Abstract

The object of research in this article is the mechanism of categorization in conditions of uncertainty, i.e. the lack of information about an object or state of things. The research is based on the Russian language material and is carried out using the methods of contextual, component, and oppositional analysis, as well as the techniques of the cognitive matrix method. Using the example of the particular text analysis, the author shows that categorization under uncertainty is implemented as the intersection of the “imperceptible borderline” between non-obvious features of an object of one type and non-obvious features of an object of another type with subsequent verification of the decision made in a specific situation. The linguistic means that formalize this cognitive matrix are: lexical markers of uncertainty; adverbial words with the meaning of the sequence of appearance of different versions; lexical units that name the objects to be categorized. The described mechanism of understanding as “crossing an imperceptible borderline” can contribute to further comprehension of how the choice is made in a situation of uncertainty, what role the external features of objects, the background knowledge of the subject about these objects and, finally, the context of the situation in which the choice is made play in making the decision.

Keywords: Cognitive linguistics, categorization, uncertainty, semantics of the imperceptible

Introduction

The actual problem of modern cognitive science is the question of how a person categorizes objects and situations. In the process of studying the mechanisms of categorization in psychology and linguistics, there is a concept of distinguishing the categories of the basic, higher and lower levels, defining their features and role in the processes of cognition. There is also the concept of the prototypical structure of categories; about the possibility of describing the units of one category using figurative and schematic models of another category (metaphorical models). These include the categorization of the whole through its part and vice versa (metonymic models), the idea of the mental processing during categorization of familiar and unfamiliar objects and the reflection of the results of certain and uncertain categorization in language, etc. These have already been formed (Boyce et al., 1989; Iriskhanova & Prokofyeva, 2020; Lakoff, 2004; Lakoff & Johnson, 2008; Panasenko & Melikhova, 2019; Pinker, 2016; Rosch, 1978, etc.). Nevertheless, when studying the processes of categorization and cognition in general, researchers face more and more new questions. See, for example, the discussion about the nature of knowledge and the linguistic means of its expression in different languages in Mizumoto (2018, 2021) and Farese (2018).

One of the outstanding issues is the question of how categorization is carried out in conditions of uncertainty.

Problem Statement

Categorization under uncertainty involves choosing one of two or more possible options, none of which seems obvious at the time of making a conclusion. In this case, what is the mechanism for choosing one of the alternatives?

Research Questions

In the Cambridge Dictionary, the meaning of the word “uncertainty” is explained as “a situation in which something is unknown, or something is not known or certain” (Cambridge dictionary, 2021). Accordingly, by the term uncertainty, we mean a state of things when the person does not know enough about some objects or phenomena to make a confident choice between the alternatives for categorizing them, and, consequently, to choose the appropriate model of interaction with this object / model of behaviour in this situation. Obviously, in order to be able to make the right conclusions when there is a lack of information about something, it is necessary to achieve the highest possible level of understanding of those features of the object that are currently available for perception, comprehension and interpretation. In conditions of uncertainty, these signs usually do not belong to the typical classifying features of the object (otherwise there would be no problems in categorizing), they are more often weakly expressed, indirect, their perception can be complicated by certain “hindrances” or be too fleeting and contradictory, almost imperceptible. Based on the data of linguistic analysis, we show that under conditions of uncertainty, understanding can be carried out as “following the imperceptible” until the moment when it is necessary to cross a hypothetical verge, dividing two (or more) classes of objects, in order to refer the analysed object to a definite class.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this article is to provide a linguo-cognitive explanation of how the categorization process can be carried out under conditions of uncertainty.

Research Methods

The research is carried out using linguistic methods of contextual analysis, component analysis, oppositional analysis, as well as using a number of techniques of cognitive matrix analysis.

Using the method of contextual analysis, lexical units that characterize the situation of uncertainty are identified. The text must contain at least two types of lexical units listed below:

1) lexical markers of uncertainty – for example, in the Russian language they are the indefinite pronouns [], etc.; conjunctions [], etc.; modal words [], etc.; content words with the general semantics of doubt [], etc.; collocations [], etc.

2) adverbial words and combinations denoting the sequence of making one conclusion first, then another:[], etc.;

3) lexical units, calling the object / situation that can be referred to a certain category (there must be at least two submitted options for a possible categorization).

Using the methods of component and oppositional analysis, we identify semes that associate or differentiate the naming units of objects that should be categorized.

The method of cognitive matrix analysis, proposed by Boldyrev (2019), aims to “identify and bring together in the form of a cognitive matrix various cognitive contexts within which a particular language unit can receive the necessary understanding” (pp. 389-390). The techniques of this method include cognitive matrix modeling and the subsequent “description of the matrix components as a system of cognitive contexts ... underlying the formation of meanings of language units, as well as the means of linguistic actualization of these contexts” (p. 390).

Findings

Let’s turn directly to the question of how the process of categorization is carried out in conditions of uncertainty, i.e. in conditions of a lack of information about an object or situation. The lack of information is not a complete absence of it, but a significant deficit. It means that a person needs to correlate the available facts, information, sensory indications, etc. with the category of objects / situations which are most similar to at the time of making a conclusion on categorization and choosing a model of interaction with this object. Here are some examples (the examples are given in Russian and then in English in the author's translation).

(1) Как болит, в каком месте? Показывает: тут ноет, сюда отдаёт, а здесь как будто подпирает. Поди угадай, что с ней., к животу прямо не относящееся Во всех таких возможностях надо разобраться (И. Грекова. Перелом). [How does it hurt and where? She shows: here it nags, here it shoots up, and here it seems to press. And what's wrong is anyone's guess., not directly related to the stomach,?. It is necessary to understand all such possibilities (I. Grekova. Perelom)].

In this case, we see that the person (the doctor) must make a choice in favour of one of the categorization options (to make a diagnosis: ulcer, appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy, heart attack, or something else) on the basis of non-obvious and overlapping signs, unclear symptoms:[]. The doctor's doubts in a situation of uncertainty are expressed by a whole set of lexical units with the semantics of uncertainty: [].

(2) А справа он… заметил настоящий памятник… но изображавший не человека в полный рост… а только его голову. Но какой большой была эта голова!.. На ум лезли, один из которых лишился в бою головы, и теперь она, залитая в бронзу, украшала собой мраморные холлы этого маленького Содома… Лицо отрубленной головы было печально, и Артём, что она принадлежит из Нового Завета, который ему как-то пришлось листать., что, судя по масштабам, речь идёт, который был большой и сильный, буквально великан, но в итоге всё же оказался обезглавлен. Никто из сновавших вокруг обитателей так и не смог объяснить ему, кому же именно принадлежала отсечённая голова (Д. Глуховский. Метро 2033). [And on the right, he... noticed a real monument… but it wasn't a full-length figure of a man... just his head. But how big that head was!.. His mind was filled with, one of whom had lost his head in a battle, and now this head, encrusted with bronze, was here to adorn the marble halls of this little Sodom... The face of the severed head was sad, and Artyom that it belonged to John the Baptist from the New Testament, which he had once had to leaf through. that, judging by its size, that, who was big and strong, literally a giant, but in the end was finally beheaded. None of the inhabitants scurrying around could tell him who exactly the severed head belonged to (D. Glukhovsky. Metro 2033)].

The above passage describes the “categorization difficulties” of the young man Artyom, who lives in the post-apocalyptic times in the Moscow metro, when most people no longer know or remember anything about their former life and its heroes. The bust of the revolutionary V. Nogin at the metro station “Kitay-Gorod” (formerly “Nogin Square”) in conditions of lack of information and on the basis of only weak signs (“head without a torso”, “sad head”, “huge head”) is identified by the character as a real part of the body of some semi-mythical creature (severed head, giant's head, John the Baptist's head, Goliath's head), but not as a sculptural image of a historical figure. The uncertainty of the person in the correctness of the versions of categorization put forward by him is transmitted with the help of lexical units of [], in the semantics of which there are components ‘inconsistency of reality’, 'suspicion of inconsistency of reality’, ‘uncertainty in full compliance with reality'.

Let's take a closer look at how one of the possible categorization options is selected in conditions of uncertainty.

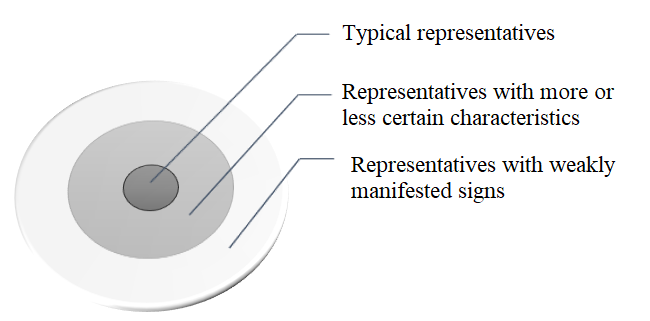

Units of any category, as it is shown in the works of Rosch (1978), differ in how strongly the typical features of the category they belong to are expressed. The structure of a category can be conventionally and simplistically represented as a field with a center and a periphery, where the “best representatives of the category”, i.e. the typical representatives of the category that can be easily and confidently identified, will be located in the very center, and the rest will be located at various distances from the center up to the far periphery, where the representatives of this category with weak and implicit prototypical features are located and which can therefore be taken for the representatives of other categories. On the possibility of grading the features of an object from “typical” to “imperceptible” and the dependence of this process on the knowledge of a particular person, see Kalinina, and Trushkov, (2017). Figure 1 schematically shows the structure of the category.

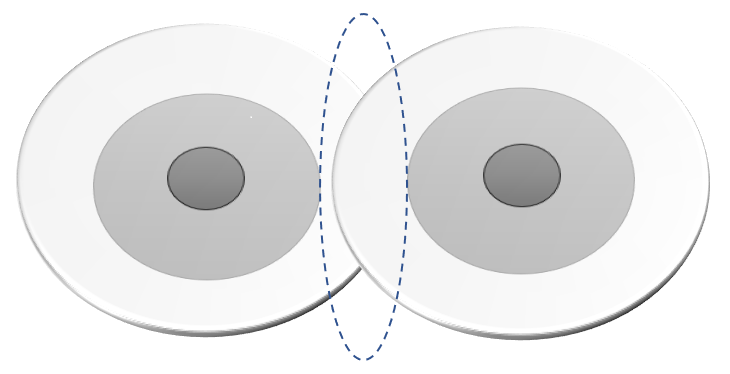

The situation of uncertainty in this case can be represented as the contact, the overlap of two or more categories in the field of weakly expressed, implicit, non-obvious attributes. In Figure 2 the zone of uncertainty is marked with a dotted line: the uncertainty is a transitional, intermediate zone between the categories.

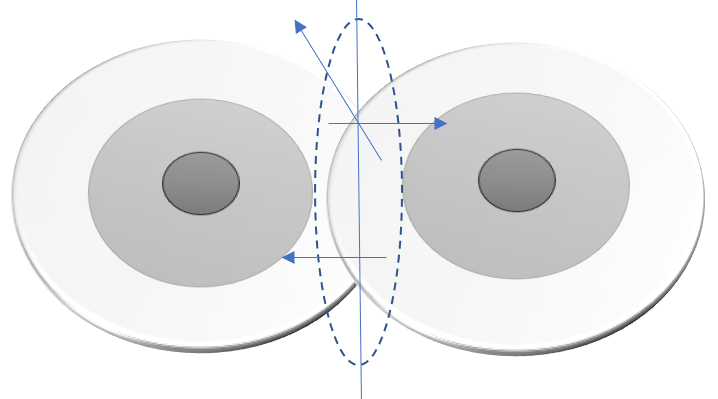

To overcome the situation of uncertainty, a person needs to cross the “imperceptible verge” between weak features that refer to one object and weak features that refer to another object (for the semantics of the “imperceptible verge”, see Kalinina, 2020), and then move towards the expected increase in the prototypical effects of the selected object. If there is no increase in prototypical effects that confirm the correctness of the categorization, then the choice should be reconsidered and the “imperceptible verge” should be crossed in some other direction, perhaps not originally envisaged. See Figure 3.

Let us illustrate how this model works using a certain example. We will consider an excerpt from a fairy tale(1965) by Jan-Olof Ekholm, in which the character, the fox cub Ludwig the Fourteenth, first climbs into a human yard in search of food, sees a scarecrow for the first time, and tries to categorize an unfamiliar object in conditions of lack of information, i.e. in conditions of uncertainty.

(3) Прямо перед ним стоял кто-то высокий. На нём было длинное пальто, а руки раскинуты в стороны. Людвиг Четырнадцатый никогда ещё не видел живого человека, только на картинке в книжке…, этот высокий на клубничном поле и есть?.. На голове у Этого была шляпа, но под ней не было лица с глазами, носом – словом, всем что полагается…, это был. «!» – мелькнуло в голове Людвига… С быстротой молнии он помчался назад (Ян Экхольм. Тутта Карлссон Первая и Единственная, Людвиг Четырнадцатый и другие. Translated from the Swedish by E. Grishchenko and A. Maksimov) [Someone tall was standing right in front of him. He was wearing a long coat, and his arms were outstretched. Ludwig the Fourteenth had never seen a living person before, only in a picture in a book… tall creature in the strawberry field.. The creature had a hat on his head, but under it there was no face with eyes, nose, or anything else that was supposed to be there…flashed through Ludwig's mind… With the speed of lightning, he rushed back.]

Let's analyze this passage. The character (a fox cub, an immature forest animal) meets an unknown object in the territory of a human's residence and tries to categorize this object according to the signs available for perception: []. The main task for the fox cub in this situation is to distinguish a human, as an object that represents an undoubted danger, from a non-human, as an object the degree of danger of which must then be determined specifically. The situation of uncertainty at this stage is formed by the overlap of weak features of the categories “human” and “not a human”, since the fox cub does not know what a human being looks like ( []), or what other potentially dangerous objects can be found in the territory of human residence (due to the infant forest animal’s lack of experience of interaction with a person).

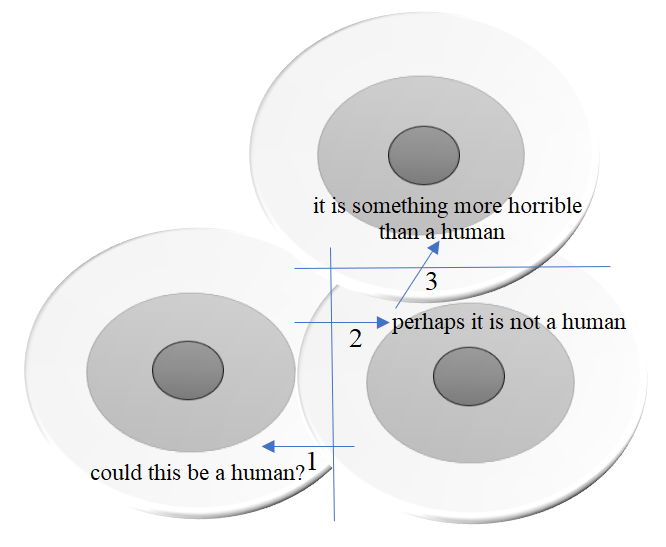

The signs that are available for perception characterize an unfamiliar object as vertical ( []), stationary ( []), having clothes on ( []), having hands that are fixed in a specific way, and not a natural position ( []). Most of the features (tallness, vertical position, presence of clothing, presence of hands fixed in a certain gesture) are suitable for the category “human”, one feature (immobility) can theoretically be suitable for both the category “human” and the category “not a human”. Therefore, the first option of categorization, carried out by the character – []. At this point, the “imperceptible verge” between the categories “human” and “not a human” is crossed, while the character is still “in the zone of uncertainty” (see the speech marker of uncertainty []) and therefore begins to search for stronger signs that could confirm the correctness of the categorization of an unfamiliar object as «» [“]; There is another human attribute among the signs that confirm the correctness of the categorization – [], but immediately there are signs that do not coincide with the existing knowledge about how a human should look: under the hat[]. At the same time, the “imperceptible verge” is crossed in the opposite direction, in favor of choosing the category “not a human”:[] and its particular manifestation:[]. The character is still in a state of uncertainty, as the lexical units [] show. The categorization version that has emerged at this moment ( []) appears as a result of crossing the “imperceptible verge” in the zone of uncertainty between the categories “not human” and “something more horrible than human”. Further verification of the new version is not produced, as the character escapes from a dangerous place “with the speed of lightning”. See Figure 4.

As you can see, in a situation of uncertainty, being able to use only weak signs of a particular class of objects, the character performs three presumptive categorizations one after another, and the third one is a special case of the second one. In each case, the character follows weak, insufficient for confident categorization, non-obvious signs of categories, that is expressed by the use of modal words with the meaning of uncertainty [], and the indefinite pronoun []. However, the character has no other “reference points” of understanding, and he has no other option but to be guided by weak signs in order to be on one side or the other of the thin “imperceptible verge” between the categories. Without crossing this “imperceptible verge”, it is impossible to move towards the center of the selected category and, therefore, it is impossible to verify the choice made.

Conclusion

Categorization in a situation of uncertainty means following the weak signs: first to the imperceptible verge between categories, and then “inward” the selected category until there are more obvious arguments “for” or “against” the conclusion; if there are arguments “against”, you have to follow the non-obvious signs again until the next imperceptible verge with some other category is crossed. The linguistic means that formalize this cognitive matrix are lexical markers of uncertainty; adverbial words with the meaning of the sequence of appearance of different versions; lexical units that name the categories themselves.

The described mechanism of understanding as “following the imperceptible” can contribute to further understanding of how the choice and the conclusion is made in a situation of uncertainty, what role the externally manifested signs of assumed objects, the knowledge already available to the person about these objects, and, finally, the context of the situation in which the choice is made play in making the conclusion.

References

Boldyrev, N. N. (2019). Yazyk i sistema znaniy. Kognitivnaya teoriya yazyka [Language and the System of Knowledge. A Cognitive Theory of Language]. Izdatel'skiy Dom YaSK.

Boyce, S. J., Pollatsek, A., & Rayner, K. (1989). Effect of Background Information on Object Identification. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Perfomance, 15(3), 556-566.

Cambridge Dictionary. (2021). Uncertainty. In Dictionary.cambridge.org dictionary. Retrieved June 11, 2021, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/uncertainty

Farese, G. M. (2018). Is know a semantic universal? Shiru, wakaru and Japanese ethno-epistemology. Language Sciences, 66, 135-150. DOI:

Iriskhanova, O. K., & Prokofyeva, O. N. (2020). Markers of Uncertainty in Speech and Gesture: Some Cognitive Implications for Grice’s Maxims. Voprosy Kognitivnoy Lingvistiki, 4, 18-25. DOI:

Kalinina, L. V. (2020). Semantika neulovimogo: gde prohodit tonkaja gran' [Semantics of Imperceptible: Where the Tonkaja Gran’ Passes]. Voprosy Kognitivnoy Lingvistiki, 2, 114-124.

Kalinina, L. V., & Trushkov, M. A. (2017). «Tipichnoe» i «neulovimoe» kak modusnye kategorii jazyka [“Typical” and “Imperceptible” as Modus Language Category]. Voprosy Kognitivnoy Lingvistiki, 2, 78-89. https://doi.org/

Lakoff, G. (2004). Zhenshchiny, ogon' i opasnye veshchi. Chto kategorii yazyka govoryat nam o myshlenii [Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind]. Yazyki slavyanskoy kul'tury.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2008). Metafory, kotorymi my zhivem. [Metaphors We Live By]. Izdatel'stvo LKI.

Mizumoto, M. (2018). “Know” and Japanese counterparts: “shitte-iru” and “wakatte-iru”. In: Mizumoto, M., Stich, S., McCready, E. (Eds.), Epistemology for the Rest of the World. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Mizumoto, M. (2021). The plurality of KNOW: a response to Farese. Language Sciences, 85, 101369. DOI:

Panasenko, L. A., & Melikhova, D. I. (2019). Subektnyj princip realizacii interpretirujushhego potenciala leksicheskih kategorij (na materiale kategorii «Mlekopitajushhie») [Subject Principle of Realizing the Interpretative Potential of Lexical Categories (Based on the Category of Mammals)]. Voprosy Kognitivnoy Lingvistiki, 4, 77-86. DOI:

Pinker, S. (2016). Substantsiya myshleniya: Yazyk kak okno v chelovecheskuyu prirodu [The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature]. URSS: Knizhnyy dom «LIBROKOM».

Rosch, E. (1978). Principles of Categorization. In Eleanor Rosch & Barbara Lloyd (Eds.), Cognition and Categorization (pp. 27-48). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 December 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-118-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

119

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-819

Subjects

Uncertainty, global challenges, digital transformation, cognitive science

Cite this article as:

Kalinina, L. V. (2021). Categorization Under Uncertainty: On The Verge Of The Imperceptible. In E. Bakshutova, V. Dobrova, & Y. Lopukhova (Eds.), Humanity in the Era of Uncertainty, vol 119. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 464-472). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.02.57