Abstract

Intercultural openness represents a person’s positive curiosity and desire to know details about cultures other than his/her own. This attitude is consistent with other attitudes and behaviours which make up a progressive worldview, as opposed to a conservative worldview. At this moment, there is no pertinent research concerning Romanian teachers’ intercultural openness and, consequently, worldviews. This study will compare the level of intercultural openness of teachers in Western Romania with the levels of intercultural openness within the general Romanian population investigated by the World Values Study, wave 7, in order to give an answer to the question “Are teachers more progressive or more conservative than the general population?” For this, we extracted 9 questions from the WVS questionnaire and we asked 222 Transylvanian teachers to answer those questions, comparing afterwards their answers with those found in the WVS database, while paying attention to the differences between subjects living in rural areas and those in urban areas. The results prove beyond doubt that teachers in Western Romania show an overwhelmingly increased level of intercultural openness when compared to the general population and, thus, they could serve as a positive factor for change if centralized policies would direct their efforts for that.

Keywords: Intercultural openness, teachers, tolerance

Introduction

One particular sub-genre of intercultural studies is being represented by those studies which try to show how a majority population opens itself to the values of different cultures. Although some researchers have mentioned the notion of “(inter)cultural openness” (Coulangeon, 2017; Deardorff, 2006; Fowers & Davidov, 2006), the concept has not yet gathered sufficient traction to be widely known and clearly defined. For the moment, I shall define “intercultural openness” as a person’s global cognitive and emotional behavior characterized by curiosity and interest in other culture’s than his / her own, and the lack of negative biases towards the respective different cultures. If we take as an axiom the fact that the world can be described (in a Hegelian inspired manner) as a dichotomy of “conservative vs. progressive” (see Middendorp, 2019) then intercultural openness is a clear indicator of being in the progressive cluster, and not the conservative one. Being conservative or progressive consists of more than just responses to some given questions; they are, actually, worldviews. As Dilthey (2020) explains this notion which he made popular (naming it Weltanschauung in German), the worldview represents a perspective on life that brings together cognitive, volitive, affective and creative aspects of human experience. We presume that intercultural openness is one of those aspects which can help us understand if a person is rather conservative (when the intercultural openness is low) or progressive (when this feature is high).

The collective stereotypes concerning Romanian teachers. Are they conservative or progressive?

One common prejudice regarding teachers is that they are somewhat special when compared to the rest of the population, in a completely positive way. Many people think that teachers are just better people than average people: more intelligent, more educated, they express themselves better in foreign languages, use digital technology with more ease, they are more tolerant and empathic and so on. Usually, such idiosyncrasies are used in the context of some ” illo tempore”, (”the old days”) when teachers used to be in such a way, obviously contrasted with ”our days”, when teachers are no longer like that. Needless to say, this nostalgic and idealistic portrait of teachers is usually created by people fond of conservative values, but nonetheless it is quite widespread in the general population, regardless of political views. School itself gladly uses as teaching materials pieces of literature which bring forward anachronic models of teachers such as “Mr. Rose” (a fictional ideal teacher created by influential communist writer Mihail Sadoveanu), Aron Pumnul (a teacher idolized by Romanian national poet, Mihai Eminescu) or “Bădița Vasile”, a 19th century fictional character created by Ion Creangă, based on real examples of religious teachers. The ideal Romanian teacher as he/she was created by the collective imagination presumed, like for many other nations, erudition, wisdom, impeccable moral behaviour and, sometimes, harshness (Catana, 2015). In more recent times, communist propaganda movies also portrayed teachers in an idealized manner, suggesting that they were moral pillars of society, presumed to be morally and ideologically flawless. One very suggestive example can be found in the popular high school movies created by director Nicolae Corjos in the 1980s, based on George Șovu’s screenplays: “Declaratie de dragoste” (“Declaration of Love”, 1985), “Liceenii” (“The High Schoolers”, 1986) or “Extemporal la dirigentie” (“Tutor Class Test, 1988). Philosophy teacher Socrates is profoundly empathic and practices a communist version of positive pedagogy and one of the underlying motifs of the movie is that young people should strive to be like Socrates, a model for openness and reason (Indolean, 2020).

On the other hand, especially in the recent years, more and more voices of progressive and anti-establishment intellectuals pointed out that much of the mythology surrounding our schools and teachers is completely unrelated with reality, retro projecting nostalgic idiosyncrasies over the past generations of education (Sdrobiș, 2015). According to such voices, the illusory “Golden Age” of Romanian education (the interwar years, for example) was not golden, after all and - if we tend to replicate that kind of schooling - we will find that it is not suited for the contemporary times (Maci, 2018).

How can we compare teachers to the general population regarding intercultural openness?

Over time, several attempts have been made to create tools which would allow us to describe cultures in a quantitative manner. The most popular and successful two attempts are arguably Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory and the World Values Survey. Hofstede’s theory asserts that there are several dimensions which can fully describe a national culture and each of these dimensions can be accurately measured through self-assessment. The final version of Hofstede’s theory describes six cultural dimensions which translate in six different outputs: the power distance index, individualism vs. collectivism, masculinity vs. femininity, the uncertainty avoidance index, long term orientation vs. short term normative orientation, and indulgence vs. restraint (Hofstede, 1991). Since the 1990’s, Hofstede’s scale became increasingly popular and rose to prominence, being considered the norm in the field by many of the scientists interested in creating cultural profiles or cultural comparisons between nations.

The alternative tool is the equally popular World Values Survey (WVS), a research project which takes place regularly in almost 100 countries, since 1981, and which has now reached its 7th wave. The fact that the minimum sample consists of at least 1000 participants in each country, makes the results deeply relevant. The master questionnaire comprises more than 200 questions or variables, all of which are adapted (if needed) to the specific of each country; the questions address various topics and are meant to reveal all of the essential values and beliefs of people. The most important aspect of the survey is the fact that the entire massive database (unequalled by other studies) is available free of charge for researchers and members of the academia, a fact which allows practically an infinite number of statistical procedures which can reveal previously unsuspected relationships between various parameters, attitudes and beliefs.

Problem Statement

Although there is some research on various aspects of Romanian teachers’ cultural attitudes and beliefs (Chircu & Negreanu, 2010; Frumos, 2018; Mara, 2021; Niculescu & Bazgan, 2017), at the moment, there are no pertinent Romanian studies which would compare teachers’ intercultural openness to the general population's. We cannot state, from this point of view, if teachers are more progressive, more conservative or in the line of the general population. The conclusion of such a study should prove of major importance for decision factors (government, local authorities etc.) when designing policies meant to improve the performance of teachers in intercultural environments (Kiss, 2020).

In 2017, the national mass-media popularized the conclusions of a large study performed on Romanian teachers (Badescu et al., 2017) and drew attention - on a rather sensationalist manner - on the fact that many teachers supported values considered by some to be unfit for the 21st century (such as the death penalty, dictatorship, homophobia and so on). Very few reactions to this study tried to analytically interpret the findings and to compare the results concerning teachers to the data referring to the general population. In a very brief reaction posted on a website, sociologist Claudiu Tufis (2018) noted that “teachers actually come from the population, and they reflect the population’s values” and drew some short comparisons between the values of the study and values included in the WVS (wave 6 at that time). His concluding remark was that teachers seem to be, in fact, more tolerant and more democratic than the general population and that they are one of the very few factors which could help to fully democratize Romania.

Research Questions

We will try to answer these specific questions: how do Romanian teachers feel towards representatives of other cultures? Do urban teachers have different intercultural attitudes than rural teachers? How do teachers compare with the general population concerning their intercultural openness?

Purpose of the Study

The main goal of this study is to collect and analyse Romanian teachers’ opinions concerning representatives of other cultures and to compare their answers with the answers provided by the general Romanian population in the World Values Survey. We will try to find out, based on empiric data, if the conclusions of Tufis (2018) that teachers are more tolerant and open to diversity than the majority of the Romanian population are valid or not.

Research Methods

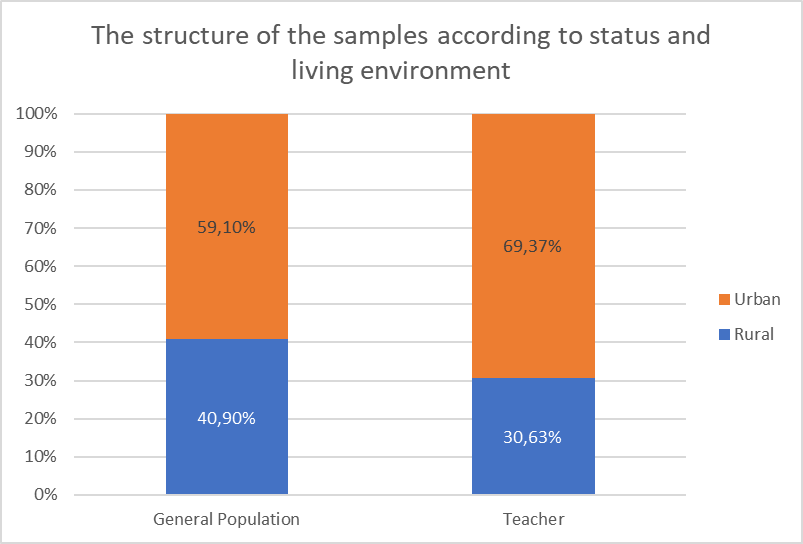

Participants. We chose to conduct our study only in Transylvania because of the very different intercultural specificity of Romania’s historical provinces. Further studies should contrast our findings with similar research conducted in Moldova and Wallachia. For our study, we had the support of 222 teachers living in Western Romania (52,1% women, respectively 47,9% men). For the general population group, we used the World Values Survey wave 7 database (Haerpfer et al., 2020) available as an open-access database on the WVS website (www.worldvaluessurvey.org) out of which we extracted the 357 subjects residing also in Western Romania (in the same counties as our sample of teachers) (Figure 1). In the teacher sample, 69% (n = 154) reside in urban environments, and the rest of 31% (n = 68) in rural environments, a proportion which does not match the general structure of the Romanian population, but this bears no significance in our study since the structure of the WVS sample is relatively unbalanced as well (approximately 60% urban vs. 40% rural respondents; respectively 211 vs. 146).

Objections can be raised regarding the fact that teachers could already have been included in a well-calculated amount in the general population sample which would render our comparison useless; unfortunately, there is no data concerning the occupational fields of people included in the WVS and we can only speculate on the fact that teachers were included in a representative and adequate number in the research. The current population of Romania is estimated between 19 million people (according to The World Bank) and 22 million people (according to The Romanian National Institute for Statistics), while the number of teachers in the country is approximately 201.000 (according to the Ministry of Education, 2021). Of these, approximately 6.5 million people live in Western Romania, and 64,972 teachers live and work there. A brief operation, based on normal distribution and the rules of sampling, will give us the conclusion that the WVS conducted in the Western counties of Romania might have included 3 to 5 teachers, which is - obviously - completely irrelevant. Therefore, our study cannot be accused of being redundant, but - quite the opposite - it provides insights on matters uncharted before at this level (i.e., the way in which teachers can be compared to the general population when it comes to intercultural openness).

Research instruments. From the master questionnaire of WVS wave 7, we selected only 9 questions, considered by us as relevant for the topic of intercultural openness. These questions had the following numbers in the WVS questionnaire: 12 (which addresses the matter of the importance of tolerance and respect while educating children), 19,21,23, and 26 (which create a “possible neighbour” scenario and investigate the subjects’ feelings on having as neighbours people of a different race, immigrants, people of a different religion or people who speak a different language), questions 62 and 63 which address the matter of trust towards people of another religion or another nationality, and questions number 121, and 123, concerned with different aspects of immigration.

Findings

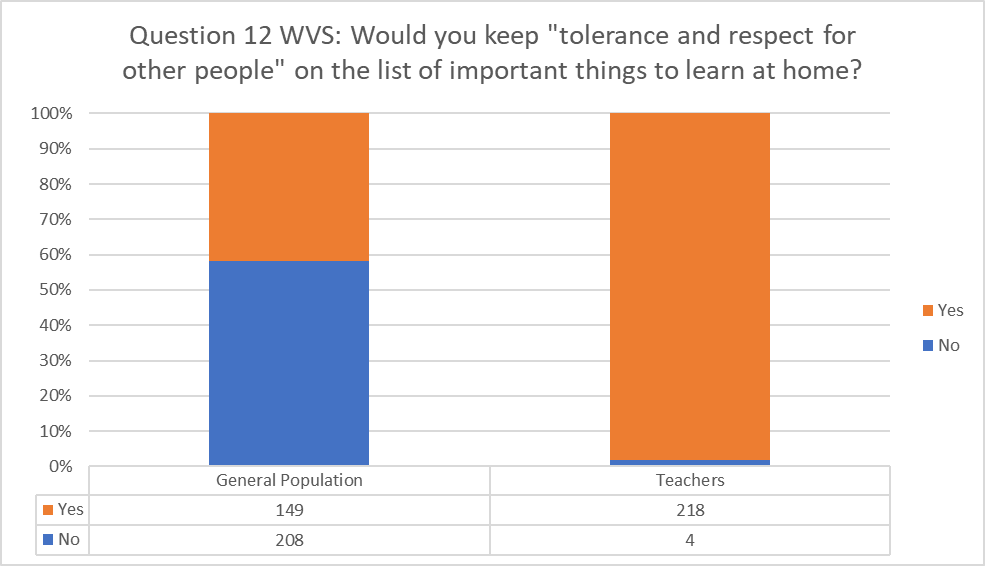

The first question in our research (question no. 21 in the original WVS questionnaire) asked the subjects to answer with ”yes” or ”no” to the following problem: “This is a list of things which children can learn at home: good manners, independence, hard work, feeling of responsibility, imagination, tolerance and respect for other people, thrift, saving money and things, determination (perseverance), religious faith, not being selfish, obedience. If you were to choose only 5 of these, would you keep on this list tolerance and respect for other people?” (We must note that the original question in the WVS asks subjects to choose only 5 items from this list).

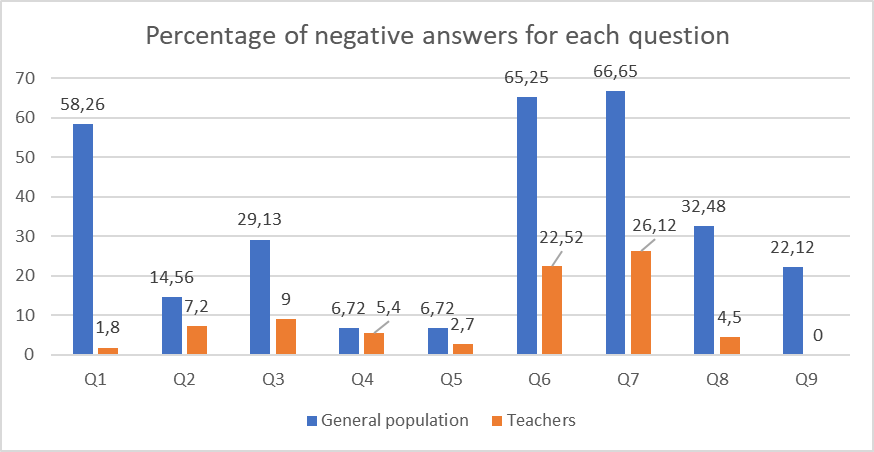

The difference (Figure 2) is overwhelming in favour of the teacher sample for this particular question; while the general population shows a rather balanced proportion of answers (41.8% would keep tolerance on the list, and 58.2% consider that there are other 5 more important traits to be developed at home), teachers are almost unanimously (98.2%) in favour of keeping tolerance on the above mentioned list. One possible explanation for this remarkable difference is the fact that teachers were not forced to choose only 5 elements from the list (a fact which would have dictated them to really rank the importance of those elements). Probably, it is very difficult to reply “no” to such a direct question.

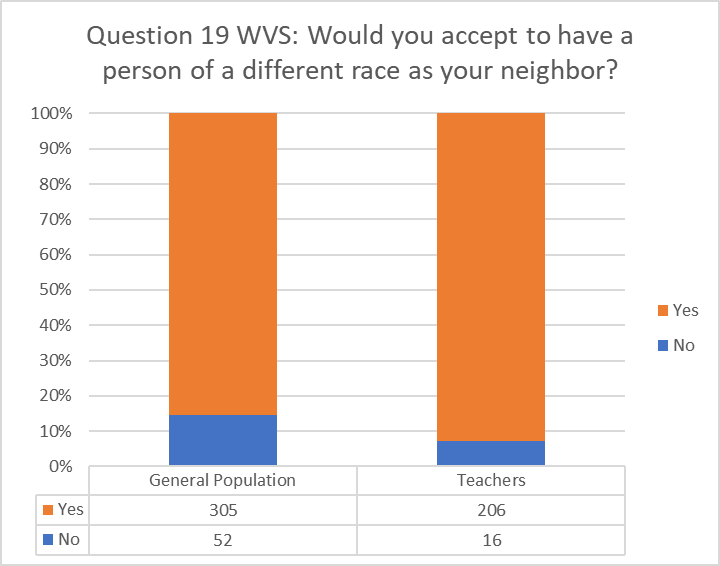

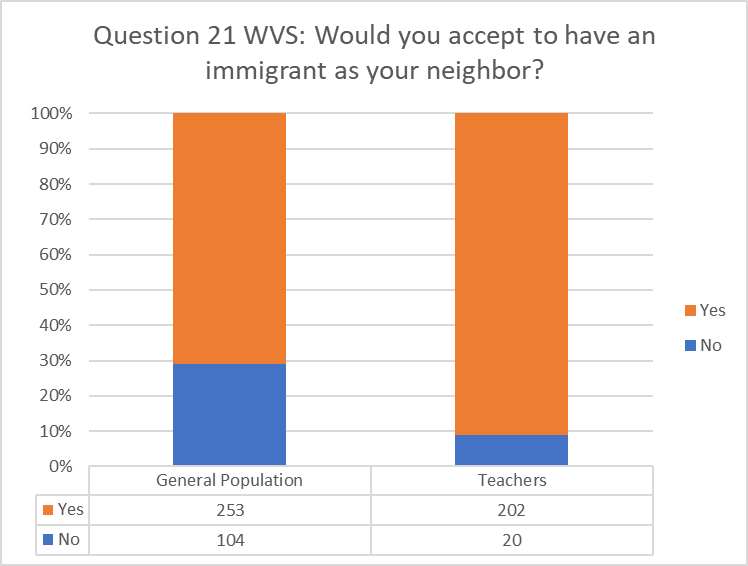

In the original WVS questionnaire, questions 18 to 26 all asked the following: “on this list are various groups of people. Could you please mention any that you would not like to have as neighbours?”. The possible answers were “mentioned” or “not mentioned”. In our questionnaire we chose only 4 of the variants, those tangent with the subject of intercultural openness (questions no. 19, 21, 23 and 26 in the original WVS questionnaire), and we reformulated the questions as: “if you were free to choose your neighbours, would you accept as your neighbour persons of another race / immigrants (foreign workers) / people of other religions / people who speak a different language”. The possible answers were “no” (equivalent with “mentioned”) and “yes” (the equivalent of “not mentioned”). In order to allow the comparison, we changed the answers in the WVS database to the equivalent “yes” or “no”.

In the case of our second question (question 19 in the WVS), 14.56% of the general population was against having a person of a different race as a neighbour, while the teachers who were against this were almost half this value (7.20%), as shown in Figure 3.

Out of the rural teachers, 11.76% were against having a neighbour of a different race, while only 5.19% of urban teachers felt the same. The same analysis regarding the proportion of the general population which was against shows us a very similar 5.21% of urban people versus a much higher 28.08% of rural people. This leads us to the predictable conclusion that the category of rural general population people is the most conservative one.

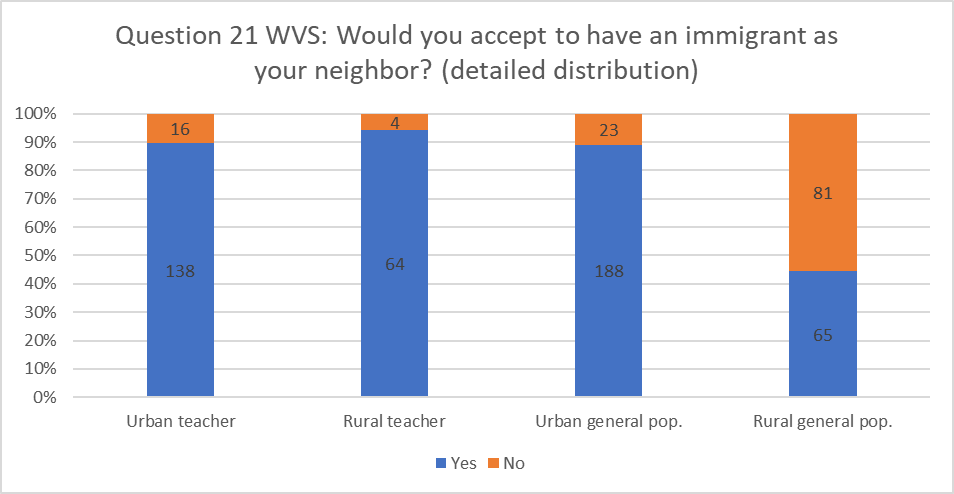

The third question in our study (question 21 in the WVS) investigates the matter of having immigrants or foreign workers as neighbours and the results showed, once again, a much more open attitude towards intercultural experiences from the teacher population compared to the general population; teachers’ “yes vs. no” relationship is 91% vs. 9%, while the general population showed a 70.8% vs. 29.2% report (Figure 4).

The majority of “no” answers belong to the rural general population (Figure 5), confirming the data from the previous question: more than 55% of the general rural population would not accept an immigrant as a neighbour, while the rest of our groups of subjects reach only 5 to 10 percent negative answers. This massive difference might be caused by a severe lack of correct information in the rural environment where even the word “immigrant” bears a negative and possibly threatening significance. A further study should investigate the perception of this word and of the social imagery of immigration in the countryside, in order to reveal what would be the most important to be addressed by educational policies and strategies.

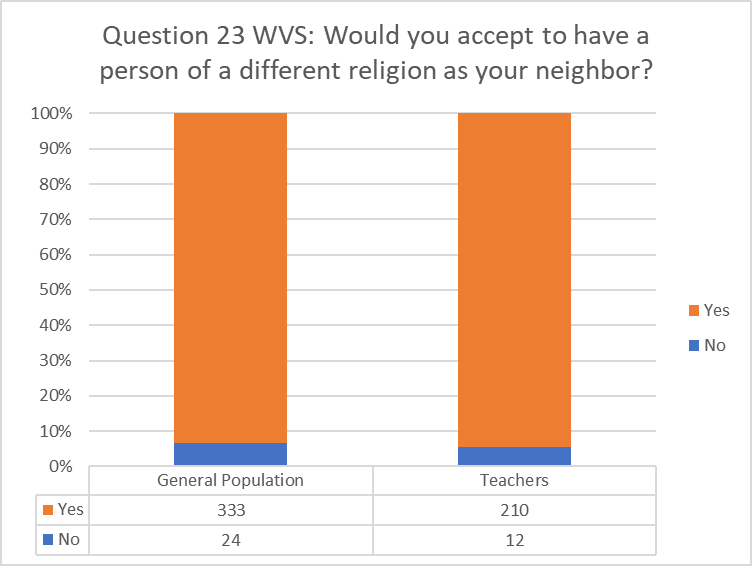

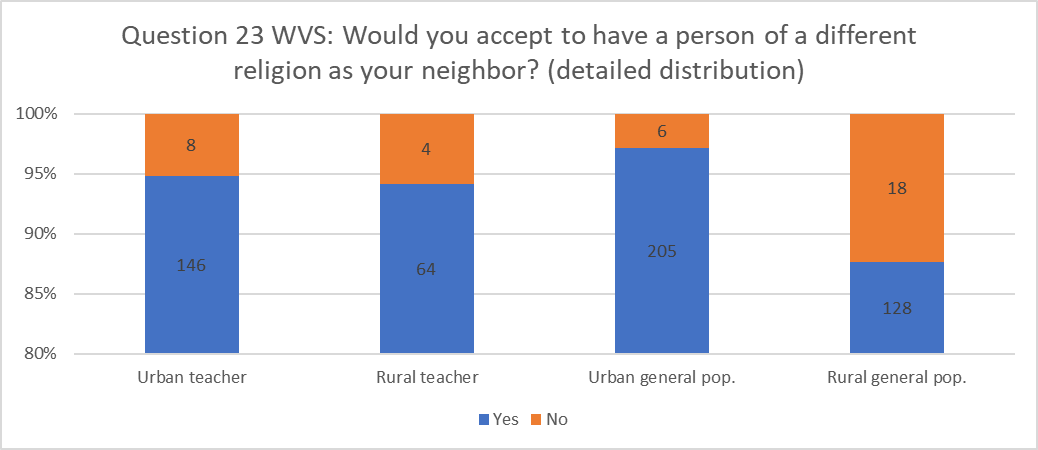

The fourth question in our set (question 23 in WVS) concerns the subjects’ feelings towards people of a different religion and had the same possible outputs. This time, the results were more in the same line: 6.72% of the general population were against having as a neighbour a person of a different religion, and 5.40% of teachers felt the same (figure 6).

If we take into account the urban / rural division, we must note that, in the case of this particular question, the urban general population was more open towards cultural differences than urban teachers (and, obviously, than rural general population or rural teachers): only 2.84% against people of different religions as neighbours, contrasted with 5.19% urban teachers against it (figure 7).

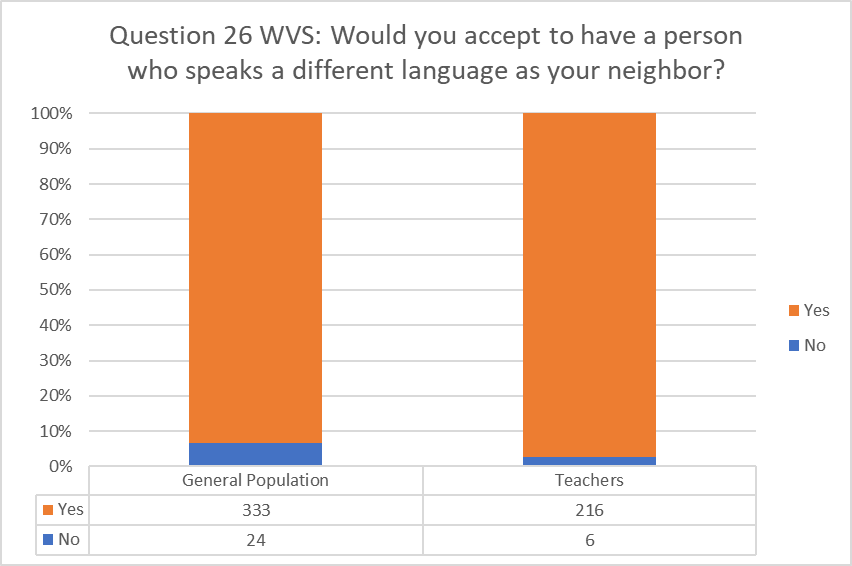

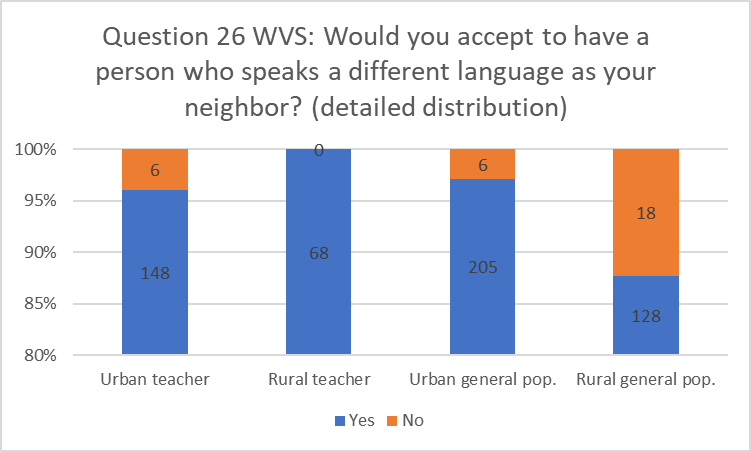

The fifth question in our instrument was the last in the “neighbour paradigm” and investigated the possibility of having as neighbours people who speak a different language than the subjects’ language. Again, the results were visibly in favour of the sample of teachers: 2.70% opposed the idea, while 6.72 of the general population rejected this scenario (figure 8).

We should note that this question was the only one of this set of four questions regarding the possible intercultural neighbourhood which received 0 negative responses from a certain group: the rural teachers (figure 9). Apparently, the difference in languages is literally not important for teachers living in the countryside, probably due to the mixed structure of the population living in these areas. While some villages can be characterized by deeply nationalistic attitudes (paired, sometimes, with traces of xenophobia and chauvinism), other villages in Transylvania have an extremely long history of rather peaceful multiculturalism. Unfortunately, this is a variable almost impossible to control without massive sociological research. Also, if we regard the overall situation of answers (teachers and non-teachers combined) this question receives the least negative answers (5.18% negative answers); this fact might be severely influenced by the deep multicultural environment specific to Western Romania, arguably the most ethnically and culturally diverse historical region of Romania. Here, it is absolutely common to hear multiple languages such as Romanian, Hungarian, Romany, German, Slovak and so on being spoken on the streets, be they in urban or rural environments.

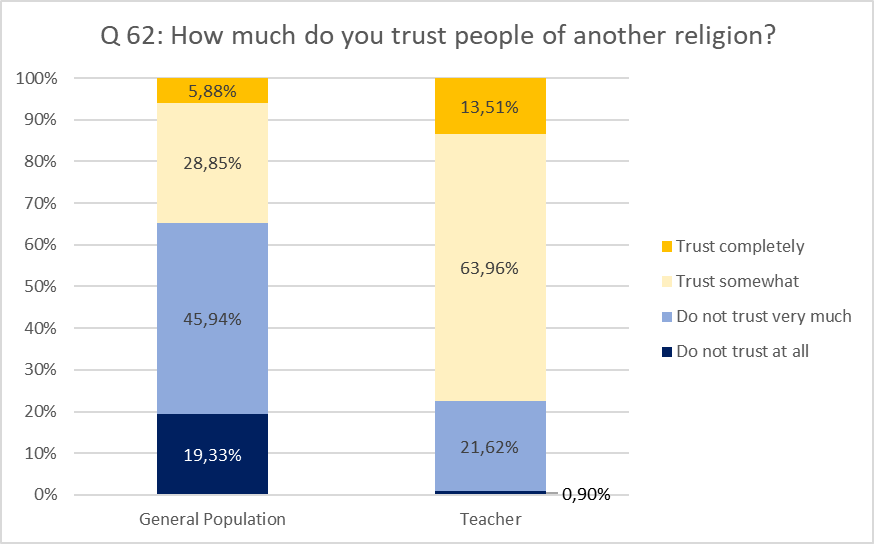

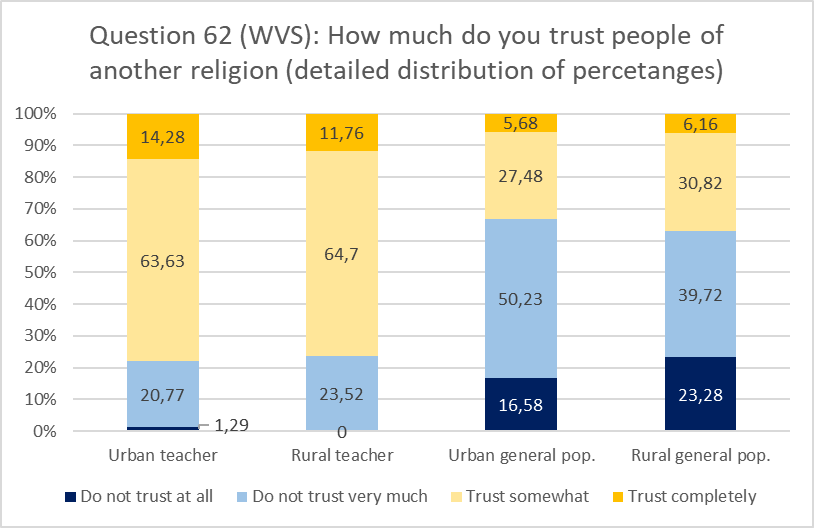

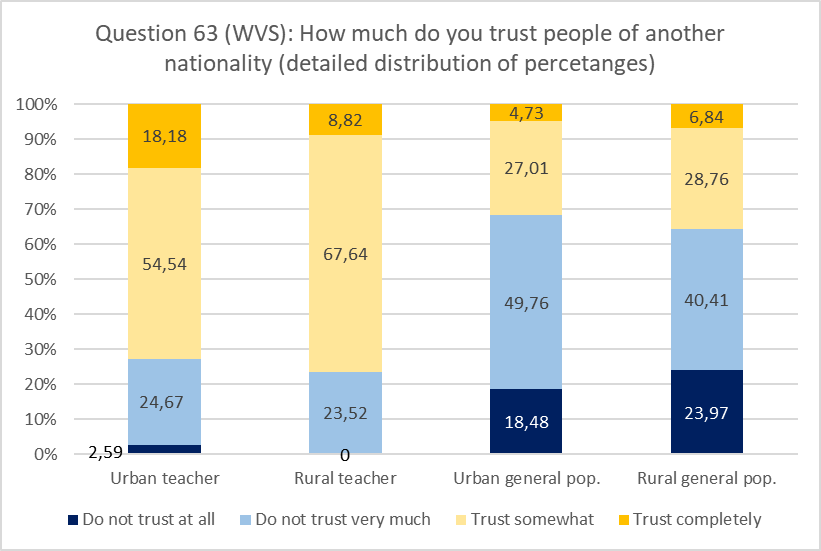

The next two questions in our study were taken from another section of the WVS, the one addressing the issue of trust in people. More precisely, we selected questions no. 62 and 63 in the WVS questionnaire which asked the subjects to assess how much trust they have in people of another religion, respectively people of another nationality. The answers consisted of a 4-point Likert scale: “trust completely”, “trust somewhat”, “do not trust very much”, and “do not trust at all”.

Interpreting the results of this 4-point Likert scale can be done in a blunter way if we group the answers into “positive” and “negative'' categories (the first two answers, respectively the last two possible answers. When presented this way, the results lead to undoubtable conclusions: while the general population reaches 65.27% negative trust, teachers reach only 22.52% for the two negative answers (Figure 10).

A detailed analysis will show that in the case of this question there isn’t a major difference between rural and urban samples, for each category surveyed: the general population shows lower trust, with insignificant difference between urban and rural, while the teacher population shows higher values of trust (again, with insignificant differences concerning the environment). See in Figure 11 the similarities between urban and rural in each case.

The situation is almost identical for the following question (question 63 in the WVS: “How much do you trust people of another nationality?”). While 66.67% of the general population show negative trust (have chosen “no trust at all” or “do not trust very much”), only 26.13% of the teachers show negative trust (see the detailed distribution of answers in Figure 12).

Finally, the set of last two questions were extracted from a subsection of WVS which was concerned with economy related matters; here, we could find some of them addressing the issue of migrants, a topic which we considered to be appropriate for revealing the intercultural openness of our subjects. While theoretically this sounds legitimate enough (and we have to remember the strong negative reaction of rural people against possible immigrant neighbours revealed by question 21), in practice we have to take into account the fact that the immigrants are a very scarce presence in Romania. According to official European data published by Eurostat, Romania ranks last within the European Union regarding the number of immigrants, with immigrants representing only 0.6% of the population. Of these, almost half (40.2%) are Moldavian citizens (extremely similar from many cultural points of view with Romanian citizens, including language), and another 20.1% are Spanish and Italian citizens (of which almost all are, in fact, Romanian citizens which have, at some point in the past, received Italian or Spanish citizenship and, as a consequence, count now as immigrants in Romania). These numbers make us understand that meeting an actual immigrant is actually a very rare opportunity for most Romanians and, from here, having a correct representation of his/her contribution to Romania’s development or culture is very improbable.

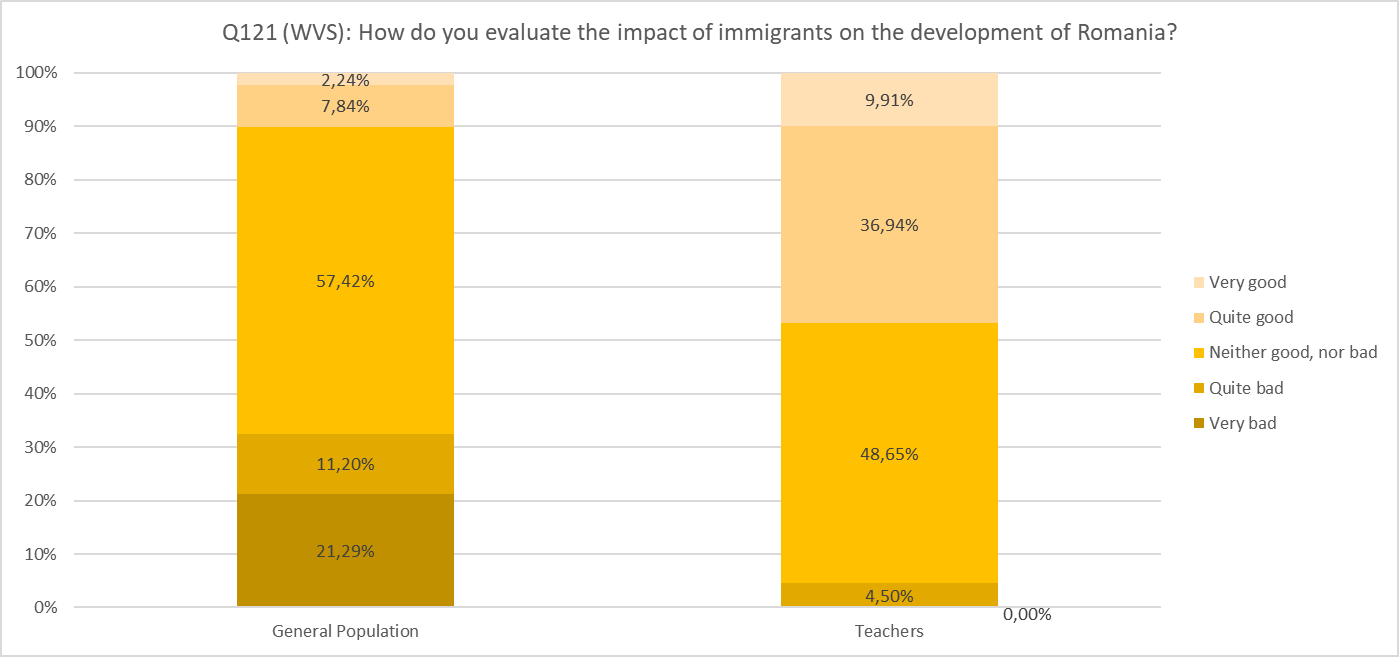

Both of these last questions prove that people find it hard to assess the impact of immigrants in Romania. Question 121 (in the WVS) asked the respondents to evaluate the impact of immigrants on the development of Romania. The answers were laid on a 5-point Likert scale and the vast majority of the subjects in both samples chose the middle of the scale (“neither good, nor bad”), a clear indication of the fact that they do not actually feel the presence of immigrants in Romania (Figure 13). Let us make a short note of the fact that while teachers were hesitant to use the worst answer possible (0 “very bad” answers), the general population placed this answer as its second favourite (21.29%) - which is intriguing since they, most likely, have not actually met an immigrant.

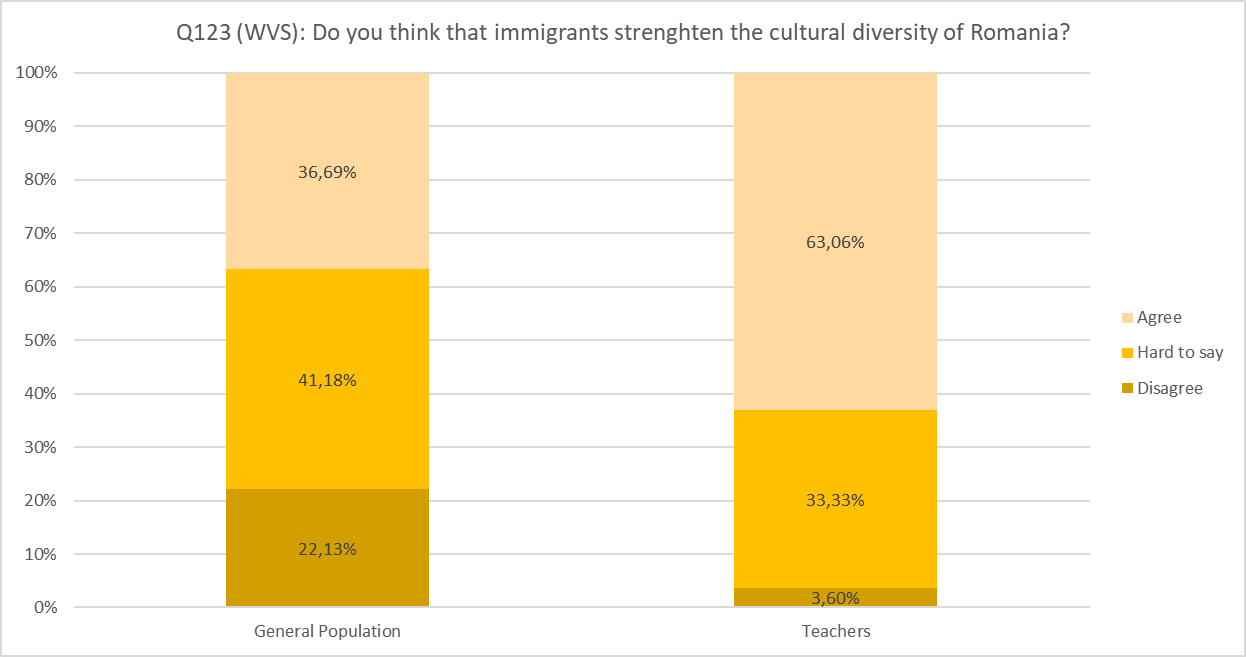

The last question (question 123 in the WVS) was designed to evaluate the impact of immigrants upon the cultural diversity of Romania, with only three possible answers: negative (“disagree”), neutral (“hard to say”) and positive (“agree”). As shown below (Figure 14), teachers showed a positive evaluation of the immigrants’ presence in an almost double amount compared to the general population.

A general analysis of all the answers will provide a clear image of the fact that teachers prove to be, constantly, more interculturally open than the members of the general population (Figure 15).

Conclusions

We set out to find out whether teachers in Western Romania are more progressive or, conversely, more conservative than the average general population. As an axiom, we presumed that one very important mirror of the progressive or conservative mind-sets is people’s intercultural openness in the way that progressive people will show much more of this attribute than conservative ones. In order to compare the general population with the particular category of teachers we chose to use the 7th wave of the World Values Survey questionnaire and database, of which we selected 9 questions with implications for a person’s intercultural openness. Comparing the results gathered from the teacher sample with those of the general population, we can state without a trace of doubt that teachers in Western Romania show a much higher degree of intercultural openness than the general population.

One possible explanation for this difference is the fact that teachers undergo, throughout their careers, a series of goal-oriented transformations caused by formal and informal training programs, workshops, international mobilities and so on, being more exposed to contemporary intercultural paradigms. All of these make the teacher population show higher levels of civic involvement in general (Fitzgerald & Laurian-Fitzgerald, 2017), and intercultural openness in particular. One interesting finding of our study is that comes after the intragroup analysis which takes into account the urban vs. rural division shows that teachers from the rural environment rank significantly lower on the intercultural openness scale, but this is not very surprising since other studies show that this fracture exists in many aspects of the teachers’ mind-sets (Perțe, 2019).

The final conclusion of this study is that the remarks of Claudiu Tufis (2018) are evidently valid: Romanian teachers are, indeed, more open to cultural diversity and more tolerant than the majority of the general population. Further research should investigate specific differences within the teacher population according to regions, age, gender or other variables in order to generate corrective mechanisms and policies for increasing the overall level of intercultural openness in Romania.

References

Badescu, G., Negru-Subtirica, O., Angi, D., & Ivan, C. (2017). Profesor în România. Cine, de ce, în ce fel contribuie la educaţia elevilor în școlile românești? [Teacher in Romania. Who, why, how they contribute to the education of students in Romanian Schools?] Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Catana, L. (2015). Evolution of the teacher's image, From biblical books to the present. In L. Pogolșa, N. Bucun, & N. Vicol (Eds.), Valorile moral-spirituale ale educaţiei: Materialele Simpozionului Pedagogic Internaţional, 3-4 aprilie 2015 [The moral-spiritual values of education. The materials of the International Pedagogic Symposium, 3rd-4th of April 2015] (pp. 75-79). Institutul de Științe ale Educației.

Chircu, E. S., & Negreanu, M. (2010). Intercultural development in the Romanian school system. Intercultural Education, 21(4), 329-339. DOI:

Coulangeon, P. (2017). Cultural openness as an emerging form of cultural capital in contemporary France. Cultural Sociology, 11(2), 145-164. DOI:

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241-266. DOI:

Dilthey, W. (2020). The Essence of Philosophy. University of North Carolina Press.

Fitzgerald, C., & Laurian-Fitzgerald, S. (2017). Teacher citizenship behavior. Education and Applied Didactics, 1(1), 26-35.

Fowers, B. J., & Davidov, B. J. (2006). The virtue of multiculturalism: Personal transformation, character, and openness to the other. American Psychologist, 61(6), 581-594. DOI:

Frumos, F.-V. (2018). Romanian preschool teachers' professional beliefs about diversity. Romanian Journal for Multidimensional Education, 10(4), 105-117. DOI: 10.18662/rrem/76

Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E., & Puranen, B. (Eds.) (2020). World Values Survey: Round Seven – Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid, Spain & Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. DOI:

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: software of the mind. McGraw Hill. DOI:

Indolean, I. (2020). Modele cinematografice româneşti ale tânărului comunist în anii ’80 [Romanian cinematografic models of the young communist in the 80’s]. In V. Țârău (Ed.), Ipostaze ale tinereţii în România comunistă [Instances of youth in Communist Romania]. Argonaut Publishing House.

Kiss, J. F. (2020). Educational policies in relation to society, students and teachers. Journal of Teacher Training and Education Research, 1(1), 43-50.

Maci, M. (2018). Declasarea profesorimii române [The declassification of Romanian teachers]. In M.-A. Georgescu (Ed.), 100 de ani de invatamant. Perspectivele educatiei in urmatorii 100 de ani in Romania [100 years of teaching. The perspectives of education in the next 100 years in Romania]. Hamangiu Publishing House.

Mara, D. (2021). Intercultural competences of students-strategic approaches. MATEC Web of Conferences, 343, 11003. DOI:

Middendorp, C. (2019). Progressiveness and conservatism. The fundamental dimensions of ideological controversy and their relationship to the social class. De Gruyter Mouton. DOI:

Niculescu, R. M., & Bazgan, M. (2017). Intercultural competence as a component of the teachers' competence profile. Romanian Journal for Multidimensional Education, 9(3), 17-41.

Perțe, A.-M. (2019). Job Satisfaction And Self-Esteem For Primary School And Kindergarten Teachers. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences DOI:

Sdrobiș, D. (2015). Limitele meritocraţiei într‑o societate agrară: şomaj intelectual şi radicalizare politică a tineretului în România interbelică [The limits of meritocracy in an agrarian society: intellectual unemployment and political radicalization of youth in interwar Romania]. Polirom Publishing House.

The Ministry of Education. (2021, April 5). The number of teachers in each county [data file]. https://data.gov.ro/dataset/numar-cadre-didactice-preuniversitar-per-grad-didactic-in-anul-scolar-2019-2020

Tufis, C. (2018, October 18). Profesorii sunt doar o oglindă a populației, puțin mai lustruită [The teachers are just a mirror of population, a bit more polished]. Avocatnet. https://www.avocatnet.ro/articol_49616/Profesorii-sunt-doar-o-oglinda-a-populatiei-putin-mai-lustruita.html

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

10 April 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-961-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

5

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1463

Subjects

Education sciences, teacher education, curriculum development, educational policies and management

Cite this article as:

Pătroc, D. (2023). Are Teachers Better Than Other People? The Intercultural Openness of Romanian Teachers. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues - EDU WORLD 2022, vol 5. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 1094-1108). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23045.110