Abstract

Resilience is a key point in the current educational policies. Throughout this study, we aimed to take a step forward in defining and describing a resilient educational climate, starting from the learning barriers that need to be overcomed. We qualitatively and quantitatively analysed the learning barriers identified by pre-university teachers through a questionnaire-based survey. From the primary lexical analysis of the data, we found that students' and their families' lack of interest in school is the main threat to school learning from the perspective of pre-university teachers. This highlights the discrepancy between the educational offer and the needs of the beneficiaries of educational services. However, we coded responses from N=110 participants - pre-university teachers and found that the most common type of learning barrier mentioned by them was digital distractions. This may raise questions about teachers' openness to the digitisation of the educational process, since they perceive digital devices as a barrier to learning. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the effect of learning barriers on the resilient educational climate. There were no statistically significant differences in the means of the resilient educational climate between categories of learning barriers.

Keywords: Educational climate, learning barriers, resilience, resilient educational climate

Introduction

Motto: If you define the problem correctly, you almost have the solution.” (Steve Jobs).

In the field of educational sciences, epistemic interest in learning has increased significantly with the paradigmatic shift from education focused on teaching and content to education cantered on the learner and his/her specific learning and development needs. Therefore, human learning has soon become the subject of numerous theoretical and empirical works of value for educational practice.

Learning is an "integrative, complex, multidimensional and dynamic concept, with plurivalent psycho-pedagogical meanings" (Bocoș et al., 2016a, p. 140). Therefore, there is no single explanatory model of the concept, but we find numerous learning theories that consider this process from different perspectives. We only mention the main schools of thought that have highlighted some defining aspects of human learning: behaviourism defines learning in terms of behavioral changes, developmental theories refer to the developmental stages and stadiality of learning, humanistic theories emphasize personal needs and interests, and cognitive theorists approach learning from the perspective of cognitive and metacognitive processes (Dierking, 1991; Metcalf et al., 2016).

In this paper, we will approach the learning process from a cognitivist perspective, defining it as "a series of sequential operations referred to as information processing" (Dierking, 1991, p. 4). In this case, learning is seen as a linear process composed of a sequence of cognitive actions involved in processing information and environmental stimuli: attention, perception, encoding, memory, transfer, thinking, language, etc., but with the involvement of the person's emotional system. This sequence of mental operations can be interrupted or blocked by various factors. We will generally call these disruptive factors: learning barriers.

In the literature, we have identified several examples of barriers or obstacles that may occur in the learning process in specific contexts, such as inclusive education, distance education or online education (Forde & OBrien, 2022; Nurjanah, 2022). However, we have not identified a taxonomy of learning barriers, i. e. of those elements within the learning situation and the learning context that represent impediments for the learning process. For this reason, we are proposing a brief own-conception classification of these barriers based on their nature:

- Emotional barriers (e.g. low self-esteem, fear of mistakes, anxiety, etc.)

- Cognitive barriers (e.g. memory difficulties, attention deficit, lack of cognitive stimulation, learning difficulties, learning disabilities, etc.)

- Barriers related to curricular adaptation (e.g. content taught is too difficult, requirements/ homework too difficult, etc.)

- Social barriers (e.g. bullying, peer pressure, entourage, etc.)

- Family barriers (e.g. disadvantaged environment, parental divorce, lack of parental interest, etc.)

- Medical barriers (e.g. disability, medical problems, special educational needs, etc.)

- Contextual barriers (e.g. learner's current state/mood, learner's level of fatigue, elements related to the physical environment in which learning takes place: noise, inappropriate temperature or lighting, etc.).

The aim of this classification is to provide teachers with a more structured view of the factors that can disrupt students’ learning, and consequently enable them to provide targeted and effective intervention where they identify problems. Learning barriers may occur and may be surmounted in both formal and non-formal education, in curricular as well as extra-curricular activities.

Problem Statement

Today's changing, unstable and uncertain society requires significant changes and new directions in educational policies and practices. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has proposed a new learning framework for the year 2030 described through the metaphor. The key point of this new education policy is: the creation of diverse formal and non-formal learning contexts in which learners can develop skills, knowledge, attitudes, abilities and values, leading to the well-being of society as a shared destination:

The metaphor of a learning compass was adopted to emphasise the need for students to learn to navigate by themselves through unfamiliar contexts, and find their direction in a meaningful and responsible way, instead of simply receiving fixed instructions or directions from their teachers (OECD, 2019, p. 24).

Orienteering in unfamiliar contexts involves exposure to a number of risks. Therefore, in tandem with this new educational orientation, it is necessary to promote resilient attitudes among learners.

Following the framework already mentioned, the OECD (2021) introduces and emphasises the importance of resilience in the field of education. According to this report, children "are experiencing more change than ever before" and their future is unpredictable, which explains the need for resilience at the level of learners, the educational environment and the entire educational system.

By resilience, in a broad sense, we refer to an individual's ability to overcome risky situations, difficulties or unpleasant experiences and to thrive regardless, using inner strengths and/or supported by significant persons called resilience mentors (Bocoș et al., 2019; Greitens, 2020; Ionescu, 2013; Levine, 2022). Due to the multitude of definitions for this concept and the multiple domains of applicability, we have identified three complementary explanatory models of resilience: resilience as a personality trait that manifests in the presence of risk, resilience as a process of adaptation and overcoming adversity, and resilience as an outcome of the adaptive process of overcoming an obstacle (Verdeș & Baciu, 2022). Therefore, we cannot talk about resilience in the absence of risk factors, or adversity. In the educational context, risk factors can be represented by learning barriers. These conceptual delimitations on resilience are necessary in order to be able to introduce and conceptually describe the resilient educational climate.

The educational climate refers to "the relational, social, psychological, affective, intellectual, cultural, and moral environment that characterizes educational activity" (Bocoș et al., 2016b, p. 207). In general, educational climate is described or evaluated as positive or negative (Hamlin, 2021). By resilient educational climate, we refer to a learning environment in which students display resilient attitudes and behaviours and overcome obstacles that may occur in the learning process; the interactions and relationships that are established between educational actors support their resilience when faced with critical situations. Therefore, in order to build a resilient educational climate, the teacher will first identify the factors that disrupt learning in various curricular and extra-curricular contexts. Identifying these factors, which we have generically called, is the main interest of this research.

Research Questions

The research approach and design were thus designed to answer the following research questions:

What are the learning barriers most commonly identified by pre-university teachers among students?

Which types of learning barriers decrease mostly the resilience of the educational climate in pre-university education?

Purpose of the Study

Teachers consistently facilitate and supervise student learning. They are therefore the most suitable to give us an accurate, objective, extrinsic view of the potential obstacles that occur more or less frequently in learning activities. The main aim of this study is therefore to qualitatively analyse teachers' perceptions of the factors that are currently disrupting pupils' learning.

Another objective of this paper is to introduce at a theoretical level the concept of resilient educational climate and to describe it in order to develop a scale to measure the resilience of school climate.

An (educational) problem can be easily solved or rectified if its cause is well known and defined. However, when faced with a combination of causes and disruptive factors, a strategic approach and a prioritisation of interventions and educational management are required. With this study we aim to test whether there are significant differences between the categories of learning barriers in terms of their negative (destructive) impact on the resilient educational climate. In this way, we aim to identify on which level do children need more support to become resilient learners? Or which barriers to learning represent a significant risk for the resilient educational climate?

Research Methods

The research was structured in two main phases around the two research questions mentioned above. Regarding the research method, we opted for a questionnaire survey distributed online among pre-university teachers. A total of N=110 teachers participated in the study, of which 47% teach at primary school level, 30% teach at secondary school level, and the remaining 22% teach at high school level.

In the first part we conducted a qualitative analysis of teachers' open-ended responses on the barriers they identified in students' learning activities. The two open-ended questions were: "What are the factors that disrupt learning among your students?", "What do you consider to be the main cause of the low achievement of some students?", and their responses were analysed and coded using the online software’s voyant-tools.org and web.atlasti.com.

In the second phase we conducted a quantitative analysis of the data in order to test the null hypothesis, HA: There are statistically significant differences between categories of learning barriers according to the extent to which the educational climate supports resilience. In this regard, we used the parametric One-Way ANOVA test, and the statistical manipulation of the data was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.

A questionnaire was developed as a research tool for the gathering of the research data. The questionnaire consist of two sections that correspond to the two research questions. The first section includes the open-ended questions mentioned above and the items for collecting respondents' demographic data, and the second section includes closed-ended questions through which we aimed to measure the two variables: learning barriers (independent categorical variable) and resilient educational climate (dependent numerical variable) - indicating the extent to which educational climate supports resilience.

Findings

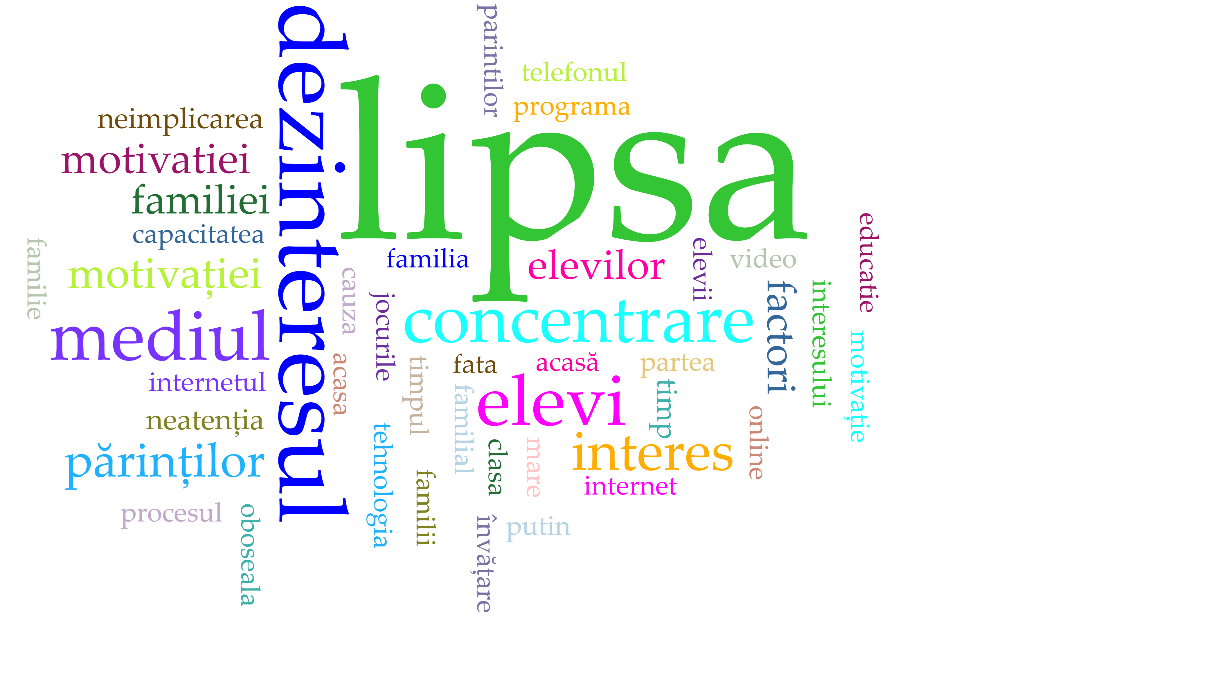

Initially, we wished to acquire an overview of the learning barriers most frequently mentioned and described by the teachers participating in the study. Therefore, we analysed the responses from the two open-ended questions on this topic in terms of lexical recurrence. We made a map of the words that were most frequently mentioned by respondents (Figure 1). For a more accurate visualisation, we have removed from the analysis linking words such as: of, and, may, or, are, so, to, a etc. It can be noticed that the word "lack" was mentioned most frequently (71 times), within phrases such as: "lack of concentration", "lack of motivation", "lack of interest". Also with a high frequency (19 times) we found the word "disinterest" being a synonymous form for the previously identified "lack of interest". So, from the primary analysis of the text, we can see that most teachers report the disinterest or the lack of interest of pupils and parents towards the educational process, to be a main cause for the low results and a disruptive factor for school learning. Also with a high frequency we find some words related topically to the idea of family: "families", "family", "parents", "home". Hereafter, we propose an in-depth analysis of the responses in order to understand precisely how the family could generate learning barriers.

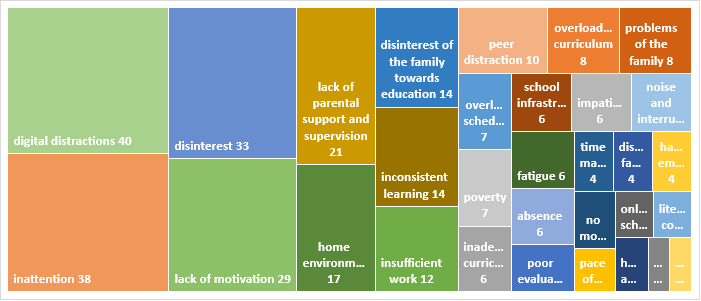

We identified recurring ideas in the recorded responses and grouped them around appropriate codes that describe the identified learning barrier (Table 1). Afterwards, we categorised these learning barriers according to the criteria mentioned in the theoretical foundation, thus obtaining the six main categories of learning barriers. Out of these, barriers related to curricular adaptation, cognitive barriers, emotional barriers and familial barriers were identified in a similar proportion.

We have noticed that digital or virtual environment was most often mentioned by teachers (absolute frequency = 40) as being a distractor for students' learning. Consequently, an additional significant category may be introduced into the previously proposed classification of learning barriers, namely: digital barriers (Figure 2).

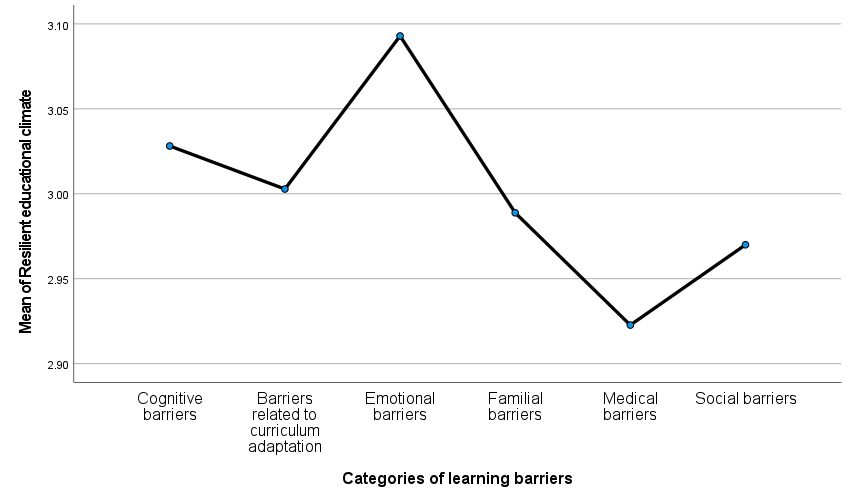

In the second phase of the study, we asked the same 110 teachers to choose the categories of learning barriers they consider to occur most frequently among their students out of the six mentioned above. Then, we asked them to assess the level of resilience of educational climate by answering the 10 items we proposed, which describe the resilient educational climate on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (where 1 - not at all and 5 - very much). If a teacher had chosen more than one category of learning barriers, then for each of them the value recorded by that subject for the dependent variable: resilient educational climate was associated. Among the items describing the resilient learning climate we exemplify: "2. I can say that my students are perseverant", "6. When my students have difficulties, they ask for help", "8. My students don't get discouraged and they keep working until they get the results they want". So the dependent variable, resilient educational climate scored numerical values in the range [1, 5], where 1- describes an irresilient educational climate and 5- indicates a very resilient educational climate.

In order to test the HA hypothesis, we first verified the normality of the distribution of the values for the dependent variable and the homogeneity of the variances. We obtained a normal distribution of the data for each category of learning barriers, since the values of the Skewness and Kurtosis indicators fall in the range [-1,1]. The homogeneity of variances criterion was also met, as we obtained p>0.05 in the Levene test.

A one-way ANOVA was performed to compare the effect of learning barriers on the resilient educational climate. After comparing the six means (Figure 3) we obtained an F(5,284) = 0.47, to which corresponds a significance threshold p = 0.79>0.05. There were no statistically significant differences in the means of resilient educational climate between the learning barriers categories. Consequently, the HA hypothesis was invalidated (Table 2).

Conclusions

This study contributes to a better understanding of the barriers to school learning and can be a starting point for teachers or educational managers to choose and develop strategies for facilitating learning. In order to capture this research topic more accurately, we analysed the data both qualitatively and quantitatively.

From the primary analysis of the data, it became clear that pupils' and their families' lack of interest for school is the main threat to school learning in the view of pre-university teachers, with these factors being mentioned most frequently. This highlights the discrepancy between the educational offer and the needs of the primary beneficiaries of educational services. These results may also indicate the need for a better adaptation of the educational approach towards the interests and needs of learners as primary beneficiaries of education, of learners' families (as secondary beneficiaries) and of the community and society (as tertiary beneficiaries).

From the qualitative analysis of the teachers' responses, we observed that most of them consider the digital or virtual environment, as well as social media, to be the main factors that distract students from learning. This may raise questions about teachers' openness to the digitisation of the educational process, since they perceive digital devices as a barrier to learning.

We sought to identify which of the categories of learning barriers most jeopardise a resilient educational climate, but from statistical analysis of the research data we could not identify significant differences between the six categories of learning barriers. As a future direction of study, further analysis in this regard can be conducted using a more complex and varied research instruments that ensures greater data accuracy. Also as a future research direction, we believe that an analysis of learning barriers from the subjective perspective of students would contribute to a clearer and more complex picture of this concept and could offer suggestions for improving the educational process in general.

References

Bocoș, M. D., Răduț-Taciu, R., & Stan, C. (2019). Dicționar praxiologic de pedagogie [Praxeological dictionary of pedagogy] (Vol. V). Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană.

Bocoș, M.-D., Răduț-Taciu, R., & Stan, C. (2016a). Dicționar praxiologic de pedagogie [Praxeological dictionary of pedagogy] (Vol. III). Paralela 45.

Bocoș, M.-D., Răduț-Taciu, R., & Stan, C. (2016b). Dicționar Praxiologic de Pedagogie [Praxeological dictionary of pedagogy] (Vol. I). Paralela 45.

Dierking, L. (1991). Learning Theory and Learning Styles: An Overview. Journal of Museum Education, 16(1), 4−6.

Forde, C., & OBrien, A. (2022). A Literature Review of Barriers and Opportunities Presented by Digitally Enhanced Practical Skill Teaching and Learning in Health Science Education. Medical Education Online, 27(1).

Greitens, E. (2020). Reziliența: Înțelepciune câștigată cu greu pentru a trăi o viață mai bună [Resilience: Hard-Won Wisdom for Living a Better Life]. ACT SI POLITON.

Hamlin, D. (2021). Can a positive school climate promote student attendance? Evidence from New York City. American Educational Research Journal, 58(2), 315−342.

Ionescu, S. (2013). Tratat de reziliență asistată. [Assisted resilience treatise]. București: Trei.

Levine, S. (2022). Psychological and social aspects of resilience: a synthesis of risks and resources. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 5(3), 273−280.

Metcalf, K., Jenkins, D. B., & Cruickshank, D. (2016). The Act of Teaching. Iowa: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company. https://he.kendallhunt.com/sites/default/files/heupload/Metcalf_Chapter4.pdf

Nurjanah, M. (2022). Barriers to Online Learning during the Covid-19 Pandemic in the Dimension of Class Teacher Readiness at Elementary School. IJIS Edu: Indonesian Journal of Integrated Science Education, 4(1), 61−66. https://garuda.kemdikbud.go.id/documents/detail/2509761

OECD. (2019). Future of Education and Skills 2030: Conceptual learning framework - Learning compass 2030. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/

OECD. (2021). Education Policy Outlook 2021: Shaping Responsive and Resilient Education in a Changing World. OECD Publishing.

Verdeș, L., & Baciu, C. (2022). Resilient primary school teachers in pandemic times and their self-assessment on the quality of online teaching activity. A retrospective analysis. In Educatia 21 Journal, 22, 82−86.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

10 April 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-961-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

5

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1463

Subjects

Education sciences, teacher education, curriculum development, educational policies and management

Cite this article as:

Verdeș, L., Baciu, C., & Oana Câmpean, A. (2023). Identifying Learning Barriers and Their Impact on the Resilient Educational Climate. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues - EDU WORLD 2022, vol 5. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 84-93). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23045.9