Abstract

The period of entering into profession is the time of intensive competence checkup and young teacher is to decide whether his/her occupation choice was correct or not. Recently, three foremost patterns of interaction between a beginning teacher and his more experienced colleagues have been considered. All the three depend on the style and content of interaction: tutoring, coaching and mentoring. The coach is keen on his young colleagues awareness of the good progress he is making, as well as his responsibility for self-development. In the framework of co-operative research between Yaroslavl State Pedagogical University and University College of Teacher Education in Lower Austria, Austrian colleagues worked out an inquiry form, targeting various mentoring patterns. The survey was accomplished in Yaroslavl region's schools (24 mentors, 62 beginners, 320 students). Results shows the qualities crucial for a mentor: high level of culture and education, friendliness, open-heartedness, diligence, conscientiousness, honesty, and professional competence. Coach is expected to be capable of communicating freely and non-formally. In the process of apprentice-mentor interaction arrangement, not only professional issues should be taken into consideration, but, undoubtedly, also the way each of them evaluates the other’s personality, and the way they both are able to collaborate. Diagnostics showed how young teachers and their mentors perceive certain features of professional interaction (more than 70 features in total).

Keywords: Beginning teachersnovice teachersmentoringcoachingteachers training in Russia

Introduction

The period of entering into profession has a profound impact upon the proficiency development of a specialist. For a beginning teacher, it is the time of intensive competence checkup as well as self-presentation, adaptation, and what's more important, self-determination. Having engaged in teaching, gradually plunging into the profession, getting to know it, he is to decide whether his occupation choice was correct and if he is willing to get involved into education for long. Some beginners in teaching get disappointed with the profession, or rather their capability to deal with it, and have to resign.

The article dwells upon three forms of interaction between a novice teacher and his expert colleague – mentor – to be introduced into practice for the sake of beginner’s easier adaptation and his future career success. The results of the corresponding research are observed, too.

The mentoring tradition in Russia proves to extend over generations. Our research shows that the idea of mentoring, along with the term, was adopted into contemporary Russian education from foreign pedagogics. However, for Russia the idea is not groundbreaking as the mentoring practice in Russian education has come a long way. Batyshev (2005) mentioned that mentoring accompanied an individual throughout all his life, from the cradle of the society, as it transferred the social experience from generation to generation.

Nowadays, due to the promotion of forward-looking institutions of secondary and higher education, along with the position of the Ministry of Education, one can observe mentoring tradition to be getting reinforced in Russian school. Furthermore, mentoring is included into the National Education Project as a separate unit.

Problem Statement

Statistics show that the highest dismissal rate among novice teachers is in the USA: nearly 30% of teachers quit the profession in the primary five years after graduation, in rough areas this amount reach 50%. In Australia the figures come up to 30% (den Brok et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2015; McInerney et al., 2015). According to the data of recent two decades, in Britain about 40% of novice teachers leave their school jobs within first three years of their career (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015; Stoel & Thant, 2002). Regretfully, no current information upon the same issue in the Russian Federation has been found, but the statistics given to the public in 2017 show that almost 33% of teachers give up the career having worked for three years, and 46% within the primary five years of their work (10 facts on Teaching, 2019).

Such figures reveal teacher-training inefficiencies in particular countries, as well as weak points in guiding the inexpert teacher through his first months and years in the profession. The helpful experience of some countries (Singapore, Austria, France, etc.) resulting in only 2-5% specialist outflows in their first teaching years, proves that the stability of beginning teacher’s work is to considerable extent determined by policies of providing students and newcomers in teaching with individual guidance and support for them to develop professionally (Struyven & Vanthournout, 2014; Yinon & Orland-Barak, 2017).

Considering the motives of novice teachers’ outflow from schools, experts seem rather unanimous in their conclusions (Bayborodova et al., 2016; Chernyavskaya & Danilova, 2019; Chernyavskaya, 2012; Hsu et al., 2015; The Teaching Profession, 2015). Notwithstanding the differences in national education systems, these motives prove to be almost the same. They involve professional experience deficiencies, heavy workloads and low salaries, lack of respect on the part of the society, learners’ behaviour, as well as relentless changes in education, external control of teaching, cultural and professional isolation, poor opportunities for career development.

Tutoring is considered the most formal interaction pattern. “Tutorship is didactic assistance to individuals or small groups provided by proficient instructors, peers or other experts” (Beywl & Zierer, 2015, p. 222). The tutor is to detect the problem, select appropriate teaching methods and provide students with individual guidance.

The chief characteristics of tutoring are as follows: equal significance of interaction participants; communication only within the professional field; short-term relationship; scarce targeting at personal development.

Coaching implies a well-structured interaction with the same person throughout a period of time. The coach is keen on his student’s awareness of the good progress he is making, as well as his responsibility for self-development. The features typical of coaching are the following: providing expert guidance in reflection and self-development to enable the student to make decisions and search for alternative strategies; coaching as individual and context-oriented guidance; specific consultancy forms; the trainee sharing the responsibility; coach’s specific role; shared interpretation of the goal; time limit; hierarchy.

Whatever the form, mentoring stipulates for the necessity of interaction within three directions: personal, social, and professional (Choi & Tang, 2009; Ingersoll, 2001).

Being personally guided, an apprentice teacher may count on assistance in case any difficulties occur. The mentor is expected to accept and support the less experienced colleague, boost his self-confidence, and help him handle the situation. These measures contribute into efficient achievement of professional goals as well as enhancing the beginning teacher’s self-assurance and self-belief.

The social direction of novice teacher’s school adaptation considers his promotion into the pedagogical staff and professional unions, so that he felt easier and more comfortable when communicating with his more experienced colleagues, as well as students, their parents, school managers, trustees or inspectors. The professional direction in beginning teacher’s guidance targets at evolving his professional skills, and therefore advancing the competence of the teaching staff and the school’s educational excellence (Kharisova et al., 2018). Thus, we can conclude that it is the mentor’s personality that plays the dominant role in mentoring. For this reason, mentoring can be performed only by an acknowledged expert in teaching, methodology and developmental psychology, who enjoys public esteem and is flexible, outgoing and friendly (Kharisova et al., 2018).

Research Questions

The survey aimed to find answers for the following questions:

1. What type(s) of interaction – tutoring, coaching or mentoring – is the most popular between young teachers and their mentors in Russian schools?

2. What type(s) of interaction prefer (a) young teachers, (b) experienced teachers. Are their preferences match each other or not?

3. What type(s) of interaction are the most preferable by students of Pedagogical University and College – future teachers and are their expectations match the real situation in interaction ay schools?

Comprehending the necessity of assisting novice teachers through their adaptation period led to working out a particular profession-training pattern considering the adaptation period of the beginner, who is already in teaching, to be one of the crucial stages of pedagogical education (Beywl & Zierer, 2015; Chernyavskaya & Danilova, 2019; Dammerer, 2019). The well-known means of such assistance are: engaging beginning teachers in the activities of methodological unions, attending qualified colleagues’ classes, consultations, internal and external training and qualification programs, as well as mentoring. The novice teacher can be guided by either school methodologists or professors of the institution he has graduated from.

Recently, three foremost patterns of interaction between a beginning teacher and his more experienced colleagues have been considered. All the three depend on the style and content of interaction: tutoring, coaching and mentoring (Dammerer, 2019).

In current overseas pedagogical issues, the term “mentoring” is widely used to expose the phenomenon of experienced teacher’s supervision and guidance over an inexpert one. A profound analysis of the terms “mentoring”, “coaching”, and “tutoring” and their interrelation was carried out by a group of Austrian researchers (Dammerer et al., 2019). In accordance with their inferences, tutorship and coaching are regarded as mentoring strategies, tangible and purposeful patterns of guidance mentors apply or stick to.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of research presented was to analyze:

what type(s) of interaction – tutoring, coaching or mentoring - is the most popular between young teachers and their mentors in Russian schools;

are their preferences match each other or not.

Research Methods

Yaroslavl State Pedagogical University (YSPU) closely collaborates with University College of Teacher Education in Lower Austria, where mentor-training and apprenticeship-guidance programs are being carried out (Dammerer, 2019). In the framework of co-operative research project, Austrian colleagues worked out an inquiry form (Chernyavskaya, 2012; Dammerer et al., 2019), targeting at finding out beginning teachers’ and their mentors’ attitude towards various mentoring patterns. In slightly adapted form, the survey was accomplished in a number of Yaroslavl region schools. In total, it embraced 24 mentors, who have been in teaching for more than 15 and up to 37 years, and 62 beginners with 0-2 years of teaching practice in the background.

To find out optimum mentor-apprentice interaction patterns, a questionnaire was offered to 57 YSPU freshmen and senior students and 263 Yaroslavl Pedagogical College students. Out of all the results, in the article suggested we will consider the way students and beginning teachers would like their mentor to be.

Findings

Let us scrutinize a few aspects:

How can I benefit from my profession?

-

It will boost my education level –20%;

-

It will provide me with good salary – 25%;

-

It will enable me to make a career –10%;

-

It will be motivating – 20%;

-

It will reveal my potentialities –20%;

-

I am not going into teaching – 5%.

The responses to this question look encouraging. They could lay the groundwork of personal and social directions in mentoring guidance, as it is reasonable to base upon cognitive interest, teacher’s abilities exposition and extension of education.

Do I need any guidance within my primary years in teaching?

68% of responders answered in the affirmative. Meanwhile, 36% think that the mentor should work for the same educational organization as the apprentice, 15% look at it right the opposite way, and 38% believe he had better work for another profile institution. The rest found the question embarrassing to respond.

The responses show that students are unwilling to limit themselves within the organization they will work for, or even a particular occupation. This is a novel fact to be noted, but it clearly exposes current tendencies of contemporary education. Moreover, the responses disprove the common idea of young people being confident of themselves, and therefore reluctant or critical towards mentoring.

What should the mentor be like?

Responding to the open-ended question in the questionnaire, the college students considered the following options:

personal qualities (light-hearted, cheerful – 3%; caring – 7%; responsive, accepting, supportive – 13%; reliable, responsible – 5%; friendly yet avoiding familiarity – 6%; optimistic – 2%; level-headed – 2%; stress-resistant – 1%; tolerant – 1%; calm – 1%; hard-working – 8%);

education and cultural background (culturally sophisticated – 7%; well-educated – 10%; smart and intelligent – 8%; professionally competent – 7%);

interaction features (persistent – 1%; open-hearted – 5%; punctual – 3%; good at team-work – 3%; honest – 3%).

Responses to the latter question support the afore-stated thesis that it is mentor’s personality that matters the most. The major part of features mentioned refer to the personality, not professional or expert.

Taking the questionnaire results into account, we can enlist the qualities crucial for a mentor. They are as follows: high level of culture and education, friendliness, open-heartedness, diligence, conscientiousness, honesty, and professional competence. Besides, he is expected to be capable of communicating freely and non-formally, which is, probably, the point beginning teachers need and look for.

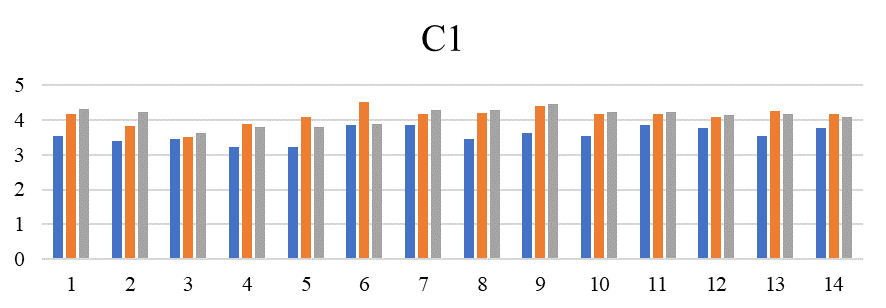

The questionnaire also included a unit upon interaction styles (Figure

The Figure

(1 stands for assistance in professional self-reflection, 2 – discussion of school responsibilities, 3 – assistance in working out an individual teaching style, 4 – assistance in goal-reflection and evaluating the situation, 5 – work upon the command of opportunities and resources, 6 – providing opportunities to make decisions, 7 – support in apprehending and implementing potentialities, 8 – assistance in professional development, 9 – assistance in searching for alternative occupations, 10 – development of self-perception, 11 – contributing into personal responsibility, 12 – stimulation of self-reflection, 13 – consultations upon individual concerns, 14 – consultations upon school teaching process).

The bar chart highlights the points of accordance and disagreement in apprentices’ and mentors’ interpretations. When arranging the interaction, it is essential that both sides should interpret each other’s performance in a similar way.

For instance, let us consider point 6: providing opportunities to make decisions. Apprentice teachers believe their mentors to offer them enough opportunities for decision-making (4, 5 points), whereas the mentors underestimate themselves, assessing this item with a 3, 8 points mark. This result turned out contradictory to the common opinion that beginning teachers have little freedom in their work.

Point 2 – discussion of school responsibilities – discovers an opposing situation: apprentice teachers think that mentors pay too little attention to this issue, while mentors are convinced they do fairly enough.

Conclusion

On the whole, the survey results showed that mentors provide apprentice teachers with sufficient guidance on the part of self-reflection, and contribute effectively to their ability to make professional decisions and put them into practice. All the items of this unit were evaluated by both apprentices and mentors with 3.5 points out of five. More complicated is the situation with mentoring guidance of beginning teachers who work for other educational institutions (infant schools, centres of supplementary education, etc.). They lack experienced colleagues’ consideration and assistance in professional development, goal-reflection and evaluating the situation, as well as in work upon the command of opportunities and resources.

Beginning teacher’s idea of what he might be expected in the profession proves to be rather vague. It takes him several years to build up his own system of life experience, professional knowledge and skills, situation evaluation criteria, choice of appropriate teaching methods, and self-evaluation. In the course of time he will comprehend what teacher’s social role is like and what he is responsible for.

Presently, mentoring as form of beginning teacher’s professional adaptation is being revived and invigorated. In the process of apprentice-mentor interaction arrangement, not only professional issues should be taken into consideration, but, undoubtedly, also the way each of them evaluates the other’s personality, and the way they both are able to collaborate. These are the very issues the article dwelled upon.

References

- 10 facts on Teaching. (2019, January 29). https://rosuchebnik.ru/material/interesnie-fakti-o-professii-uchitel/

- Batyshev, A. (2005). Pedagogical System of Mentoring in Working Staff. Vishaya shkola.

- Bayborodova, L., Chernyavskaya, A., Serebrennikov, L., & Yudin, V. (2016). Project of Individual Learning Activity for Prospective Teachers. 3rd International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts, 1(1), 789-796.

- Beywl, W., & Zierer, K. J. H. (2015). Lernen sichtbar machen. Überarbeitete deutschsprachige Ausgabe von „Visible Learning“ [Making learning visible. Revised German edition of " Visible Learning“]. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren.

- Chernyavskaya, A. (2012). Conditions of Encouraging Students’ Learning. Yaroslavsky Pedagogichesky Vestnik, 2, 313-315.

- Chernyavskaya, A., & Danilova, L. (2019). Mentor’s Role in Beginning Teacher’s Adaptation. Yaroslavsky Pedagogichesky Vestnik, 4(109), 62-70.

- Choi, P., & Tang, S. (2009). Teacher commitment trends: cases of Hong Kong teachers from 1997 to 2007. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 25(5), 767-777.

- Dammerer, J. (2019). Mentoring in der Induktionsphase der PädagogInnenbildung Neu in Österreich / Beitrag zur Internationalen Woche [Mentoring in the induction phase of teacher education new in Austria / contribution to the international week]. Open Online Journal for Research and Education Special, 15, 1-37.

- Dammerer, J., Ziegler, V., & Bartonek, S. (2019). Tutoring and Coaching as Specific Mentoring Forms when Entering the Teaching Profession. Yaroslavsky Pedagogichesky Vestnik, 1(106), 56-69.

- den Brok, P., Wubbels, T., & van Tartwijk, J. W. F. (2017). Exploring beginning teachers’ attrition in the Netherlands. Teachers and Teaching, 23(8), 881-895.

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. (2015). The Teaching Profession in Europe: Practices, Perceptions, and Policies. Eurydice Report. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Hsu, W.-Ch., Chiang, Ch.-H., & Chuang, H.-H. (2015). Factors Affecting Retirement Attitude among Elementary School Teachers. Educational Gerontology, 41(8), 590-603.

- Ingersoll, R. (2001). Teacher Turnover and Teacher Shortages: An Organizational Analysis. American Education Research Journal, 38(3), 501-535.

- Kharisova, I., Bayborodova, L., Cherniavskaia, A., & Khodyrev, A. (2018). Continuous education of teachers in prospective of realization professional standard. 5th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM 2018, 191-198. https://doi.org/10.5593/sgemsocial2018/3.4 /S13.024

- McInerney, D., Ganotice, F., King, R., Morin, A., & Marsh, H. (2015). Teacher's commitment and psychological well-being: Implications of selfbeliefs for teaching in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology. 35(8), 926–945.

- Struyven, K., & Vanthournout, G. (2014). Teachers' exit decisions: An investigation into the reasons why newly qualified teachers fail to enter the teaching profession or why those who do enter do not continue teaching. Teaching and teacher education, 43, 37-45.

- Stoel, C., & Thant, T. -S. (2002). Teachers’ professional lives: A view from nine industrialized countries. Milken Family Foundation.

- Yinon, H., & Orland-Barak, L. (2017). Career stories of Israeli teachers who left teaching: a salutogenic view of teacher attrition. Teachers and Teaching, 23(8), 914-927.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 May 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-107-2

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

108

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1907

Subjects

Culture, communication, history, mediasphere, education, law

Cite this article as:

Chernyavskaya, A., Danilova, L., Golenko, M., & Sal’kova, F. (2021). Patterns Of Interaction Between A Beginning Teacher And His Mentor. In E. V. Toropova, E. F. Zhukova, S. A. Malenko, T. L. Kaminskaya, N. V. Salonikov, V. I. Makarov, A. V. Batulina, M. V. Zvyaglova, O. A. Fikhtner, & A. M. Grinev (Eds.), Man, Society, Communication, vol 108. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1367-1374). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.05.02.174