Abstract

The study is aimed to analyze the role of bullying experience to understand the motivation of interpersonal interaction in adolescence. Adolescence as the period of self-determination requires active and numerous interaction and communication with other people, especially peers, as the source of psychological development. The experience of social interaction can be very different and includes potential risks for teenagers. Bullying behavior is one of the dangerous forms of social interaction in adolescence. We analyzed the peculiarities of understanding the bullying behavior motivation by adolescents with different experience in bullying. We used the cinema material due to the fact that video content is more vivid and emotionally close to the spectator. 149 adolescents from several schools took part in the investigation. The method included the film review and psychosemantic technique called 'behavior motives attribution’. Subjects were divided into several groups according to the bullying experience in their real life. After the film review the most emotional episodes were defined. The specific understanding of motivation of antihero by adolescents with different experience of bullying in real life was revealed.

Keywords: Bullying, films, adolescence

Introduction

Informational socialization is the main form to enter the adult social world and acquire meanings for modern adolescents. Large amount of information incoming via various communication channels, defines the social and cultural realm of human existence (Martsinkovskaya, 2012). Video and Internet content becomes one of the key information environments and allows one to get acquainted with the experience of other people, try it and then evaluate its importance. The possibility to build a virtual world of communication, interaction and education strongly determines the nature of risks and opportunities of adolescents’ socialization (Molchanov et al., 2019; Soldatova & Rasskazova, 2014). The key psychological process in adolescence is self-determination. Self-determination can be considered both as the process and the result. The specific status of adolescent ('no longer a child, not yet an adult') leads to the uncertainty of role behavioural patterns that are defined through self-search (Molchanov, 2016). The interpersonal relations, especially relations with peers, play a crucial role in self-esteem development and identity processes. The development of the main psychological structures, such as the sense of adulthood as per the Elkonin model, the ego-identity as per the E. Erikson model, means that stable and sustainable self-concept is developed alongside with one's values and life goals (Elkonin, 1989; Erikson, 1980). Self-knowledge as a complex process of self-search and role experimentation under the moratorium conditions ensures the possibility to know oneself through comparing to others and learn about oneself in different behavioural models.

One of the important channels of informational socialization are movies, especially the fiction genre. The development of digital world increased the availability of fiction films and expanded the opportunities to fully or partially view of video content and uncontrolled movies choice. There are various number of studies of the impact of movies on children and adolescents. The aggressive behaviour of film characters under certain conditions can increase the aggressive behaviour of viewers, as the classical experiments of A. Bandura on children audience have shown. The modern meta-analysis of various studies of the relationship between the psyche and movies with a large number of violent scenes has shown that regular demonstration of verbal and physical aggression, aggressive thoughts as well as planning of children's and adolescents' actions correlates with watching such films. The consumption of alcohol, tobacco or drugs by the film characters is also connected with the corresponding movies plots (as cited in Anderson et al., 2003; Kulick & Rosenberg, 2001; Stern, 2005). Movies’ analysis usually emphasises on their harmful impact on adolescent audience. This is determined by the age and psychological specifics of normative adolescents’ development when teenagers are very sensitive to the film content. However, apart from the negative effects that video content has on psychological and personal development of adolescents, there is another paradigm of studying the cinema impact on psychological development of children and adolescents. In particular, cinematherapy as a form of psychological practice becomes popular in work with adolescents (Bierman et al., 2003). The use of film metaphorical language and sometimes direct demonstration of complicated and painful topics intersecting with real-life and further discussion might be quite efficient to overcome existing emotional experience of adolescents (Marsick, 2010). There is evidence that the use of cinematherapy with adolescents that experiences divorce trauma, parents' separation or physical death of a loved one can be effective to overcome crisis (Sharp et al., 2002). The effectiveness of cinematography in working with emotional disorders and social problems of adolescents was also noted (Dole & McMahan, 2005). Some researchers are considering to use films in preventing cyberbullying (Nabila et al., 2021).

Problem Statement

During the interaction with peers adolescents can participate in bullying behaviour. Different position in bullying participation can lead to different psychological effects in future, mostly negative. The issues of bullying and cyberbullying prevention and averting are relevant topics in modern psychology and pedagogy (Sobkin & Smyslova, 2014). There are various attitudes towards understanding of intensity decrease of bullying behaviour. In particular, much attention is paid to increase the level of moral sensitivity to bullying, understand behavioural motives, to take into account the conditions, know the behavioural strategy and opportunities to find social support (Rest et al., 1999; Tongsuebsai et al., 2015). The adolescent orientation in bullying conditions is based on the ability to identify with the characters, their motivation and on the situation itself.

Fictional text is arranged in such a way that in its culmination the conflicts are most intensive, the plot turning point is outlined and the whole piece is ready for unbinding. This film culmination results in the audience catharsis - the main aesthetic reaction leading to 'discharge of the emotions that have just been evoked'. In this regard, one of the cinema image functions is to actualize the empathic response to the characters' behaviour. Studies show that movie watching promotes empathy which displays itself in the interaction with other people in real life (Khusumadewi & Juliantika, 2018). Empathy is an important personal quality in prevention of bullying and cyberbullying (Doumas & Midgett, 2020). It is known that demonstration of video material for analysis significantly transforms the understanding of the situation in comparison with conventional forms of material presentation (Podolskiy, 2005). As a result, video content can contribute to greater immersion into the considered issue and its reflexion. The general reduction of uncertainty in evaluation of the situation participants, situation content and its consequences are important for bullying and cyberbullying behaviour correction.

Research Questions

3.1. To define the film episodes that arouses the strongest emotions in adolescence

3.2. To analyze the adolescents’ understanding of antihero motivation with different bullying experience in real life.

Purpose of the Study

This study is aimed to analyze how bullying experience influences on understanding of motivation in interpersonal relations. We highlighted the hypothesis that the audience with real life school bullying experience perceived the core idea of movie choosing specific episodes that reveal, according to them, the underlying concept of the film. At the same time, extremely emotional perception of the episode is caused by its composition and structure and is understood by any audience quite uniformly.

Research Methods

The data included 149 subjects (students of grades 8 and 10). The subjects were divided into five groups: boys and girls with no bullying experience; schoolers who had experienced school bullying as 'bullies'; schoolers who had experienced school bullying as 'victims'; schoolers who had been 'witnesses'.

The research included watching the feature film called 'Scarecrow' by R. Bykov, which describes adolescent school bullying. The film content is the story about adolescents’ group aggression from the first bullying situations to the highest level. The adolescents depicted the culmination point of the film, which reveals the most powerful emotions and we use the psychosemantic technique to define 'behaviour motives attribution' of two main characters in the culminating scene. As part of the psychosemantic technique, the subjects were given the list of potential motive for the action of the main antihero bully. They were asked to evaluate the possibility of attribution on a six-point scale (from 0 to 5). The technique also showed the following motives: 'desire to be a leader (to command)', 'desire to remain loyal', 'desire to help', 'need for attention', 'fear of punishment', 'sense of duty', 'striving to be free in judgement and actions' etc., - a total of 32 motives.

Findings

The first task was to determine the culmination point of the film that caused the most intense emotions. The results for the 5 episodes that induce strongest emotional reaction are presented in the Table 1.

The diverse audience replies were analyzed: 17 episodes were mentioned. One episode stands out clearly - when children set the scarecrow on fire. This episode appears most often in subjects’ responses, regardless of the position in school with regard to bullying: 50% among 'victims', 46.1% among 'witnesses' and 42.8% among 'bullies'. Schoolers with no personal bullying experience also mention this episode often - 32,3 %. The scene mentioned by adolescents was also the most important for the film director. According to the respondents, the fire episode is "an extremely artistic solution". The scene was necessary according to the art logic. It acted as a psychological limit to which the creators had to bring both the characters and the audience; encourage the victim to active resistance and let the bullies know where some misinterpreted idea and moral deafness led them to; and powerfully and almost shockingly awake the audience self-consciousness.

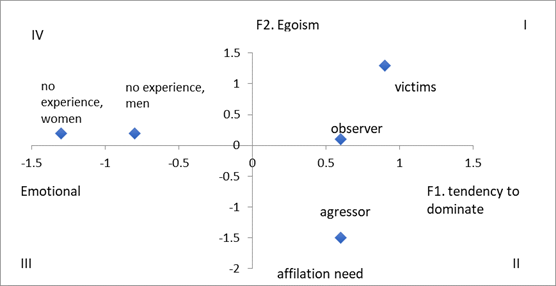

After selecting the culmination scene, subjects determined the motives of the main antihero. As a result of the factor analysis of the average matrix data, four bipolar factors that determine the understanding of the motivational structure of the bully behaviour were identified: F1 (40,9%) 'tendency to dominate– affiliation need'; F2 (26,8%) 'egoism – affiliation need', F3 (25,1%) 'readiness for interaction - ego-protection'; F4 (7,1%) 'fear - sense of regret'. The identified factors clearly differentiate the ideas about the motivation of antihero behaviour among adolescents with different experiences of bullying. For illustrative purposes, here are various subsamples of the subjects with regard to two factors - F1 ('tendency to dominate– affiliation need') and F2 ('egoism – affiliation need') - that determine the actions of the bully-antihero when he set the scarecrow on fire (Figure 1).

Viewers with no experience of bullying (both boys and girls) have zero values on the F2 factor axis 'egoism', i.e., these motivational tendencies in the behaviour of the antihero are neither found nor mentioned. When describing bully's behaviour, they tend to attribute him the motives that determine the negative pole of the F1 factor ('emotional acceptance): 'mercy', 'sense of justice', 'sense of love'. That indicates an inadequate understanding of his action in this situation. Adolescents with no bullying experience significantly differ from teenagers with school bullying experience The responses of both 'victims', 'bullies', 'witnesses' are placed on the positive pole of the F1 factor ('tendency to dominate'). This pole is determined by motives: 'desire to be a leader', 'desire to demonstrate superiority, 'need for self-affirmation'. This motivation is very typical for the antihero, who was used to taking a leadership position in the class and was trying to recover his status in this situation. That means that the bullying experience helps audience to attribute the behaviour motivation of the film character more adequately.

The responses of subjects with different bullying experience are placed differently on the axis of the F2 factor ''egoism – affiliation need'. The responses of 'witnesses', as well as viewers without experience in bullying, have zero values on the F2 factor axis, i.e., as we have already noted, these motivational trends in the behaviour of the antihero are not recorded by them. At the same time, F2 factor clearly polarizes the 'victims' and 'bullies' understanding of bully behaviour motivation. The opinions of the 'bullies' are placed on the negative pole of F2 factor (affiliation need'). This pole is determined by the following motives: 'following the norms of this social group', 'desire to be like everyone else, not to stand out', 'desire to arouse sympathy, 'desire to be a good friend', etc. The responses of the 'victims' were, on the contrary, placed on the positive pole of the F2 factor ('egoism'), which is determined by such motives as 'desire to humiliate, 'need for attention', 'lack of the own point of view'. This complex of motives indicates that the antihero is attributed qualities corresponding to the manifestation of an egoistic tendency. Fromm (1994) characterized such person as follows: 'The egoist is never satisfied. He is always concerned and driven by the fear of not obtaining something, missing something. His envy is strong to anyone who has got more...' (p. 112).

Conclusion

The results of the study showed that the experience of school bullying plays an important role in understanding the motivation of the character's behaviour in key scenes of the film. At the same time, the bullying experience of the viewer is extremely important. Thus, 'setting a scarecrow on fire' (the action symbolizing the 'execution of a traitor') is perceived by 'bullies' as 'hero's desire for leadership', driven by the need to follow the group norms and preserve his social status. 'Victims' also see this act as a "desire for leadership", based on selfish motives and the desire to humiliate others. In this regard, the aggressor's behaviour motivation understanding in bullying situation differs and is based on the previous interaction experience. Interpretation uncertainty reduces, which creates the conditions for the developing of an adequate response based on the previous life experience.

References

Anderson, C. A., Berkowitz, L., Donnerstein, E., Huesmann, L. R., Johnson, J. D., & Linz, D. (2003). The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(3), 81-110. DOI:

Bierman, J. S., Krieger, A. R., & Leifer, M. (2003). Group Cinematherapy as a Treatment Modality for Adolescent Girls. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 21(1), 1–15. DOI:

Dole, S., & McMahan, J. (2005). Using video therapy to help adolescents cope with social and emotional problems. Intervention in School and Clinic, 40(3), 151-155. DOI:

Doumas, D. M., & Midgett, A. (2020). Witnessing cyberbullying and internalizing symptoms among middle school students. European Journal of Investigation in Health. Psychology and Education, 10(4), 957-966. DOI: 10.3390/ejihp e10040068

Elkonin, D. B. (1989). Izbrannye psikhologicheskie trudy [Selected psychological works] Pedagogika.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the Life Cycle. W. W. Norton.

Fromm, E. (1994). Escape from freedom. Holt McDougal.

Khusumadewi, A., & Juliantika, Y. T. (2018). The effectiveness of cinema therapy to improve student empathy. In 2nd International Conference on Education Innovation (ICEI 2018) (pp. 566-569). Atlantis Press. DOI: 10.2991/icei-18.2018 .124

Kulick, A. D., & Rosenberg, H. (2001). Influence of positive and negative film portrayals of drinking on older adolescents’ alcohol outcome expectancies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(7), 1492-1499. DOI:

Marsick, E. (2010). Cinematherapy with preadolescents experiencing parental divorce: A collective case study. The Arts in Psychotherapy 37(4), 311-318. DOI:

Martsinkovskaya, T. D. (2012). Information socialization in changing informational space. Psikhologicheskie issledovaniya, 5(26). http://psystudy.ru/num/2012v5n26/766- martsinkovskaya26.html

Molchanov, S. V. (2016). Psikhologiya podrostkovogo i yunosheskogo vozrasta. [Adolescence and youth psychology], Yurait

Molchanov, S. V., Almazova, O. V., Poskrebysheva, N. N., Voiskounsky, A. E., & Kirsanov, K. A. (2019). Type of cognitive processing of social information and adolescent’s moral judgments. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS (pp. 436-441) DOI: 10.15405/epsbs.2019.07.57

Nabila, S., Nengsih, S. R., & Julius, A. (2021, March). The Use of Cinema to Prevent Cyberbullying. In First International Conference on Science, Technology, Engineering and Industrial Revolution (ICSTEIR 2020) (pp. 209-212). Atlantis Press.DOI:

Podolskiy, O. (2005). Investigating new Ways to Study Adolescent Moral Competence. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 1(4). DOI: 10.5964/ejop.v1i4.380

Rest, J. R., Narvaez, D., Bebeau, M., & Thoma, S. (1999). Postconventional Moral Thinking: A Neo-Kohlbergian Approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sharp, C., Smith, J. V., & Cole, A. (2002). Cinematherapy: Metaphorically promoting therapeutic change. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 15(3), 269-276. DOI:

Sobkin, V. S., & Smyslova, M. M. (2014). Bullying at school: the impact of socio-cultural context (based on cross-cultural research) Social psychology and Society, 5(2), 71–86. DOI:

Soldatova, G. U., & Rasskazova, E. I. (2014). Adolescents’ security in internet: risks, coping and parents mediation. Natsional’nyi psikhologicheskii zhurnal, 3(15), 39–51. DOI:

Stern, S. R. (2005). Messages from teens on the big screen: Smoking, drinking, and drug use in teen-centered films. Journal of Health Communication, 10, 331–346.

Tongsuebsai, K., Sujiva, S., & Lawthong, N. (2015). Development and construct validity of the moral sensitivity scale in Thai Version. Procedia- Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, 718–22. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 December 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-118-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

119

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-819

Subjects

Uncertainty, global challenges, digital transformation, cognitive science

Cite this article as:

Markina, O. S. (2021). Bullying Experience As Factor To Understand Motivation Of Interpersonal Interaction In Adolescence. In E. Bakshutova, V. Dobrova, & Y. Lopukhova (Eds.), Humanity in the Era of Uncertainty, vol 119. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 549-555). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.02.66