Abstract

The present paper presents current research on CLIL methodology, curricular practices and experiments in the areas of citizenship education in lower and upper primary schools (ages 5 to 12) across Europe. It aims to give a brief overview on the implementation and results of the international cooperation Erasmus+ project, CLIL for Young European Citizens, as well as to inform teachers and teacher educators on how best to plan CLIL lessons in citizenship, environmental, and financial education. The paper also considers topics, themes and methodological approaches that may be developed for CLIL in primary suggested in classroom pedagogical materials, Open Educational Resources (OERs), and resources created by primary and CLIL teachers that can serve as inspiration. Families’ involvement and cooperation with teachers is central to learners’ development and welfare. From the answers to the questionnaire, we can see that most teachers involve families in classroom activities, although the degree of involvement varies.

Keywords: CLIL, digital skills, OERs, primary school education, PBL

Introduction

The objective of the present paper is to describe the outcomes and practice developed within an Erasmus + funded European project implemented in Italy, Portugal, Spain and Romania, for a period of three years.

The main object of the Erasmus + CLIL4YEC project is to promote the use of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) at primary school level, focusing on the development of up-to-date competences on the following topics: European citizenship, environmental sustainability and basic financial education. The CLIL project combines the development of key competences and basic skills of pupils with to cross-curricular and intercultural education for European Citizenship using integration of language learning in the teaching of curricular subjects. Thus, the intercultural dimension promoted by the CLIL4YEC project can open up new opportunities for primary school pupils, e.g. engaging in virtual exchanges and on line peer-to-peer collaboration across different countries and cultural spaces, facilitated by teachers and families (CLIL for Young European Citizens, n.d.).

The project is also related to the development of digital skills. Primary school teachers have the possibility to explore, impart, and use again Open Educational Resources by discovering the online OER repository concerning the three major topics mentioned above; it also supports teachers to embrace original practices - designing innovative lesson plans - that will involve, in the learning process, primary school students as well as their parents.

Problem Statement

Many studies underline that CLIL develops greater intercultural awareness (Coyle et al., 2010; Coyle et al., 2009), and is “a tool to explore and construct meaning” in a “a meaningful context”. With CLIL “learners can engage in deeper learning about themselves and others, and, at the same time, experience the process from the perspective of their counterparts” (Coffey, 2005; Harrop, 2012, pp. 49-62). The project adopts the CLIL methodology to sustain and improve cross-curricular and intercultural education on interrelated major subjects about wellness and developing within the European Union: train primary school students to grow into good European citizens, enable them acknowledge the current environmental issues, and cultivate basic financial skills (which are essential to help students become aware of what is required to produce work).

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is an educational approach that is widely spread in the national or regional curricula of some countries (e.g. Spain) and less so in others (e.g. Portugal and Romania), although all the countries involved have been developing bilingual education to a greater or lesser extent in primary schools. We will refer to lower primary schools to cover the 5-to- 10-year-olds, and to upper primary school to refer to the 10-to-12-year-olds.

The term CLIL was invented in 1994 by David Marsh and it refers to situations where students are taught through a foreign language with dual-focused aims, namely the learning of content and the simultaneous learning of a foreign language (Marsh, 1994).

CLIL started to be implemented in the mid-1990s through pilot projects in several European countries. One of the earliest and most successful was the Bilingual Education project (BEP) of the Ministries of Education and the British Council. This program is still developed in some schools and was used as a model for further developments in the Primary and Secondary educational system.

Alejo-González and Piquer (2010) while summarizing some of the main features of CLIL programs in Extremadura, Spain, allow for a systemic approach to CLIL: in some countries bilingual programs were ‘elective’ before it progressed to ‘CLIL schools’, while in other countries, they still are.

There are some important principles for implementing CLIL successfully. It is important to promote partnered schools (primary-secondary) to ensure the students’ CLIL instruction throughout their educational life. CLIL projects, while dominantly in English throughout Europe, can elect other languages, such as French, German or Portuguese. The number of CLIL subjects generally ranges between a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 3 content subjects that each school can include in their project. The L2 should be used for at least one session a week. All CLIL students have to take an additional Foreign Language and to attend these classes for additional time. Not all CLIL teachers are required to have a language certificate or methodological training on bilingual education. CLIL programs are generally coordinated by a language specialist.

Also, research and studies have shown the importance of parents’ involvement and community’s involvement in CLIL at schools. According to Mehisto et al. (2008), community is one of the principles which drive the CLIL model. The authors point out that when students feel members of a learning community and have the self-confidence and skills to work within a group, they enrich their learning experience. The local community, parents, students, and teachers should be partners in education. Students can also be encouraged to become aware of their role within the classroom, the local and global context through physical and virtual interactions with other students in other contexts.

If our goal is to ‘prepare European students to compete in the global economic, political, and cultural world in which multilingual interactions are becoming increasingly frequent’ (Tobin & Abello-Contesse, 2013, p. 206), Content and Language Integrated Learning has been foreshown as the potential prerequisite to tackle the language needs in Europe. This ‘innovative approach to education’ (Pérez-Vidal, 2013, p. 64) has been considered a ‘well-recognized and useful construct for promoting L2/foreign language (FL) teaching’ (Cenoz et al., 2013, p. 16). As these same authors have stated (Cenoz et al., 2013, p. 4), CLIL is considered an ‘“umbrella” term that includes many variants and/or a wide range of different approaches.’ Actually, a wide range of models can be identified within CLIL, as it comes ‘in all shapes and sizes’ (Smit, 2007, p. 3), given that it is not a homogeneous educational concept and there is not a unique outline that can be functional across Europe (Coyle et al., 2010). CLIL is ‘commonly perceived as a flexible operational framework for language instruction, with a heterogeneity of prototypical models and application options available for different contexts and pedagogical needs’ (Dueñas, 2004, p. 75). This extensive variety of models which CLIL covers is thought to be reliant on a series of operating factors (Coyle et al., 2010), environmental parameters (Wolff, 2005), or variables (Rimmer, 2009, p. 4), such as the choice of subjects, the degree of language and content teaching, the time of exposure, or the levels of student and teacher language fluency. Nevertheless, regardless of this heterogeneous outlook, CLIL is currently acknowledged to be a unique form of education in Europe (Cenoz et al., 2013) and certain common characteristics can be identified when applying it in teaching (cf. Pérez Cañado, 2012).

Research Questions

In this article, the following questions were explored, in the Romanian primary school context:

What are the best ways of using CLIL with specific content and activities on three topics of great interest: European Citizenship, Environmental Issues especially related to pollution and waste, and Basic Financial Education, which can also include some elements useful for subsequent development of entrepreneurship? These three topics together with plurilingualism are essential for the growth of European children and European identity itself, especially given the crises of the present situation.

What are the best specific strategies and resources for the involvement of the pupils’ families in the CLIL process?

What are the best OERs (Open Educational Resources) that can be used to develop the three above topics through CLIL, at primary school level?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the present paper is to present the outcomes of the Erasmus+ project implemented in primary schools across Europe.

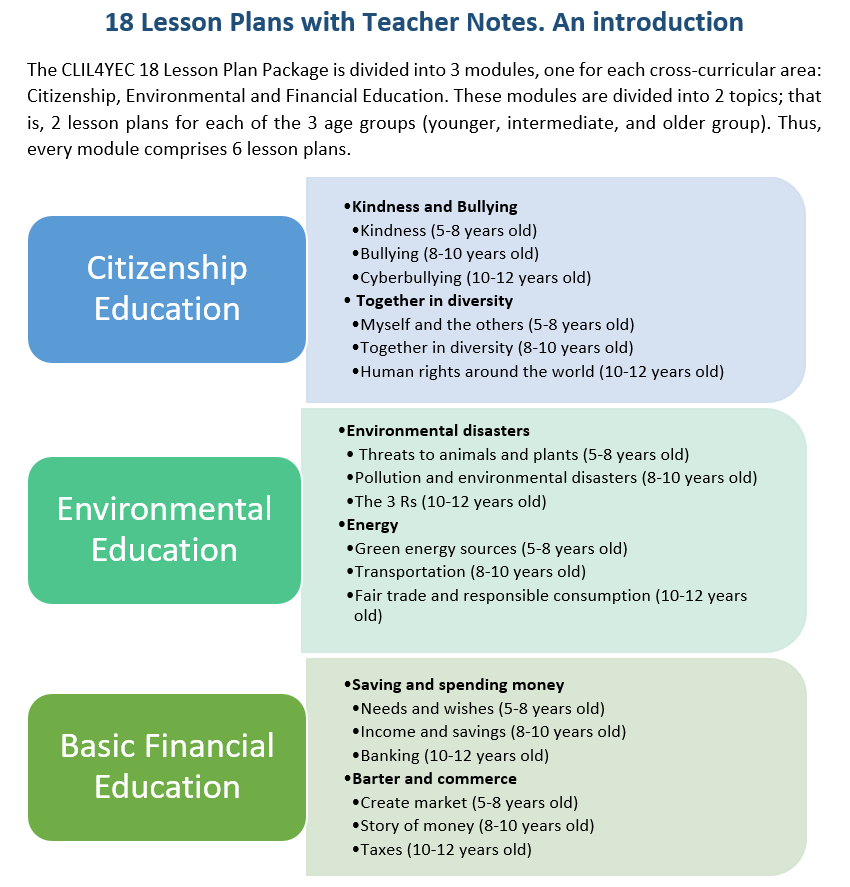

Within the CLIL for Young European Citizens project, researchers and primary school teachers produced seven intellectual outputs to address the current European priorities, such as encouraging a complete approach to language teaching and learning; supporting students in acquiring and developing key competences and basic skills and providing open education and new practices in a digital era. The products of the collaborative work of the consortium were: an preliminary study on how to the CLIL methodology to develop European citizenship; environmental sustainability; and financial education in primary school students; a census of OERs ( open educational Resources) to be used in CLIL lessons to design cross-curricular activities on the topics mentioned above; a OER’s repository focusing on activities CLIL, with sharing and rating functions for teachers; a guide addressed to teachers on how to use CLIL in primary schools for innovative activities on the three cross-curricular topics, a second guide for teachers on how to implicate pupils’ families in CLIL activities; a free access e-Course for teachers and pupils’ families on how to use CLIL to develop pupils’ competences in European citizenship, environmental sustainability, and basic financial education. The last intellectual output gathered primary school teachers from 4 countries to develop, together with researchers a pack of CLIL didactic materials for teaching on intercultural and cross-curricular subjects: 18 lesson plans on the three topics to be freely downloaded from the project’s website (CLIL for Young European Citizens, n.d.).

The project targeted primary schools (teachers; pupils; parents, trainers); language schools, universities, and specific organizations that focus on training primary school teachers. The project’s outputs have been developed by the partnership between the coordinator, and 9 organizations illustrative of both tertiary and primary education in the partner countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Romania).

Research Methods

The research methods used in the framework of the cooperation project, carried out over a period of 36 months were the observation, the analysis of the products of the activities carried out by the primary school children and a survey based on the questionnaire applied to the participating primary school teachers regarding the selection of PBL-based lesson plans on European Citizenship, Environmental education and Basic Financial Education, out of the 18 PBL-based lesson plans developed within the project, during a 1-week teacher’s mobility, which involved 50 primary school teachers from the partner countries> Italy, Portugal, Spain and Romania. In Romania, the piloting phase took place at the Alexandru Davila Secondary School, Pitesti, Arges. 10 primary school teachers were involved in the piloting activities, as well as 350 primary school pupils and their families.

Findings

Romania implements CLIL (for English or French) only at middle or high school level, which requires students who choose to study in these institutions to pass a test of the level of language proficiency in that language (minimum A2 in high school and B1 in high school).

From 2015 till present, in Romania, CLIL teaching was used, in the primary cycle, due to some Erasmus + Projects. In the Romanian public education system, this methodology is not yet addressed as part of the National Curriculum.

Student’s knowledge in citizenship are related to the Romanian Civic education curriculum. Civic education is taught in the 3-4th grade (1 hour/week) by the primary education teacher. Presently, the compulsory system of education in Romania includes two such subjects: “Civic education”, which is studied in the last two years of the primary school by children from the age of 9 to 11, and “Civic Culture”, which is studied in the last two years of junior secondary school by children from the age of 12 to 14. The curriculum of the subject “Civic education” for the 3rd grade students includes a chapter called “The Person”, which comprises several lessons. The students study the notion of “Me” and “The Other”, and moral features of identity, such as: kindness, respect, courage and self-trust. The curriculum for 4th grade students introduces the notion of belonging in relation to the local, national and European community. The national curricula include examples of activities which can be used by teachers in these lessons: collages of images which reflect the national or European territory, written descriptions of these places, recognition exercises of the EU and national symbols.

Environmental education in school represents a constant concern in all categories of activities. This approach is of major importance since the first forms of organization of children's knowledge of the environment appear in pre-primary education and continues in primary school through reintroduction of the subject Knowledge of the Environment starting with Ist grade. Since environmental issues have a multidisciplinary character and a high complexity, a rapid and difficult to predict evolution and a priority, the contents must be related to the future of the planet and the survival of the human species. Given these aspects, the more appropriate way of introducing ecological education in schools is the infusion of some of its dimensions within the existing disciplines. Through interdisciplinary treatment, it can lead to the formation of a vision and a coherent system of attitudes and behaviours according to the school age.

The topic of Financial education does not exist in the National Curriculum with a compulsory character, but it is carried out as an optional course in the 3rd and 4th grades. There is no connection to CLIL in the Romanian curriculum. This topic does not appear in the National Curriculum for primary education, with a compulsory character, but it is carried out as an optional course in the 3rd and 4th grades. 7 years ago, an optional course of financial education was introduced, at a national level, through a national project, through which primary schools received free teaching materials, guides for teachers, auxiliaries for students on financial education. For about 3 years this project has grown and initiated a competition for students, at a national level, in which students from 3th and 4th grades. The competition was known as the "Olympics of small bankers". The Romanian Commercial Bank also initiated and carried out a project called - "The School of money on wheels". Through another project, called Junior Achievement-JA Romania, schools have benefited from free materials (games, drawings, auxiliaries, guides) to teach Financial education in primary schools, but there is no connection to CLIL.

During the Implementation of the C4CYEC project, 10 primary school teachers form were involved in various activities, prior to the piloting phase in their school, such as: online mobility of teachers were, in collaboration with other teachers from the partner countries, they took part in workshops mainly devoted to the CLIL methodology as well as PBL – Project Based Learning, they also worked together in order to produce 18 CLIL PBL-based lesson plans (which will be made available on the website of the project, https://clil4yec.eu/). Moreover, they were involved in the selection of Open Educational Resources in order to produce an online repository, available online. The aim of Intellectual Output 2 (IO2) is to report on existing Open Educational Resources from all partner countries for Primary School English CLIL lessons and activities on the following topics: Citizenship Education, Environmental Education, and Financial Education. The Guide to OERS follows a standard for evaluation, analysis and description, adopted by all partners to assure the consistency of the body of work produced in the four different countries. After the research and selection of OERs and a review of the OERs selected by UDP for the C4C project Guide to OERs, which was completed by 15th May 2020, 2 Romanian teachers with expertise in CLIL from the local partner school were asked to select the best OERs for each topic and to review a selection of the best OERs in each category and describe how they would customise them.

During the Piloting phase, teachers from Alexandru Davila Secondary School, Pitesti tested 8 PBL-based lesson plans produced in Volume 2 of the guide addressed to teachers on how to use CLIL in primary schools for innovative activities on the three cross-curricular topics, which aims to serve as a comprehensive introduction to the use of CLIL in Primary School to develop the broad cross-curricular areas (mentioned above), and targets CLIL teachers who would like to develop topics in these areas in their lessons (also available online on the project website, https://clil4yec.eu/. Volume 2 of the Guide includes the 18 PBL Lesson Plan Package with teacher notes developed for the CLIL4YEC project by CLIL teachers, researchers, and teacher educators (Figure 1).

Thus, the Romanian primary school teachers implemented CLIL project based lessons under all three major topics addressed by the project, such as: Banking, Environmental disasters, Green energy, Story of money, Human rights around the world, Kindness, Myself and the others, Human rights around the world, Environmental disasters and Threats to animals and plants. The activities were carried out from May to June 2022, and involved over 350 primary school pupils as well as their families.

Each lesson was developed on a period of 2 hours, divided into sequenced steps to be developed in different curricular subjects along three weeks. Students at this level could work in an autonomous way and feel confident when studying in English. They could understand simple texts and produce simple sentences in English. Families’ involvement was also required.

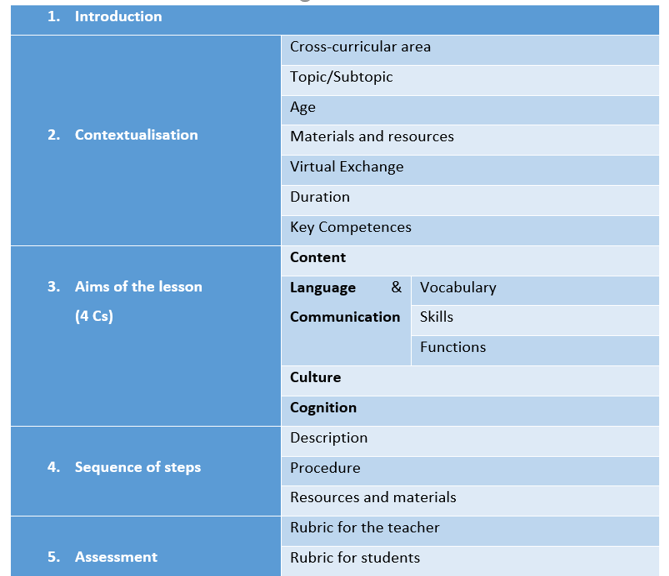

A general format of lesson plan was used throughout the implementation phase of the project, containing: the cross-curricular subject addressed, a sub-topic, suitable age of students, resources and materials needed, use in virtual exchange with other classes around Europe, an introduction stating the aim and competences to be developed, contents, language and communication items, a description of the sequence of steps. There are usually 5, 6 steps in each lesson plan, as follows: a warm-up activity (which takes around 30 minutes in week 1) which also includes a thought-provoking/ a driving question; Step 2 (30 minutes in week 2) where students are involved in a hands-on activity in class; The following steps involve peers and families in making of a project related to the topic.

Each lesson plan provides an assessment grid, a letter to the students’ families with a description of the task to be performed at home, with their help and support, as well as appendices with all the materials needed. Moreover, each lesson plan contains links to suitable Open Educational Resources available online.

Students’ families also took part in an online course developed under IO5 of the C4C project, the a second guide for teachers on how to implicate pupils’ families in CLIL activities. The handbook for Parents, -(available at https://view.genial.ly/60266ee0d4fb4a0d2069108c). This booklet is a user-friendly guide to support parents, grandparents, and students’ families involved in the CLIL for YEC program.

Following the implementation of the activities, all teachers involved provided feedback in the form of a questionnaire regarding the efficiency of the lesson plans, providing detailed information on the piloting process. To do so, several grids were provided for each of the lesson plans. The teachers who participated in the piloting are indicated, as well as their comments on the lesson (stronger and weaker points). Moreover, it is specified whether they have changed any aspects of the lesson plan, or if they have added new materials.

All Romanian teachers gave positive feedback, as described in the following testimony examples:

“My piloting followed a CLIL approach since I used English for teaching both content and language. It was also a successful process in which we could bring together English and Financial Education

My lessons followed the PBL approach by means of including the mini-project, social interaction, great emphasis on learning – by- doing and sequencing the activities into appropriate steps.

The activities were exciting and enjoyable for the students and I could finish the whole lesson plan during my piloting.

Families were interested and eager to let their children participate in this international project, so I succeeded in involving them.

Most families were happy to help their children during the mini-project, to monitor them and considered the activities carried out useful and efficient.

There wasn’t a Virtual Exchange included in my lesson plan.

I used OERs. The OERs had a great impact on my students.

Students were really interested in talking about banking, so the driving questions truly engaged them in the topic.

I totally agree with the fact the final product gave answer to the driving question.

Most of the students were able to complete the project and they liked it.

My students were really engaged in the lessons on account of being stimulated by the use of technology and their active participation increased the level of language comprehension.

Although some students had problems to understand some information, they were encouraged to continue the respective activity, but adapt it to his/ her own level and style.

The “Can-do” assessment rubrics were really useful for assessing students, but I could also notice a change in their future actions, meaning that they started to use some words and expressions about financial education.

In my opinion this lesson plan includes all the key aspects needed for obtaining a beneficial and long-term learning experience. It includes interactive activities that are meant to boost the students’ motivation and creativity.

During the lessons, I could notice their interest towards the activities, they were eager to communicate and collaborate, offering their help more than usual. I think that one of the most important outcomes concerned the students’ ability to retain the targeted information without any extra effort, just by means of the tasks involved. Undoubtedly, using real-life situations and learning-by-doing activities lead to a long-term learning.” (Florentina Tudorache, primary school teacher, Alexandru Davila Secondary School, Pitesti).

Students have been interviewed after completing the implementation and their feedback was extremely positive. In fact, students asked for an optional course following the CLIL and PBL approach, for the following school year: “(Idem).

Conclusions

Overall, the goals of the Erasmus+ project were fully achieved in the Romanian setting:

encourage the use of CLIL methodology at primary school level

cultivate three major cross-curricular topics in primary school children;

offer new opportunities at primary school level, such as on-line peer-to-peer co-operation between different countries and in various cultural spaces, as well as engaging students in virtual exchanges, guided by teachers and parents.

support primary school teachers to use Open Educational Resources by accessing a CLIL dedicated online OER repository;

enable teachers to embrace original practices, designing inventive lesson plans that will implicate pupils and parents in the learning process;

promote and increase cross-curricular instruction on three topics linked to each other and linked to wellness and evolving within the EU: train pupils to become European Citizens, help them to acknowledge the current environmental issues, cultivate basic financial skills;

support teachers to benefit from face to face and online training activities (eLearning), thanks to the e-Course available for teachers and parents;

download the guides that will be made available in digital format;

Finally, support teachers to adopt innovative practices, thanks to the creation of original lessons, which will involve pupils and their families in the learning process.

Acknowledgments

The present paper shows the findings, work and products from the implementation of the project, with no.: 2019-1-IT02-KA201-063222, implemented under the Erasmus+ Program - Call 2019 - Key Action 2 Strategic Partnership – KA201. ll the materials referred to in the present article have been developed within the project and can be freely downloaded at https://clil4yec.eu/. (Project’s Consortium at https://clil4yec.eu/partners/).

References

Alejo-González, R., & Piquer-Píriz, A. M. (2010). CLIL teacher training in Extremadura: A needs analysis perspective. In Y. Ruiz de Zarobe, & D. Lasagabaster (Eds.), CLIL in Spain: Implementation, results and teacher training (pp. 219-242). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Cenoz, J., Genesee, F., & Gorter, D. (2013). Critical Analysis of CLIL: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. Applied Linguistics 2013, 35(3), 1–21.

CLIL for Young European Citizens. (n.d.). Content and Language Integrated Learning. https://clil4yec.eu

Coffey, S. (2005). Content-based learning. In Cerezal, F. (Ed.), De la Práctica a la Teoría: Reflexiones sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de inglés [From Practice to Theory: Reflections on Teaching and Learning English] (pp. 49-62). Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá.

Coyle, D., Holmes, B., & King, L. (2009). Towards an integrated curriculum: CLIL national statement and guidelines. The Languages Company.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). LIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge University Press.

Dueñas, M. (2004). The Whats, Whys, Hows and Whos of Content-based Instruction in Second/ foreign Language Education. International Journal of English Studies, 4(1), 73–96. https://revistas.um.es/ijes/article/view/48061

Harrop, E. (2012). Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Limitations and possibilities. Encuentro, 21, 2012. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED539731.pdf

Marsh, D. (1994). Bilingual education & content and language integrated learning. In International Association for Cross-cultural Communication (Eds.), Language Teaching in the Member States of the European Union (Lingua). University of Sorbonne

Mehisto, P., Marsh, D., & Frigols, M. J. (2008). Uncovering CLIL. MacMillan Books.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2012). CLIL Research in Europe: Past, Present, and Future. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(3), 315–341.

Pérez-Vidal, C. (2013). Perspectives and Lessons from the Challenge of CLIL Experiences. In C. Abello-Contesse, P. M. Chandler, M. D. López-Jiménez, & R. Chacón-Beltrán (Eds.), Bilingual and Multilingual Education in the 21st Century. Building on Experience (pp. 59-82). Multilingual Matters.

Rimmer, W. (2009). A Closer Look at CLIL. English Teaching Professional, 64, 46. www.etprofessional.com

Tobin, N. A., & Abello-Contesse, C. (2013). The Use of Native Assistants as Language and Cultural Resources in Andalusia’s Bilingual Schools. In C. Abello-Contesse, P. M. Chandler, M. D. López-Jiménez, & R. Chacón-Beltrán (Eds.), Bilingual and Multilingual Education in the 21st Century. Building on Experience (pp.231–255). Multilingual Matters.

Wolff, D. (2005). Approaching CLIL. In D. Marsh (Coord.), The CLIL Quality Matrix. Central Workshop Report. http://www.ecml.at/mtp2/CLILmatrix/pdf/wsrepD3E2005_6.pdf

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

10 April 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-961-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

5

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1463

Subjects

Education sciences, teacher education, curriculum development, educational policies and management

Cite this article as:

Lazăr, A., Langa, C., Sofia Loredana, T., Maria Magdalena, S., & Sarbu Luiza, V. (2023). Using CLIL in Cross-curricular Education to Develop European Citizenship. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues - EDU WORLD 2022, vol 5. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 25-35). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23045.4