Abstract

This article aims to explain the importance of gender in work-family conflict and job satisfaction. Work-family conflict may be impacted by job demands and stress. The conflict between work and family can put a strain on employees internally. Research on work and family conflict began several decades ago, but due to the rise in the number of dual-earning families, it is now more pertinent than ever. The primary goal of this study is to determine the influence of gender on work-family conflict and job satisfaction. The research design for this study involved the quantitative method of convenience sampling and survey questionnaires that were developed based on a thorough and detailed analysis of the relevant literature. The researcher established the significance of gender and its functions in work-family conflict based on the study. Gender has also been found to have an impact on job satisfaction. The study's findings highlight the gender variations in work-family conflict. The distinctive role of gender and its significance in work-family conflict are identified by this study. The study also focuses on the job satisfaction of genders based on the work-family conflict they faced. The implications of this study were discussed.

Keywords: Balance, gender, satisfaction, work-family conflict, work-family work stress

Introduction

In recent years, various terms such as "work-life balance," "work-home interference," "work-family integration," "work-family conflict," "work-family enrichment," and "work-family spillover" have been intensively discussed by academics, politicians, and the public (Carlson et al., 2006; Feierabend et al., 2011; Van Ruysseveldt et al., 2011). The phenomena of work-family conflict, a type of inter-role conflict brought on by somewhat mismatched job and family responsibilities, has received more attention in recent years (Miller et al., 2022).

Balancing work and family responsibilities has received a lot of scholarly attention in recent years. Work and family (non-work) play an important role in most people's adult lives, and both domains are regarded as the backbone of human existence (Md‐Sidin et al., 2010). According to Fagan and Burchell (2002), globalisation, downsizing, and flexible work patterns have resulted in an increase in job demands and pressure, as well as a daily battle to balance work and family commitments. Studies on work-family conflict and its effects have been more relevant in recent years, and it appears that this importance will only increase in the future (Kao et al., 2020).

Byron (2005) stated that the increase in dual-career couples and single-parent households and the decrease in traditional, single-earner families mean that responsibilities for work, housework, and childcare are no longer confined to traditional gender roles. In addition, managing work-family responsibilities is more difficult and challenging in households with a more conventional "husband works, wife stays at home" family unit (Boles et al., 2001; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Gill and Davidson (2001) support this statement by saying that men have taken on greater family duties, partly as a result of rising divorce rates that lead to a rise in single parenting. Because of this, most men are starting to feel more stressed out and at odds with one another as they balance their roles as parents and workers (Tennant & Sperry, 2003).

To fulfil this, employees need to find themselves struggling to balance the demands of work and the demands of family. The excessive pressure and scarcity of free time may also adversely affect their ability to deal with their responsibilities. Strong family support at work is associated with lower levels of work-family conflict among employees (Lapierre et al., 2008), which will decrease the levels of job stress and reduce turnover (Bozo et al., 2009). In contrast, high levels of work-family conflict among employees will lead to high levels of job stress and higher turnover rates (Kreiner, 2006).

Generally, work and personal life interface situations have been studied from the perspective of the problems individuals face when trying to find a balance between their work and family lives. For example, individuals have difficulty with time pressures arising due to work and family. Furthermore, strain within either life negatively affects one's work-life experiences. Thus, excessive working hours, workplace stress, and personal obligations can lead to conflicts between work and home life and impair performance or role behaviours in the other domain, according to Greenhaus and Beutell (1985), Carlson (2002).

Therefore, everyone who has a working life must find brilliant ways to combine, balance, and well manage their time to accurately fulfil the demands of their working and private lives. As a person's working life affects their personal life, the reverse can also be true. Based on Eby et al. (2005), both favourable and unfavourable outcomes could result. Guest (2002) and Sturges and Guest (2004) have suggested that the researcher should not limit their attention to work and family-related problems but should also give substantial consideration to other non-work domain issues, such as hobbies and other leisure activities.

Work-family issues are becoming more common and significant, which is consistent with changes in family arrangements and the nature of work (Watson et al., 2003). The rise in women's employment, the number of part-timers and casual workers, the amount of time spent working rather than at home, and recent modifications to industrial relations laws that alter the nature of work are other factors that impact work-family conflict (Baird et al., 2006).

In previous research, as stated by Anderson (2002), Babin and Boles (1996), and Frye and Breaugh (2004), most studies have found a negative relationship between these two variables: work-family conflict (WFC) and job satisfaction. This is also supported by Choi et al. (2013), who found that work-to-family conflict negatively affected job satisfaction. All the current correctional research, with the exception of Lambert et al. (2002) study, indicates a connection between work-family conflict and job satisfaction. A moderating role for gender between work-family conflict and distinct repercussions, however, was not found by any of the meta-analyses that were conducted (Nohe et al., 2015). Using a different perspective to investigate the role of gender and looking at potential mediating factors can produce more fruitful findings and help shed light on work-family conflicts and their repercussions.

Work and family are the two most important roles in a person's life, and it is not surprising that they can cause conflict if combined. Mostly, each individual experiences work and family life (Karatepe, 2010; Netemeyer et al., 2005). According to Boyar et al. (2008) and Kim et al. (2005), it is strongly stated that work-family conflict is influenced by long working hours, duty, and heavy workloads. Brough and O'Driscoll (2005) provided support for this viewpoint, indicating that "a person's capacity to dedicate time and energy to their family life will be reduced if they have to work long hours and face significant job demands" (p. 224). Conversely, individuals won't have as much time to spend with their families. To effectively meet multiple demands in both domains and to conveniently obtain and utilise the necessary resources, it is imperative to achieve a successful balance between the work and family spheres (Grzywacz & Bass, 2003).

According to research, there are two different but related types of role conflict: work-interfering with family (WIF) and family-interfering with work (FIW). Conflict resulting from work obligations interfering with family obligations is known as work interfering with family (WIF). The stress that results when work and family obligations collide is known as family interfering with work (FIW). Both are essentially the outcome of a person's endeavour to satisfy the expectations of the family, work, and home environments in which they are involved. Family interfering with work is the term used to describe the strain that arises when job and family responsibilities interconnect (FIW). Both are the result of an individual's attempt to meet the demands of their home, workplace, and family settings. Role performance in another domain becomes more challenging due to demands from one domain. Individual who experiences higher WFC experiences work in greater number of hours and face greater demands at work, however, work autonomy may lower one's WIF (Allen et al., 2020).

It is supported by Greenhaus and Powell (2003) that work-family conflict occurs when work interferes with competing family activities or when work stress negatively affects behaviour within the family domain. Due to the time, effort, and dedication required for each of these roles—such as worker, husband, and, in many cases, parent—work-family conflict (WFC) arises when an individual must fulfil numerous responsibilities. Overload and interference are the two forms of strain that arise from the combined demands of these roles (Duxbury & Higgins, 1991). When there is too much demand on a person to fulfil several roles effectively, overload results. Interference also arises when competing demands make it impossible to fulfil the criteria of several roles at once.

According to Jain and Nair (2021), contentment is an attitude that stems from a person's unique evaluation of their employment, implying that contentment is more than just sentiments and also represents how one views and evaluates their work. Mugunthan (2013) defined job satisfaction as an employee's attitudes toward their position, the workplace, their compensation, benefits, and other factors. Furthermore, the social sciences believe that an individual's ability to realise their wants, aspirations, values, and beliefs is a necessary condition for overall fulfilment, including job satisfaction (Kuo et al., 2018).

The degree of employee satisfaction with the work environment will mostly determine the achievement of organisational goals and targets (Kaur, 2012). In contrast, an employee who is dissatisfied with his work will feel negatively about it and a satisfied employee will feel positive about his employment (Khalid et al., 2011). According to Abbas et al. (2013), a satisfied employee consistently demonstrates their ability to perform well, but a dissatisfied employee will causes the organisation to lose. All in all, the internal feeling of fulfilment or dissatisfaction regarding one's work is the main emphasis of job satisfaction (Thompson & Phua, 2012). High levels of job satisfaction are produced by favourable experiences such as amiable coworkers, generous pay, understanding managers, and appealing employment (Giannikis & Mihail, 2011). Yee et al. (2010) highlighted out that a person's level of job satisfaction improves with how well their work environment matches their needs, values, or personal traits.

One type of work-family conflict is time-based conflict, or time strain. The higher the work hours and job demands, the more stress and negative effect it has on one's perception of work (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010). For example, Booth and van Ours (2007) found that the level of satisfaction for part-time working women was higher for full-time employed women. It demonstrated that work hours are a highly relevant antecedent of work satisfaction. Satisfied workers will subsequently devote more time to their jobs, engage in work-related activities more passionately, constructively, and successfully, and experience lower employee turnover (Agarwal et al., 2001). As such, organisations need to strive to enhance the levels of job satisfaction among their employees, as this has a positive stimulus effect on the organization's prosperity (Wongsuwan et al., 2023).

A significant factor is gender socialisation, which both directly and indirectly impacts behaviour and helps decide how much men and women internalise traditional conceptions of gender differences (Barnett & Rivers, 2004). Inconsistent findings have been found in several research on how gender differs in juggling work and home obligations (Hill et al., 2010). The desire to pursue careers in traditionally male fields like law and medicine has eliminated gender disparities in this regard (Sax, 2005).

The ways that men and women experience work-family issues varied according to their gender roles (Frone et al., 1992; Gutek et al., 1991). Previous studies have also shown that women are far more likely than men to be involved in work-family disputes (Lundberg, 1996). However, Byron (2005) painted a different image in his meta-analysis of over 60 research. Men and women suffer work-family conflict (WFC) to varying degrees, according to Byron (2005). Contrarily, family-work conflict (FWC) affects women more frequently than it does males. However, compared to working mothers, working fathers reported lower levels of family-work conflict (Hill et al., 2003).

Furthermore, Hochschild and Machung (1989) noted that women appear to be more responsible for adjusting to the demands of both work and family in dual-earner households. There is proof that married women still have to do more childcare and housework than their male spouses (Wiersma, 1994). Furthermore, the researcher asserted that women experience more work-family conflict than males do, citing Cinamon and Rich (2002) as support.

Kinnunen and Mauno (1998), however, provided evidence to the contrary. It was established that in Finland, there is no gender difference in the amounts of family-to-work and work-to-family interference in a sample of working men and women. According to Beutell (2010), who drew support from a recent study, working fathers and moms had similar levels of work-family conflict.

Methodology and Finding

In order to analyse WFC between genders, the statistical population involved 105 employees around the Shah Alam area. Based on the objectives of the study, the sampling size is based on the volunteers of those respondents who were willing to answer the questionnaire and those participants who met some criteria for the study.

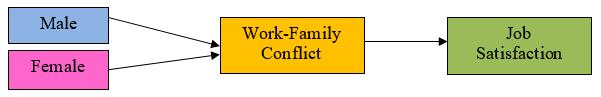

This study's primary goal was to examine the gender-to-WFC model link empirically. The work was influenced by the most integrated model to date, as well as the model presented by Frone et al., 1997. Research indicates that distinct work-family conflict models may be utilised or that certain models may operate differently for men and women. Nevertheless, the majority of research restricts its scope to confirming the existence of gender differences, and very few have concentrated on examining these models (Parasuraman & Greenhaus, 2002). Gender differences should be taken into account when analysing work-family conflict because work and family have historically been associated with specific responsibilities (McElwain et al., 2005). Based on this, a conceptual model was developed to guide the present research (Figure 1). This model was tested in the current study.

Among the 105 respondents, the majority were female, making up 60.0% (n = 63), closely followed by 40.0% (n = 42) of the respondents being male. Regarding equality of variance, since there is no significant difference between gender groups, p =.23, which is more than 0.05, In this condition, we can’t reject the null hypothesis. It means that the variance of two groups in the work-family conflict is equal. Although the mean value of males is slightly higher than females, there is no difference between males and females regarding work-family conflict. Therefore, hypotheses H1a and H1b are rejected.

Regarding equality of variance, since there is no significant difference between gender groups (p =.976), which is more than 0.05, In this condition, we can’t reject the null hypothesis. It means that the variances of two groups for job satisfaction are equal. Although the mean value of males is slightly higher than females, there is no difference between males and females regarding job satisfaction, as this difference is not significant. Therefore, hypothesis H2 is rejected.

Overall, there is a significant positive relationship between independent and dependent variables (r = 0.383, p = 0.00 < 0.05). In the multiple regression analysis (model summary, table 11), the result found that work-family conflict explained 14% (adjusted R square) of the variance associated with job satisfaction. The analysis also showed a significant relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction, as indicated by the ANOVA result (table 12) and the F value (F = 17.72, P = 0.00 < 0.05). Additionally, the coefficients result (table 1) showed a significant correlation between work-family conflict and job satisfaction (P = 0.00 < 0.05, beta value -.383). Based on the research results, the null hypothesis H3 is rejected.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study emphasises the role of gender in the relationship between work and family conflict. The researcher found that the majority of respondents in the study were female (60.0%). Most of the respondents were aged between 25 and 35 years old (54.3%), and most of them were already married (61.9%). In terms of children taken care of, single respondents placed second highest. So they don't have children yet. The highest group in occupation status is permanent (52.4%), while most of the respondents hold diploma qualifications (38.0%).

For research question 1, the researcher found that there is no significant difference between the gender groups as p =.23, which is more than 0.05. Although the mean value of males is slightly higher than females, there is no difference between males and females regarding work-family conflict. Therefore, hypotheses H1a (males facing work-family conflict more than females) and H1b (females facing work-family conflict more than males) are rejected.

Frone (2003) provided support for the above thesis by summarising the lack of significant variations in work-family and family-work conflict levels in various sample instances. Research on the gender disparities in work-family conflict, however, has yielded wildly inconsistent results, and vice versa (Voydanoff, 2002). Men are more likely than women to face work-family conflict, according to certain studies (Duxbury & Higgins, 1991). Work-family conflict affects women more than it does males (Carlson, 2002). Men are more likely than women to face work-family conflict, according to certain studies (Duxbury & Higgins, 1991). Work-family conflict affects women more than it does males (Carlson, 2002). According to Pleck (1977), due of their gender identity (self-concept), men and women are more likely to encounter interference from work to family and from work to family, respectively, and because of this, women are more likely to experience interference from work to family. Research by Ahmad (1996) on eighty-six female researchers and Ahmad (2008) on one hundred professional women revealed that work-family conflict affects married working women in Malaysia. Research by Ahmad (1996) on eighty-six female researchers and Ahmad (2008) on one hundred professional women revealed that work-family conflict affects married working women in Malaysia.

In addition, for the second question, the result found that there is no significant difference between men and women in job satisfaction, as the P value is 0.976, which is more than 0.05. Although the mean for men is higher than for women, there is no difference between men and women regarding job satisfaction. This result is supported by Al-Ajmi (2006), who conducted a study in Kuwait and found that there is no significant difference between genders in job satisfaction as both have the same satisfaction with the job. However, this result is contrary to the other researchers’ study. According to Voydanoff (1980), there are a few differences in the appraisal of job and family characteristics by men and women, while Randy Hodson (1989) and Centers and Bugental (1966) stated that women receive higher job satisfaction than men as women are more interested in different aspects of work than men were.

Based on the third question, there is a significant relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction (r = 0.383, p = 0.00 0.05). From the ANOVA result, the analysis showed a significant relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction (F = 17.72, P = 0.00 0.05). Additionally, the coefficient result also showed a significant correlation between work-family conflict and job satisfaction (P = 0.00 0.05), and the beta value is -0.383. Based on the research result, hypothesis 3, which is that there is a negative relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction, is rejected.

Many researchers have demonstrated a significant negative correlation between work-family conflict and job satisfaction. For example, Ahmad and Omar (2010) stated that among single-mother employees in Malaysia, work-family conflict was negatively associated with job satisfaction. Judge et al. (1994) study on male executives shows that an increase in work-family conflict can lead to reduced job satisfaction.

Treat Employees as Important Assets

Woodruffe (2006) stated that most organisations rarely miss an opportunity to remind their audiences and themselves that their people and surroundings are their most precious assets. Through the study, he also mentioned that organisations should treat every member of their staff as an individual. He further added that employees like to feel that there is someone available to whom they can turn for advice if they need it. This is supported by the open-ended questions. In this study, the majority of respondents stated that their employers are not aware of their needs and wants, and this result will make the respondents not satisfied with their job, stressed, and decide to leave.

From the researcher’s review, the employees must be treated with respect and mostly respected. Paying them fairly and affording them opportunities for career advancement gives them motivation by encouraging their hidden, best potential skills for development. Other than that, the organisation should treat their employees fairly and without biases, which can create dissatisfaction towards other employees.

Understanding work-family conflict requires considering gender issues. Gender roles influence how men and women function in society, including at home and in the workplace (Eagly & Wood, 2012). A meta-analysis carried out by Shockley et al. (2017) demonstrates that there is no difference in the concerns about conflict between work and family expressed by men and women. Lyu and Fan (2022) found no significant differences between men and women on the issue of work-family conflict.

Provide Social Support

In order to understand workplace conflict and issues employees have with balancing work and family responsibilities, employers should also demonstrate a high degree of social support for their employees by acting with concern and being open to hearing about their issues. The majority of respondents indicated in response to the open-ended questions that family and financial problems are other factors that can spark conflict. In order to minimise the burden your staff members bear, you as a responsible employer should pay attention to what they have to say, assist them, and provide them with plenty of resources, including cash. In this scenario, the staff members will sense that the company values them.

Individual Sacrifices for Work and Family

It depends on the assumption that people may have many different motivations for attributing a given level of importance or salience to a specific life role. Furthermore, various individuals can demonstrate a certain level of importance in different ways. According to several studies, four different dimensions of sacrifice (i.e., willingness to sacrifice, behavioural sacrifice, satisfaction with sacrifice, and costs of sacrifice) have varying relationships with well-being (Righetti et al., 2020). Individuals' willingness to sacrifice was found to be favourably connected with their well-being as well as their partner's relationship well-being. Personal well-being, on the other hand, was inversely connected with behavioural sacrifice. Individual and couple well-being was positively connected with satisfaction with sacrifice. The cost of sacrifice was negatively associated with one's own and partner's relationship well-being.

Future Research

The findings of the study are needed for future research. There are a few recommendations for future research. Some of the recommendations are:

As for future research, either in the public or private sectors, additional studies in this field should be done on the topics of work-family conflict and family-work conflict in different organisations. In doing so, the study will be able to be used and conducted across a range of industries rather than being limited to a single one. In order to verify the veracity of the results, more research with a bigger sample size is advised. An extensive population should be studied in order to produce more precise results. Knowing the impact of work-family and family-work conflict on employees' job satisfaction will be beneficial to the department. Consequently, disputes may arise within their company.

Aside from that, the questionnaire itself shouldn't be the only restriction on the data collection process. It is advised that both employers and employees participate in an interview process. In addition, it is also recommended that data be collected using technology systems such as email, Google Docs, BlogSpot, and other social media like Facebook and Twitter. This is because normally, when researchers distribute questionnaires using the technology system, it will make it easier to send them to the respondents, and the researcher will get prompt feedback from them immediately. However, there are some disadvantages to using the technology system, such as the fact that when the researcher sends the questionnaires to them, sometimes they are not delivered to them, making it difficult for the researcher to collect the data.

In this societal setting, it is important to thoroughly examine the factors behind gender roles' attitudes about work-family conflict. Researchers who are creating interventions to lessen work-family conflict and its interference may find it useful as a guide.

References

Abbas, A., Mudassar, M., Gul, A., & Madni, A. (2013). Factors contributing to job satisfaction for workers in Pakistani organization. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(1), 525.

Agarwal, R., De, P., & Ferratt, T. W. (2001). How long will they stay? Predicting an IT professional's preferred employment duration. Proceedings of the 2001 ACM SIGCPR conference on Computer personnel research. DOI:

Ahmad, A. (1996). Work-Family Conflict Among Married Professional Women in Malaysia. The Journal of Social Psychology, 136(5), 663-665. DOI:

Ahmad, A. (2008). Job, family and individual factors as predictors of work-family conflict. The Journal of Human Resource and Adult Learning, 4(1), 57-65.

Ahmad, A., & Omar, Z. (2010). Perceived family-supportive work culture, affective commitment and turnover intention of employees. Journal of American Science, 6(12), 839-846.

Al-Ajmi, R. (2006). The effect of gender on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in Kuwait. International Journal of Management, 23(4), 838.

Allen, T. D., French, K. A., Dumani, S., & Shockley, K. M. (2020). A cross-national meta-analytic examination of predictors and outcomes associated with work–family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6), 539–576. DOI:

Anderson, K. (2002). The useful archive. Learned Publishing, 15(2), 85-89. DOI:

Babin, B. J., & Boles, J. S. (1996). The effects of perceived co-worker involvement and supervisor support on service provider role stress, performance and job satisfaction. Journal of Retailing, 72(1), 57–75. DOI:

Baird, M., Ellem, B., & Page, A. (2006). Workchoices: Changes and challenges for human resource management. Thomson (Learning Australia).

Barnett, R., & Rivers, C. (2004). Same difference: How gender myths are hurting our relationships, our children, and our jobs. Basic Books/Hachette Book Group.

Beutell, N. J. (2010). Work schedule, work schedule control and satisfaction in relation to work-family conflict, work-family synergy, and domain satisfaction. Career Development International, 15(5), 501-518. DOI:

Bianchi, S. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2010). Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 705–725. DOI:

Boles, J. S., Howard, W. G., & Donofrio, H. H. (2001). An investigation into the inter-relationships of work–family conflict, family–work conflict and work satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Issues, 13(3), 376–390.

Booth, A. L., & van Ours, J. C. (2007). Job Satisfaction and Family Happiness: The Part-Time Work Puzzle. SSRN Electronic Journal. DOI:

Boyar, S. L., Maertz, C. P., Jr., Mosley, D. C., Jr., & Carr, J. C. (2008). The impact of work/family demand on work-family conflict. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(3), 215–235. DOI:

Bozo, Ö., Toksabay, N. E., & Kürüm, O. (2009). Activities of Daily Living, Depression, and Social Support Among Elderly Turkish People. The Journal of Psychology, 143(2), 193-206. DOI:

Brough, P., & O'Driscoll, M. (2005). Work-family conflict and stress. In A.-S. G. Antoniou & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Research companion to organisational health psychology (pp. 346–365). Edward Elgar Publishing. DOI:

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198. DOI:

Carlson, A. (2002). Aesthetics and the environment: The appreciation of nature, art and architecture. Routledge.

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Wayne, J. H., & Grzywacz, J. G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work-family interface: Development and validation of a work-family enrichment scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1), 131-164. DOI:

Centers, R., & Bugental, D. E. (1966). Intrinsic and extrinsic job motivations among different segments of the working population. Journal of Applied Psychology, 50(3), 193–197. DOI:

Choi, Y., Kim, Y. S., Kim, S. Y., & Park, I. J. K. (2013). Is Asian American parenting controlling and harsh? Empirical testing of relationships between Korean American and Western parenting measures. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4(1), 19–29. DOI:

Cinamon, R. G., & Rich, Y. (2002). Gender differences in the importance of work and family roles: Implications for work-family conflict. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 47(11-12), 531–541. DOI:

Duxbury, L. E., & Higgins, C. A. (1991). Gender differences in work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(1), 60–74. DOI:

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2012). Social role theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 458–476). Sage Publications Ltd. DOI:

Eby, L. T., Casper, W. J., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux, C., & Brinley, A. (2005). Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature (1980-2002). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(1), 124–197. DOI:

Fagan, C., & Burchell, B. (2002). Gender, Jobs and Working Conditions in the European Union.

Feierabend, A., Mahler, P., & Staffelbach, B. (2011). Are there Spillover Effects of a Family Supportive Work Environment on Employees without Childcare Responsibilities? Management revu, 22(2), 188-209. DOI:

Frone, M. R. (2003). Work-family balance. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 143–162). American Psychological Association. DOI:

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78. DOI:

Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and Testing an Integrative Model of the Work-Family Interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50(2), 145-167. DOI:

Frye, N. K., & Breaugh, J. A. (2004). Family-Friendly Policies, Supervisor Support, Work? Family Conflict, Family? Work Conflict, and Satisfaction: A Test of a Conceptual Model. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(2), 197-220. DOI:

Giannikis, S. K., & Mihail, D. M. (2011). Flexible work arrangements in Greece: a study of employee perceptions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(2), 417-432. DOI:

Gill, S., & Davidson, M. J. (2001). Problems and pressures facing lone mothers in management and professional occupations - a pilot study. Women in Management Review, 16(8), 383-399. DOI: 10.1108/eum0000000006290

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of Conflict between Work and Family Roles. The Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76. DOI:

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2003). When work and family collide: Deciding between competing role demands. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 90(2), 291–303. DOI:

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. The Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. DOI:

Grzywacz, J. G., & Bass, B. L. (2003). Work, family, and mental health: Testing different models of work-family fit. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(1), 248–262. DOI:

Guest, D. E. (2002). Perspectives on the study of work-life balance. Social Science Information, 41(2), 255–279. DOI:

Guest, D. E. (2004). The Psychology of the Employment Relationship: An Analysis Based on the Psychological Contract. Applied Psychology, 53(4), 541-555. DOI:

Gutek, B. A., Searle, S., & Klepa, L. (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work^family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(4), 560-568. DOI:

Hill, E. J., Erickson, J. J., Holmes, E. K., & Ferris, M. (2010). Workplace flexibility, work hours, and work-life conflict: Finding an extra day or two. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(3), 349–358. DOI:

Hill, E., Hawkins, A., Märtinson, V., & Ferris, M. (2003). Studying "Working Fathers": Comparing Fathers' and Mothers' Work-Family Conflict, Fit, and Adaptive Strategies in a Global High-Tech Company. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers, 1(3), 239-261. DOI:

Hochschild, A. R., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift. Avon.

Hodson, R. (1989). Gender differences in job satisfaction: Why aren't women more dissatisfied? The Sociological Quarterly, 30(3), 385–399. DOI:

Jain, S., & Nair, S. K. (2021). Integrating work-family conflict and enrichment: understanding the moderating role of demographic variables. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(5), 1172-1198. DOI:

Judge, T. A., Boudreau, J. W., & Bretz, R. D. (1994). Job and life attitudes of male executives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(5), 767–782. DOI:

Kao, K.-Y., Chi, N.-W., Thomas, C. L., Lee, H.-T., & Wang, Y.-F. (2020). Linking ICT Availability Demands to Burnout and Work-Family Conflict: The Roles of Workplace Telepressure and Dispositional Self-Regulation. The Journal of Psychology, 154(5), 325-345. DOI:

Karatepe, D. O. M. (2010). The effect of positive and negative work-family interaction on exhaustion: does work social support make a difference? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(6). DOI:

Kaur, T. (2012). Job satisfaction among nurses: a comparative study of nurses employed in government and private hospitals. J. Appl. Manag. Comput. Sci., 1, 1.

Khalid, S., Zohaib Irshad, M., & Mahmood, B. (2011). Job Satisfaction among Academic Staff: A Comparative Analysis between Public and Private Sector Universities of Punjab, Pakistan. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(1). DOI:

Kim, W. G., Leong, J. K., & Lee, Y.-K. (2005). Effect of service orientation on job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and intention of leaving in a casual dining chain restaurant. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 24(2), 171–193. DOI:

Kinnunen, U., & Mauno, S. (1998). Antecedents and outcomes of work–family conflict among employed women and men in Finland. Human Relations, 51(2), 157–177. DOI:

Kreiner, G. E. (2006). Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: a person-environment fit perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(4), 485-507. DOI:

Kuo, P. X., Volling, B. L., & Gonzalez, R. (2018). Gender role beliefs, work–family conflict, and father involvement after the birth of a second child. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(2), 243–256. DOI:

Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Barton, S. M. (2002). The impact of work-family conflict on correctional staff job satisfaction: An exploratory study. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 27(1), 35-52. DOI:

Lapierre, L. M., Spector, P. E., Allen, T. D., Poelmans, S., Cooper, C. L., O'Driscoll, M. P., Sanchez, J. I., Brough, P., & Kinnunen, U. (2008). Family-supportive organization perceptions, multiple dimensions of work-family conflict, and employee satisfaction: A test of model across five samples. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(1), 92-106. DOI:

Lundberg, U. (1996). Influence of paid and unpaid work on psychophysiological stress responses of men and women. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(2), 117–130. DOI:

Lyu, X., & Fan, Y. (2022). Research on the relationship of work family conflict, work engagement and job crafting: A gender perspective. Current Psychology, 41(4), 1767-1777. DOI:

McElwain, A. K., Korabik, K., & Rosin, H. M. (2005). An examination of gender differences in work-family conflict. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 37(4), 283-298. DOI:

Md-Sidin, S., Sambasivan, M., & Ismail, I. (2010). Relationship between work-family conflict and quality of life: An investigation into the role of social support. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(1), 58-81. DOI:

Miller, B. K., Wan, M., Carlson, D., Kacmar, K. M., & Thompson, M. (2022). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: A mega-meta path analysis. PLOS ONE, 17(2), e0263631. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263631

Mugunthan, S. (2013). A study of work-family conflict and job satisfaction. International Journal of Social Science & Interdisciplinary Research, 2(7), 1-12.

Netemeyer, R. G., Maxham, J. G., III, & Pullig, C. (2005). Conflicts in the Work-Family Interface: Links to Job Stress, Customer Service Employee Performance, and Customer Purchase Intent. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 130-143. DOI:

Nohe, C., Meier, L. L., Sonntag, K., & Michel, A. (2015). The chicken or the egg? A meta-analysis of panel studies of the relationship between work-family conflict and strain. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 522-536. DOI:

Parasuraman, S., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2002). Toward reducing some critical gaps in work-family research. Human Resource Management Review, 12(3), 299–312. DOI:

Pleck, J. H. (1977). The work-family role system. Social Problems, 24(4), 417–427. DOI:

Righetti, F., Sakaluk, J. K., Faure, R., & Impett, E. A. (2020). The link between sacrifice and relational and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(10), 900–921. DOI:

Sax, L. (2005). Why gender matters: What parents and teachers need to know about the emerging science of sex differences. Doubleday, New York.

Shockley, K. M., Shen, W., DeNunzio, M. M., Arvan, M. L., & Knudsen, E. A. (2017). Disentangling the relationship between gender and work-family conflict: An integration of theoretical perspectives using meta-analytic methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(12), 1601-1635. DOI:

Tennant, G. P., & Sperry, L. (2003). Work-Family Balance: Counseling Strategies to Optimize Health. The Family Journal, 11(4), 404-408. DOI:

Thompson, E. R., & Phua, F. T. T. (2012). A Brief Index of Affective Job Satisfaction. Group & Organization Management, 37(3), 275-307. DOI:

Van Ruysseveldt, J., Verboon, P., & Smulders, P. (2011). Job resources and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of learning opportunities. Work & Stress, 25(3), 205-223. DOI:

Voydanoff, P. (1980). Perceived job characteristics and job satisfaction among men and women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 5(2), 177–185. DOI:

Voydanoff, P. (2002). Linkages between the work-family interface and work, family, and individual outcomes: An integrative model. Journal of Family Issues, 23(1), 138–164. DOI:

Watson, I., Buchanan, J., Campbell, I., & Briggs, C. (2003). Fragmented futures: New challenges in working life. Annandale: Federation Press.

Wiersma, U. J. (1994). A Taxonomy of Behavioral Strategies for Coping with Work-Home Role Conflict. Human Relations, 47(2), 211-221. DOI:

Wongsuwan, N., Phanniphong, K., & Na-Nan, K. (2023). How Job Stress Influences Organisational Commitment: Do Positive Thinking and Job Satisfaction Matter? Sustainability, 15(4), 3015. DOI:

Woodruffe, C. (2006). The crucial importance of employee engagement. Human Resource Management International Digest, 14(1), 3-5. DOI:

Yee, R. W. Y., Yeung, A. C. L., & Edwin Cheng, T. C. (2010). An empirical study of employee loyalty, service quality and firm performance in the service industry. International Journal of Production Economics, 124(1), 109-120. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 May 2024

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-132-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

133

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1110

Subjects

Marketing, retaining, entrepreneurship, management, digital marketing, social entrepreneurship

Cite this article as:

Jacob, G. A. D., Sundram, V. P. K., & Othman, A. K. (2024). Work-Family Conflict and Satisfaction: Does Gender Matters?. In A. K. Othman, M. K. B. A. Rahman, S. Noranee, N. A. R. Demong, & A. Mat (Eds.), Industry-Academia Linkages for Business Sustainability, vol 133. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 846-858). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2024.05.69