Abstract

Responsible consumers act collectively with integrity and resilience. Empowering responsible consumers through ta’awun (mutual cooperation) enables sustainability in consumption. This study aims to explore the roles of ta’awun (mutual cooperation) among consumers in a society of responsible consumers. The study used personal interviews with consumer activists. The personal interviews with consumer activists argued that empowering responsible consumers through ta’awun (mutual cooperation) for sustainability can be done based on workable and practical mutual cooperation leads to good outcomes. The process is monitored and evaluated with willingness, ability, and piety. Responsible consumerism is intensified with mutual cooperation and the attitude of being socially responsible and sustainable. The taqwa-driven ta’awun (mutual cooperation) with responsible consumption sustainability can be done through education and awareness campaigns, providing access to sustainable goods and services, and establishing incentives for businesses to adopt more sustainable practices. For future research, the personal interview can be extended to policymakers and other civil society advocates.

Keywords: Responsible consumption, sustainability, Ta’awun (mutual cooperation)

Introduction

Responsible consumption is one of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Consumers have responsibility for their consumption. Goal Number 12 of the Sustainable Development Goal is to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns (Carlsen & Bruggemann, 2022; UNDP, 2015; Warde, 2015). There are many reasons for responsible consumption (Abdul Razak, 2021; Blum et al., 2021; Frenken, 2017; Said & Hikmany, 2016).

First and foremost is to save money. A responsible consumer who is very careful and responsible about consumption could save money in the long run by avoiding overspending and buying only what is necessary (Abdul Razak, 2021; Huang & Rust, 2011; McNeill, 2023). In addition, a responsible consumer can have to protect limited and precious resources (Jalil et al., 2020; Warde, 2015). This is logical when a consumer consumes responsibly, each consumer could reduce the negative impact on the environment (climate change) and protect natural resources for future generations.

Subsequently, a responsible consumer could enjoy a good and healthy life by eating healthy foods, quitting smoking, and exercising regularly are not only improving physical health but also mental well-being (Balaji et al., 2022; McNeill, 2023; Venkatesan et al., 2022; Webb et al., 2008). Thus, responsible consumers would make a difference in their livelihood when every time a consumer buys something or makes an economic decision, each of them has the power to support companies with ethical practices or those that use sustainable materials and production methods to reduce their environmental footprint (McNeill, 2023; Tsen, 2021; Venkatesan et al., 2022). In the long run, responsible consumption promotes economic equality by supporting small businesses and local producers, who often rely on fair trade practices to ensure that all workers are treated fairly and compensated adequately for their work (Balaji et al., 2022; Jalil et al., 2020; Webb et al., 2008). Hence, responsible consumption leads to a meaningful life by being mindful of the choices made and how each choice affects the community, environment, and future generations.

There is a need for the policy to support sustainable consumption. A responsible consumption policy allows for the authority to establish regulations (Antil, 1984; Paterson, 2017; Sassatelli, 2007). Consumer affairs authorities in the governments can create regulations that encourage responsible consumption by setting limits on the amount, type, and quality of products or services consumed (Balaji et al., 2022; McNeill, 2023; Venkatesan et al., 2022; Webb et al., 2008). This could include laws to regulate the production, sale, and use of certain goods or services. It also enables educational function by encouraging education and public awareness.

Policy implementation via government agencies could promote public awareness campaigns that educate citizens about the environmental impacts associated with irresponsible consumption practices. These campaigns can help individuals understand how their choices affect the environment around them so they can make more informed decisions when it comes to their purchasing habits (Abdul Razak, 2021; Blum et al., 2021; Frenken, 2017; McNeill, 2023; Tsen, 2021). A policy not only educates citizens but also reinforces good behavior by providing incentives for responsible consumption to responsible consumer citizens.

Governments should provide incentives to businesses and consumers who demonstrate responsible consumption behaviors such as using renewable energy sources or buying sustainable products. This could include tax breaks, subsidies, or other financial incentives (Abdul Razak, 2021; McNeill, 2023). In addition, a policy should also support sustainable consumption practices via funding and resources to help businesses develop sustainable consumption practices such as using renewable energy sources or adopting green technologies. This could include grants, loans, and other forms of financial assistance.

Consumer education is essential to encourage more educated consumers. There are some reasons for consumer education (Abdul Razak, 2021; McNeill, 2023). Firstly, it is to promote financial responsibility. Consumer education helps individuals understand the implications of their financial decisions and enables them to make responsible choices (Tsen, 2021). Secondly, it is to protect consumers from fraud and abuse. Educating consumers are on how to identify, avoid, and report fraud can help protect them from becoming victims of scams or other unfair practices by businesses (Jalil et al., 2020). Thirdly, it is to increase awareness of products and services. By teaching consumers about available products and services, they are better able to choose those that best suit their needs while avoiding inferior or unnecessary options. Next is to encourage savings. Teaching individuals the importance of saving money for future purchases can help them build a strong financial foundation that will serve them well as they age. Finally is to educate consumers on rights and responsibilities. Understanding their rights as consumers can help individuals make informed decisions when purchasing goods or services while understanding their responsibilities can ensure they fulfil obligations to businesses.

Approaches for consumer education can be done via financial education programmes, financial literacy campaigns, and community outreach programmes (Abdul Razak, 2021; McNeill, 2023). In the financial education programmes, many organizations could offer sponsored, free, or low-cost financial education programmes for people of all ages and backgrounds to increase consumer knowledge of personal finance concepts and strategies (Tsen, 2021). These programs often include seminars, workshops, classes, webinars, videos, and other types of instruction that teach participants how to better manage their money and build wealth over time (Barnett et al., 2005; Trentmann, 2004). In addition, there can be financial literacy campaigns. Many organizations could provide education for financial literacy (Jalil et al., 2020). These campaigns are designed to help people understand key concepts related to budgeting, saving, investing, credit management and more. In a long term, there can be community outreach programmes. There are banks, cooperatives, money lenders and other local organizations that could offer community outreach programs aimed at educating consumers about personal finance topics. These programmes often involve providing free seminars or workshops in local schools or libraries that cover a range of financial topics relevant to people of all ages and backgrounds.

The academic challenge to the study of responsible consumption is how to strike a balance between theoretical development in the responsible consumption (theories that underpinned it) and the immediate policy outcomes expected from the SDGs (2015-2030). The theories that underpinned consumerism studies include (a) social exchange theory, (b) cognitive dissonance theory, and (c) motivation theories. Social exchange theory suggests that consumers make decisions based on a cost-benefit analysis, weighing the perceived benefits of a purchase against its cost and any potential risks or drawbacks (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Chen & Sriphon, 2022). The cognitive dissonance theory proposes that people seek to reduce the amount of cognitive dissonance they experience by making choices that are consistent with their beliefs and values (Cooper, 2012; Frindte & Frindte, 2023; Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones, 2003). The motivation theories explain how motivation influences consumer behaviour by suggesting that consumers’ needs and wants drive their buying decisions (Acquah et al., 2021; Egberi, 2020; Munir, 2022). For example, Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs explains that individuals satisfy basic needs before seeking more complex ones such as self-actualization or social recognition through consumption behaviours like shopping for luxury goods.

In contrast, the theories underpinning sustainable development studies include (a) change theory, (b) ecological modernization theory, (c) sustainable development theory, (d) ecosystem services theory, and (e) resilience thinking theory. The change theory is a formal method of understanding how people, systems, and organisations adapt to change. It involves recognising patterns in the way that change occurs, then applying strategies to manage it effectively (Burnes, 2020; Hussain et al., 2018). The change theory also focuses on anticipating potential issues before they arise, as well as developing plans for dealing with them when they do occur (Burnes, 2020). The goal of this approach is to create an environment where positive changes can be implemented quickly and efficiently while minimizing disruption. In addition, ecological modernization theory that embedded in sustainable development studies suggests that economic development can be reconciled with environmental protection and conservation by introducing more efficient technologies and processes (Buttel, 2000; Bugden, 2022; Kachynska et al., 2022). The specific theory to the sustainable development, which is sustainable development theory, proposes that economic growth must be balanced with social equity and environmental protection in order to achieve sustainability for future generations (Ferreira & Valdati, 2023; Lin et al., 2022; Ogryzek, 2022). Likewise, the ecosystem services theory posits that ecosystems provide essential services like carbon sequestration, water filtration, food production, etc., which are important components of sustainable development efforts (Costanza, 2016). Resilience Thinking Theory emphasizes the importance of building resilience into systems so they can better adapt to changing conditions while maintaining their core functions over time (Chandler, 2019; Masnavi et al., 2019; McKeown et al., 2022).

This study uses ta’awun (mutual cooperation) concept to harmonize the major theories that underpinned responsible consumerism and sustainability studies. Thus, this study postulated that the significant roles of ta’awun (mutual cooperation) among consumers empower a society of responsible consumers. Essentially, the objective of the study is to explore the roles of ta’awun (mutual cooperation) among consumers to empower for a society of responsible consumers.

Literature Review

Responsible Consumption

Consumption is an act of using a resource. It is a complex social situation when consumers consume goods and services. It is also a process of buying or using goods and services. Responsibility in consumption lies in the state of dealing with or having control over something (Abdul Razak, 2021; Blum et al., 2021; Frenken, 2017).

When a consumer decided to buy and consumer goods or services, the consumer has taken a duty to accept the goods and services. The responsibility in consumption is mutual and reciprocal. The logic is in the transaction of buying and selling (Balaji et al., 2022; McNeill, 2023; Venkatesan et al., 2022; Webb et al., 2008). When a seller offers a product to a buyer, the seller has secured informed consent from the buyer. The use of the goods is based on the information provided by the seller. In any situation when the buyer is not getting the benefit of the product, the buyer can claim back from the seller. If there is a dispute, then there is a need for a mediator from the government.

Empowerment

Empowerment is the process of giving individuals or groups the authority, resources, and support to make decisions, take action, and accomplish change. It involves increasing the capacity of individuals or communities to gain control over their own lives and destiny by enabling them to make informed choices (Brieger et al., 2019; Harmsen, 2008; Herrmann, 2012). Empowerment is a process that increases self-determination and creates an environment where people can realise their full potential (Herrmann, 2012; Malian & Nevin, 2002; McNaughtan et al., 2022). Empowerment for consumers enables individual consumers and institutionalized consumers to increase activism satisfaction, improve service delivery, be creative and innovative, increase productivity, and be efficient.

When consumers are empowered, they can enjoy responsible consumption satisfaction. Responsible consumer empowerment is that it increases consumer activism satisfaction and motivation, leading to better performance (Herrmann, 2012; Malian & Nevin, 2002; McNaughtan et al., 2022). Empowered consumers can improve service delivery in terms of consumerism education and campaigns. They can make decisions quickly and efficiently. Empowered consumers also can be creative and innovative with new ideas or solutions that may not have been considered before. Thus, this can increase productivity and efficiency.

Theories that underpinned empowerment provide a framework for understanding how people can gain control over their lives, achieve self-determination and make positive changes. These theories encompass concepts such as power dynamics, social justice, personal autonomy, collective action, and the role of institutions in enabling or constraining individual potential (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995; Wilkinson, 1998; Zimmerman, 2000). They also emphasise the importance of creating an environment that is conducive to meaningful engagement with others in order to realize shared objectives. In addition to providing a conceptual foundation for promoting empowerment, these theories help inform strategies for implementing policies and programmes that support individuals’ capacity to exercise agency in their own lives.

Ta’awun (mutual cooperation)

Mutual cooperation is a relationship between two or more parties in which all involved recognise and agree to work together for mutual benefit. It involves sharing resources, knowledge, and responsibilities to achieve common goals (Dorrough et al., 2022; Lust, 2022; Yuhertiana et al., 2022). Mutual cooperation requires open communication, respect, trust, and accountability from everyone involved to be successful (Dorrough et al., 2022; Lust, 2022). There are many reasons for mutual cooperation, namely to share goals, to gain efficiency, to have synergy, to establish strong communication, and to get together for innovation and creativity.

Mutual cooperation is often based on the shared goals of two or more parties. Working together allows them to pool their resources and knowledge to achieve a common objective. The ability to share goals will lead to greater cooperation which can be beneficial because it increases efficiency by reducing duplication of effort and allowing for the specialisation of tasks (Galegher et al., 2014; Lust, 2022; West et al., 2008). This can help both parties save time, money, and resources while still achieving their goals faster than they would have alone (Dorrough et al., 2022; West et al., 2008). More importantly, when different entities work together, they can create a synergistic effect that produces greater results than either party could have achieved independently. This makes mutual cooperation an attractive option for many organizations looking to maximise their potential output with minimal input costs. The efficiency gained through a strong communication channel between two or more entities is key to successful cooperation. This helps foster trust, understanding, and collaboration that can lead to positive outcomes for both sides of innovation.

Mutual cooperation among members can be reinforced when members are given clear expectations, allow for open communication, foster collaboration at all times, recognise accomplishments, provide incentives, and promote teamwork spirit (Dorrough et al., 2022; Lust, 2022). There is a need to establish clear expectations for members. This can be done by creating a set of rules and expectations that all members must agree to adhere to in order to foster cooperation among them. In doing so, there is a need to encourage open communication, for example, the team can set up a forum, or discussion board where team members can communicate openly about their ideas and concerns (Dorrough et al., 2022; West et al., 2008; Yuhertiana et al., 2022). This will help create an atmosphere of trust and transparency, which is essential for successful teamwork. Successful teamwork is always encouraging collaborative problem-solving by providing opportunities for team members to work together on projects or tasks related to the group's mission or goals. In the meantime, make sure each member is recognised when they contribute something valuable or achieve success as part of the group effort, such as completing a task before the deadline or finding a creative solution to a problem. The provision of incentives is necessary to energise and sustain the motivation of the members.

Ta’awun and Empowerment

Empowerment allows for independence in making decisions for high-impact outcomes. This is a manifestation of vicegerency of human (Alatas, 2014; Mahyudi, 2016; Mahyudi & Aziz, 2017; Omercic et al., 2020; Rakhmat, 2022). The empowerment is guided with the five principles of human existence or maqasid al-shari’ah, namely ‘aqidah (faith), nafs (life), ‘aql (intellect), nasb (lineage), and mal (wealth) (Auda, 2008; Chapra et al., 2008; Dusuki & Abdullah, 2007; Shabbir, 2020).

The actionable verbs that integrate the five maqasid al-shari’ah require ta’awun (Mhd. Sarif et al., 2022a). Ta’awun (mutual cooperation) is spiritually driven mutual cooperation in attaining al-birr (righteousness) and taqwa (piety) (Mhd. Sarif & Ismail, 2022). Taqwa is an Islamic term often translated as “God-consciousness” or “piety” which refers to the practice of being conscious and aware of God at all times (or Tawhidic) and living in a way that is Pleasing Him (Mhd. Sarif et al., 2022a). It encompasses all aspects of life, from personal behaviour to social interactions (Mhd. Sarif et al., 2022b; Zainudin et al., 2021).

There are a few dimensions of taqwa (Mhd. Sarif, 2020, 2021; Tuerwahong & Sulaiman, 2019). Taqwa of Allah is the highest form and involves fear, respect, obedience, and submission to Allah's commands in all aspects of life. Then, the taqwa of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), involves following the teachings and example set by Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) in every aspect of life (Djasuli, 2020; Fontaine, 2022).

Subsequently, it is taqwa towards oneself. This type focuses on avoiding anything that may lead to sin or disobedience against Allah such as backbiting, lying, cheating, and so on (Fontaine, 2022; Mhd. Sarif, 2020; Tuerwahong & Sulaiman, 2019). It also includes controlling one’s desires and passions so they do not become a source for committing sins or wrongdoings against others. Not to forget is the taqwa towards other people (Djasuli, 2020; Fontaine, 2022; Sulaiman et al., 2022). This type of taqwa involves treating others with kindness and respect, fulfilling one’s obligations to them, being just in dealings and transactions, maintaining good relationships, avoiding backbiting or slander, and so forth.

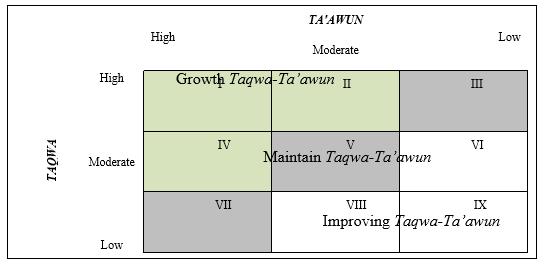

Based on the different levels of taqwa (piety) and ta’awun (mutual cooperation), it can be described as growth taqwa-ta’awun (when taqwa and ta’awun levels are in Cells 1, II and IV), maintain taqwa-ta’awun (taqwa and ta’awun are in Cells III, V, VII), and improving taqwa-ta’awun (in Cells VI, VIII, and IX). Figure 1 depicts the different levels of taqwa (piety) and ta’awun (mutual cooperation) in nine-cell matrix.

Sustainability

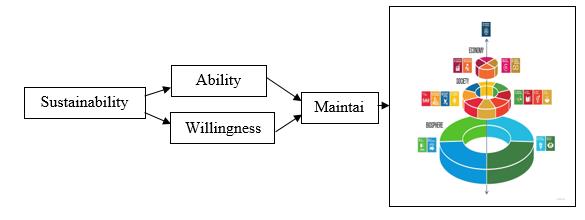

Sustainability is the ability and willingness to maintain a certain level of economic, social, and environmental well-being over time. It involves making decisions that balance short-term needs with long-term consequences in order to ensure that future generations can access the same resources and services as current generations (Abdul Razak et al., 2013; Abdul Razak, 2021; Affolderbach, 2022; Vogt & Weber, 2019). Sustainability is important because it helps to ensure that our planet remains healthy and habitable for future generations (Abdul Razak, 2021; Rieckmann, 2017). Figure 2 shows the relationships between sustainability with ability and willingness.

By living sustainably, we can reduce our impact on the environment, conserve natural resources, minimize pollution and waste production, and help create a more equitable society (Abdul Razak, 2021; Blum et al., 2021; Frenken, 2017). Additionally, sustainable practices can save money in the long run by reducing energy costs and increasing efficiency (Blum et al., 2021; Frenken, 2017).

Consumption sustainability is the practice of consuming goods and services in a way that minimizes their environmental impact. This includes reducing, reusing, and recycling as much as possible; buying products made with sustainable materials; sourcing local goods whenever possible; choosing energy-efficient appliances and electronics; avoiding single-use items like plastic bottles or bags; conserving water; eating less meat and more plant-based foods (Abdul Razak, 2021; Blum et al., 2021; Frenken, 2017).

Consumption sustainability is important because it helps to reduce our negative impact on the environment and conserve natural resources (Abdul Razak, 2021; Huang & Rust, 2011; McNeill, 2023). By making sustainable choices in our everyday lives, we can help ensure that future generations have access to the same resources and services as current generations (Abdul Razak, 2021; Frenken, 2017). Additionally, sustainable consumption practices can save money in the long run by reducing energy costs and increasing efficiency.

Consumption sustainability can be achieved by reducing, reusing, and recycling as much as possible; buying products made with sustainable materials; sourcing local goods whenever possible; choosing energy-efficient appliances and electronics; avoiding single-use items like plastic bottles or bags; conserving water; eating less meat and more plant-based foods (Abdul Razak, 2021; Huang & Rust, 2011; McNeill, 2023). Additionally, it is important to educate ourselves on the environmental impact of our consumption choices to make informed decisions that promote sustainability.

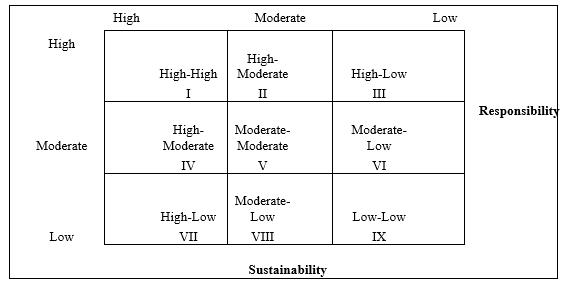

The relationships between sustainability and responsibility can be depicted as high-moderate-low for responsibility and sustainability. There are nine cells to depict different levels of responsibility for sustainability. The highest level is in the Cell 1 (high-high) the lowest is in the Cell IX (low-low). Figure 3 shows the responsibility-sustainability matrix.

Some of the challenges faced when trying to achieve consumption sustainability include changing consumer behaviour and attitudes, lack of access to sustainable products or services, lack of awareness about the environmental impacts of our consumption choices, and economic constraints (Abdul Razak, 2021; Huang & Rust, 2011; McNeill, 2023). Additionally, it is important to consider how different cultures view sustainable practices to ensure that they are implemented in a culturally sensitive way.

Responsible consumption sustainability is the practice of consuming goods and services in a way that minimizes their environmental impact while taking into account social, economic, and cultural considerations (McNeill, 2023; Venkatesan et al., 2022; Webb et al., 2008). This includes reducing, reusing, and recycling as much as possible; buying products made with sustainable materials; sourcing local goods whenever possible; choosing energy-efficient appliances and electronics; avoiding single-use items like plastic bottles or bags; conserving water; eating less meat and more plant-based foods. Additionally, it is important to be mindful of our consumption choices to ensure that they do not have negative impacts on vulnerable communities or ecosystems.

Encouraging responsible consumption sustainability can be done through education and awareness campaigns, providing access to sustainable goods and services, establishing incentives for businesses to adopt more sustainable practices, and creating legislation that requires companies to use more environmentally friendly materials (Balaji et al., 2022; McNeill, 2023; Venkatesan et al., 2022; Webb et al., 2008). Additionally, it is important to consider how different cultures view sustainable practices to ensure that they are implemented in a culturally sensitive way.

Based on the critical review of the literature on the major theories that underpinned responsible consumerism and empowerment, the study harmonized the theories with ta’awun (mutual cooperation) concept. Table 1 provides the summary of the harmonisation of major theories in empowerment for responsible consumerism with ta’awun concept.

Based on the harmonization process, the study postulated the research framework of empowering responsible consumers through (mutual cooperation) for sustainability with several variables. The variables are empowerment, responsible consumers, sustainability and (mutual cooperation). Figure 4 depicts the framework of the research.

Research Methods

This study uses qualitative research through personal interviews with consumer activists. This research paradigm is in line with the objective of the study is to explore the roles of ta’awun (mutual cooperation) among consumers and empower a society of responsible consumers. The step-by-step action undertaken to conduct qualitative research with the personal interview method is based on Silverman (2020). Firstly, developing a research question. This step is done after a thorough literature review. From the research question, the study developed interview questions. The study approached two independent researchers to review and validate the research question and interview questions together with the research protocol. The researchers also secured research permission of the research management centre.

Secondly, selecting the informants for the research. The selection was based on the researchers contact among consumerism activists. To avoid self-biasness, the researchers sought the two independent researchers about the selected informants. Thirdly, preparing for the interview. The researchers created an interview guide, which is a set of questions or topics intended to keep the conversation on track and focused on specific areas of interest; practice asking them out loud; and prepare any necessary materials such as recording equipment or consent forms for each participant to sign before beginning the interview.

Fourthly, conducting the personal interviews. The researchers secured informed consent, and then scheduled an appropriate time with each informant. The researchers explained that they are conducting the interview and asked to sign a consent form. The researchers also explained the purpose of each question that they planned to ask and assured the informants understood it before proceeding. Immediately after each interview, the researchers requested the informants to verify the interview notes. Fifthly, analyzing the data after all the interviews have been conducted, reviewing the notes from each session and looking for themes or patterns that may help answer the research questions. Finally, reporting the findings. At this stage, the researchers summarized the key insights they uncovered through their interviews in a report or presentation that can be shared with stakeholders and other interested parties.

The researchers used a manual note-taking approach. Each interview took 30-45 minutes. The researchers used triangulation to validate the interview results (Anderson, 2010; Flick, 2019). Immediately after the interview, the researchers transcribed the interview notes into readable transcripts. The informants were asked to validate the interview transcripts (Anderson, 2010; Silverman, 2020).

The researchers corrected the interview transcripts as pointed out by the informants. Next, the researchers approached two independent qualitative researchers who are familiar with the context of the research to verify the validated interview transcripts (Flick, 2019; Silverman, 2020). The researchers used thematic content analysis to analyze the validated interview transcripts. The use of themes allowed the researchers to ground themes from the feedback of the informants.

Findings and Discussion

This section presents the findings from the personal interviews with consumer activists. This research paradigm is in line with the objective of the study is to explore the roles of (mutual cooperation) among consumers and empower a society of responsible consumers. The informants were asked two interview questions, namely (a) what is your view about having mutual cooperation among consumers?, and (b) How could consumers cooperate based on mutual cooperation?

Views on mutual cooperation

The following are the findings from the first interview question to three informants (what is your view about having mutual cooperation among consumers?).

Mutual cooperation among consumers is ideal but workable. According to Consumer Activist 1, there are more benefits when consumers could have mutual cooperation. Consumer Activist 1 said:

"I have more than 20 years in the consumerism movement and I believe that mutual cooperation (if you can say so) among consumers is a great way to ensure better access to goods and services. But, be mindful that in reality, not all consumers can work together. Ideally, when consumers are working together, there can be a more efficient use of resources, as consumers can share information about products, prices, and quality. This type of cooperation encourages competition between businesses to provide the best possible service or product at a competitive price. In addition, it helps build trust between consumers and businesses which can lead to improved customer satisfaction."

Workable mutual cooperation is imbued with high willingness, ability, and piety (Fontaine, 2022; Mhd. Sarif, 2020; Mhd. Sarif et al., 2022a; Tuerwahong & Sulaiman, 2019). Then, activists of responsible consumerism mutually cooperated with the attitude of socially responsible and sustainable (Abdul Razak, 2021; Balaji et al., 2022; Djasuli, 2020).

Echoing Consumer Activist 1, Consumer Activist 2 pointed out the practicality of mutual cooperation. Consumer Activist 2 mentioned:

“I am a practical person. You don't need a very sophisticated idea to explain this. I believe that cooperation among consumers is beneficial to both parties. It increases the level of competition between businesses, which can lead to better prices and quality products or services. It also encourages a sense of trust between consumers and businesses, leading to improved customer satisfaction. Cooperation among consumers can help ensure that everyone has access to goods and services at a fair price, creating an equitable marketplace for all involved.”

Practicality is in the economic, social and environmental senses (Abdul Razak, 2021; Huang & Rust, 2011; McNeill, 2023) that are guided by taqwa (piety) (Fontaine, 2022; Mhd. Sarif, 2020, 2021; Tuerwahong & Sulaiman, 2019) and sustainability (Abdul Razak, 2021).

Mutual cooperation can lead to good outcomes. However, Consumer Activist 3 is skeptical. Consumer Activist 3 uttered:

“Humans are not naturally wanted to work together. Only if they could benefit from working together. I think it is a positive thing for consumers to work together for their own benefit. When consumers cooperate and share information, they can gain access to better prices, quality products or services, and more efficient use of resources. This type of cooperation also encourages competition between businesses, which helps ensure that everyone has access to goods and services at fair prices. Working together for mutual benefit helps create an equitable marketplace where all participants have equal opportunities.”

A workable and practical mutual cooperation leads to good outcomes that are qualified by high willingness, ability, and piety (Fontaine, 2022; Mhd. Sarif, 2020; Mhd. Sarif et al., 2022a; Tuerwahong & Sulaiman, 2019). Ultimately, responsible consumer activists intensified mutual cooperation with the attitude of socially responsible and sustainable (Abdul Razak, 2021; Balaji et al., 2022; Djasuli, 2020).

In short, empowering responsible consumerism through mutual cooperation among consumers requires a workable idea that can be practical to give mutual benefits and greater good outcomes.

Basis of mutual cooperation

The following are the findings from the second interview question to three informants (how could consumers cooperate based on mutual cooperation?).

Consumers can have mutual cooperation among themselves if they have the willingness and readiness to do so. Consumer Activist 1 said:

“If you have a will, you will have the way to do anything. In my own experience and observation, I think consumers can cooperate among themselves in many ways. They can share resources, such as cars, tools and other items that they may not need all the time but could benefit others. Consumers can also organize to create collective buying power or support local businesses and producers. Additionally, they can come together to advocate for their interests with governments or companies through campaigns or protests. Finally, consumers can work together to promote sustainable practices by encouraging recycling programs and reducing energy consumption.”

However, Consumer Activist 2 argued that there is a need to have an advocate among consumers to call for mutual cooperation. Consumer Activist 2 mentioned:

“In some cases, it can be beneficial to have an advocate among consumers who calls for mutual cooperation. This could include a representative from a consumer rights group or organization who can represent their interests and speak out on behalf of all consumers. This individual could help organize collective buying power and coordinate campaigns to push for positive changes in the marketplace. Additionally, they could also provide resources and advice to other consumers about how best to protect their rights when dealing with companies or governments.”

Consumer activists must be prepared to face resistance from consumers. Consumer Activist 3 pointed out:

“It is natural for people to refuse or to ignore your call for good things. Logically, based on our observations, several factors can lead consumers to refuse to cooperate among themselves. These may include a lack of trust or understanding between different groups, conflicting interests, and goals, or the perception that such cooperation is not beneficial or necessary. Additionally, if there is no clear leader who can organize and coordinate efforts, then it may be difficult for consumers to come together in meaningful ways. Finally, if there are economic disparities between different groups of consumers then this could also create an environment where cooperation is unlikely.”

Consumer Activist 3 denied that consumers refused to cooperate with other consumers due to their attitude. Consumer Activist 3 said:

“In my humble opinion, consumers generally have a positive attitude towards mutual cooperation. Mutual cooperation is seen as an effective way to get the most out of a business transaction. Consumers appreciate businesses that are willing to work together and find solutions that benefit both parties. By engaging in collaborative efforts, consumers can feel confident that their needs will be met, while also helping businesses achieve better outcomes for themselves. Additionally, mutual cooperation typically leads to long-term relationships between businesses and customers which further strengthen consumer loyalty and trust. In some cases, consumers may act selfishly if they feel that their interests are not being taken into account or if they believe that other consumers are taking advantage of them. However, this does not mean that all consumers are inherently selfish; many people understand the value of cooperation and will work together to achieve mutual goals.”

Readiness and willingness to cooperate are operated based on taqwa (piety) (Fontaine, 2022; Mhd. Sarif, 2020; Mhd. Sarif et al., 2022b; Tuerwahong & Sulaiman, 2019) and sustainability (Abdul Razak, 2021).

Based on the feedback of the informants, the study found out that more emphasis on al-birr (righteousness) which is inclined towards the sustainable development theories comprised of change theory, ecological modernization theory, sustainable development theory, ecosystem services theory, and resilience thinking theory. Table 2 summarises the feedback of informants with the elements of ta’awun.

In short, the basis for mutual cooperation should be based on informed consent. Consumers can have mutual cooperation among themselves if they have the consent, willingness, and readiness to do so. They may be refused or reluctant, consumer activists must be prepared to face resistance from consumers who may be refused to cooperate with other consumers. The informants argued that empowering responsible consumers through ta’awun (mutual cooperation) for sustainability can be done based on workable and practical mutual cooperation leads to good outcomes. The process is monitored and evaluated with willingness, ability, and piety. Responsible consumerism is intensified with mutual cooperation and the attitude of being socially responsible and sustainable. The taqwa driven ta’awun (mutual cooperation) with responsible consumption sustainability can be done through education and awareness campaigns, providing access to sustainable goods and services, and establishing incentives for businesses to adopt more sustainable practices.

Implications to theory

The study discovered that the empowerment of responsible consumerism with ta’awun (mutual cooperation) emphasizes strongly on al-birr (righteousness) which can be associated with the sustainable development theories. The preceding theories comprise change theory, ecological modernization theory, sustainable development theory, ecosystem services theory, and resilience thinking theory. In addition, the empowerment of responsible consumerism with ta’awun is reinforced by the theories consumerism studies such as social exchange theory, cognitive dissonance theory, and motivation theories.

Implications to practice

In practice, the empowerment of responsible consumerism requires mutual cooperation that is guided by consent, willingness, and readiness of the consumers More advocacy activities should be carried out by the consumer activists to address the reluctance and refusal.

Limitations of this research

This study did not include the opinions of policy makers, public advocates, educators, and community leaders who have close contact with the consumers. In this study, the researchers the informants based on their networking. This method precluded the researchers from approaching possibly more experienced informants.

Future research recommendations

Future studies should include policy makers, public advocates, educators, and community leaders who have close contact with the consumers. The personal interview method employed in this study did not provide an exchange of views as a result of face-to-face discussion that is available in a focus group discussion. The deficiency in using the interview method can certainly be overcome by adopting a focus group discussion with the key stakeholders.

Conclusion

Empowering responsible consumerism can be done through ta’awun (mutual cooperation) that is driven by taqwa (piety), responsibility and sustainability. The roles of ta’awun (mutual cooperation) can be incorporated into routines and activities to advocate, educate, reinforce and sustain responsible consumption for sustainability. The personal interviews with consumer activists argued that the empowering responsible consumers through ta’awun (mutual cooperation) for sustainability can be done based on a workable and practical mutual cooperation leads to good outcomes. The process is monitored and evaluated with the willingness, ability, and piety. A responsible consumerism is intensified with the mutual cooperation and the attitude of socially responsible and sustainable. The taqwa driven ta’awun (mutual cooperation) with responsible consumption sustainability can be done through education and awareness campaigns, providing access to sustainable goods and services, and establishing incentives for businesses to adopt more sustainable practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation for the support of the Department of Business Administration (DEBA), Kulliyyah of Economics and Management Sciences International Islamic University Malaysia, through the Department of Business Administration Research Grant Scheme, DEBA22-013-0019 entitled: “Sejahtera Consumerism” and also the informants, individuals, and supporters of the project.

References

Abdul Razak, D. (2021). The disruptive futures of education—Post-COVID-19 pandemic. In H. van't Land, A. Corcoran, & D. Iancu (Eds.), The promise of higher education. Springer.

Abdul Razak, D., Sanusi, Z. A., Jegatesen, G., & Khelghat-Doost, H. (2013). Alternative University Appraisal (AUA): reconstructing universities’ ranking and rating toward a sustainable future. In S. Caiero, W. Filho, C. Jabbour, & U. Azeiteiro (Eds.), Sustainability assessment tools in higher education institutions: Mapping trends and good practices around the world (pp. 139-154). Springer.

Acquah, A., Nsiah, T. K., Antie, E. N. A., & Otoo, B. (2021). Literature review on theories of motivation. EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review, 9(5), 25-29.

Affolderbach, J. (2022). Translating green economy concepts into practice: ideas pitches as learning tools for sustainability education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 46(1), 43-60. DOI:

Alatas, S. F. (2014). Applying Ibn Khaldūn: The recovery of a lost tradition in sociology. Routledge.

Anderson, C. (2010). Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 74(8), 141. DOI:

Antil, J. H. (1984). Socially Responsible Consumers: Profile and Implications for Public Policy. Journal of Macromarketing, 4(2), 18-39. DOI:

Auda, J. (2008). Maqasid al-shariah: A beginner's guide (Vol. 14). International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT).

Balaji, M. S., Jiang, Y., Bhattacharyya, J., Hewege, C. R., & Azer, J. (2022). An Introduction to Socially Responsible Sustainable Consumption: Issues and Challenges. Socially Responsible Consumption and Marketing in Practice, 3-14. DOI:

Barnett, C., Clarke, N., Cloke, P., & Malpass, A. (2005). The political ethics of consumerism. Consumer Policy Review, 15(2), 45-51.

Blum, S., Buckland, M., Sack, T. L., & Fivenson, D. (2021). Greening the office: Saving resources, saving money, and educating our patients. International Journal of Women's Dermatology, 7(1), 112-116. DOI:

Brieger, S. A., Terjesen, S. A., Hechavarría, D. M., & Welzel, C. (2019). Prosociality in Business: A Human Empowerment Framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(2), 361-380. DOI:

Bugden, D. (2022). Technology, decoupling, and ecological crisis: examining ecological modernization theory through patent data. Environmental Sociology, 8(2), 228-241. DOI:

Burnes, B. (2020). The Origins of Lewin's Three-Step Model of Change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 56(1), 32-59. DOI:

Buttel, F. H. (2000). Ecological modernization as social theory. Geoforum, 31(1), 57-65. DOI:

Carlsen, L., & Bruggemann, R. (2022). The 17 United Nations' sustainable development goals: a status by 2020. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 29(3), 219-229. DOI:

Chandler, D. (2019). Resilience and the end(s) of the politics of adaptation. Resilience, 7(3), 304-313. DOI:

Chapra, M. U., Khan, S., & Al Shaikh-Ali, A. (2008). The Islamic vision of development in the light of maqasid al-Shariah (Vol. 15). International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT).

Chen, J. K. C., & Sriphon, T. (2022). The Relationships among Authentic Leadership, Social Exchange Relationships, and Trust in Organizations during COVID-19 Pandemic. Advances in Decision Sciences, 26(1), 31-68. DOI:

Cooper, J. (2012). Cognitive Dissonance Theory. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Volume 1, 377-397. DOI:

Costanza, R. (2016). Ecosystem services in theory and practice. In M. Potschin, R. Haines-Young, R. Fish & R. K. Turner (Eds.), Routledge handbook of ecosystem services (pp. 15-24). Routledge.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874-900. DOI:

Djasuli, M. (2020). Tauhid and taqwa: The soul in the COSO-ERM framework-An imaginary research dialogue. Journal of Auditing, Finance, and Forensic Accounting, 8(2), 76-84. DOI:

Dorrough, A. R., Froehlich, L., & Eriksson, K. (2022). Cooperation in the cross-national context. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 281-285. DOI:

Dusuki, A. W., & Abdullah, N. I. (2007). Maqasid al-Shari`ah, Maslahah, and Corporate Social Responsibility. American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences, 24(1), 25-45. DOI:

Egberi, A. E. (2020). Motivating employees for performance in the 21st century: A content discuss. The Progress, 1, 14-21.

Ferreira, D. R., & Valdati, J. (2023). Geoparks and Sustainable Development: Systematic Review. Geoheritage, 15(1). DOI:

Flick, U. (2019). From intuition to reflexive construction: Research design and triangulation in grounded theory research. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of current developments in grounded theory (pp. 125-144). Sage Publications.

Fontaine, R. (2022). The life of the Prophet: lessons and relevance for Muslim managers. Journal of Islamic Management Studies, 4(1), 70-83.

Frenken, K. (2017). Sustainability perspectives on the sharing economy. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 1-2. DOI:

Frindte, W., & Frindte, I. (2023). Spaces of meaning, meaningful existence, and cognitive dissonance. In W. Frindte & I. Frindte (Eds.), Support in times of no support: A social psychological search for traces (pp. 175-192). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Galegher, J., Kraut, R. E., & Egido, C. (Eds.). (2014). Intellectual teamwork: Social and technological foundations of cooperative work. Psychology Press.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Harmon-Jones, C. (2003). Whatever happened to cognitive dissonance theory? PsycEXTRA Dataset. DOI:

Harmsen, E. (2008). Islam, Civil Society and Social Work: Muslim Voluntary Welfare Associations in Jordan between Patronage and Empowerment. Amsterdam University Press. DOI: 10.5117/9789053569955

Herrmann, P. (2012). Social empowerment. In L. Maesen & A. Walker (Eds.), Social quality: From theory to indicators (pp. 198-223). Palgrave Macmillan.

Huang, M.-H., & Rust, R. T. (2011). Sustainability and consumption. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 40-54. DOI:

Hussain, S. T., Lei, S., Akram, T., Haider, M. J., Hussain, S. H., & Ali, M. (2018). Kurt Lewin's change model: A critical review of the role of leadership and employee involvement in organizational change. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 3(3), 123-127. DOI:

Jalil, M. A., Islam, M. Z., & Islam, M. A. (2020). Risks and opportunities of globalization: Bangladesh perspective. Journal of Asian and African Social Science and Humanities, 6(4), 13-22.

Kachynska, N., Prakhovnik, N., Zemlyanska, O., Ilchuk, O., & Kovtun, A. (2022). Ecological modernization of enterprises: Environmental risk management. Health Education and Health Promotion, 10(1), 175-182.

Lin, R., Chiang, I.-Y., & Wu, J. (2022). Sustainability|Special Issue: Cultural Industries and Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 15(1), 128. DOI:

Lust, E. M. (2022). Everyday choices: the role of competing authorities and social institutions in politics and development. Cambridge University Press.

Mahyudi, M. (2016). Rethinking the concept of economic man and its relevance to the future of Islamic economics. Intellectual Discourse, 24(1), 111-132.

Mahyudi, M., & Aziz, E. A. (2017). Rethinking the structure of Islamic economics science: The universal man imperative. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 25(2), 227-251.

Malian, I., & Nevin, A. (2002). A Review of Self-Determination Literature: Implications for Practitioners. Remedial and Special Education, 23(2), 68-74. DOI:

Masnavi, M. R., Gharai, F., & Hajibandeh, M. (2019). Exploring urban resilience thinking for its application in urban planning: a review of literature. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 16(1), 567-582. DOI:

McKeown, A., Hai Bui, D., & Glenn, J. (2022). A social theory of resilience: The governance of vulnerability in crisis-era neoliberalism. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 9(1), 112-132. DOI:

McNaughtan, J., Eicke, D., Thacker, R., & Freeman, S. (2022). Trust or Self-Determination: Understanding the Role of Tenured Faculty Empowerment and Job Satisfaction. The Journal of Higher Education, 93(1), 137-161. DOI:

McNeill, D. (2023). Can economics help to understand, and change, consumption behaviour? In A. Hansen, & K. Nielsen (Eds.), Consumption, sustainability and everyday life (pp. 317-337). Palgrave Macmillan.

Mhd. Sarif, S. (2020). Taqwa (piety) approach in sustaining Islamic philanthropy for social businesses. Journal of Islamic Management Studies, 3(1), 58-68.

Mhd. Sarif, S. (2021). Influence Of Taqwa (Piety) On Sustaining Corporate Governance Of Zakat Institutions. AZKA International Journal of Zakat & Social Finance, 149-161. DOI:

Mhd. Sarif, S., & Ismail, Y. (2022). Effect of ta’awun (mutual cooperation) and sejahtera leadership on sustaining community engagement. Online Journal of Islamic Management and Finance (OJIMF), 2(2), 1-21.

Mhd. Sarif, S., Ismail, Y., Yahya, R., & Nabi, A. (2022a). Empowering ta’awun (mutual cooperation) among private school teachers in sustaining sejahtera occupational safety and health environment. Journal of Islamic Management Studies, 4 (2), 26-36.

Mhd. Sarif, S., Ismail, Y., Yahya, R., & Nabi, A. (2022b). Influence of ta’awun (mutual cooperation) and sejahtera leadership in sustaining community engagement. Journal of Islamic Management Studies, 5(2), 3-19. DOI:

Munir, M. (2022). Motivasi organisasi: Penerapan Teori Maslow, McGregor, Frederick, Herzberg dan McLelland (Organisational motivation: Incorporating Theories of Maslow, McGregor, Frederick, Herzberg and McLelland). AL-IFKAR: Jurnal Pengembangan Ilmu KeIslaman, 17(1), 154-168.

Ogryzek, M. (2022). The Sustainable Development Paradigm. Geomatics and Environmental Engineering, 17(1), 5-18. DOI:

Omercic, J., Haneef, M. A. B. M., & Mohammed, M. O. (2020). Economic Thought, Foundational Problems of Mainstream Economics and the Alternative of Islamic Economics. International Journal of Islamic Economics and Finance (IJIEF), 3(2). DOI:

Paterson, M. (2017). Consumption and everyday life. Routledge.

Perkins, D. D., & Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Empowerment theory, research, and application. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 569-579. DOI:

Rakhmat, A. (2022). Islamic Ecotheology: Understanding The Concept Of Khalifah And The Ethical Responsibility Of The Environment. Academic Journal of Islamic Principles and Philosophy, 3(1), 1-24. DOI:

Rieckmann, M. (2017). Education for sustainable development goals: Learning objectives. UNESCO Publishing.

Said, S. N., & Hikmany, A. N. (2016). Zanzibar Government of national unity: A panacea to political or economic stability? Journal of Asian and African Social Science and Humanities, 3, 74-85.

Sassatelli, R. (2007). Consumer culture: History, theory and politics. Sage.

Shabbir, M. S. (2020). Human Prosperity Measurement within The Gloom of Maqasid Al-Shariah. Global Review of Islamic Economics and Business, 7(2), 105. DOI:

Silverman, D. (Ed.). (2020). Qualitative research. Sage Publications.

Sulaiman, R., Toulson, P., Brougham, D., Lempp, F., & Haar, J. (2022). The Role of Religiosity in Ethical Decision-Making: A Study on Islam and the Malaysian Workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 179(1), 297-313. DOI:

Trentmann, F. (2004). Beyond Consumerism: New Historical Perspectives on Consumption. Journal of Contemporary History, 39(3), 373-401. DOI:

Tsen, W. H. (2021). Bank development, stock market development and economic growth in selected Asia economies. Journal of Asian and African Social Science and Humanities, 7(1), 71-85.

Tuerwahong, S., & Sulaiman, M. (2019). Proposing a conceptual framework for the role of taqwa in the career success of Muslim managers in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Management Studies, 2(1), 32-56.

UNDP. (2015). Sustainable Development Goals. UNDP

Venkatesan, M., Yorde Rincon, M., Grevers, K., Welch, S. M., & Cline, E. L. (2022). Socially responsible consumption and marketing in practice. In J. Bhattacharyya (Ed.), Dealing with socially responsible consumers: Studies in marketing (pp. 129-147). Palgrave Macmillan.

Vogt, M., & Weber, C. (2019). Current challenges to the concept of sustainability. Global Sustainability, 2. DOI:

Warde, A. (2015). The Sociology of Consumption: Its Recent Development. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 117-134. DOI:

Webb, D. J., Mohr, L. A., & Harris, K. E. (2008). A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. Journal of Business Research, 61(2), 91-98. DOI:

West, M. A., Tjosvold, D., & Smith, K. G. (Eds.). (2008). International handbook of organizational teamwork and cooperative working. John Wiley & Sons.

Wilkinson, A. (1998). Empowerment: theory and practice. Personnel Review, 27(1), 40-56. DOI:

Yuhertiana, I., Zakaria, M., Suhartini, D., & Sukiswo, H. W. (2022). Cooperative Resilience during the Pandemic: Indonesia and Malaysia Evidence. Sustainability, 14(10), 5839. DOI:

Zainudin, D., Mhd. Sarif, S., Ismail, Y., & Yahya, R. (2021). Humanizing education: edu-action of the prophetic attributes with ta’awun approach. In D. Abdul Razak, et al. (Eds.). Economics and management sciences: Reflections on humanizing education (pp.130-135). Kulliyyah of Economics and Management Sciences IIUM.

Zimmerman, M. A. (2000). Empowerment theory. In J. Rappaport, & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp.43-63). Springer.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 May 2024

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-132-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

133

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1110

Subjects

Marketing, retaining, entrepreneurship, management, digital marketing, social entrepreneurship

Cite this article as:

Sarif, S. M., Ismail, Y., & Zainudin, D. (2024). Empowering Responsible Consumers Through Ta’awun (Mutual Cooperation) for Sustainability. In A. K. Othman, M. K. B. A. Rahman, S. Noranee, N. A. R. Demong, & A. Mat (Eds.), Industry-Academia Linkages for Business Sustainability, vol 133. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 83-101). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2024.05.8