Abstract

The modern working women are facing difficulty to balance their family and job responsibilities. They are burdened with heavy workload both in the office as well as at home. The role conflicts occur when work role demands interfere with the working women's ability to fulfil home-role demands, or home role demands interfere with their work demands. The difficulties were heightened during the lockdown of Covid-19 pandemic, when home is home as well as office. Thus, the role conflict of the working women would escalate their stress levels. They have to resort to relevant coping strategies to overcome or reduce the stress. They also need to have the necessary knowledge, resources, supports and health from office and home for their coping strategies. Hence, this study investigates the relationship of Knowledge, Resources and Support with Coping strategy among the working women towards achieving work and life balance during MCO amidst Covid-19 pandemic. The findings shows that Health, Knowledge, Resources and Support are positively related to Coping at 0.05 level of confidence. These variables postulated to be moderated indicators that explain 47% of variance in Coping. Since the hypotheses are supported, these indicate a substantial model of the study.

Keywords: Health, coping, quality of life balance, working women

Introduction

According to Rubenstein et al. (2020), the demands of work encroaching into home, or vice versa would result in conflict, which have negative outcomes in both. It is crucial for women employees to have a perfect work–life balance, especially those in leadership positions. From the working organisation, these women gain their power and energy for career fulfilment (Schueller-Weidekamm & Kautzky-Willer, 2012). Meanwhile, they also need a well-balanced home (family) life – such as happiness, well-being, harmony, and health. If there is no compatibility between work and family, there would be conflicts between the two and would negatively affect their family and work life. The study by Karabay et al. (2016) indicated that work-home balance influences work-home conflict, which could lead to higher staffs’ turnover. Family is a social institution that could change the biological, psychological, economic, social and legal conditions of an individual’s life and would create conflicts, thus the balance between work and home is imperative. The primary causes of psychological load and stress are inadequate understanding of COVID-19 disease, persistent rumours, social isolation and fear of infection, working in high-risk environments, and contact with sick individuals (Cai et al., 2020). The largest issue facing working professionals is their inability to manage the demands and pressures of both their personal and professional lives (Pluut et al., 2018).

Role interference and role overload are two new problems. Having too much to do and not enough time to do it is known as role overload. When conflicting demands make it difficult or impossible for workers to perform their duties, role interference develops. Work to family interference (WTF), which occurs when work interferes with family life, and family to work interference (FTW), which occurs when work is impacted by family needs, are the two components of role interference (Mohanty & Jena, 2016). Pluut et al. (2018) postulated that it is critical to understand how work interferes with family and find ways to intervene in this work-family process. The need to organise office meetings and online school works are not a mean feat – lead to high encroachment possibility of WTF and FTW (Mohanty & Jena, 2016; Patwardhan, 2014; Pluut et al., 2018). To worsen the situation, the increasing pressure from the office does not abate with MCO. Even before the existence of COVID-19 and the enforcement of MCO, most women employees have to face the work-family conflict (Dettmers, 2017; Kubicek et al., 2015). Numerous studies and reports (Alon et al., 2020; Ascher, 2020; Carlson et al., 2022; Manzo & Minello, 2020; Topping, 2020) highlighted the challenges and difficulties of WLB to the women employees (Uddin, 2021). The need for stay-home and social distancing/physical distancing are difficult for families. The need to buy groceries and food means people have to go out and take the risk of infection. Especially if they are/have family within the vulnerable age groups – 20 to 24 years old and 56 to 59 years old in Malaysia (Povera, 2020), 60 years old and above in USA (Resnick, 2020) and above 65 years old in Europe (Kluge, 2020). According to Roy et al. (2020), people are becoming panic, anxiety and concerned about the global development of COVID-19 infection. Some of them ignore social distancing. According to research by Brooks et al. (2020) and Roy et al. (2020), the experience of isolation and quarantine can worsen symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, rage, and disorientation. Additionally, Banerjee (2020) hypothesises that social isolation, self-quarantine, travel restrictions, and the persistent rumours on social media will have an impact on their mental health.

This study determines the quality of life constructs that would influence the coping strategies of the women employees. It also provides guidelines for the employers in providing necessary assistance to the women employees in order for effective efficient results of work from home. The findings could be the foundation of relevant human resources policies that protect and support the women employees. Uddin (2021) mentioned that there is scant literature about WLB during COVID-19. Although there are numerous studies for non-pandemic perspectives, limited research focused on WLB during COVID-19 pandemic (Lord, 2020).

Literature Review

COVID-19 has exposed greater challenges for working women in juggling their work-family obligations (Anderson & Kelliher, 2020). The Movement Control Order (MCO) means that the working women have to carry the burdens as employee, supervisor, subordinate, committee member, mother, wife, housekeeper from home (Rubenstein et al., 2020; Valizadeh et al., 2018). Prior to MCO, these roles may be less burdening since the roles are separated into two major areas, namely office and home. MCO escalates organisations' reliance on working from home (WFH) method and WFH most frequently results in a higher level of stress (Contreras et al., 2020; Gálvez et al., 2020). According to Irawanto et al. (2021), WFH has a negative effect on employees’ work–life balance due to their inability to adapt to the new working norms as well as dividing the time for work and home. Furthermore, the employees were required to do extra work and extra hours to complete the tasks given to them. This leads to social isolation (disconnected from their working environment) and triggers work stress.

According to Putri and Amran (2021), WFH can either improve the quality of their relationships with their families or blur the boundaries between work and family. This would create difficulty in separating the time for work and family (Crosbie & Moore, 2004; Putri & Amran, 2021). COVID-19 transformed a home into a hybrid area for family, work, school, playground, and entertainment centre. Thus, increasing the role of women employees (Anderson & Kelliher 2020; Uddin, 2021). These pose major challenges in balancing the office responsibilities and family needs, especially if they have younger children. Managing obligations to one's family and career can be challenging. Working women must manage a significant amount of household chores and child care at home (Valizadeh et al., 2018). As a result, individuals encounter work-family problems that lead to high levels of stress in their day-to-day lives, causing them to react to stress by becoming irrationally angry, hesitant, or self-blaming.

Unfortunately, these are the least effective stress management strategies (Valizadeh et al., 2018). Travel restrictions, self-quarantine, social isolation, and the persistently propagating misinformation on social media are additional factors that could have a negative impact on health (Banerjee, 2020; Roy et al., 2020; Shaw et al., 2020). Considerable research has been done on the conflict between work and home responsibilities (Greenhaus & Kossek, 2014; Rubenstein et al., 2020; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012; Williams et al., 2016). When a person's ability to fulfil obligations from their home role is hampered by demands from their job position, conflict results. Similar to this, there can be conflict between the home and the workplace when one's capacity to meet obligations at home is hampered (Rubenstein et al., 2020).

Coping

Varied coping methods are adopted by individuals in response to varied evaluation outcomes, which can result in unequal performance outcomes, as per the Transactional Theory of Stress (TTS) (Zhao et al., 2020). According to TTS, people are more likely to utilise problem-focused coping techniques when they perceive opportunities and gains in the demand. Numerous studies have demonstrated this impact in diverse settings. Pearsall et al. (2009) suggested that in a team setting, when members viewed the problem as a challenge, they would find innovative ways to deal with it.

The findings by Zhao et al. (2020) confirmed three ways of coping strategies – seeking instrumental support, psychological distancing and venting negative emotions. Some studies showed that stress intensity is negatively related to perceived controllability and coping effectiveness was positively related to subjective performance (Laborde et al., 2014). Three types of behaviour – Refusal, Restricted Use, and Mental Disengagement – were postulated as coping behaviours (Jung & Park, 2018).

Nabi (2003) claimed that disappointment leads to proactive coping and anxiety tends to arouse protectiveness. The usual behavioural responses associated with anxiety include escape, avoidance, and protection from the prospective threat (Jung & Park, 2018). Individuals respond to stress in different ways, and the effects of various efficient (problem-oriented) and inefficient (emotion-oriented) coping strategies on people's physical and mental well-being vary (Jameshorani et al., 2022; Sharif & AGHA, 2016). According to Krok and Zarzycka (2020), coping strategies significantly improved workers' mental health; specifically, workers who employed problem-oriented coping strategies during COVID-19 had better psychological outcomes. The problem-oriented coping approach significantly reduced psychological distress and anxiety, including sadness, anxiety, and low self-esteem (Jameshorani et al., 2022; Wang & Wang, 2019).

Knowledge

Knowledge is described by Carnevale and Hatak (2020) as the gathering and storage of data that enables people to stay informed about current events. It is the understanding of safety, the availability of assistance, training opportunities, and self-development in relation to work-life balance. They could find it easier to manage the tension between their jobs in the home and at work with this knowledge (Carnevale & Hatak, 2020). WFH stress could also be lessened through a flexible schedule (Kim et al., 2020). The women employees also needed support (domestic, childcare, and other support services) because without that, their ability to work will be limited, leading to role conflict (Nizam & Kam, 2018).

Resources

The study by Valizadeh et al. (2018), women require support from their families and workplaces. According to Valizadeh et al. (2018), female employees in certain nations have access to community resources for stress management, including recreational facilities, creative arts, self-care promotion, social support, and cognitive skill development.

While physical and cognitive resources help minimise stress from physical workload and cognitive demands, emotional resources lessen the negative impacts of emotional job demands (Bakker et al., 2011). Employees that have supervisor support at work are better equipped to handle client interactions and job expectations by being more efficient. Due to the depletion of personal resources, including time and physical and emotional energy, high job expectations exacerbate work-home conflict (Bakker et al., 2004; Bakker et al., 2011).

Job resources are crucial for all employees, especially women employees to cope with stressful situations (in this context is the balancing of their work life and home life). Some examples of job resources are autonomy, participation in decision making, opportunities for development, quality of the relationship with the supervisor, and performance feedback (Bakker et al., 2011).

Supports

Support is another important factor in decimating the imbalanced WLB. Co-worker and supervisory support (may it be instrumental or emotional) as well as family support would lead to needed balance effectiveness (Uddin et al., 2020; Uddin, 2021). Social support, good relationships and feedback could diminish work overload and emotional demands (Demerouti, 2014; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Mohanty and Jena (2016) revealed women experience more work-home conflict than men do, since the conflict is more prominent on their work lives. Hence, the reduced the women’s ability to manage and balance the demands of work and family life.

Workplace culture and support are important for women employees to reduce their work-life tension (Eaton, 2003; Mohanty & Jena, 2016). Other kinds of support include funded childcare, healthcare and counselling. Women employees also need a supportive partner/spouse to lessen the work-life conflict, especially women in developing nations (Mohanty & Jena, 2016). Support by the partner leads to more productive average work hours than those without this help. According to Carnevale and Hatak (2020) the effect of supportive family role models is positive. The arrangements between supportive family role models and supportive workplace arrangements would decimate the WLB conflict. The women employees also require support for their roles at home. The home responsibilities must be divided accordingly with their partners/spouses.

In most cases, the women take more load and make the most decisions about childcare, children activities and their health management. Although this mostly be the women's preferences, they need to learn to outsource and simplify their responsibilities at home (grocery shopping online with delivery, meal preparation to reduce the stress and work-home conflict. Rosenthal et al. (2020) indicated that the biggest challenge of balancing work-home life is equalising division of labour among partners. Most women physicians carry the main responsibilities of their families. Being a wife and a mother, it is not easy saying no to the family demands and they neglect taking care of themselves (such as getting enough sleep, having down time, or making time to exercise and manage their health).

Health

According to Jha (2020) a healthy body keeps a healthy mind and a healthy mind is crucial to keep an individual's body healthy. The World Federation of Mental Health (Wig, 1997) explained the concept of mental health as being comfortable with self, being comfortable with others and ability to meet life demands. An individual may not be mentally healthy if she is happy and comfortable with herself but if she makes people around them miserable. Thus, mental health is a balance between an individual’s self-interest and social responsibility.

Meanwhile the ability to meet life demands means a mentally healthy person is constantly striving to improve further self-improvement. Working moms with children under the age of five are susceptible to psychological stress, according to Valizadeh et al. (2018). The author also mentioned how stress exacerbates anxiety and sadness and has a detrimental effect on mental health.

A person's mental health is a crucial component of their overall health and plays a role in both maintaining their physical and social well-being. It keeps balance in every life circumstances, either negative or positive. People with healthy mental health feel peace and adapt better in every situation, thus, have better coping skills (Jha, 2020).

Problem Statement

The largest issue facing working professionals is their inability to strike a balance between the demands and pressures of both work and home (Mohanty & Jena, 2016). This is because of two types of role interference that they must overcome: family to work interference (FTW) which occurs when family demands impact work, and work to family interference (WTF) which occurs when work gets in the way of family life (Mohanty & Jena, 2016; Patwardhan, 2014). Pluut et al. (2018) postulated that it is critical to understand how work interferes with family and find ways to intervene in this work-family process. The need to organise office meetings and online school works are not a mean feat – lead to high encroachment possibility of WTF and FTW (Pluut et al., 2018).

COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown enforcement worsen the work-family conflict that is already haunting most working women (Dettmers, 2017). According to Roy et al. (2020), people are becoming panic, anxiety and concerned about the global development of Covid-19 infection. Some of them ignore social distancing. According to research by Brooks et al. (2020) and Roy et al. (2020), the experience of isolation and quarantine can worsen symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, rage, and disorientation. Banerjee (2020) posits that social alienation, self-quarantine, travel restrictions, and the persistent propagation of misinformation on social media will have an impact on their mental well-being. Thus, this study is to investigate the factors that affect the working women’s coping strategies in facing the challenges in balancing their work and personal life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research Questions

The main objective of this study is to investigate the factors influencing the working women’s coping strategies in balancing their work-life balance during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Two the research questions are derived;

What are the challenges that the working women are facing in balancing their work-life balance during Covid-19 pandemic lockdown?

What are the factors influencing the working women’s coping strategies in balancing their work-life balance during Covid-19 pandemic lockdown?

Purpose of the Study

This study would highlight the working women's predicament about balancing their work life and personal life during the MCO amidst COVID-19 pandemic. The findings will identify the factors affecting their level of stress and present the support deemed necessary to assist them in completing their tasks and responsibilities, for both office and home. The study also will contribute moderately to the pool of knowledge on working women, stress management and work-life balance. This study would assist employers to emphasise the working women and provide necessary assistance to effective WFH outputs. The government agencies may benefit from the findings to identify and introduce relevant human resources policies that protect and support the working women.

Research Methods

This study focused on the challenges that the working women in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Brunei, have to face amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. A quantitative, descriptive design and inferential analysis used the SPSS and SmartPLS statistical tools.

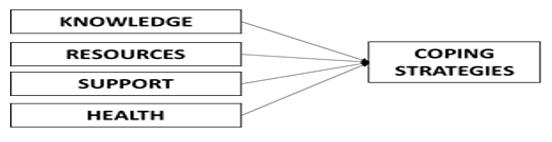

The respondents were working women aged between 25 to 55 years old, in various positions, in selected universities within Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and Indonesia. The online research instrument is more appropriate at the time of data collection and the instrument was developed using Google Form. Figure 1 depicts the research framework of the study.

Findings

501 respondents participated in this study and the majority is aged between 25 and 55 years old (82.6%). About 9% are above 55 years of age and 8.4% are below 25 years old. 41.1% are undergraduate degree holders and 25% with postgraduate degrees. About 57% of the respondents are earning between RM5001 and RM10,000 monthly. 23.6% earns below RM5,000 monthly and only 9.7% are earning a monthly income above RM10,000. They are made up of academicians (42.7%), administration staff (25.3%) and technical staff (18.6%), support and general staff (13.4%).

Majority are married (56.1%) and divorced or widowed (23.2%). About 19% are single. Most of the respondents have between 2 to 5 children (44.9%), whilst about 20% either have more than 5 children or none respectively. Table 1 summarises the respondents’ demographic details. More than 70% are students undertaking undergraduate degree programs, whilst only 13.8% are pursuing their postgraduate degree. About 49% are active students within the participating HLIs, 19% are the academicians, 20.5% are the staff within the administrative and support divisions and 10% are among the management of the HLIs.

The next common measure for internal consistency of the data is Composite Reliability (CR) which must be greater than 0.708 (for each construct) to achieve satisfied internal consistency (Hair et al., 2021). The CR value results in Table 2 demonstrated internal consistency reliability among the constructs.

The findings in Table 2 show that all loading, AVE, and CR values exceeded the threshold values. The loading values were between 0.872 and 0.942 (above 0.8), and the AVE values were between 0.674 and 0.829 (exceeded 0.5 threshold). Meanwhile, the CR values ranged between 0.922 and 0.951 – above the threshold of 0.7. These results confirmed the convergent validity. It also indicates a good internal consistency of the measurement model for the constructs.

Fornell and Larcker (1981) Criterion measures the discriminant validity by comparing the square root of each construct’ average variance extracted with its correlation (Hair et al., 2018). The discriminant validity occurs when the square root of AVE is larger than the highest correlation. Since all the correlations values of this study are less than square roots AVE, the discriminant validity is established (Franke & Sarstedt, 2019) and verified (Henseler et al., 2015; Ramayah et al., 2018). Thus, the results of the convergent validity and the discriminant validity tests of the items created for this study were valid and reliable.

HTMT (Table 4) is an alternative to evaluate discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2021). The results in Table 3 show that all values are lower than the required HTMT criterion of 0.85 (Kline, 2011) and 0.90 (Gold et al., 2001). Thus, the discriminant validity is ascertained. Furthermore, the confidence level does not show any value of 1 among the constructs (Henseler et al., 2015). This also confirmed the discriminant validity of the study. The outcome also shows that Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values are less than 5 as per suggested by Sarstedt et al. (2022) and Ramayah et al. (2018). Thus, there are no collinearity problems for all the indicators in Coping, Health, Knowledge, Resources and Support.

From Table 5, the R2 results show that Health, Knowledge, Resources and Support are moderate indicators for Coping. The predictors – Health, Knowledge, Resources and Support – explain 47% of variance in Coping. All the hypotheses are supported because there is no “0” straddled in between the confidence intervals and bias results. Conclusively H1, H2, H3 and H4 have small effects as indicated by the values of Q2 of 0.034. Thus, the results indicate a substantial model of the study.

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that the women employees need to be equipped with relevant knowledge in managing the stressful challenges in balancing their work life and personal life. This study confirmed the relationship of Knowledge, Resources, Support and Health with Coping strategy among the working women in order to achieve work and life balance during MCO amidst Covid-19 pandemic. The adequate knowledge about managing stress and work related information influence their coping capability. The availability of support from office and home are critically needed in order to be effective both at work and at home.

This study also postulated that support from office and home is one of the biggest challenges but has a positive effect towards coping (concurrent with findings by Carnevale & Hatak, 2020; Rosenthal et al., 2020; Uddin et al., 2020; Uddin, 2021). The resources provided by the employers are also crucial for these working women to perform effectively and efficiently. The findings of this study support previous research (such as Carnevale & Hatak 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Nizam & Kam, 2018). Meanwhile Health – both Physical and Emotional – affected by coping styles of the working women. This is similar to the findings by Jameshorani et al. (2022), Krok and Zarzycka (2020), Wang and Wang (2019) and Sharif and AGHA (2016).

The findings identified that Knowledge, Resources Support and Health affecting the working women's level of stress and their coping ability in performing their work and home tasks and responsibilities. This study contributes moderately to the pool of knowledge on working women, stress management and work-life balance. This study offers some guidance to employers in assisting the working women towards more effective WFH outputs. Although the lockdown was the chaotic period for everybody, there are also positive outcomes created such as better family bonding (Roshgadol, 2020) and enhanced marital ties (Alhas, 2020).

The study cannot be generalised because of several limitations. The respondents are among the faculty and staff of selected universities in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Brunei. There are more Malaysians than the other countries due to MCO travel restrictions, thus the number of respondents among the countries were not equivalent in numbers. For the future, studies should focus on working women from other industries and countries. Furthermore, the variables were chosen based on the relevancy of the study. Other factors could be introduced into the model such as education level and social class.

Acknowledgments

Heartiest gratitude to Universiti Tenaga Nasional for funding this study under BOLD 2021 Research Grant.

References

Alhas, A. (2020). More family time amidst coronavirus isolation at home. Anadolu Agency. Retrieved on April 21st, 2023, from, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/lateston-coronavirus-outbreak/morefamily-time-amid-corona virusisolation-at-home/1812529

Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). This Time It's Different: The Role of Women's Employment in a Pandemic Recession. DOI:

Anderson, D., & Kelliher, C. (2020). Enforced remote working and the work-life interface during lockdown. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 35(7/8), 677-683. DOI:

Ascher, D. (2020, May 27). Coronavirus: Mums do most childcare and chores in lockdown. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52808930?fbclid=IwAR1pbW4amJI45txjsL2rjIhiiVnhSfx0nWGvHG6qoBgR2tu0P6SuCk9Zg7Q

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43(1), 83-104. DOI:

Bakker, A. B., ten Brummelhuis, L. L., Prins, J. T., & der Heijden, F. M. M. A. v. (2011). Applying the job demands-resources model to the work-home interface: A study among medical residents and their partners. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 170-180. DOI:

Banerjee, D. (2020). The COVID-19 outbreak: Crucial role the psychiatrists can play. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 50, 102014. DOI:

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912-920. DOI:

Cai, Z., Zheng, S., Huang, Y., Zhang, X., Qiu, Z., Huang, A., & Wu, K. (2020). Emotional and Cognitive Responses and Behavioral Coping of Chinese Medical Workers and General Population during the Pandemic of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6198. DOI:

Carlson, D. L., Petts, R. J., & Pepin, J. R. (2022). Changes in US Parents' Domestic Labor during the Early Days of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sociological Inquiry, 92(3), 1217-1244. DOI:

Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183-187. DOI:

Contreras, F., Baykal, E., & Abid, G. (2020). E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and Beyond: What We Know and Where Do We Go. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. DOI:

Crosbie, T., & Moore, J. (2004). Work-life Balance and Working from Home. Social Policy and Society, 3(3), 223-233. DOI:

Demerouti, E. (2014). Individual strategies to prevent burnout. In M. P. Leiter, A. B. Bakker, & C. Maslach (Eds.), Burnout at work: A psychological perspective (pp. 32–55). Psychology Press.

Dettmers, J. (2017). How extended work availability affects well-being: The mediating roles of psychological detachment and work-family-conflict. Work & Stress, 31(1), 24-41. DOI:

Eaton, S. C. (2003). If You Can Use Them: Flexibility Policies, Organizational Commitment, and Perceived Performance. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 42(2), 145-167. DOI:

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. DOI:

Franke, G., & Sarstedt, M. (2019). Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: a comparison of four procedures. Internet Research, 29(3), 430-447. DOI:

Gálvez, A., Tirado, F., & Martínez, M. J. (2020). Work-Life Balance, Organizations and Social Sustainability: Analyzing Female Telework in Spain. Sustainability, 12(9), 3567. DOI:

Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185-214. DOI: 10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

Greenhaus, J. H., & Kossek, E. E. (2014). The Contemporary Career: A Work-Home Perspective. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 361-388. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091324

Hair, J. F., Astrachan, C. B., Moisescu, O. I., Radomir, L., Sarstedt, M., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2021). Executing and interpreting applications of PLS-SEM: Updates for family business researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 12(3), 100392. DOI:

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2018). Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equations Modelling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135. DOI:

Irawanto, D., Novianti, K., & Roz, K. (2021). Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work-Life Balance and Work Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia. Economies, 9(3), 96. DOI:

Jameshorani, S., Kakabaraei, K., Afsharinia, K., & Hossaini, S. (2022). Relationship between Coping Styles and Blood Pressure in the Staff of Covid-19 Wards of Hospitals of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences During 2020 - 2021. Journal of Clinical Research in Paramedical Sciences, 11(1). DOI:

Jha, N. K. (2020). Ways of Coping and Mental Health among Male and Female Police Constables: A Comparative Study. The Indian Police Journal, 159.

Jung, Y., & Park, J. (2018). An investigation of relationships among privacy concerns, affective responses, and coping behaviors in location-based services. International Journal of Information Management, 43, 15-24. DOI:

Karabay, M. E., Akyüz, B., & Elçi, M. (2016). Effects of Family-Work Conflict, Locus of Control, Self Confidence and Extraversion Personality on Employee Work Stress. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 269-280. DOI:

Kim, J., Henly, J. R., Golden, L. M., & Lambert, S. J. (2020). Workplace Flexibility and Worker Well-Being by Gender. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(3), 892-910. DOI:

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. Guilford Press.

Kluge, H. (2020). A new vision for WHO's European Region: united action for better health. The Lancet Public Health, 5(3), e133-e134. DOI:

Krok, D., & Zarzycka, B. (2020). Risk Perception of COVID-19, Meaning-Based Resources and Psychological Well-Being amongst Healthcare Personnel: The Mediating Role of Coping. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(10), 3225. DOI:

Kubicek, B., Paškvan, M., & Korunka, C. (2015). Development and validation of an instrument for assessing job demands arising from accelerated change: The intensification of job demands scale (IDS). European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 898-913. DOI:

Laborde, S., Dosseville, F., & Kinrade, N. P. (2014). Decision-specific reinvestment scale: An exploration of its construct validity, and association with stress and coping appraisals. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15(3), 238-246. DOI:

Lord, P. (2020). The social perils and promise of remote work. Journal of Behavioral Economics for Policy, 63-67.

Manzo, L. K. C., & Minello, A. (2020). Mothers, childcare duties, and remote working under COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: Cultivating communities of care. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(2), 120-123. DOI:

Mohanty, A., & Jena, L. K. (2016). Work-Life Balance Challenges for Indian Employees: Socio-Cultural Implications and Strategies. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 04(01), 15-21. DOI:

Nabi, R. (2003). Exploring the framing effects of emotion: Do discrete emotions differentially influence information accessibility, information seeking, and policy preference? Communication Research, 30(2), 224–247.

Nizam, İ., & Kam, C. (2018). The determinants of work-life balance in the event industry of Malaysia. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics, 5(3), 141-168.

Patwardhan, N. C. (2014). Work-Life Balance Initiations for Women Employees in the IT Industry. Work-life Balance: A Global Perspective. Wisdom Publications.

Pearsall, M. J., Ellis, A. P. J., & Stein, J. H. (2009). Coping with challenge and hindrance stressors in teams: Behavioral, cognitive, and affective outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(1), 18-28. DOI:

Pluut, H., Ilies, R., Curşeu, P. L., & Liu, Y. (2018). Social support at work and at home: Dual-buffering effects in the work-family conflict process. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 146, 1-13. DOI:

Povera, A. (2020). RM25 million set aside for vulnerable groups. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/03/578706/rm25-million-set-asidevulnerable-groups

Putri, A., & Amran, A. (2021). Employees' Work-Life Balance Reviewed From Work From Home Aspect During COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Management Science and Information Technology, 1(1), 30. DOI:

Ramayah, T. J. F. H., Cheah, J., Chuah, F., Ting, H., & Memon, M. A. (2018). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using smartPLS 3.0. An updated guide and practical guide to statistical analysis, 978-967.

Resnick, B. (2020). What Have We Learned About Nursing From the Coronavirus Pandemic? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(7), 997-998. DOI:

Rosenthal, J., Wanat, K. A., & Samimi, S. (2020). Striving for balance: A review of female dermatologists' perspective on managing a dual-career household. International Journal of Women's Dermatology, 6(1), 43-45. DOI:

Roshgadol, J. (2020). Quarantine quality time: 4 in 5 parents say coronavirus lockdown has brought families closer together. Study Finds, 21.

Roy, D., Tripathy, S., Kar, S. K., Sharma, N., Verma, S. K., & Kaushal, V. (2020). Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102083. DOI:

Rubenstein, A. L., Peltokorpi, V., & Allen, D. G. (2020). Work-home and home-work conflict and voluntary turnover: A conservation of resources explanation for contrasting moderation effects of on- and off-the-job embeddedness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103413. DOI:

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Pick, M., Liengaard, B. D., Radomir, L., & Ringle, C. M. (2022). Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychology & Marketing, 39(5), 1035-1064. DOI:

Schueller-Weidekamm, C., & Kautzky-Willer, A. (2012). Challenges of Work-Life Balance for Women Physicians/Mothers Working in Leadership Positions. Gender Medicine, 9(4), 244-250. DOI: 10.1016/j.genm.2012.04.002

Sharif, N., & AGHA, Y. A. (2016). Relation between coping ways with stress and systolic and diastolic blood pressure in coronary heart disease.

Shaw, W. S., Main, C. J., Findley, P. A., Collie, A., Kristman, V. L., & Gross, D. P. (2020). Opening the Workplace after COVID-19: What Lessons Can be Learned from Return-to-Work Research? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 30(3), 299-302. DOI:

Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work-home interface: The work-home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545-556. DOI:

Topping, A. (2020, May 27). Working mothers interrupted more often than fathers in lockdown—Study. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/27/working-mothers-interrupted-more-often-than-fathers-in-lockdown-study

Uddin, M. (2021). Addressing work-life balance challenges of working women during COVID-19 in Bangladesh. International Social Science Journal, 71(239-240), 7-20. DOI:

Uddin, M., Ali, K., & Khan, M. A. (2020). Impact of perceived family support, workplace support, and work-life balance policies on work-life balance among female bankers in Bangladesh. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 28(1), 97–122

Valizadeh, S., Hosseinzadeh, M., Mohammadi, E., Hassankhani, H., Fooladi, M. M., & Cummins, A. (2018). Coping mechanism against high levels of daily stress by working breastfeeding mothers in Iran. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 5(1), 39-44. DOI:

Wang, Y., & Wang, P. (2019). Perceived stress and psychological distress among chinese physicians: The mediating role of coping style. Medicine, 98(23), e15950. DOI: 10.1097/md.0000000000015950

Wig, N. N. (1997). Stigma against mental illness. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 39(3), 187=189.

Williams, J. C., Berdahl, J. L., & Vandello, J. A. (2016). Beyond Work-Life "Integration". Annual Review of Psychology, 67(1), 515-539. DOI:

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121-141. DOI: 10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121

Zhao, X., Xia, Q., & Huang, W. (2020). Impact of technostress on productivity from the theoretical perspective of appraisal and coping processes. Information & Management, 57(8), 103265. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 May 2024

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-132-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

133

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1110

Subjects

Marketing, retaining, entrepreneurship, management, digital marketing, social entrepreneurship

Cite this article as:

Sabri, S. S., Said, M., & Asshidin, N. H. N. (2024). Coping Ability Influencing Factors for Working Women Quality Life Balance. In A. K. Othman, M. K. B. A. Rahman, S. Noranee, N. A. R. Demong, & A. Mat (Eds.), Industry-Academia Linkages for Business Sustainability, vol 133. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 859-872). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2024.05.70