Abstract

Religiosity is an increasingly attractive theme in academia, with a growing research interest in recent years. This attention is crucial for theoretical advancement and tapping into Muslim consumer markets. Though an essential aspect of culture, conceptualising religiosity has been challenging at many levels. Thus, researchers adopted a conventional perspective to operationalise such measures, especially in understanding Muslim consumers. The objective of this paper is twofold. Firstly it assesses the trends in the development of religiosity measurement or scales for Muslims. Secondly it explores the empirical relationships of religiosity with other exogenous variables in consumer behaviour research. It eventually discuss the pitfalls of such adoption and further highlight avenues in developing specific measurements catering to Muslim consumer research. Methodologically, it employs a systematic literature review to explain essential aspects of Muslim religiosity. This paper identified two main pitfalls concerning the conceptual and operational aspects of the measurements. As importantly, it discussed these gaps and proposed potential avenues for improvement. Ultimately, it provides new insight into Muslim religiosity measurements.

Keywords: Consumer research, Muslim religiosity, Muslim consumer, religiosity measurement pitfalls

Introduction

Religion is an important cultural element and social institution that is universal and most significant in influencing attitudes, values, and behaviour (Mokhlis, 2006; Rafiki & Wahab, 2014). Research on religion and consumers in Muslim consumer markets has focused more on religiosity. Recent trends have shown that the world is developing towards a global renaissance of organised religiosity (Arnould et al., 2004; Armstrong, 2011). Most studies in various disciplines include religiosity in predicting human behaviour, including consumer behaviour research. Thus, it has been a popular theme used by most researchers.

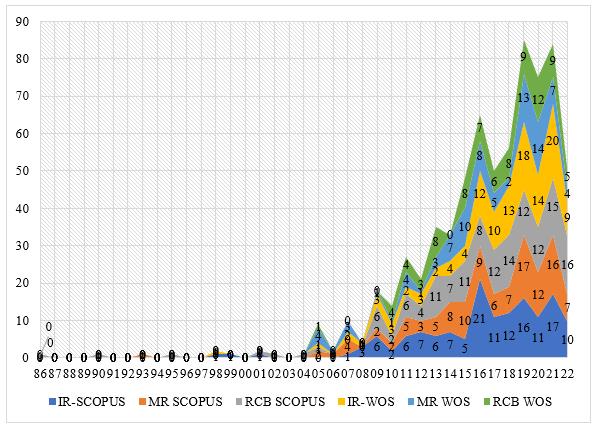

Research on the topic is growing in momentum shown in Table 1. As of January 2022, there were 2,797,000 studies on religiosity indexed in Google Scholar. The publication trend recorded an increase of 50.6% in January 2022 compared to January 2020, with an average increment of 10% over the past three years. More stringent databases such as WoS and Scopus showed a steady climb from January 2020 to January 2022 with 16.6% and 23.6% respectively. Some studies specifically scrutinised Islamic and Muslim religiosity. However, this is still relatively small in number, lying within the average of 0.64 % (Google Scholar), 0.71% (WoS), and 0.79% (Scopus) in each of these databases. Religiosity from an Islamic perspective remains limited (Mokhlis, 2006; Newaz, 2014; Shukor & Jamal, 2013).

This paper conducted a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) that revealed a limited but growing number of studies concerning religiosity for Muslims. This included 113 selected studies on the topic covered from 1997 to 2020 through the screening and exclusion process, with 31 studies focused on religiosity measurement and scales for Muslims. Furthermore, 86 studies identified had featured religiosity in various frameworks incorporating religiosity. At least 26 performed theory-testing research suggesting the different roles of religiosity.

Problem Statement

The primary concern is that existing measures are inadequate to capture the concept of religiosity in researching Muslim consumers. The main reason is the unclear measurement of Muslim consumer religiosity at conceptual and operational levels. Conceptually, conventional definitions and conceptualisation influenced its conception in various studies, thus shaping the operationalisation of these measures in research concerning Muslim consumers. Such is evident from the substantial adaptations of universal measurements often characterised by uncritical justifications and a lack of consideration.

Most researchers adapted well-established religiosity measurements (Allport & Ross, 1967; Stark & Glock, 1968; Wilkes et al., 1986; Worthington et al., 2003). Even though these measurements originated from different contextual settings catering to specific religions and perspectives based on Judeo-Christian and Western cultural perspectives, these researchers widely preferred such measures to those of Muslim origin, despite the pitfalls of these so-called universal measurements criticised over the years (Berry, 2005; Cohen et al., 2012; King & Crowther, 2004). This indicates the lack of critical consideration in these adaptations and limits insights on the nature of religiosity suitable for Muslim consumers.

Furthermore, these adaptations resulted in considerable religiosity measurements operationalised to Muslim consumers. Though they were multidimensional measures, they were modified and fitted into a single dimension to suit different contexts of the study (Dekhil et al., 2017; Iranmanesh et al., 2019; Kusumawardhini et al., 2016; Mokhlis, 2006; Mansori et al., 2015). Some also adopted a gross measure of religiosity derived from Wilkes et al. (1986) in their research (Ahmed et al., 2013; Abdolvand & Azima, 2015; Moschis & Ong, 2011). Such operationalisations may not reflect the actual phenomenon of religiosity for Muslims I

Research Questions

- Are the existing measurements sufficient to capture the phenomenon of Muslim consumer religiosity?

- Is there a need for new and improved religiosity measurement for Muslim consumers?

- This study addressed these two research questions, and both will be discussed in detail in the next sections.

Purpose of the Study

The objective of this study is twofold. Firstly, it assesses the trends in the development of religiosity measurement or scales for Muslims. Secondly, it explores the empirical relationships of religiosity with other exogenous variables in consumer behaviour research. Thus, it highlights the pitfalls of the current religiosity measurements and further improvement to develop better measurements to cater to Muslim consumers' research.

Research Methods

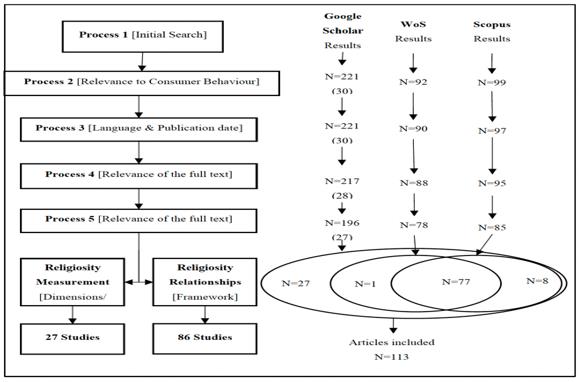

This study employed a systematic literature review (SLR) to revisit religiosity measurements for Muslims. This process commenced in January 2020 and until the end of February 2020. It involved a four-step process and modified stages of extracting and synthesising data from the SLR. It consisted of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion (ISEI) based on the Preferred Reporting Items Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) method (Moher et al., 2009). This process also assisted with the modified stages of thematic review (Yao et al., 2022; Zairul, 2020). As shown in Figure 1, the identification process starts with the initial search based on the search string in Process 1. Multiple databases were utilised, including WoS and Scopus and extended to Google Scholar to ensure sufficient coverage based on the keywords. This is due to limited findings based on the keywords alone for information searching exhibited in Table 2.

The process starts with the search string or the identification of keywords. Based on the objectives mentioned earlier, the search centred on religiosity for Muslim consumers. At this stage, the identification process utilised “Muslim religiosity” and “Islamic religiosity”. It scrutinised synonyms and variations that are closely related and represent religiosity for Muslims. Initially, it involved searching in two well-established databases that have a stringent level of quality for publications. Nonetheless, limited studies on these topics require more diverse searching techniques and databases, especially on the development of measurements of Muslim religiosity.

The review also employed additional searching using more general search engines/databases such as Google Scholar and Proquest. Proquest is relevant since it provides copies of research reports/full-text theses. This process also emphasised the context of consumer behaviour research in Process 2. This study screened 131 studies, 31 identified as suitable for measurement development for item generation (16 indexed in Scopus and 17 indexed in WoS and 13 in Google Scholar). Then checked for duplication (15 articles were indexed in both Scopus and WoS, 2 in Scopus, and 1 in WoS). As mentioned earlier, an additional search was employed using more general databases (i.e., Google Scholar), resulting in 13 being screened for their relevance to consumer behaviour and consumer research. Of these thirteen studies, five were full-text theses, and eight were peer-reviewed articles but not indexed in either Scopus or WoS.

Another 100 articles were scrutinised based on their relevance to the topic, context and content on religiosity and its relationships. It helps the researcher to conceptualise the framework. This study focuses on the roles and effects of religiosity on various endogenous variables in consumer research, especially attitude, intention, and behaviour. It also focuses on the theoretical backdrops of this research which is crucial for the rationale of theoretical foundations. Despite the careful and systematic selection, this study excluded two articles at this stage due to redundancy. This rectification resulted in a data set of 128 articles.

Other than that, process 3 screened out non-English articles and full-text theses as the criteria for the selection. It also limits the publication date ranging from 1997 to 2020. As shown in Figure 2, this study observed the trend of publication that started in 1997 to 2020. It recorded a steady climb from 2009 to the present, especially in both Scopus and WoS databases based on the determined keywords. Thus, the recent surge in attention will justify the selection period of these studies.

Furthermore, process 4 and 5 further checked the eligibility of these studies by subjecting the full-text contents to further analysis. Process 4 screened the full-text articles or theses for mention of measurement development or Muslim consumer religiosity. This study excluded four at this stage, with two articles indexed in Google Scholar and two studies indexed both in WoS and Scopus. A total of 27 were suitable for measurement development and utilised in the construct validation stage (indexed in Google Scholar, WoS, and Scopus). These studies were screened for their aim, sample sizes and representativeness, dimensions, and items.

Lastly, Process 5 specifically focused on exploring the relationships of religiosity with other dependent variables. 86 studies were highly relevant and suitable for achieving the objectives of this study. At this stage, twelve studies were excluded (9 indexed both in Scopus and WoS, one indexed only in Scopus, one indexed only in WoS and one in Google Scholar). In overall, the inclusion process resulted in 113 indexed studies (77 studies indexed in both WoS and Scopus, one study indexed in WoS, eight studies indexed only in Scopus, and 27 studies indexed only in Google Scholar). 27 out of the 113 studies were selected for measurement development purposes (13 studies indexed in Scopus and WoS, 1 study indexed in WoS, 2 indexed in Scopus and 11 indexed in Google Scholar). The remaining 86 studies were selected to explore the religiosity relationships to other dependent variables (64 studies indexed both in WoS and Scopus, six indexed in Scopus only, and sixteen indexed in Google Scholar).

Findings

Aim of Measurement Development

In general, the development of Islamic religiosity measurements provide an alternative to Western methods. According to Manap et al. (2013), developing religiosity for Muslims is based on Islamic principles and teachings. Researchers acknowledge that such gaps exist between conventional religiosity concepts and the proposed religiosity and measurements for Muslims (Albelaikhi, 1997; Abu Raiya et al., 2008; Jana-Masri & Priester, 2007; Qasmi & Jahangir, 2011). Most researchers developed these instruments in a specific context and field within psychology.

In contrast, the Islamic Behavioural Religiosity Scale (IBRS) (Abou-Youssef et al., 2011), proposed market-minded religiosity that had an almost similar justification to Ul-Haq et al. (2019) to suit a growing number of researchers that use religiosity as a variable in their research, especially in Muslim consumer research (Usman et al;, 2017). Besides that, the Islamic Religiosity Measurement is one of the specific religiosity measurements to suit consumer research (Dali et al., 2019; Shukor & Jamal, 2013). These measurements offer a different perspective on religiosity previously conceptualised in psychology since they focused on behavioural aspects that correspond to consumer research.

Dimensions and Items

According to Ul-Haq et al. (2019), determining the number of dimensions is one of the challenges in developing religiosity measures for Muslims. As shown in Table 3, most studies are often exploratory. It is prevalent that these studies developed each measurement or scale using exploratory factor analysis, EFA. These dimensions vary and range from two to six, with the number of items from 16 to 101. Based on 27 scales, three employed CFA (Abou-Youssef et al., 2011; Olufadi, 2017; Shukor & Jamal, 2013). According to Albelaikhi (1997), studies can further develop the measurement of religiosity by using confirmatory analyses.

These measurements and scales focus on several dimensions such as religious belief/central tenets, Islamic behavioural/ practices/ commitment/ Ibadat, the societal value of religion/religious altruism and enrichments. These dimensions are named differently, but further examination shows similarities in the concepts and items. Dali et al; (2019) found that two of the most suggested religiosity dimensions are beliefs and practices. Manap et al. (2013) emphasised that the standard of development of the measurement must refer to Al Quran and As-Sunnah. Belief and Commitment/Practices are mentioned repeatedly in Al Quran on (faith) and (Good deeds) (Dali et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, most studies in consumer research employed a single-dimensional religiosity measurement. This gross measurement was adapted from mixed measures developed into a single dimension to suit the context of consumer research (Abd Rahman et al., 2015; Awan et al., 2015; Shah Alam & Mohamed Sayuti, 2011). Most of the studies used such measures though the need to measure religiosity beyond a single generic measure was voiced by several studies (Muhamad Hashim & Mizerski, 2010; Muslichah et al., 2019). According to Muslichah et al. (2019), there has been concern about this (Khraim, 2010; Shukor & Jamal, 2013). Few studies have focused on developing an instrument tailored to consumer or marketing research since current studies still adapted a single dimension with items ranging from 3 to 9, as shown in Table 4.

Other than that, there are several attempts to use multidimensional measures of religiosity (Briliana & Mursito, 2017; Farrag & Hassan, 2015; Newaz, 2014; Rehman & Shabbir, 2010). These studies employed a religiosity measurement based on Glock (1972). Similarly, most studies adopted measures from well-established religiosity measurements (Allport & Ross, 1967; Wilkes et al., 1986; Worthington et al., 2003). This measure operationalised between 1 to 3 dimensions, with items ranging from 3 to 27 items. Instead of reinventing the wheel, most studies widely preferred to adopt these measures. However, to what extent do these measures manifest actual religious belief? Or capture behavioural aspects beyond ritual practices, since the standard of these measurements must be based on Al Quran and As-Sunnah (Khraim, 2010; Manap et al., 2013).

A close examination of the modified ROS revealed that such modifications follow Islamic or Muslim religiosity. However, it fell short in capturing the whole concept of Islamic or Muslim religiosity (Mokhlis, 2006). Several studies adapted Wilkes et al. (1986), despite the multidimensional nature of religiosity found across many studies. It is a single dimension measurement occasionally adopted by researchers. Moschis and Ong (2011) acknowledged this and admitted that such adoption may not capture all the theoretically relevant dimensions of religiosity constructs. Not to mention, it also employed multi-religious respondents who differ in their beliefs and practices, thus highlighting the particularism in religiosity measures that suit such respondents. It highlights the issue of universalism versus particularism of these measures.

Assessment of Relationships

Some research on religiosity in psychology solely focused on developing the instrument (Albelaikhi, 1997; Jana-Masri & Priester, 2007; Olufadi, 2017). Several were developed in consumer and business research (Abou-Youssef et al., 2011; Dali et al., 2019; Shukor & Jamal, 2013; Ul-Haq et al., 2019). These measurements need to be utilised and replicated to measure Muslim religiosity. Though useful references for Muslim or religiosity measurements, they are limited to instrument development with no assessment of impact on dependent variables.

On the other hand, some measurements developed in psychology were assessed with other intended variables (Abu Raiya et al., 2008; Ihsan et al., 2017; Krauss et al., 2005; Tiliouine & Belgoumidi, 2009). PMIR tested several variables such as general satisfaction, well-being, purpose in life, good physical health, lower depressed mood, lower angry feelings, lower alcohol abuse, and good physical health (Abu Raiya et al., 2008). Besides, CMIR tested variables such as Meaning of Life and Subjective Well-being (SWB) (Tiliouine & Belgoumidi, 2009). Also, MRPI developed and assessed the impact on nation-building (Krauss et al., 2005) and RRHM was developed to see the relationship to behavioural deviation.

Besides that, most of the studies utilised various adapted religiosity measurements. These single-dimensional measures often assessed the impact of religiosity on variables such as new product adoption, Halal purchase intention, undertaking Islamic banking selection (Awan et al., 2015; Abd Rahman et al., 2015; Shah Alam & Mohamed Sayuti, 2011; Shah Alam et al., 2012; Rehman & Shabbir, 2010). These studies might suffer from making the inappropriate conclusion of demonstrating such relationships. Thus, employing such gross measures might limit the multidimensional effects on specific consumer behaviour variables.

Furthermore, a close examination of 86 studies incorporating religiosity in various theoretical and conceptual frameworks concerning Muslim consumers has shown several key findings. As shown in Table 5, 22.6% of the studies had employed TPB as their theoretical framework, while 7.5% had used TRA. These two were the most used underlying theories in researching Muslim consumers. As the background factors of religiosity, 11.11% of its impact focused on attitude, and additionally, 23.32% focused on intention and 10.10% focused on behaviour.

In addition, findings from these articles on the relative importance of religiosity yielded mixed results. Depending on the variable ranging from four to six predictors, 26.9% of the studies found religiosity ranked as the most significant variable relative to other variables, especially the TPB determinants (i.e., attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control). 15.4% of the studies ranked religiosity relatively as the second most significant variable. It was also ranked the third and fourth most important variable, with 7.7% and 3.8% respectively.

Based on relative importance, from the 26.9% of the studies that found religiosity was the main predictor of intention, the strength of beta has an average of 0.384. Compared to studies that found religiosity as the second most significant predictor of purchase intention, the average beta strength was 0.298. Lesser average beta values for the third or fourth were 0.086 and 0.039 respectively. Overall, religiosity was found not to be the most significant predictor in 38.4% of the studies. 11.5% found it insignificant, 11.5% found that it moderated the relationship between independent and dependent variables and 23.1% did not rank the importance of religiosity.

Moreover, 24.7% (24 articles) of the studies had applied various kinds of theories. These theories include the Functional Theory of Attitudes, Human Basic Values Theory, Theory of Islamic Consumer Behaviour, Retail Patronage Behaviour, Transaction Utility Theory, COO and Brand Familiarity Framework, Kendal’s Consumer Style Inventory, Pro-Environmental Consumer Behaviour (PECB) and Halal Label Food Shopping Behaviour to mention a few. 23.7% of the studies proposed their own framework or model. 21.5% of the studies were not clearly specified in terms of the theory used in their studies. Other than that, almost half of 46% of these publications focused on the impact of religiosity on various independent variables. Nevertheless, the various uses of different religiosity measurements might not reflect the conceptualisation and relationship (Abou-Youssef et al., 2011; El-Bassiouny, 2016; Khraim, 2010; Shukor & Jamal, 2013). Many findings might draw incomplete conclusions when incorporating single-dimensional religiosity in assessing its impact. It also limited the understanding of measures from different ideologies and perspectives affecting its ability to manifest the religiosity of Muslim consumers. Thus, it warrants more studies on religiosity for Muslims assessing its impact on specific behaviour.

The Pitfalls of Religiosity Measurements

Conceptual

According to Berry (2005), the pitfalls of religiosity and spirituality or RS measurements are threefold: construct measurements, study design and data analysis. Though previous critiques exist in physical and psychological health studies, the development and use of religiosity in consumer research is increasing, especially among Muslim consumers. Religiosity measurement for Muslims would face similar methodological challenges. This study discussed only two pitfalls, focusing on the construct measurements, and study design. It only focuses on Islamic and Muslim religiosity measurements that exist in the fields of psychology, business or consumer research.

Firstly, the challenges in construct measurement are from conceptual and operational perspectives. Conceptually, researchers have agreed that religiosity is a highly abstract construct. Thus, finding a conceptually and consistently clear definition of religiosity has been challenging. Though researchers proposed various definitions, only Manap et al. (2013) defined religiosity from an Islamic perspective. Nonetheless, Manap et al. (2013) provide a different conceptual model, arguably distinct, thus posing a challenge to the content validity of the non-Western Muslim religiosity constructs (Ul-Haq et al., 2019).

The complexity of RS has received extensive discussion (Berry, 2005; King & Crowther, 2004). One of the main issues is the inconsistency of definitions, which remains perhaps unresolved. Manap et al. (2013) proposed a model to approach the concept from an Islamic perspective. It focused on outward aspects that set up a boundary to current conceptualisations. Religiosity is multidimensional and individual traits are manifest and reflected in practices and behaviour. Therefore, most religiosity measurements for Muslims consist of belief and practices (Dali et al., 2019; Ul-Haq et al., 2019). To date, there exists no agreed number of such dimensions, both from conventional and Islamic perspectives (Mokhlis, 2006).

Operational

Furthermore, operationally, researchers proposed many dimensions of Muslim religiosity. Nonetheless, its operationalisation has been varied and extends its lack of clarity. These constructs are often multidimensional measures of various aspects of Muslim belief, commitment and affiliation. Berry (2005) stated the possible bipolar dimensions to identify primary characteristics of various operationalisations of religiosity. It includes substance versus function, theocentric versus non-theocentric and universalism versus particularism.

In the case of substance vs function, it is often challenging to balance between measuring the substantive and functional aspects of religiosity. The substantive measures approach to religiosity focuses on characteristics such as belief, relationship to the divine and one’s view of self, others, and the world. This may push the boundaries between scientific theory and theology (Berry, 2005). Functional approaches often focus on behaviour and response and tend to erode definitional boundaries if not tied to substantive belief. This leads to construct validity issues. Ul-Haq et al. (2019) acknowledge that it is one of the most difficult challenges in developing religiosity measurement.

Moreover, the inconsistencies in measuring both substantive and functional measures or between Islamic beliefs and practices pose a challenge to the methodological approach of current operationalisations. Development of constructs of beliefs and practices will consider appropriate items concerning the context of the phenomenon. According to Berry (2005), questionnaire items related to a substance must conform to the belief system, and functional items need to tie directly to substantive belief (Berry, 2005). Abou-Youssef et al. (2011) suggested that a questionnaire can describe religion by asking the respondents about their religious affiliation or preferences. Authors suggest associational techniques used in psychology.

In addition, such a construct applies to all Muslims since every Muslim is supposed to possess such a fundamental belief. The operationalisation of current constructs employed items that depict pillars of faith in Islam. Any measurement focusing on such a substantive dimension may get zero variation. Thus, modifying the question using this technique might offer a solution to such a construct. Usman et al. (2017) demonstrated modification of religiosity adopted from Tiliouine and Belgoumidi (2009). These researchers modified the items for religious beliefs with more suitable measures focusing on the manifestation of one’s religious belief in Islamic banking.

Furthermore, current functional measures would influence the respondents to answer with higher bias when distributing questionnaires using face-to-face interaction. These items include measuring behavioural practices such as “I pray five times a day” and “I regularly fast during Ramadan”. The concern is with private and confidential information on substantive or functional measures of religious beliefs and ritualistic aspects of the sample which would sometimes be misleading and not precise (Abou-Youssef et al., 2011). It increases the chance of manipulation due to socially desirable responses (Albelaikhi, 1997; Abou-Youssef et al., 2011).

Besides that, there is a theocentric versus a non-theocentric approach. Muslim religiosity requires a theocentric operationalisation. Muslims submit to Allah and are central to their religiosity, embodying the concept of the Tawhidic paradigm. Thus, religiosity from an Islamic perspective is theocentric. The bipolar dimension of the non-theocentric approach might not apply to these religiosity measures. Unlike conventional religiosity, Muslims are convinced of Allah and do not assume the existence of another higher power.

Next, most researchers focusing on Muslim consumer research adapted religiosity measurements with the universalism approach (Allport & Ross, 1967; Wilkes et al., 1986; Worthington et al., 2003). These researchers aimed for universal measures to suit the different backgrounds of the respondents. The universalism approach suggests a broad view of religiosity measures. It is operationalised to as many persons as possible that often transcend culture and religion. In contrast, particularism calls for the development of measures for specific groups of like-minded people to capture a particular expression valued by that group. Particularism seems a more suitable dimension when developing and employing religiosity measures for Muslims.

Besides this, the universalism of religiosity measurement can only exist within the Muslim population. It does not transcend religion, but it is more than likely to transcend Muslim cultures. Albelaikhi (1997) highlighted demographic challenges in developing appropriate items. It also includes the sensitivity and offensiveness of religiosity measures from cultural or political landscapes. It must consider the social, cultural, and religious context to avoid the operationalisation problem (Abou-Youssef et al., 2011; El-Bassiouny, 2016; Khraim, 2010). Thus, researchers need to ensure the soundness of measures. Besides, avoiding such issues requires a deep understanding of the population for intended measurement (Ul-Haq et al., 2019).

Implication for Future Research

Development of Multidimensional religiosity for Muslims

A more rigorous approach to derive multidimensional aspects of Muslim consumer religiosity is warranted. The use of EFA to derive such factors must be accompanied using more stringent factor reduction to reduce the initial constructs utilising parallel analysis (Green et al., 2016). Besides, such measurement should employ CFA procedure to confirm that the new factors possessed reliability and validity for the model validity. Thus, it is expected that the deletion of items of post-EFA might be a better fit into the measurement and structural model for future research. Further improvement can consider these items for item pooling of an improved instrument in different contextual settings.

Moreover, the development of items can perhaps be carried out using a variety of approaches. For instance, Dali et al. (2019) employed expert opinion using Q sorting for this procedure in ensuring construct validity. Despite no focus group interviews, their instrument was further validated and refined using a single data collection before EFA. Besides that, others employed refinement of a specific measurement (Abou-Youssef et al., 2011; Amer, 2021). Other than that, future research could investigate the new factors to uncover detailed reasons by employing qualitative research, such as an in-depth interview. Even though the focus group interviews elicit essential themes for the item generations, they might fall short of detailed discussion on the factors. Further investigation of the new factors is crucial in understanding how it shapes Muslim consumer behaviour. Thus, this study recommends exploratory, explanatory sequential mixed method research, or convergent design to provide in-depth insights on these factors

Furthermore, this study recommends employing advanced statistical techniques relevant to instrument development. It provides an avenue for choosing suitable SEM techniques for CFA, including CB-SEM and PLS-SEM. In terms of developing a new infant measurement model, PLS-SEM seems better. Though relatively similar in large sample sizes, CB-SEM reported lower construct reliability and validity values than PLS-SEM. PLS-SEM uses a different statistical assumption than CB-SEM. It is more suitable for retaining more predictors (items) with higher construct reliability and validity values crucial in developing a good fit measurement model.

Extension of Current Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

A substantial number of studies proposed modified frameworks to research the impact of religiosity. TRA and TPB have been the favoured basis for these frameworks. Iranmanesh et al. (2021) reported in their SLR that 45% of these frameworks adopted TPB (39%) and TRA (4%), with 45% unfounded by any theory. According to this study, almost 10% employed different theoretical backdrops ranging from Social Identity Theory, Consumption Theory, Self-congruity Theory, and Social Exchange Theory. The SLR for this study also produced similar findings with TRA and TPB.

Furthermore, since TRA and TPB dominate the theoretical foundations of these works, 52% of these studies focused on purchase intention as the dependent variable, followed by attitude (15%) and consumption (9%). While among the most explored determinants (independent variables) are the customer-related factors, followed by religion-related factors (mostly on religiosity) and product-related factors. Iranmanesh et al. (2021) called for a combination of more theories, such as the Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory and Social Cognitive Theory and TPB. Thus, this study recommends that future research go beyond TRA and TPB.

Moreover, Iranmanesh et al. (2021) suggested focusing on several essential variables shaping the perception of Muslim consumers. This includes aspects such as quality, perceived values, reputation, and word of mouth. These are some aspects of brand preferences addressed in this study as part of the building block of the RELBRAINT framework. Choosing TICB and TOHADEMAP as the underlying theories, the attention to religiosity and preferences of Muslim consumers can give deeper insight beyond the Intention-behaviour framework (derived from TRA and TPB). Therefore, this research contends that the new framework can provide more empirical evidence to support these theories.

This study reinforces the recommendation by Iranmanesh et al. (2021) to integrate more theories such as Social-Organism-Response Theory and Social Cognitive Theory, which are currently only 1% of the overall research literature. More studies also need to focus on Social Identity Theory, the third most used theory after TPB and TRA. For instance, Anas (2019) employed Social Identity Theory and Social Impact Theory to explore the role of norms in predicting the attitude and behaviour of individuals. Future research should emphasise the impact of social and norms-related factors since social responsiveness and norms are essential aspects of religiosity and Muslim consumer behaviour. Thus, this study recommends integrating multiple rationales in extending the current framework of Muslim consumer behaviour.

Conclusion

In conclusion, highlighting the gap of constructs measurements and the need for an improved measurement in consumer research enable better insight and conceptualization of religiosity for Muslims. It will broaden the perspective on religiosity and assessment of its multidimensional effect with the new development of such measurement. It provides an alternative to current religiosity measurements modified in a limited way to suit consumer research settings. Identifying the new Muslim consumer religiosity factors will provide better-operationalised items and capture a broader religiosity concept currently limited to religious belief and ritual practices. Thus, it deals with the conceptual and operational challenges to provide new measurements highlighting previously overlooked factors.

References

Abd Rahman, A., Asrarhaghighi, E., & Ab Rahman, S. (2015). Consumers and Halal cosmetic products: knowledge, religiosity, attitude and intention. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 6(1), 148-163

Abdolvand, M. A., & Azima, S. (2015). The role of ethnocentrism, religiosity, animosity, and country-of-origin image, in foreign product purchase intention case study: buying Saudi products by Iranian consumers. International Journal of Marketing & Financial Management, 3(11), 71-93.

Abou-Youssef, M., Kortam, W., Abou-Aish, E., & El-Bassiouny, N. (2011). Measuring Islamic-driven buyer behavioural implications: a proposed market-minded religiosity scale. Journal of American Science, 7(8), 728-741

Abu Raiya, H., Pargament, K. I., Mahoney, A., & Stein, C. (2008). A psychological measure of Islamic religiousness: Development and evidence for reliability and validity. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 18(4), 291-315

Acas, S. S., & Loanzon, J. I. V. (2020). Determinants of Halal Food Purchase Intention among Filipino Muslims in Metro Manila. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 10(3), 1- 7.

Ahmed, Z., Anang, R., Othman, N., & Sambasivan, M. (2013). To purchase or not to purchase US products: role of religiosity, animosity, and ethnocentrism among Malaysian consumers. Journal of Services Marketing, 27(7), 551-563

Albelaikhi, A. A. (1997). Development of a Muslim Religiosity Scale [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Rhode Island

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4), 432-443.

Amer, M. M. (2021). Measures of Muslim Religiousness Constructs and a Multidimensional Scale. In: A. L. Ai, P. Wink, R. F. Paloutzian, & K. A. Harris, (Eds.). Assessing Spirituality in a Diverse World. Springer.

Anas, A. (2019). Complying with religious codes: Investigating religiosity and consumer behaviour [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Queensland University of Technology.

Armstrong, K. (2011). The battle for God: A history of fundamentalism. Ballantine Books.

Arnould, E., Price, L., & Zikhan, G. (2004). Consumers (2nd Ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Awan, H. M., Siddiquei, A. N., & Haider, Z. (2015). Factors affecting Halal purchase intention – evidence from Pakistan’s Halal food sector. Management Research Review, 38(6), 640-660

Berry, D. (2005). Methodological pitfalls in the study of religiosity and spirituality. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 27(5), 628-647.

Briliana, V., & Mursito, N. (2017). Exploring antecedents and consequences of Indonesian Muslim youths' attitude towards halal cosmetic products: A case study in Jakarta. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(4), 176-184.

Cohen, M. Z., Holley, L. M., Wengel, S. P., & Katzman, R. M. (2012). A platform for nursing research on spirituality and religiosity: definitions and measures. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 34(6), 795-817.

Dali, N. R. S. M., Yousafzai, S., & Hamid, H. A. (2019). Religiosity scale development. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 10(1), 227-248.

Dekhil, F., Boulebech, H., & Bouslama, N. (2017). Effect of religiosity on luxury consumer behaviour: the case of the Tunisian Muslim. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 8(1), 74-79

El-Bassiouny, N. (2016). Where is “Islamic marketing” heading? A commentary on Jafari and Sandikci (2015). “Islamic” consumers, markets, and marketing. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 569- 578.

Farrag, D. A., & Hassan, M. (2015). The influence of religiosity on Egyptian Muslim youths’ attitude towards fashion, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 6(1), 95-108.

Glock, C. Y. (1972). On the study of religious commitment. In J. E. Faulkner (Ed.). Religion’s Influence in Contemporary Society: Readings in the Sociology of Religion, (pp. 38-56). Merril.

Green, J. P., Tonidandel, S., & Cortina, J. M. (2016). Getting through the gate: Statistical and methodological issues raised in the reviewing process. Organisational Research Methods, 19(3), 402-432.

Hanafiah, M. H., & Hamdan, N. A. A. (2021). Determinants of Muslim travellers Halal food consumption attitude and behavioural intentions. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 12(6), 1197-121

Ihsan, H., Herlina, M., & Chotidjah, S. (2017). The Validation of Skala Ritual Religious Harian Muslim (Daily Moslem Religious Rituals Scale). Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Social and Political Development (ICOSOP 2016).

Iranmanesh, M., Mirzaei, M., Parvin Hosseini, S. M., & Zailani, S. (2019). Muslims' willingness to pay for certified halal food: an extension of the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(1), 14-30. DOI:

Iranmanesh, M., Senali, M. G., Ghobakhloo, M., Nikbin, D., & Abbasi, G. A. (2021). Customer behaviour towards halal food: a systematic review and agenda for future research. Journal of Islamic Marketing. Ahead-of-print.

Jana-Masri, A., & Priester, P. E. (2007). The development and validation of a Qur’an-based instrument to assess Islamic religiosity: The religiosity of Islam scale. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 2(2), 177-188.

Khan, A., Azam, M. K., & Arafat, M. Y. (2019). Does religiosity really matter in purchase intention of Halal certified packaged food products? A survey of Indian muslims consumers. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 27(4), 2383-2400

Khraim, H. (2010). Measuring religiosity in consumer research from an Islamic perspective. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 2(2), 166-179.

King, J. E., & Crowther, M. R. (2004). The measurement of religiosity and spirituality: Examples and issues from psychology. Journal of Organisational Change Management, 17(1), 83-101

Krauss, S. E., Hamzah, A., Juhari, R., & Hamid, J. A. (2005). The Muslim Religiosity-Personality Inventory (MRPI): Towards understanding differences in the Islamic religiosity among the Malaysian youth. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 13(2), 173-186

Kusumawardhini, S. S., Rahayu, S., Hati, H., & Daryanti, S. (2016). Understanding Islamic Brand Purchase Intention: The Effects of Religiosity, Value Consciousness, and Product Involvement [Proceeding]. BE-ci 2016: 3rd International Conference on Business and Economics. Selangor Malaysia

Manap, J. H., Hamzah, A., Noah, S. M., Kasan, H., Krauss, S. E., Mastor, K. A., Suandi, T., & Idris, F. (2013). Prinsip Pengukuran Religiositi Dan Personaliti Muslim [Principles of Muslim Religiosity and Personality Measurement]. Jurnal Psikologi dan Pembangunan Manusia, 1(1), 36-43.

Mansori, S., Sambasivan, M., & Md-Sidin, S. (2015). Acceptance of novel products: the role of religiosity, ethnicity and values. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(1), 39–66

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535-b2535.

Mokhlis, S. (2006). The influence of religion on retail patronage behaviour in Malaysia [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Sterling.

Moschis, G. P., & Ong, F. S. (2011). Religiosity and consumer behaviour of older adults: A study of subcultural influences in Malaysia. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(1), 8-17

Muhamad Hashim, N., & Mizerski, D. (2010). Exploring Muslim consumers' information sources for fatwa rulings on products and behaviors. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1(1), 37-50.

Muslichah, M., Abdullah, R., & Razak, L. A. (2019). The effect of halal foods awareness on purchase decisions with religiosity as a moderating variable: A study among university students in Brunei Darussalam. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(5), 1091-1104.

Newaz, F. T. (2014). Religiosity, Generational Cohort and Buying Behaviour of Islamic Financial Products in Bangladesh [Unpublished doctoral dissertation].Victoria University of Wellington.

Olufadi, Y. (2017). Muslim Daily Religiosity Assessment Scale (MUDRAS): A new instrument for Muslim religiosity research and practice. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 9(2), 165-179.

Qasmi, F. N., & Jahangir, F. (2011). Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Religiosity Scale for Muslims. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 4(2), 99-110.

Rafiki, A., & Wahab, K. A. (2014). Islamic values and principles in the organisation: A review of the literature. Asian Social Science, 10(9), 1-7.

Rehman, A., & Shabbir, M. S. (2010). The relationship between religiosity and new product adoption. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1(1) 63-69.

Saptasari, K., & Aji, H. M. (2020). Factors affecting Muslim non-customers to use Islamic bank: Religiosity, knowledge, and perceived quality. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Keuangan Islam, 6(2), 165-180. DOI:

Shah Alam, S., & Mohamed Sayuti, N. M. (2011). Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in halal food purchasing. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 21(1), 8-20.

Shah Alam, S., Janor, H., Zanariah, C. A. C. W., & Ahsan, M. N. (2012). Is religiosity an important factor in influencing the intention to undertake Islamic home financing in Klang Valley? World Applied Sciences Journal, 19(7), 1030-1041.

Shukor, S. A., & Jamal, A. (2013). Developing scales for measuring religiosity in the context of consumer research. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 13(1), 69-74.

Souiden, N., & Jabeur, Y. (2015). The impact of Islamic beliefs on consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions of life insurance. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 33(4), 423-441. DOI:

Stark, R., & Glock, C. Y. (1968). American piety: The nature of religious commitment. University of California Press.

Tiliouine, H., & Belgoumidi, A. (2009). An exploratory study of religiosity, meaning in life and subjective well-being in Muslim students from Algeria. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 4(1), 109-127.

Ul-Haq, S., Butt, I., Ahmed, Z., & Al-Said, F. T. (2019). The scale of religiosity for Muslims: an exploratory study. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(6), 1201-1224.

Usman, H., Tjiptoherijanto, P., Balqiah, T. E., & Agung, I. G. N. (2017). The role of religious norms, trust, importance of attributes and information sources in the relationship between religiosity and selection of the Islamic bank. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 8(2), 158-186. DOI:

Wilkes, R. E., Burnett, J. J., & Howell, R. D. (1986). On the meaning and measurement of religiosity in consumer research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 14(1), 47-56.

Worthington, E. L., Jr., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., Schmitt, M. M., Berry, J. T., Bursley, K. H., & O'Connor, L. (2003). The Religious commitment inventory-10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counselling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 84–96.

Yao, P., Osman, S., Sabri, M. F., & Zainudin, N. (2022). Consumer behaviour in online-to-offline (O2O) commerce: A thematic review. Sustainability, 14(13), 7842.

Zairul, M. (2020). A thematic review on student-centred learning in studio education. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(2), 504-511.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 May 2024

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-132-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

133

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1110

Subjects

Marketing, retaining, entrepreneurship, management, digital marketing, social entrepreneurship

Cite this article as:

Abdullah, J. B., Abdullah, F., & Bujang, S. B. (2024). The Pitfalls of Religiosity Measurements in Muslim Consumer Research. In A. K. Othman, M. K. B. A. Rahman, S. Noranee, N. A. R. Demong, & A. Mat (Eds.), Industry-Academia Linkages for Business Sustainability, vol 133. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 721-736). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2024.05.59