Abstract

Body shaming is the act of saying something negative about one's own body or about another person's body. The aim of this research was to identify the predisposition of high school students in grades IX and X to body shaming, as a form of bullying and cyberbullying, through the use of digital technologies. The present study examined the propensity of young participants in bodyshaming research between April and May 2021. The method used was a sociological survey based on a questionnaire. The study was conducted with 1967 students from 15 different high schools in Caras-Severin County (Romania). The average age of the students included in the research was 16 years, 56.5% being female, 42.4 male, and 1.1% refused to specify their gender. The data was collected through an online questionnaire. The results obtained consisted in building a score that highlights the trend towards cyberbullying and body shaming, a score built on the significance of specific situations in which body shaming can manifest. The data obtained during the research show that the score regarding the tendency of high school students towards cyberbullying and body shaming differs depending on the gender of the respondents, the boys registering much higher scores of cyberbullying and body shaming, compared to their female colleagues.

Keywords: Body shaming, cyberbullying, teenagers

Introduction

The physical element symbolizes the version of ourselves that we portray to other people and to society. The extensive promotion of aesthetic standards about the physical appearance of the human body may lead to feelings of inadequacy or victimization among those who do not fulfil these standards. Adolescents (particularly adolescent females) are exceptionally susceptible to negative feedback from others (Bearman et al., 2006).

Adolescence is accompanied by numerous and profound changes in biological, physical, mental, moral, social, etc. terms, as it is the period during which the characteristics of childhood fade against the backdrop of the intensification of specific individual psychic transformations and manifestations that facilitate the transition to the next stage of development. At the same time, adolescence is a period of life characterized by searches, discoveries, knowledge of one's own identity and that of others, and of society with its norms, patterns, and required standards. Among adolescent females, the effect of body image is significantly more pronounced. They are much more susceptible to peers' negative comments regarding their physical appearance (Frisén et al., 2008; Menzel et al., 2010). However, research indicates that there are adolescents who, despite experiencing unfavorable interactions about their physical appearance, do not develop body image issues.

During adolescence, adolescents devote ever increasing attention to their personal growth and to the characteristics that distinguish them from others. Particularly among girls, body image dissatisfaction increases with the advent of adolescence (Bucchianeri et al., 2013; Cusumano & Thompson, 2001; Thompson et al., 1999)

Physical development during puberty, which controls the accentuation of the human body's curves and favors the deposition of fat in some places of the body, often conflicts with socially sanctioned criteria of physical attractiveness. In this context, an increasing number of adolescent girls are dissatisfied with their physical appearance (Ricciardelli et al., 2003), with some making significant efforts to eliminate what displeases them and thus approach the social representation of the ideal female appearance (Allen & Land, 1999; Gilbert & Irons, 2009).

Many teenagers (particularly from Western cultures) believe that body image determines social outcomes, such as a person's beauty, power, success, and popularity (Duarte et al., 2017; Pinto-Gouveia et al., 2014), as well as their feeling of security and self-esteem (Gilbert, 1997; Kurzban & Leary, 2001). Body image is a real determinant of social attractiveness for many individuals. A beautiful, harmonious physique that conforms to the criteria socially promoted and prized by others, along with an acceptable mindset, may boost a person's chances of receiving social approval. In contrast, the absence of some features/physical aspects valued by society or the presence of some characteristics/aspects that others may perceive as physical defects affects self-esteem and self-confidence, contributing to the emergence and amplification of feelings of inferiority, shame, and guilt, which are frequently maintained and developed through interactions with others.

Problem Statement

The social emotion of shame is complicated and self-centered. It is characterized by negative self-evaluations such as being inferior or flawed, being judged or criticized by others, and being exposed to social exclusion, rejection, or even attacks from others (Duarte et al., 2017; Tracy & Robins, 2004). Shame about one's body image has deep roots and is related to ideal standards of bodily beauty (Lestari, 2019). According to Fredrickson and Roberts (1997), body shame is a form of evaluating one's own and others' physical appearance in relation to internalized standards of ideal beauty.

Irons and Gilbert (2005) found that teenagers are especially sensitive to social messages and cues about what is attractive and acceptable in their group. Adolescents' tendency to detach themselves from their parents, as the main attachment figures, orients them more and more towards their peer group, becoming extremely receptive to the signals and messages transmitted verbally, nonverbally, and/or paraverbally by them (Allen & Land, 1999). In this phase of development, adolescents pay special attention to the highlighting of socially valued features and try to camouflage as much as possible the contrasting aspects with the standards of the group to which they belong. At the same time, fears of rejection, disapproval, or potential attacks from the peer group intensify (Gilbert & Irons, 2009). Teenagers who have bodies that differ greatly from ideal beauty standards sometimes feel ashamed and unsure of being accepted by their social group (Libing et al., 2021).

Negative self-evaluations as well as the subject's beliefs that others consider him unattractive or undesirable because of his physical appearance can generate feelings of shame towards his body image (Gilbert, 2002). The feedback received from others permanently shapes one's own perceptions of body image, building either a positive self-image when the person feels validated, appreciated, included, and accepted by others, or a negative self-image when one feels devalued, bullied, guilty, ignored, and/or excluded by others.

Cyberbullying can be defined as an aggressive, repetitive act carried out by using electronic means of communication, individually or in a group, against a victim who cannot easily defend themselves, with the intentional aim of harming them (Smith et al., 2008). Bullying and cyberbullying, of which a number of adolescents are victims, is often focused on physical appearance, especially among adolescent girls (Frisén et al., 2008; Menzel et al., 2010). Even in cases where bullying is not fueled by aspects related to body image, according to research in the field, the experience of victimization is often associated with perceptions of unattractiveness and inferiority (Duarte et al., 2015; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 1999; Matos et al., 2014).

Body shaming is one of the common forms of bullying and/or cyberbullying. The phenomenon of bullying and cyberbullying, respectively, body shaming experiences, are ubiquitous in adolescence (Nansel et al., 2001), but their impact on the mental health of adolescents can be different from case to case. Research in the field (Cunha et al., 2012; Gilbert & Irons, 2009; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 1999) shows that adolescents' experiences as victims of bullying, cyberbullying, and body shaming affect their general health, especially mental health, generating a series of difficulties, including those related to their body image.

Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to address the following research question:

In the 9th and 10th grade classes of Caraş-Severin (Romania) do adolescents indicate body shaming behaviors?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this research was to determine the propensity of ninth- and tenth-grade students to participate in body shaming via the use of digital technologies.

Research Methods

The research is part of a wider study undertaken in conjunction with students at the University of Turin (Italia) and led by Professor Renato Grimaldi between March 2021 and June 2021, when data were gathered from Romanian and Italian teenagers.

In this paper, only Romanian group findings will be discussed, meaning that data comparing Romania and Italy will be discussed in the future.

The investigated population – the sample structure

In the research, 1965 teenagers from grades IX and X were randomly selected from 27 schools in the Caraş-Severin area of Romania. 57.54% are female, 42.39% are male, and 1.07% choose to remain anonymous. The tables 1–3 illustrate the organization of the experiment depending on the grade level examined, the kind of experiment, and the age of the participants.

Research methodology

A sociological survey based on a questionnaire was used as the methodology. Based on the responses to the questionnaire, it was possible to determine the respondents' propensity for body shaming by gauging their level of agreement or disagreement with a variety of real instances. The questionnaire items were designed to describe concrete situations susceptible to body shaming, and the adolescents who participated in the study indicated their level of agreement on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates total disagreement and 5 indicates total agreement with the proposed statements.

Findings

The interpretation of the study outcomes will be dependent on certain questionnaire questions.

Item: A person who is overweight should not publish images of oneself in a swimsuit on social media.

As shown by the data in Table 4, most respondents (50.94%) strongly disagree with the statement that an overweight person should avoid sharing images of himself in a swimsuit on social networks. However, 14.44% of respondents fully agree with this statement, which may indicate that these individuals have a significant propensity for body shaming. In addition, the recommendation that overweight individuals avoid sharing photos of themselves in swimsuits might be seen by some responders as an effort to shield overweight individuals from potential criticism or even acts of body shaming.

: When a colleague's physical attractiveness is criticized on the Internet, I feel sad for him.

A The majority of adolescents who participated in our study (71,91% - Table 5) demonstrate a high level of empathy when they indicate entire agreement with the preceding statement. In contrast, 7.23 percent of adolescents look indifferent when their friends are insulted based on their physical appearance.

Empathy is the capacity to comprehend and absorb the emotional condition of another individual (Stavrinides et al., 2010). According to the research, there is a negative association between empathy and violence (Endresen & Olweus, 2001; Gini et al., 2007). Also, research on bullying indicate that kid aggressors lack empathy for their victims, indicating a negative association between empathy, defined as children's capacity to understand how another person feels, and bullying, i.e. with the child's propensity to bully others (Olweus, 1993; Stavrinides et al., 2010). Cyberbullies exhibited less empathic reactivity than non-cyberbullies, according to a research involving 2,070 pupils from secondary schools in Luxembourg. (Steffgen et al., 2011, p. 643).

It is far less severe to offend a coworker online for the way they dress than it is to do so face-to-face.

Utilizing modern tools, the preceding piece investigates adolescents' propensity for body shaming. In contrast to the previous item, in Table 6 we observe a doubling of the percentage of adolescents who express total agreement with this statement (15.01%), which suggests that they may be willing to engage in body shaming cyberbullying if given the chance, given that they view such acts as less serious than face-to-face bullying. The rising use of the Internet and digital communication platforms has enabled the creation and growth of cyberbullying, as described in the literature (Ispas & Ispas, 2021). Cyberbullying often has considerably more severe repercussions than traditional bullying. owing to the fact that electronic gadgets constantly alert and download material from social networks and other websites (Tanrıkulu et al., 2015).

When a colleague's physical attractiveness is criticized on the Internet, I feel sad for him.

23.66% (Table 7) believe that those who do not fulfill particular beauty criteria should be excluded from social organizations, while 62.34% feel that this practice is incorrect. The fact that over a quarter of the kids polled express strong feelings about the conditional admittance in social groups based on particular aesthetic standards demonstrates that for them, physical beauty remains a sensitive topic that may be used to weave or obstruct interpersonal bonds.

: If you post images of your physical faults online, you must accept any and all feedback (you can’t to complain).

The preceding item relates to the assumption of persons with aggressive tendencies that victims embrace their position as victims, i.e., suffer in silence if others make cruel remarks based on the photographs they upload of themselves. The views of teens responding to this item are mixed, with the highest score (31.7% - Table 8) being recorded at level 5 of the scale, i.e. total agreement, which may imply that they are in favor of accepting responsibility for the consequences of posting images that reveal his physical faults. At the other end of the spectrum, 25.04% of respondents allow space for humanistic principles, demonstrating their entire disagreement with the scenario outlined in this item (Table 8).

: It is inappropriate to invite others to engage in online Challenges that put their bodies through rigorous testing.

The majority of responses (45.65% - Table 9) indicate the complete consent of the adolescents participating in the study about the invitation of others to engage in online Challenges that put their bodies to rigorous tests. The responses indicate that a significant proportion of teenagers recognize the high degree of risk involved in participating in those online challenges in which the human body is subjected to strenuous tests and, as a result, exercise caution in relation to them; therefore, considering them to be a request of this nature addressed to others is incorrect.

: It might be entertaining to put someone in an embarrassing position in order to capture a picture or video of them and then upload it to the internet.

The item has the lowest score (2.75% - Table 10) for level 4 of the scale and the fifth-highest score (5.6%) for level 5 indicating complete agreement with a deliberate scenario of bullying and cyberbullying. Practically all of these adolescents have genuine worries about bullying and cyberbullying. Motivated by the desire to entertain themselves at others' expense, they create humiliating circumstances for others, which may subsequently be utilized as cyberbullying. The majority of adolescents (72.32%) reject fiercely the notion of seeing a possible act of cyberbullying in a humorous light (Table 10).

Even though everyone does it, it is inappropriate to call out a person's physical faults in a picture or video.

Even if everyone does it, highlighting a person's physical flaws beneath a picture or video is improper, according to the majority of replies (59.24% - Table 11) from teens. In contrast, 15.42% of teens express absolute disagreement with the circumstances provided in the preceding item, indicating that they believe it is perfectly OK to emphasize a person's shortcomings beneath a picture (i.e., to engage in body shaming), particularly if "everyone does it."

If someone receives a meme concerning a physical condition, they are not required to pay attention to it since it is only a meme.

Often, the inclination to minimize the severity of an act of body shaming might be seen as a technique for coping with the act's consequences. Most of the time, it is simple to say but difficult to execute, particularly if the related memes do not refer to you directly.

Teenagers may cope with body-shaming events by downplaying the significance of the specific meme, employing humor, or engaging in self-irony. It is conceivable that this was also the view of the 45.65% of adolescents (Table 12) who selected level 5 on the scale for this item, so expressing their complete agreement with the scenario provided in the item. On the other end of the spectrum, 11.4% of the adolescents (Table 12) who participated in the study strongly disagreed with the recommendation to disregard a meme concerning a physical disability and consider it harmless. The concern of teens that such occurrences (getting memes about physical faults) would be repeated constantly in the absence of a solid attitude of unequivocal rejection of them, making them hard to accept or ignore, is concealed behind this abrasive attitude.

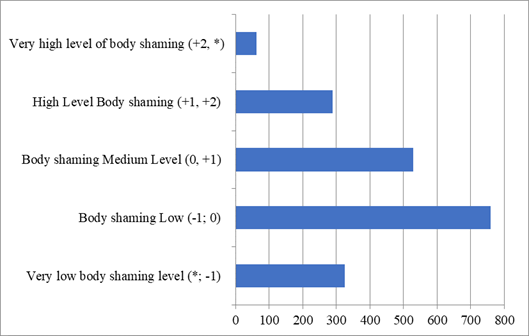

The frequency distribution of the standardized body shaming propensity score was determined by analyzing all the data collected from the 1965 adolescents from Romania who participated in the study. The level classes were established using a standard deviation of 1 as the basis (Table 13, Figure 1).

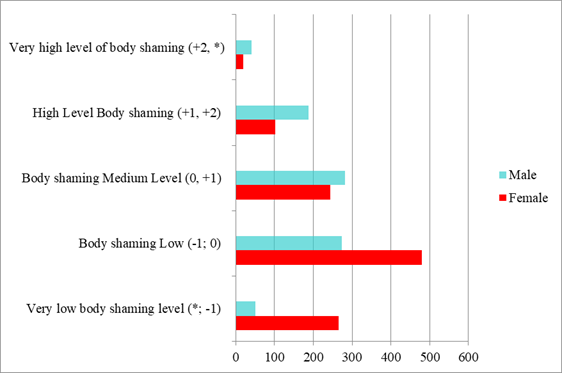

Regarding the frequency distribution of the standard body shaming propensity score by gender among the 1944 teenagers (1111 females and 833 males) who stated their gender, the following statistics are reported in Table 14, Figure 2 and Table 15.

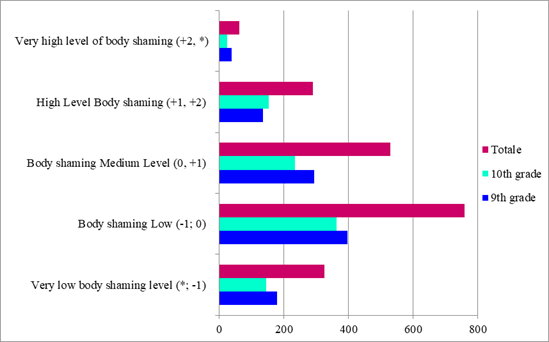

Table 16, Figure 3 and Table 17 indicate the frequency distribution of the standard score for propensity to body shaming based on the class of teenagers who participated in the study.

Conclusion

When adolescents approach adolescence, they spend a growing amount of attention not just on aspects of their life related to their own development, but also on features that distinguish them from others. Body shaming refers to the act or practice of disparaging or making fun of someone based on their physical appearance. The passage of time has resulted in a variety of beauty standards being established by society. Historically, body shaming has been intended towards persons who do not correspond to the commonly accepted standards of physical attractiveness. The present study collected and examined the answers of 1965 teenagers from the Romanian county of Caraş-Severin in order to identify their propensities for body shaming via the use of digital technologies. The replies of these teenagers were gathered and studied by the researchers, who questioned them about particular scenarios that fell under the scope of body shaming practices. In light of the data, it seems that males are more likely than females to participate in body shaming (1.8% vs. 4.92%), as shown by their score on the former. In terms of distribution by grade, ninth-graders exhibited a larger incidence of body shaming (3.6%), compared to their tenth-grade counterparts (2.6%). Teenage body shaming may lead to a number of mental health problems, including eating disorders, anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, among others.

References

Allen, J. P., & Land, D. (1999). Attachment in adolescence. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment theory and research. Guilford.

Bearman, S. K., Presnell, K., Martinez, E., & Stice, E. (2006). The skinny on body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. Journal of youth and adolescence, 35(2), 217-229. DOI:

Bucchianeri, M. M., Arikian, A. J., Hannan, P. J., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Body dissatisfaction from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Body image, 10(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.09.001

Cunha, M., Matos, M., Faria, D., & Zagalo, S. (2012). Shame memories and psychopathology in adolescence: The mediator effect of shame. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 12(2), 203-218. https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen12/num2/327/shame-memories-and-psychopathology-in-adolescence-EN.pdf

Cusumano, D. L., & Thompson, J. K. (2001). Media influence and body image in 8–11-year old boys and girls: A preliminary report on the multidimensional media influence scale. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(1), 37-44. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1<37::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-g

Duarte, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Stubbs, R. J. (2017). The prospective associations between bullying experiences, body image shame and disordered eating in a sample of adolescent girls. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 319-325. DOI:

Duarte, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Ferreira, C., & Batista, D. (2015). Body Image as a Source of Shame: A New Measure for the Assessment of the Multifaceted Nature of Body Image Shame: A New Measure for the Assessment of Body Image Shame. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(6), 656-666. DOI:

Endresen, I. M., & Olweus, D. (2001). Self-reported empathy in Norwegian adolescents: Sex differences, age trends, and relationship to bullying. In A. C. Bohart, & D. J. Stipek (Eds.), Constructive & destructive behavior: Implications for family, school, & society, American Psychological Association (pp. 147–165). DOI:

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women's Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. DOI:

Frisén, A., Holmqvist, K., & Orcarsson, D. (2008). 13–year-olds’ perception of bullying: definitions, reasons for victimisation and experience of adults’ response. Educational Studies, 34(2), 105-117. DOI:

Gilbert, P. (1997). The evolution of social attractiveness and its role in shame, humiliation, guilt and therapy. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70(2), 113-147. DOI:

Gilbert, P. (2002). Body shame: A biopsychosocial conceptualisation and overview with treatment implications. In P. Gilbert, & J. Miles (Eds.), Body shame: Conceptualisation, research and treatment (pp. 3-54). Brunner Routledge.

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2009). Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. In Allen, N. (Ed.), Psychopathology in adolescence. Cambridge University Press.

Gini, G., Albiero, P., Benelli, B., & Altoè, G. (2007). Does empathy predict adolescents' bullying and defending behavior? Aggressive Behavior, 33(5), 467-476. DOI: 10.1002/ab.20204

Irons, C., & Gilbert, P. (2005). Evolved mechanisms in adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms: The role of the attachment and social rank systems. Journal of Adolescence, 28(3), 325-341. DOI:

Ispas, C., & Ispas, A. M. E. (2021). Perceptions and Challenges Regarding Cyberbullying during the Covid-19 Pandemic, Educația 21 Journal, 21, 158-167. DOI: 10.24193/ed21.2021.21.16

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rissanen, A., Rimpela, M., & Rantanen, P. (1999). Bulimia and bulimic behaviour in middle adolescence: More common than thought? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 100(1), 33–39. DOI:

Kurzban, R., & Leary, M. R. (2001). Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: The functions of social exclusion. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 187-208. DOI:

Lestari, S. (2019). Bullying or Body Shaming? Young Women in Patient Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Philanthrophy Journal of Psychology, 3(1), 59-66.

Libing, V., Lerik, M. D. C., & Kiling, I. Y. (2021). The Experience as a Victim of Bullying and Body Image Perception in Adolescents. Journal of Health and Behavioral Science, 3(1), 58-68. DOI: 10.35508/jhbs.v3i1.3132

Matos, M., Ferreira, C., Duarte, C., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2014). Eating disorders: When social rank perceptions are shaped by early shame experiences. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory research and practice, 88(1), 38-53. DOI:

Menzel, J. E., Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Mayhew, L. L., Brannick, M. T., & Thompson, J. K. (2010). Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image, 7(4), 261−270. DOI:

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying Behaviors Among US Youth: Prevalence and Association With Psychosocial Adjustment. JAMA, 285(16), 2094. DOI:

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell.

Pinto-Gouveia, J., Ferreira, C., & Duarte, C. (2014). Thinness in the Pursuit for Social Safeness: An Integrative Model of Social Rank Mentality to Explain Eating Psychopathology: Thinness in the Pursuit for Social Safeness. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(2), 154-165. DOI:

Ricciardelli, L. A., McCabe, M. P., Holt, K. E., & Finemore, J. (2003). A biopsychosocial model for understanding body image and body change strategies among children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24(4), 475-495. DOI:

Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 376-385. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

Stavrinides, P., Georgiou, S., & Theofanous, V. (2010). Bullying and empathy: a short-term longitudinal investigation. Educational Psychology, 30(7), 793-802. DOI:

Steffgen, G., König, A., Pfetsch, J., & Melzer, A. (2011). Are Cyberbullies Less Empathic? Adolescents' Cyberbullying Behavior and Empathic Responsiveness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(11), 643-648. DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0445

Tanrıkulu, T., Kınay, H., & Arıcak, O. T. (2015). Sensibility Development Program against Cyberbullying New Media & Society, 17(5), 708-719. DOI:

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L., Altabe, M., & Tanleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). TARGET ARTICLE: "Putting the Self Into Self-Conscious Emotions: A Theoretical Model". Psychological Inquiry, 15(2), 103-125. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 May 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-962-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

6

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-710

Subjects

Education, reflection, development

Cite this article as:

Ispas, C., & Eugenia Ispas, A. (2023). The Predisposition of Teenagers from the First High School Classes to Body Shaming. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2022, vol 6. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 561-574). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23056.51