much of this richness and subtlety. Thus, future research, for example longitudinal design, which can provide more comprehensive view and richness understanding of family business would be preferable on assessing how the link between family culture, innovation and business performance developed over time.

The second limitation is related to the use of single respondent data. Moreover, the sample was limited to family members involved in public listed companies’ top management team that voluntarily answered the survey. While the use of self-selected sample gave entrée to collecting data, this factor could easily have skewed the findings. Their responses might be biased and might not reflect the actual situation. Furthermore, differences in perceptions are expected to occur between various family members (Tagiuri & Davis, 1996). Therefore, the respondents’ responses are unlikely to be representative of those working in non top management team family members. Hence, the extent to which the results can be generalized across a wider population is compromised. How the results concerning the relationship studies might differ in another generational setting is a question for future research. Thus, a useful extension of this study could have used a multi-respondent data collection method. Such approach could provide more accurate information on the relationships between family influence, innovation and business performance. Researchers could determine the differences between generations and how these differences influence the relationship between family influence, innovation, and business performance. Nevertheless, a lower response rate is expected with this approach.

In sum, the findings of this study indicated that an effective culture is about moving business’s innovation forward by unleashing the very best that the business families have to offer while being continually open and responsive to both its stakeholders and to this highly changing world. Undertaking further studies linking innovation with family business will be beneficial for the expansion of the body of knowledge on family business research and strengthening practitioners’ understanding of the complexities of family business. The author hopes that this study provides a foundation for ongoing research into family business’ innovation, and the nature related family influence and their management.

References

- Alderson, K. J. (2011). Understanding the family business: Business Expert Pr.

- Anderson, & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice - a review and recommended 2-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411-423.

- Astrachan, J. H. (2010). Strategy in family business: Toward a multidimensional research agenda. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1(1), 6-14.

- Astrachan, J. H., Klein, S. B., & Smyrnios, K. X. (2002). The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem (1). Family Business Review, 15(1), 45(14).

- Bammens, Y., Van Gils, A., & Voordeckers, W. I. M. (2010). The role of family involvement in fostering an innovation-supportive stewardship culture. Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, 1-6.

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research(16), 78-117.

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.): Taylor & Francis.

- Carlock, R. S., & Ward, J. L. (2001). Strategic planning for the family business: parallel planning to unify the family and business: Palgrave.

- Cliff, J. E., & Jennings, P. D. (2005). Commentary on the Multidimensional Degree of Family Influence Construct and the F-PEC Measurement Instrument. [Article]. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 29(3), 341-347.

- Cooper, R. G., Easingwood, C. J., Edgett, S., Kleinschmidt, E. J., & Storey, C. (1994). What distinguishes the top performing new products in financial services. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11(4), 281-289.

- Damanpour, F., Walker, R. M., & Avellaneda, C. N. (2009). Combinative effects of innovation types and organizational performance: A longitudinal study of service organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 46(4), 650-675.

- Douglas, T. J., & Judge Jr, W. Q. (2001). Total quality management implementation and competitive advantage: The role of structural control and exploration. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 158-169.

- Drew, S. A. W. (1997). From knowledge to action: the impact of benchmarking on organizational performance. Long Range Planning, 30(3), 427-441.

- Eddleston, K. A., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2007). Destructive and productive family relationships: A stewardship theory perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(4), 545-565.

- Gioia, D. A. (1999). Practicability, paradigms, and problems in stakeholder theorizing. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 228-232.

- Goncalo, J. A. (2004). Past success and convergent thinking in groups: The role of group-focused attributions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34(4), 385-395.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., & Babin, B. J. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective: Pearson Education.

- Handler, W. C. (1989). Methodological issues and considerations in studying family businesses. Family Business Review, 2(3), 257-276.

- Henry, A. (2008). Understanding strategic management: Oxford University Press, USA.

- Hickman, C., & Raia, C. (2002). Incubating innovation. Journal of Business Strategy, 23(3), 14.

- Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, perceptions of effort--reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 287-302.

- Jon I. Martínez, Bernhard S. Stöhr, & Quiroga, B. F. (2007). Family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from public companies in Chile Family Business Review, 20(2), 83-94.

- Joshi, A., & Hanssens, D. M. (2010). The direct and indirect effects of advertising spending on firm value. Journal of Marketing, 74(1), 20-33.

- Kelly, L. M., Athanassiou, N., & Crittenden, W. F. (2000). Founder centrality and strategic behavior in the family-owned firm. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 25(2), 27-42.

- Klein, S. B., & Mühlebach, C. (2004). Customer-supplier relationships in the food industry: does family influence make a difference? Paper presented at the Family firms in the wind of change; FBN Research Forum Proceedings.

- Lam, A. (2006). Organizational innovation. In J. Fagerberg, D. C. Mowery & R. R. Nelson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of innovation (pp. 115-147): OUP Oxford.

- Lansberg, I., Perrow, E. L., & Rogolsky, S. (1988). Family business as an emerging field. Family Business Review, 1(1), 1-18.

- Lendel, V., & Varmus, M. (2011). Creation and implementation of the innovation strategy in the enterprise. Economics & Management, 16, 819-825.

- Litz, R. A., & Kleysen, R. F. (2001). Your old men shall dream dreams, your young men shall see visions: toward a theory of family firm innovation with help from the Brubeck family. Family Business Review, XIV(4).

- Lyman, A. R. (1991). Customer service: does family ownership make a difference? Family Business Review, 4(3), 303-324.

- Martínez, Bernhard, & Bernardo. (2007). Family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from public companies in Chile Family Business Review, 20(2), 83-94.

- Martins, E. C., & Terblanche, F. (2003). Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 6(1), 64.

- McConaugby, D. L., Matthews, C. H., & Fialko, A. S. (2001). Founding family controlled firms: performance, risk, and value. Journal of Small Business Management, 39(1), 31-49.

- Miller. (2003). Systems of organization: Taylor & Francis.

- Oswald, S. L., Muse, L. A., & Rutherford, M. W. (2009). The influence of large stake family control on performance: Is it agency or entrenchment? Journal of Small Business Management, 47(1), 116-135.

- Panuwatwanich, K., Stewart, R. A., & Mohamed, S. (2008). The role of climate for innovation in enhancing business performance: The case of design firms. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 15(5), 407-422.

- Poza, E. J. (2009). Family business: South Western Educ Pub.

- Rogers, M. (1998). The definition and measurement of innovation. Australia: Melbourne institute of applied economic and social research.

- Schulze, W. S., Lubatkin, M. H., Dino, R. N., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2001). Agency relationships in family firms: Theory and evidence. [Article]. Organization Science, 12(2), 99-116.

- Simosi, M., & Xenikou, A. (2010). The role of organizational culture in the relationship between leadership and organizational commitment: an empirical study in a Greek organization. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(10), 1598-1616.

- Tagiuri, R., & Davis, J. (1996). Bivalent attributes of the family firm. Family Business Review, 9(2), 199-208.

- Von Buch, S. D. (2006). The relationship of family influence, top management team's behavioral integration, and firm performance in German family businesses. Unpublished 3235871, Alliant International University, San Diego, United States -- California.

- Yener, M., & Akyol, S. (2009). Extent of family influence on family firm innovative behavior a study on small sized family firms in Istanbul. Journal of Global Strategic Management, 3(1), 103 -112.

- Zahra, S. A., Hayton, J. C., Neubaum, D. O., Dibrell, C., & Craig, J. (2008). Culture of family commitment and strategic flexibility: The moderating effect of stewardship. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 32(6), 1035-1054.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-016-7

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

17

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-471

Subjects

Business, management, behavioural management, macroeconomics, behavioural science, behavioural sales, behavioural marketing

Cite this article as:

Lok, S. Y. P., & Chong, W. Y. (2016). The Mediating Role of Innovation between Family Culture and Business Performance. In R. X. Thambusamy, M. Y. Minas, & Z. Bekirogullari (Eds.), Business & Economics - BE-ci 2016, vol 17. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 287-301). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.02.27