Abstract

The higher demands of halal food portray consumers’ feedback to fulfilling their religious requirements in food consumption, in which the burgeoning demands around the globe has sparked the industry players to plunge into this lucrative industry to bring in more economic growth and development to the country. Given the nature of the production of halal food is invisible to the eyes of consumers, thus it would lead to the unscrupulous of food producers to manipulate the halal procedures along the lines of food supply chain. Although halal governance at national level plays their significant roles to provide appropriate directives in the halal compliance among the halal industry players, however the roles of halal governance mechanisms at firm level are more crucial to ascertain that halal food integrity is always in place to protect the well-beings of Muslim consumers specifically. Hence, this study attempts to conceptually discuss on the issues of halal governance and halal governance structures at the firm level of the Malaysian Halal food industry which calls for deliberations based on halal food- and governance-related preceding studies in order to suit with the appropriate internal halal mechanisms of the Malaysian halal-certified food firms. Future research and ways forwards are further discussed therein.

Keywords: Halal, governance, Shariah, food Industry, SMEs

Introduction & Overview of Halal Governance

Halal industry plays an integral role in contributing major development and growth to the national economy and it is expected to bring the economy upwards with a lucrative amount of national revenues by 2030 as it is driven by a growing Muslim population all over the world and the increased purchasing power of Muslim consumers on food products. These market drivers have offered various economic opportunities for the food industry to thrive and tap into the international market. The existence of the halal business in the food industry is not only to fill in the market pie with economic-related aspects but implicitly to appease the social and religious obligations to society. Muslim consumers specifically are required to adhere to Islamic dietary laws that determine which foods are Halal (permissible) for Muslim consumption. However, as food chains are becoming more extensive and complex, Muslims are urged to be more attentive to their food contents (Bonne & Verbeke, 2006).

Although there is no restriction to plunge into the halal business regardless of the food producers’ religious background, it is important to note that our country’s business landscape is painted by the multi-racial nations resulting from the historical British colonization and foreign immigrants to the country. Therefore, the true comprehension of the halal concept may be misconstrued by non-Muslim food producers which could impair the integrity of halal food production and the reliability of Halal certification holders. Monitoring is a crucial issue in halal certification especially after securing the Halal certificate, where companies may be indifferent to comply with the halal requirements afterward (Matulidi et al., 2016a). In this regard, it is important to have strong and supportive governance at the firm level to monitor that food integrity is always in place and meets the religious requirements in food consumption among Muslims, especially in the post-pandemic phase to make the businesses stay afloat.

Given the mushrooming of halal businesses in the domestic market, the Malaysian government has taken various initiatives to strengthen and provide protection for the halal industry through the legislation of several halal- and food-related laws to regulate halal matters and monitoring halal activities among food companies at the national level. Among the food-and, halal-related laws enacted in the country include the Trade Descriptions Act 2011 (TDA 2011), Animal Act 1953 (revised 2006), Food Act 1983, Food Regulations 1985, Consumer Protection Act 1999, and the Local Government Act 1976. The TDA 2011 constitutes the central law regulating halal affairs in Malaysia, which came after the revision of the former revision in 1972 (TDA 1972) (Rahman et al., 2018; Zakaria & Ismail, 2014). The two laws underpinning the TDA 2011 are the Trade Description (Definition of Halal) Order 2011 and the Trade Description (Certification and Marking of Halal) Order 2011, which give a huge brunt to the compliance and implementation of halal practices among halal food producers.

At the national level, JAKIM is the sole government authority that is competent and responsible to govern and grant Halal certification to those eligible Halal applicant companies. From the supply perspective, JAKIM experiences some plights and challenges in carrying out its responsibility to monitor Halal activities towards food-producing companies as it lacks the appropriate number of staff, a processing procedures system, poor communication, and other halal monitoring matters which is perceived by companies as less efficient (Noordin et al., 2014). Given that halal businesses are mostly dominated by small-medium sized companies (SMEs), thus strong regulation on governance at the micro level among SMEs is still undermined as compared to what large counterparts have been required to adhere to the governance’s requirements and guidelines by the industry regulators (i.e., Security Commission, Bursa) through the issuance (with several revisions) of Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance (MCCG).

Although the governance of Malaysian public listed companies is highly regulated, however, there is no similar treatment has been given in the governance regulation among Halal SMEs although encouragement is made by the Securities Commission (SC) to embrace good governance (Rahim, 2017). Since the majority of Malaysian halal firms are involved in SMEs, SMEs are characterized by their flawed attributes, especially in the aspect of financial capability, staffing, and compliance (Htay & Salman, 2014). Nonetheless, major contributions of capital investments in both types of large and SME firms are funded by shareholders, and these firms are bound to the (conventional) governance with the presence of the board of directors (BODs) for the protection of the shareholders. Besides, given the additional guidelines for halal status by halal applicant firms, meticulous procedures of halal food production must be guided by the Shariah requirements with the appointment of executive staff or a special committee that are well-versed in halal affairs of the company, which so-called Halal executive and/or Internal Halal committee.

As far as halal business sustainability is concerned, the national Halal regulatory bodies which are JAKIM and Halal Development Corporation (HDC) play significant roles to strengthen the functions of the Internal halal executive/committee through the requirements in the latest revision of MS1500:2019 Halal Food-General Requirements and Malaysian Halal Management System 2020. These halal guidelines are designed to facilitate the implementation of halal compliance and procedures within the firm, which is meant for the issuance of halal certification by JAKIM for the applicant companies (Jais, 2019; Muhamed, 2020). Given that halal status gives positive remarks and impacts on the food business, thus securing and sustaining halal certification, especially during the post-pandemic phase is crucial to ascertain the survival of the food industry. In addition to the halal status in the food business practices, this implicitly bespeaks the functions of organizational governance of Halal food firms would have dual elements of conventional and halal governance which are essential for monitoring the compliance of halal general requirements in SMEs.

Since the features of SMEs are relatively different as compared to their large counterparts (listed companies), there might be less intensity on the domination of control over ownership which the governance structures of SMEs may comprise of combination synergy between the company’s management and board of directors. Since the application of halal status is subject to the discretion of the company, thus the composition of internal governance may vary across firms. In fact, the halal concept literally dictates that every food source(s), food preparation/process, and end food products must be consistent with the Shariah requirements and guidelines that are safe for human consumption. Thus, the appropriate internal governance structures for Halal food companies are very crucial at the firm level that entails the integration of Shariah and conventional governance framework to harmonize the halal governance at the firm (micro) level (Matulidi et al., 2016a; Matulidi et al., 2016b; Mohd Safian et al., 2020) to oversee the compliance of Halal standards is in place. Therefore, this study aims to conceptually discuss the issues of halal governance and halal governance structures at the firm level of the Malaysian Halal food industry which calls for deliberations based on halal food- and governance-related preceding studies.

Literature Review

Concept of governance and accountability theory

The concept of governance can be traced from its origin in Greek known as ‘kyberman’, which refers to ‘steer’, ‘guide’, or ‘govern’. Governance is generally can be defined as ‘the exercise of authority or control to manage a country’s affairs and resources’, ‘management of society’ and ‘complex system of interactions among structures, traditions, responsibilities, and practices to instill the main three key values of accountability, transparency, and participation within the organization (Punyaratabandhu, 2004). In other words, governance is about how business operations are monitored and overseen for the benefit of other people. Generally, governance refers to the changes in the role, structure, and operation process of the government, or the way social problems are resolved (Lada et al., 2009).

From the lens of Islam, governance is all about the obligations owed to the governor toward his/her wide range of constituents including suppliers, customers, competitors, employees, and even the community (Lewis, 2010). Islam perceives every human on earth as a person who holds responsibility and accountability to others or the so-called ‘. According to Beekun and Badawi (2005), the concept of (vicegerency) is fundamental for human existence and their ethical commitment based on Islamic teachings. The way a Muslim behaves as a vicegerent indicates he/she is performing an act of worship. The concept of worship is broad and applicable to all aspects of life (Beekun & Badawi, 2005) and has relation to an act of accountability. In other words, every human has a dual relationship with Allah () and other humans () as well on this earth which calls for his/her accountability (Lewis, 2010). Accountability holds its importance to the aspect of governance, especially in the context of the halal industry given that the halal context is bound into two overlapping aspects of compliance; legal and ethical principles. In this sense, Arjoon (2005) advocated that the functions of governance shall not only lay on legal compliance but also take into consideration ethical principles in order to deliver true, fair, and just, natural responsibilities and priorities to society. In this halal context, the theory of accountability attempts to explain the obligations of the food-producing firms’ governance mechanisms towards the community (umma) or society at large to behave and act according to the shari'a requirements especially in the food production process to provide assurance of its halal status.

The essence of the advent of halal governance is derived from the importance to address the issues of Halal certification. To obtain Halal certification, the applicant companies are bound to comply with the three main halal standards and guidelines (with the latest revision) are MS1500:2019 (3rd Rev): Halal Food – General Requirements, Malaysian Halal Management System (MHMS) 2020 (supersedes Guideline for Halal Assurance Management System in Halal Assurance System 2011) and Manual Procedure for Halal Certification (Domestic) 2020. The stability of the industry depends on strong well-established governance, including fully responsible boards, good Shariah governance, and relations with all the stakeholders. Toyyiban Management in the Halal Assurance Systems (HAS) framework tries to incorporate the elements of food safety, hygiene, and cleanliness along with the Shariah requirements (Jais, 2019). As far as the halal status of the food is concerned, Matulidi et al. (2016a) stated that there are three main components for halal governance in the Halal industry which include formulation, implementation, and regulatory functions; in which these three components implicitly imply the Halal governance is deployed to emphasize the function of halal governance at macro level (national/state) level. However, halal governance at the firm level (macro) level is crucial to ascertain the consistency in the compliance of Halal-related guidelines and standards in food production. Table 1 below depicts the previous studies on the internal halal governance mechanisms which are still limited in the current literature:

The above systematic literature review attempts to deliberate the extant studies on halal-related governance which most of the prior studies were undertaken almost five years ago in a conceptual setting. Besides, it is also very limited to find recent studies on the realm of governance, except for Mohd Safian, et al. (2020). In the existing studies which are in the conceptual setting, the discussion of halal governance is highlighted either solely on the national level of governance, or in-house halal governance. Meanwhile, for those studies which have been empirically performed, Matulidi et al. (2016) and Mohd Safian et al. (2020) have given emphasis solely on halal governance without addressing the other conventional component of governance which include the board of directors and Chief Executive Officer (CEO). The composition of the halal governance, which underpinnings by the conventional and Shariah requirements is indispensable in the lucrative halal industry, especially to monitor for the halal operational activities and simultaneously for the whole sustainability of the food business. The deliberation of the extant studies on the ideal criteria of the composition of an internal halal executive/committee within a firm is indeterminate, as what has been practiced in the large firms which are well-regulated by the market regulator. This might be due to the flawed attributes of the SMEs which are widely known for their limited financial capability and resources to emulate their large counterparts. Besides, the principles of the governance framework of halal food business may vary as compared to the large companies, since the emphasis is given more on the concept of halal status in every stage of the food supply chain. According to Mohd Safian et al. (2020), there are several essential components for the Halal corporate governance framework including Islamic accountability and responsibility, independence and objectivity, competency, confidentiality and commitment, consistency, Shariah audit and review, transparency and disclosure, corporate social responsibility and ethicality.

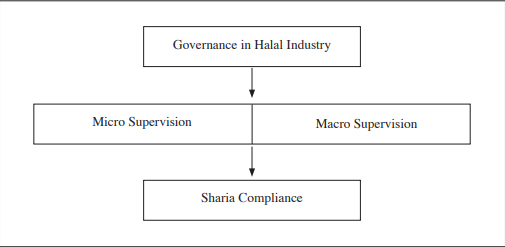

Nonetheless, as far as internal governance at the firm level is concerned, this study focuses on four components; Islamic accountability and responsibility, independency and objectivity, and competency and consistency. The framework in Figure 1 shows the involvement of halal agencies for monitoring and supervision in micro and macro level supervision. According to Matulidi et al. (2016a) and Noor and Noordin (2016), at macro-level supervision, it involves the supervision at the government level including JAKIM and HDC as well as at the state level which involves Jabatan/ Majlis Agama Islam Negeri (JAIN/MAIN) to monitor the whole involvement of halal supply chain activities in firm’s every stage from the beginning of production until reach to the hand of consumers. Meanwhile, the supervision at the micro level would involve the halal department within the halal food organization itself that is responsible to monitor its halal affairs and halal process along the halal food supply chain as suggested by the halal authorities/agencies which is known as Halal executive (in person) and internal Halal committee (IHC) (in an appointed committee). The appointment of a halal executive or executive that is well-versed in halal affairs of the company is important to ascertain that all the requirements as stated by JAKIM to secure or sustain for the Halal certification are fulfilled. Given the nature of SMEs being funded by a small number of shareholders, thus halal food SMEs may have dual types of governance; conventional and halal governance. The comparisons between conventional and halal governance are shown in Table 2, while Figure 1 below shows the conceptual framework of Halal governance in the Food industry at the macro vs micro level:

Source: Matulidi et al. (2016a)

Component of conventional governance

As stated in the latest version of MCCG 2021 in Principle A – Board leadership and effectiveness, the guidelines are provided on addressing the duties and responsibilities of the board including the board of directors, chairman, chief executive officer (CEO), and appointed board committees (audit committee, nomination committee, and remuneration committee) to be discharged for meeting the companies’ goals and objectives. The guidelines also encourage the responsibilities of the board to work closely with top management. This guidance is mainly intended for large (listed) companies to abide by in order to promote sustainability and restore confidence among the companies’ investors. However, SMEs are encouraged to comply with the guidelines, and it is subject to their discretion to do so given the unlisted nature of SMEs to implement the recommendations.

Component of halal governance

The component of Halal governance may be different from the existing conventional governance as stipulated by the SC mainly for listed companies, as the composition of halal governance is intended to oversee the halal procedures and implementation by the management of halal-food-producing companies. Halal governance involves three main components which are formulation, regulation, and implementation the first two components relate to halal governance at the national level ecosystem, while the latter relates more to the halal governance execution at the firm level (Matulidi et al., 2016a). Likewise, Mohd Safian, et al. (2020) also advocated that the internal governance mechanism involves more on Halal monitoring, controlling, improving, and preventing any non-compliance with Halal-related guidelines and requirements. Since this study mainly focuses on internal halal governance, there are four categories of internal governance mechanisms as approached by the competent national authority (JAKIM) and Department of Standards (DOS) based on the size of companies – multinational, medium, small and micro companies which include the appointment of Halal executive, internal Halal committee, the appointment of minimum two Muslim workers with Malaysia citizenship status (full-time post) and establishment of Halal Assurance System or internal halal control system (Muhamed, 2020). The following Table 2 shows the key responsibilities and appointment requirements based on the respective source of reference (across firm size):

Research Methodology

Since this study is a conceptual type in nature, thus this study employs the review of several prior kinds of literature relating to the legislation of laws and regulations on halal matters, corporate governance, and halal governance. As far as halal governance at the firm level is concerned, the deliberations of the current presence and recommendations made by the Halal guidelines and standards on internal halal mechanisms are delivered through the systematic literature review (SLR). Given there are broad sub-sectors underpinning the Halal industry, however, this study mainly focuses on the internal governance mechanisms in the food sector, regardless of the size of companies as per mentioned in the Manual procedure of the Halal Assurance System (HAS).

Conclusions and Way Forward

This study aims to review the extant studies on halal governance by conceptually addresses on the issues of internal governance mechanisms at the firm level in the Halal food industry, given that the primary reliance on external halal governance is to monitor the compliance of halal requirements in food production led by the government authorities and agencies towards food producers seems is no longer appropriate. The plausible reasons behind the importance of having internal halal governance are due to lack of proper halal policy, lack of expertise and lack of an adequate number of staff, and lack of capability to monitor the compliance practices from the ground at the firm level, which makes the authorities find difficult to prove if a food producer adheres to halal requirements in food production (Matulidi et al., 2016a). Based on the review of the previous literature, most of the prior studies on internal halal governance are carried out based on the conceptual study, and only a handful of the studies are performed empirically. It is important to note that internal halal governance has no strong directives by the competent authority as compared to corporate governance which is well-governed for the implementation among the listed companies by the industry regulators.

Besides, although there are guidelines on the internal halal governance mechanisms for food producers to abide by as stated in the main halal standards and guidelines such as MS1500:2019 (3rd Rev): Halal Food – General Requirements, Malaysian Halal Management System (MHMS) 2020 (supersedes Guideline for Halal Assurance Management System in Halal Assurance System 2011) and Manual Procedure for Halal Certification (Domestic) 2020, however, such compliance is subject to the discretion by food-producing SMEs, which is characterised by their flaw attributes especially in the financial aspect, as their main objective is to secure for Halal-certified status. Given the pandemic-stricken food companies which might experience huge challenges to weather the business survivability during the pandemic, thus strategic monitoring of food integrity is very crucial. Although this study is undertaken conceptually, however, there are still loopholes in the existing studies to address the in-house governance, especially in the context of gastronomy. Thus, this is not surprising to know that the existing studies pertaining to internal governance mechanisms in the halal food industry are still limited which warrants future studies to be conducted in an empirical setting, in a way to investigate the compliance of the composition and presence of halal governance mechanisms at the firm level. Thus, this could assist to strengthen and spur the growth and development of the halal food industry, nationally and globally.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Universiti Tenaga Nasional’s Institute of Research Management Centre (iRMC) for the funding support to conduct the study under POCKET Grant No. J510050002/P202211.

References

Arjoon, S. (2005). Corporate Governance: An Ethical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 61, 343-352.

Beekun, R. I., & Badawi, J. A. (2005). Balancing ethical responsibility among multiple organizational stakeholder: Islamic perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 60, 131-145.

Bonne, K., & Verbeke, W. (2006). Muslim consumer’s motivations towards meat consumption in Belgium: qualitative exploratory insights from means-end chain analysis. Anthropology of Food, 5(5), 1-24.

Htay, S. N. N., & Salman, S. A. (2014). Proposed best practices of financial information disclosure for zakat institutions: A case study of Malaysia. World Applied Sciences Journal, 30(30), 288-294.

Jais, A. S. (2019). Halal executive as part of the Malaysian Halal Certification Requirements. How Did it all begin? Halal Note Series- Halal Common No. 4, 1-2.

Lada, S., Tanakinjal, G. H., & Amin, H. (2009). Predicting intention to choose halal products using the theory of reasoned action. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 2(1) 66-76.

Lewis, M. K. (2010). Accentuating the positive: governance of Islamic investment funds. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 1(1), 42-59.

Matulidi, N., Jaafar, H. S., & Bakar, A. H. (2016a). The Needs of Systematic Governance for Halal Supply Chain Industry: Issues and Challenges. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences, 40-46.

Matulidi, N., Jaafar, H. S., & Bakar, A. H. (2016b). Halal Governance in Malaysia. Journal of Business Management and Accounting, 6(2), 73-89.

Mohd Safian, Y. H., Salleh, A. Z., Jamaluddin, M. A., & Jamil, M. H. (2020). Halal Governance in Malaysian Companies. Journal of Fatwa Management and Research, 20(1), 40-52.

Muhamed, N. A. (2020). Halal Industry and Certification and Governance: JAKIM Requirements. In N. A. Muhamed, H. Yaacob, & N. Muhamad (Eds.), Halal Governance and Management: Malaysian and Asian Countries (pp. 128-141). USIM Press

Noor, N. L. M., & Noordin, N. (2016). A Halal Governance Structure: Towards a Halal Certification Market. In S. Ab. Manan, F. Abd Rahman, & M. Sahri (Eds.), Contemporary Issues and Development in the Global Halal Industry (pp. 153-164). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1452-9_14

Noordin, N., Md Noor, N. L., & Samicho, Z. (2014). Strategic Approach to Halal Certification System: AN Ecosystem Perspective. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 121, 79-95.

Punyaratabandhu, S. (2004). Commitment to good governance, development and poverty reduction: Methodological issues in the evaluation of progress at the national and local levels. CDP Background Paper No. 4 ST/ESA/2004/CDP/4, United Nations Development Policy and Analysis Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Rahman, A. A., Md Ismail, C. T., & Abdullah, A. N. (2018). Regulating halal food consumption: Malaysian scenario. International Journal of Law, Government and Communication, 3(13), 313-321.

Rahim, N.@ F. (2017) Bridging Halal Industry and Islamic Finance: Conceptual Review on the Internal Governance. In Social Sciences Postgraduate International Seminar (SSPIS) 2017 (pp. 731-738). School of Social Sciences, USM, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia.

Saad, S. N. H., Abd Rahman, F., & Muhammad, A. (2016). An overview of the shariah governance of the halal industry in Malaysia: with special reference to the halal logistics. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences, 6, 53-58.

Zakaria, A., & Ismail, S. Z. (2014). The Trade Description Act 2011: Regulating Halal in Malaysia. In International Conference on Law, Management and Humanities (ICLMH'14), 21-22 June 2014, Bangkok, Thailand (pp. 8-10).

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

18 August 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-963-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1050

Subjects

Multi-disciplinary, Accounting, Finance, Economics, Business Management, Marketing, Entrepreneurship, Social Studies

Cite this article as:

Anis Ramli, J., Aishah Hashim, H., & Salleh, Z. (2023). Governance of Malaysian Halal Food Industry: Conventional Governance vs Shariah Requirements. In A. H. Jaaffar, S. Buniamin, N. R. A. Rahman, N. S. Othman, N. Mohammad, S. Kasavan, N. E. A. B. Mohamad, Z. M. Saad, F. A. Ghani, & N. I. N. Redzuan (Eds.), Accelerating Transformation towards Sustainable and Resilient Business: Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Crisis, vol 1. European Proceedings of Finance and Economics (pp. 83-94). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epfe.23081.8