Abstract

Microfinance concept was introduced by Prof Muhammad Yunus in 1970s with the aspiration to provide financial services to the poor. To assist the poor, it is vital for the microfinance scheme to be sustainable. A sustainable microfinance scheme shall be self-sufficient, financially, and operationally for both parties, the institutions and the recipients (microentrepreneurs who received the microfinance service) as well. However recently, microfinance institutions (MFIs) have been frequently criticized as prioritizing profit over the care of their poor recipients (microentrepreneurs). Therefore, there is a need for MFI to have a good governance that able to bridge the interests of both MFI and recipients. The focus of this concept paper is to understand the current governance mechanism of KUR program by the Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) in monitoring the disbursement and repayment of the microfinance. As the only MFI in Indonesia with government credit guarantee scheme, this concept paper provides an overview on the governance of KUR program in improving the income level of their recipients.

Keywords: Effectiveness, Government Credit Guarantee Scheme, Governance, Microfinance

Introduction

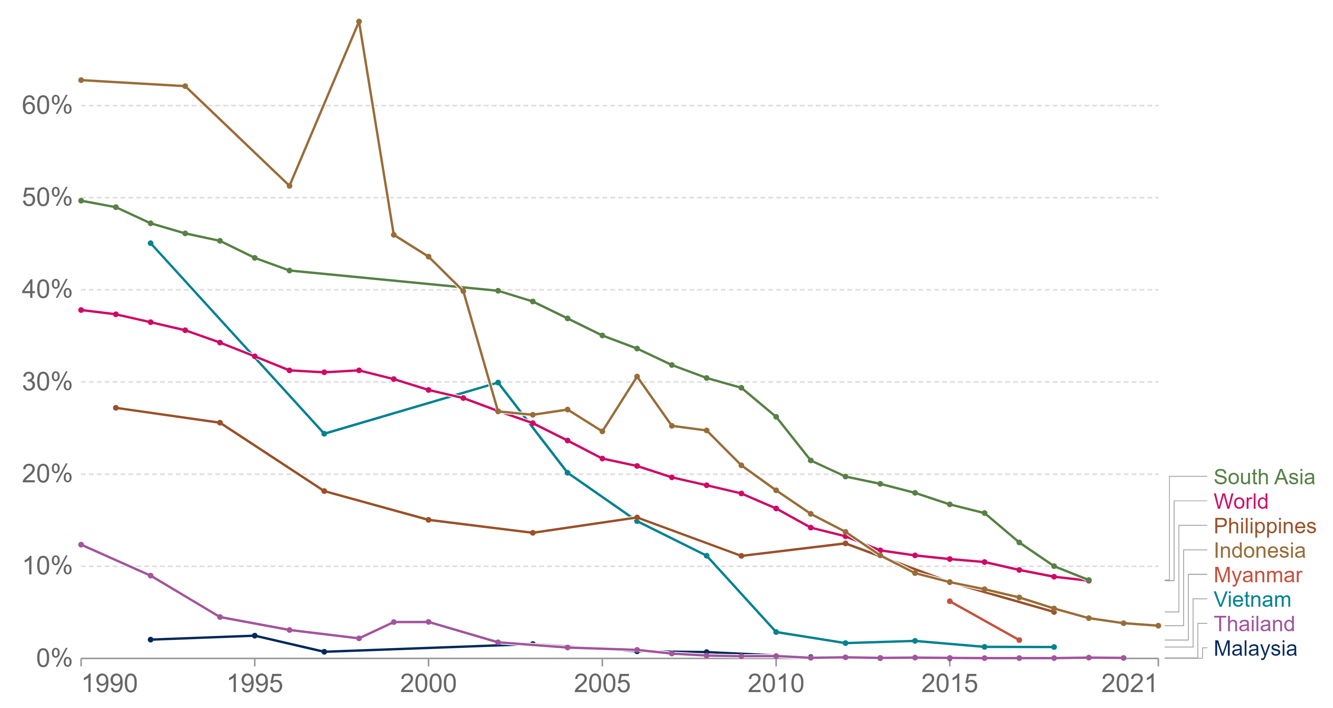

Since its widespread introduction in the 1980s through Grameen Bank by Muhammad Yunus in Bangladesh, microfinance has experienced significant growth (Yunus, 2007). Acknowledged for its potential in reducing poverty, microfinance aims to empower individuals and uplift communities. In September 2022, the World Bank updated the international poverty line to $2.15 per day from $1.90 in 2015. The updated figure is based on the new Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). Based on this updated figure, it means that anyone living on less than $2.15 a day is considered as living in extreme poverty. In 2019, approximately 648 million people globally were in this situation. Figure 1 below summarizes the percentage of extreme poverty incidence in the selected countries in South East Asia as compared to the world (as shown in pink line) and South Asia (as shown in green line) based on the International Poverty Line of $2.15 per day. Referring to the figure, in 1990, it was reported that 37.81% of world population were living in extreme poverty, as compared to 49.67% in South Asia. During the period, 62.75% of Indonesian and 12.35% of Thai were living in extreme poverty. As shown in Figure 1, since then, the percentage is declining in the majority of countries in the South East Asia. In 2015, it was reported that the percentage of extreme poverty in the world was 10.79%, South Asia (16.71%), Philippines (8.29%), Indonesia (8.28%), Vietnam (1.26%), Thailand (0.05%), and Malaysia (0.02%).

Referring to the empirical research on the impact of the microfinance programmes worldwide, it shows that MFIs have been producing positive results for their borrowers or recipients. For instance, Pitt and Khandker (1998) observed that microfinance programs had greater impacts on women, while Karlan and Zinman (2009) reported higher impacts of the First Macro Bank in Manila, Philippines, specifically on men, particularly in terms of business profits. Interestingly, this study also revealed that the microfinance institution (MFI) had a more pronounced impact on higher-income entrepreneurs. The findings of Karlan and Zinman (2009) regarding the heightened impact of microfinance on higher-income participants were similarly supported by Coleman (1999). Examining the effects of Rural Friends Association (RFA) and Foundation for Integrated Agricultural Management (FIAM) programs in Northeast Thailand, Coleman's study found positive impacts on savings, incomes, productive expenses, and labor time for the wealthier participants. Furthermore, recent studies by Gill (2014) in India, Iqbal et al. (2015) in Pakistan, Maity (2023) in India, Rokhim et al. (2023) in Indonesia, and Ülev et al. (2023) in Turkey also revealed a positive relationship between microfinance programs and socio-economic development and poverty alleviation in their respective study areas. Table 1 below summarizes the selected impact studies on various MFI worldwide.

Despite the attention given to microfinance's impact on poverty alleviation, there remains an unresolved issue regarding the design of the credit contracts. Furthermore, ongoing debates persist about the effectiveness of microfinance schemes in the form of individuals or joint groups (Block, 2012; Giné & Karlan, 2014; Hartungi, 2007; Morduch, 2000). Only limited studies have focused on the governance and sustainable financial development of micro and small enterprises within microfinance schemes (Bayai & Ikhide, 2018; Yasin, 2020).

The concept of microfinance dictates that MFI should contribute to the development of sustainable economic and financial systems by providing credit to recipients who are typically excluded from traditional banking system (Akram & Routray, 2013; Lopatta et al., 2017; Rathore, 2015; Ullah & Khan, 2017; Weber & Ahmad, 2014). However, in recent years, some MFIs have prioritized profit over the welfare of their impoverished recipients (Fishman, 2020; Rahim Abdul Rahman, 2010; Rathore, 2015, 2017; Toindepi, 2016). Therefore, there is an urgent need for a sustainable credit scheme that aligns the interests of microfinance institutions and recipients, ensuring a mutually beneficial situation for both parties. Therefore, the focus of this paper is to review the governance and effectiveness of Indonesia's microfinance program, known as KUR.

Microfinance and Kredit Usaha Rakyat (KUR), Indonesia

In the late nineteenth century, microfinance in Indonesia took its initial steps with the establishment of the Bank Kredit Rakyat and Lumbung Desa by the government. These institutions aimed to assist farmers, workers, and laborers in achieving self-sufficiency and avoiding exploitative loan practices. Bank Kredit Rakyat was later renamed as the Village Bank in 1905, expanding its services to encompass non-agricultural economic activities. In 1929, the Village Credit Board (BKD) was created through the East Indies Government Gazette No. 137, tasked with administering rural credit programs in Java and Bali (SMERU, 2006). After Indonesia gained independence, the central government supported the establishment of 'market' banks (bank pasar) and micro credit formed by local governments. These institutions included the Rural Credit and Funds Institutions (LDKP) in West Java, the Districts Credit Board (BKK) in Central Java, the Credit for Small-scale Businesses (KURK) in East Java, the Lumbung Pitih Nagari (LPN) in West Sumatra, and the Village Credit Institution (LPD) in Bali. During this period, they were not yet recognized as MFIs; instead, they were referred to as bank pasar (or market), village bank, or districts credit institutions. However, a significant change occurred in the finance landscape in the 1990s when Law No. 07 of 1992 on banking regulations and non-bank financial institutions was enacted, defining only two types of banks recognized in Indonesia; Commercial Banks and Rural Banks (BPR) (Patten et al., 2001).

Microfinance development in Indonesia experienced rapid growth with the launch of the KUR program in early November 2007. This government initiative aimed to provide capital access for Micro, Small, Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), and Cooperatives by disbursing credit funds from the bank's own resources, backed by credit guarantee institutions. Under the KUR program, credit risk is shared between participating banks (30%) and the credit guarantee institution (70%), with the government obligated to pay a guaranteed premium of 1.5% from the State Budget (Aristanto et al., 2020).

The Minister of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia issued Regulation No. 10/PMK.05/2009, which specified the KUR program as credit or working capital financing and/or investment schemes intended for MSMEs without requiring collateral. The main goal was to enhance MSMEs' access to financing sources and stimulate national economic growth. However, despite being designed without collateral requirements, the implementation of the KUR program still adhered to standard banking practices, such as loan applications with collateral, file selection based on eligibility, and approval of loan amounts with specific interest rates (Atmadja et al., 2018).

The primary objective of the KUR program is to accelerate economic development in the real sector, contributing to poverty reduction and providing employment opportunities. As part of their commitment to community-based economic empowerment, the government issued a Policy Package to improve the Real Sector and Empower MSMEs (Atmadja et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the KUR program has been occasionally misinterpreted as direct government assistance with free money, leading to potential hidden risks associated with this policy.

Initially, the KUR Program was a pro-poor policy aimed at broadening access to capital through formal financial institutions. However, as the program evolved, several policy changes were introduced, affecting various fundamental aspects, such as loan schemes, program recipients, and implementers (Aristanto et al., 2020; Hartungi, 2007; Hamidi & Salahudin, 2021; SMERU, 2006; Sujarweni & Utami, 2015; Santoso & Gan, 2019; Yasin, 2020).

To achieve sustainability, the KUR program must maintain effective financial performance and social objectives. This is vital for both microfinance institutions and microenterprises in securing their working capital and investment funds from the government (Farida et al., 2015). Ensuring good governance in the disbursement and repayment of loans is crucial for the KUR Program, aligning with the government's policies aimed at creating employment, income equity, poverty alleviation, climate development, business independence, and economic growth. As such, this study seeks to review the effectiveness of the KUR program in Indonesia and the current governance mechanisms implemented for monitoring the disbursement and repayment of microcredit sustainability.

Governance of Kredit Usaha Rakyat (KUR)

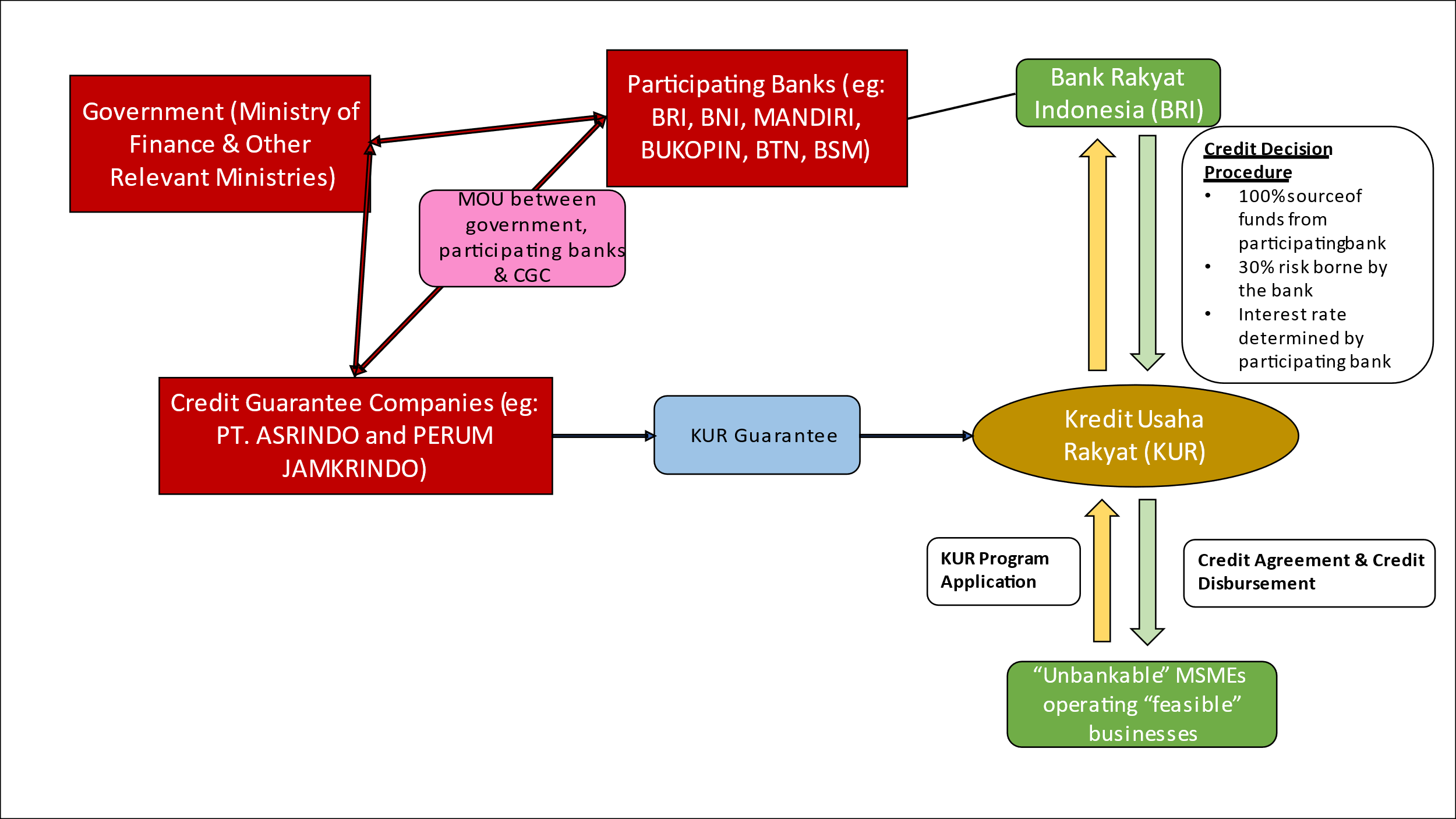

The Indonesian government introduced Kredit Usaha Rakyat (KUR) (translated as People’s Business Credit) in November 2007. This initiative serves as a government guarantee scheme with the primary goal of supporting MSMEs and cooperatives in accessing bank loans. KUR provides both working capital credit, with a maximum repayment term of three years, and investment credit, with a maximum term of five years, all at attractive low-interest rates. While there is a possibility of loan extensions, they are only allowed under specific circumstances. Initially, the yield curve for KUR micro (credit ceiling per debtor up to Rp25 million or USD1,7000) was set at 22% per annum, and for KUR retail (credit ceiling between Rp25 million and Rp500 million or USD1,700 and USD33,130 per debtor), the interest rate was placed at 14% per annum. However, these rates were subsequently reduced to 12% and further to 9% for both schemes (Tambunan, 2018). Remarkably, the KUR program does not require a business license or collateral from the applicants. The only documents needed are the applicant's identity card and an official letter from the village leader. Under this program, the government provides a guarantee that covers around 70% to 80% of the credit applied for, while the remaining risk is assumed by the participating bank, such as Bank Rakyat Indonesia (Tambunan, 2018). Figure 2 below illustrates the governance mechanism of KUR program at Bank Rakyat Indonesia in monitoring the disbursement and prepayment of the microfinance.

KUR was established by three parties: the Indonesian government, represented by the Ministry of Finance and other related ministries; participating banks (for instanceand; and Credit Guarantee Companies (CGCs) such as Asrindo and Jamkrindo. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was created to govern the KUR mechanism principles and establish an effective working relationship among these three parties. This MoU also outlines the working scopes and responsibilities of each involved party.

Based on the MoU, the Indonesian government encourages KUR disbursement in two ways. First, specific ministries provide information on potential KUR borrowers to participating banks across all economic sectors. Second, the Ministry of Finance allocates a portion of the state budget to pay the credit guarantee fee to the two state-owned CGCs (known as Askrindo and Jamkrindo) and the two local government owned CGCs (Jamkrida Jatim and Jamkrida Bali). The Ministry of Finance also allocated a state capital injection to enhance the technical capacity of the two state-owned CGCs in implementing the partial credit guarantee scheme. The credit guarantee fee and state capital infusion enable CGCs to act as the government's agent by providing a partial credit guarantee to cover the lending risks of KUR loans, which are between 70% and 80%.

The KUR disbursement mechanism is outlined in the MOU's chapter on its Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). According to the SOP, it begins when "unbankable" MSMEs, operating "feasible" businesses within productive sectors, apply to borrow KUR loans from participating banks. "Unbankable" refers to the situation where a potential borrower is unable to meet the credit requirements of the participating banks, particularly the collateral requirements. On the other hand, "feasible" denotes a potential borrower who has been engaged in a consistent and profitable business for at least six months, indicating their ability to repay the loan within the predetermined timeframe and grow the business.

Following the receipt of loan applications, participating banks conduct a screening procedure based on their own assessment of credit risk and in accordance with micro-prudential requirements to choose and approve reasonable applications, adhering to a commercial-banking approach. This effort aims to reduce market failures caused by information asymmetry. Subsequently, the participating banks fund KUR loans entirely with their own money (the banks' deposit) after application approval. Simultaneously, KUR borrowers commit to signing a transaction contract, obliging them to repay the bank's principal and interest loans within a predetermined timeframe. According to the terms of the transaction contract, KUR borrowers also agree to use KUR loans solely to expand their investments or improve their working capital for productive purposes.

Banks submit an application to CGCs on behalf of the designated KUR borrowers to be included in a partial credit guarantee scheme. For further information, CGCs issue the guaranteed certificate used to submit the guarantee fees (IJP) to the government (Ministry of Finance) at an annual rate of 3.25 percent. Participating banks submit a credit default claims application to CGCs when SME borrowers fall behind on their loan payments (credit under status of collectability 4 and 5 status). The credit default claim is paid to the banks by CGCs after verification is complete. The CGCs reduce banks' reluctance to lend to "unbankable" MSMEs by offering a partial guarantee program to assist them.

KUR can be distributed directly to MSMEs by participant banks or indirectly through linkage institutions such as savings and loan cooperatives, secondary cooperatives, village credit agencies (BKD), (BMT), (BPRS), other recognized non-bank financial institutions, venture groups, and microfinance institutions. In 2015, the government introduced some changes to improve the scheme, such as implementing a cap on the highest KUR lending rates at 12% annually (7% for KUR micro and 3% for KUR retail). Additionally, the IJP was replaced with an interest rate subsidy. The sector coverage was expanded to include all trade activities, not just limited to agriculture, fishery, and industrial manufacturing. Furthermore, financing was made available for the placement of Indonesian migrant workers (TKI) abroad, with a maximum ceiling of Rp25 million (USD1,700) and a 12% interest rate subsidy. KUR is a government-guaranteed credit program designed to assist "feasible yet unbankable" MSMEs in obtaining banking loans. Improved access to banking loans could stimulate MSMEs to enhance their competitiveness, enabling them to play a greater role in creating jobs and generating income for the poor and near poor.

Conclusion

This paper reviews the governance mechanism of the KUR program in Indonesia that involve three (3) main parties, namely Indonesia government, participating banks, and CGC. It was found that the governance mechanism for the KUR program, as followed by bank participants, adheres to the regulations set forth by the Indonesian government. However, it is observed that its implementation by participating banks is not entirely aligned with the primary objectives of the program. This disconnect arises from the participating banks' need to comply with micro-prudential banking requirements, leading to reluctance in extending KUR loans to poor households. This apprehension is based on their concern that providing access to KUR loans for the poor might lead to an increase in bad credit cases. Based on the analysis presented in this paper, there are two key areas for improvement. Firstly, it is crucial to enhance the design of KUR to achieve sustainability, ensuring it serves as an effective microcredit scheme for MSMEs in Indonesia. Although KUR has helped mitigate banks' risk aversion, its impact remains limited due to banks' inability to adequately assess the risks associated with lending to MSMEs. Therefore, it is recommended that banks adopt a set of criteria for MSMEs before granting a KUR loan. This could include evaluating business plans and ensuring the proper utilization of the loan funds.

References

Akram, S., & Routray, J. K. (2013). Investigating causal relationship between social capital and microfinance: Implications for rural development. International Journal of Social Economics, 40(9), 760-776.

Aristanto, E., Khouroh, U., & Ratnaningsih, C. S. (2020). Dinamika Kebijakan Program Kredit Usaha Rakyat (KUR) di Indonesia [Dynamics of People’s Business Credit Program (KUR) Policy in Indonesia]. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Kewirausahaan, 8(1), 85–95.

Atmadja, A. S., Sharma, P., & Su, J.-J. (2018). Microfinance and microenterprise performance in Indonesia: an extended and updated survey. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(6), 957-972.

Bayai, I., & Ikhide, S. (2018). Financing Structure and Financial Sustainability of Selected Sadc Microfinance Institutions (MFIs). Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 89(4), 665–696.

Block, W. E. (2012). Micro-finance: a critique. Humanomics, 28(2), 92-117.

Coleman, B. E. (1999). The impact of group lending in Northeast Thailand. Journal of Development Economics, 60(1), 105-141.

Farida, F., Siregar, H., Nuryartono, N., & Intan, K. P., E. (2015). Micro enterprises’ access to people business credit program in Indonesia: Credit rationed or non-credit rationed? International Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2), 57–70.

Fishman, J. (2020). Microfinance - Is There a Solution: A Survey on the Use of MFIs to Alleviate Poverty in India. Denver Journal of International Law & Policy, 40(4), 4.

Gill, G. K. (2014). Microfinance and Poor: A Case Study of District Sangrur. International Journal of Regional Development, 1(1), 79.

Giné, X., & Karlan, D. S. (2014). Group versus individual liability: Short and long term evidence from Philippine microcredit lending groups. Journal of Development Economics, 107, 65-83.

Hamidi, M. L., & Salahudin, F. (2021). An Alternative Credit Guarantee Scheme for Financing Mses In Islamic Banking. Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance, 7(1).

Hartungi, R. (2007). Understanding the success factors of micro-finance institution in a developing country. International Journal of Social Economics, 34(6), 388–401.

Iqbal, Z., Iqbal, S., & Mushtaq, M. A. (2015). Impact of microfinance on poverty alleviation: The study of District Bahawal Nagar, Punjab, Pakistan. Management and Administrative Sciences Review, 4(3), 487-503.

Karlan, D. S., & Zinman, J. (2009). Expanding Microenterprise Credit Access: Using Randomized Supply Decisions to Estimate the Impacts in Manila. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Li, X., Gan, C., & Hu, B. (2011). Accessibility to microcredit by Chinese rural households. Journal of Asian Economics, 22(3), 235-246.

Lopatta, K., Tchikov, M., Jaeschke, R., & Lodhia, S. (2017). Sustainable Development and Microfinance: The Effect of Outreach and Profitability on Microfinance Institutions' Development Mission: Sustainable Development and Microfinance. Sustainable Development, 25(5), 386-399.

Maity, S. (2023). Financial inclusion also leads to social inclusion—myth or reality? Evidences from self-help groups led microfinance of Assam. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(1).

Mokhtar, S. H. (2011). Microfinance Performance in Malaysia. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Lincoln University.

Morduch, J. (2000). The Microfinance Schism. World Development, 28(4), 617-629.

Patten, R. H., Rosengard, J. K., & Johnston, J. (2001). Microfinance success amidst macroeconomic failure: The experience of bank Rakyat Indonesia during the East Asian crisis. World Development, 29(6), 1057–1069.

Pitt, M. M., & Khandker, S. R. (1998). The impact of Group-Based Credit Programs on Poor Households in Bangladesh: Does the Gender of Participants Matter? Journal of Political Economy, 106(5), 958-996.

Rahim Abdul Rahman, A. (2010). Islamic microfinance: An ethical alternative to poverty alleviation. Humanomics, 26(4), 284–295.

Rathore, B. S. (2015). Social capital: Does it matter in a microfinance contract? International Journal of Social Economics, 42(11), 1035–1046.

Rathore, B. S. (2017). Joint liability in a classic microfinance contract: review of theory and empirics. Studies in Economics and Finance, 34(2), 213–227.

Rokhim, R., Lubis, A. W., Faradynawati, I. A. A., Perdana, W. A., & Deni Yonathan, A. (2023). Examining the role of microfinance: a creating shared value perspective. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 39(2), 379-401.

Santoso, D. B., & Gan, C. (2019). Microcredit Accessibility in Rural Households: Evidence from Indonesia. Economics and Finance in Indonesia, 65(1), 67.

SMERU. (2006). Policy brief: Microfinance in Indonesia. https://www.smeru.or.id/sites/default/files/publication/microfinance_eng.pdf

Sujarweni, V. W., & Utami, L. R. (2015). Analisis Dampak Pembiayaan Dana Bergulir KUR (Kredit Usaha Rakyat) Terhadap Kinerja UMKM [Impact Analysis of Revolving Fund Financing (People’s Business Credit) on MSMEs Performance]. Jurnal Bisnis Dan Ekonomi (JBE), 22(1), 11–24.

Tambunan, T. T. H. (2018). The performance of Indonesia’s public credit guarantee scheme for MSMEs: A regional comparative perspective. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, 35(2), 319–332.

Toindepi, J. (2016). Investigating a best practice model of microfinance for poverty alleviation: Conceptual note. International Journal of Social Economics, 43(4), 346-362.

Ülev, S., Savaşan, F., & Özdemir, M. (2023). Do Islamic microfinance institutions affect the socio-economic development of the beneficiaries? The evidence from Turkey. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 39(2), 286-311.

Ullah, I., & Khan, M. (2017). Microfinance as a tool for developing resilience in vulnerable communities. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 11(2), 237-257.

Weber, O., & Ahmad, A. (2014). Empowerment through microfinance: The relation between loan cycle and level of empowerment. World Development, 62, 75–87.

Yasin, M. Z. (2020). The Role of Microfinance in Poverty Alleviations: Case Study Indonesia. Airlangga International Journal of Islamic Economics and Finance, 3(2), 76.

Yunus, M. (2007). Muhammad Yunus - Banker to The Poor_ Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty –PublicAffairs. PublicAffairs.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 November 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-130-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

131

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1281

Subjects

Technology advancement, humanities, management, sustainability, business

Cite this article as:

Panjinegara, P., Nadzri, F. A. A., & Yusuf, S. N. S. (2023). Governance of Kredit Usaha Rakyat, A Microfinance With Government Credit Guarantee Scheme. In J. Said, D. Daud, N. Erum, N. B. Zakaria, S. Zolkaflil, & N. Yahya (Eds.), Building a Sustainable Future: Fostering Synergy Between Technology, Business and Humanity, vol 131. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1041-1050). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2023.11.85