Abstract

The purpose of the article is to determine the place of Northeast Africa in international relations of the late XIX century. The basis of the work is the principle of historicism, which requires the study of phenomena and processes in connection with the specific conditions that gave rise to them, the identification of both common and peculiar features inherent in these phenomena, the disclosure of objectively existing relationships between facts and their specificity taking into account spatio-temporal relationships. The most significant place in the history of colonial politics was occupied by the Anglo-French rivalry for North-East Africa. It was proved that the most important political initiative undertaken by Paris in relation to London was the attempt to create an Anti-British coalition in 1894–1898. The coalition included France, Russia, Belgium (through the Belgian king as overlord of the Free State of the Congo). Another important pillar of France was to become Ethiopia, having won a landslide victory over the Italian invaders. Attempts have been made to include the Mahdist leadership of Sudan in the coalition. Despite the fact that there was no single agreement between the allies, France had an agreement with each of them that regulated their joint actions regarding the territorial expansion of Great Britain in the Sudanese region. Special attention is paid to Russia's policy in Africa and its cooperation with France. The process of creating an Anti-British coalition, its activities and the causes of defeat in the Fashoda crisis of 1898 is investigated.

Keywords: Africacolonial politicsFranceGreat Britainhistoryinternational relations

Introduction

The nineties of the XIX century were one of the most important periods in the history of international relations. At that time, the foreign policy regrouping of the European powers took place: old alliances collapsed, and new ones appeared in their place.

Main participants

One of the most important components of this process was the relationship between the United Kingdom and France. They were determined primarily by the colonial rivalry of these countries in Africa, where the struggle was fought primarily for Egypt and Sudan. The most important political initiative undertaken by Paris in relation to London was the attempt in 1894-1898 to create an Anti-British coalition. The coalition included France, Russia, Belgium (through the Belgian king as overlord of the Free State of the Congo) and Ethiopia. Attempts have been made to include in its composition even the Mahdist leadership of Sudan. Despite the fact that there was no single agreement between the members of the coalition, France had an agreement with each of them that regulated their joint actions regarding the territorial expansion of Great Britain in the Sudanese region.

Russian position

Of particular interest is Russia's position on this issue. It is traditionally believed that Saint Petersburg did not pay much attention to Africa and did not intervene in the process of colonization of the continent. In fact, during the period under review, Russia played a rather significant role in Northeast Africa, it suffices to say that almost all the borders of Ethiopia and partially Sudan were established by Russian officers who were in active military service. Russia, which had long-standing religious ties with Ethiopia, the only Christian country in Africa, could certainly be useful to its French ally. At the same time, the benefits of developing Russian-Ethiopian relations were obvious. Saint Petersburg would have been given the opportunity to influence the international policies pursued by England, Italy and France in Northeast Africa. There was a project for Russia to acquire a port in the Red Sea, near Ethiopia. It was beneficial for Russia to weaken its old rival, England, and Italy, which it supported, so Saint Petersburg provided all kinds of assistance to France and Ethiopia in the struggle against these states.

Role in international relations

The policies pursued by Great Britain, France, and Russia in Northeast Africa undoubtedly had a strong influence on the regrouping of military-political blocs. Thus, the colonial factor can be considered as part of the problem of the evolution of the international relations of the great powers in Europe.

Problem Statement

The colonial policy of the European powers in Africa at the end of the 19th century is one of the most important components of the history of international relations of this period. Without studying the colonial rivalry of the European powers, it is impossible to understand the processes taking place in Europe, primarily the history of the formation of military-political blocs. The most significant place in the history of colonial politics is occupied by the Anglo-French rivalry for Northeast Africa. The most important countries for the struggle were Egypt and Sudan. In Egypt, rivalry took place primarily for economic control over the country and for the status of the Suez Canal, which was important for the rapid movement of both merchant and military ships from Europe to East Africa and Asia. The Anglo-French rivalry for Egypt was of crucial economic and military strategic importance.

As for Sudan, this country was important for Great Britain and France, because it was a kind of "soft underbelly" of Egypt, having not only a large border with it, but also geographically covering the most important basis of the Egyptian economy - the origins of the Nile. It was the desire to quickly subjugate Sudan that was the reason for both the formation of the Anti-British colonial coalition by France and the intensification of British action in this region after the Italo-Ethiopian war of 1895–1896. In historiography, it is customary to consider the Fashoda crisis of 1898 as a short and largely random episode of Anglo-French rivalry, while both sides had been preparing for it for many years, and the victory of Great Britain in this conflict was not a foregone conclusion at all. France had a much greater chance, with the help of its allies, to be the first to subjugate Sudan and, having made it its colony or even protectorate, dictate to London its conditions regarding Egypt. The radical deterioration of Franco-German relations at the beginning of the 20th century was also not a foregone conclusion, since in the previous decade Paris and Berlin had not only repeatedly reached mutual understanding in colonial matters, but also constituted a united front against British territorial claims. Thus, the activities of the Anti-British coalition in 1894–1898 were of paramount importance for the further development of not only Anglo-French, but also Franco-German relations, only the collapse of the coalition policy made possible the political formation of the Entente.

Research Questions

The author considers it necessary to solve the following research problems:

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the article is to determine the role of Northeast Africa in international relations of the late 19th century, as well as foreign policy, colonial and military problems associated with the formation of an Anti-British coalition in the region, of which France, Russia, Belgium (through the Free State of the Congo) and Ethiopia became members in 1894-1898/1899.

Research Methods

Basic methods

The basis of the work is the principle of historicism, which requires the study of phenomena and processes in connection with the specific conditions that gave rise to them, the identification of both common and peculiar features inherent in these phenomena, the disclosure of objectively existing relationships between facts and their specificity taking into account spatio-temporal relationships. The policy of the main members of the Anti-British coalition in Northeast Africa has been studied taking into account all possible aspects related to their activities: foreign policy, colonial, economic, military, as well as private individuals' initiatives.

Additional methods

General scientific methods were applied: analysis and synthesis (dividing the problem into separate components, followed by their reduction into large picture); induction and deduction (the transition from specific facts to general laws and the application of general laws to specific facts); historical and logical method (the study of historical material in the designated chronological framework based on logical operations); comparison and analogy. The methods of historical research proper are chronological (consideration of events in their sequence); historical-genetic (analysis of the historical background of the studied processes) and historical-comparative. Comparison of the interests of the coalition members in their chronological development made it possible to identify coincidences and discrepancies in their positions on a number of issues, to understand why, ultimately, the coalition crashed and did not achieve its goals.

Findings

Background of the problem

The origins of the future Fashoda crisis of 1898 should be sought back in the early 1880s. The British occupation of Egypt seriously violated French interests in this country. The political situation in Paris was much more unstable than in London. The fear of German aggression in 1882 prevailed over the thirst for new colonial conquests (Tignor, 2010). Moreover, the period of active colonial struggle for Africa did not yet begin. However, a few years later, the situation began to change rapidly: European powers quickly divided African territories. Naturally, in Paris they could not stay away from this process. An important role here was played by economic, military-strategic, cultural and ideological considerations. We should not forget that just at that time the construction of the French colonial empire took place in the Far East. Communication with Indochina was carried out through the Suez Canal, so keeping it in the hands of England became increasingly unprofitable for the French (Vidalenc, 1972). At the same time, as the struggle for Africa escalated, and the Mahdist movement began to threaten to the Cairo, London was less and less willing to ever withdraw British troops from Egypt.

Another important consequence of the capture of Egypt by Britain was the entry of Italy into an alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. The active desire of Rome to acquire new territories in Africa pushed it to search for strong European partners who could help in this. Thus, in our opinion, the Triple Alliance from the very beginning was based on a divergence of interests, since O. von Bismarck needed the forces of Italy in Europe, and not at all for participating in colonial rivalry. Nevertheless, having begun an aggressive policy in the Red Sea region, that is, on the most important trade route, Italy immediately became one of the main players in Northeast Africa to be reckoned with (Zampieri, 2017).

Since the early 1890s, Russia has also become involved in African politics, primarily as an ally of France. The Suez Canal was important for Saint Petersburg as a means of communication with its Far Eastern territories. Moreover, the alliance with France was largely initially directed against England, the old enemy of Russia.

These powers, as well as the African countries Ethiopia and the Free State of the Congo (in fact, the administration of Leopold II) in the 1890s became active participants in the decision of the political fate of Northeast Africa as a whole.

From the beginning of the 1890s, Anglo-French rivalry for Africa entered an active phase. The 1890 agreement only designated the fuzzy spheres of influence of the two states in West Africa, which, moreover, still had to be conquered (Mentan, 2018). Nothing was said in the treaty about Northeast Africa. At the same time, the rest of the continent was colonized. Great Britain began to develop in the territories south of the Mahdist Sudan, and France began to pursue an active policy in Ethiopia. Both Paris and Saint Petersburg did not recognize the establishment of an Italian protectorate over this country (Berhare-Selassie, 2018). It is interesting that Ethiopia, which initially interested Russia directly as a possible bridgehead against England, after the conclusion of the Russian-French alliance began to be considered also as a zone of active interaction between Paris and Saint Petersburg.

The formation of the Anti-British coalition in Northeast Africa

In the first half of the 1890s, most African territories were already captured by various European powers. Only Morocco, the Boer republics, Liberia, Ethiopia and the Mahdist Sudan remained independent. A particularly strong rivalry developed for these countries. Sudan was quickly surrounded by European possessions: British Kenya and Uganda in the south and Egypt in the north, the French zone of influence in the west, the Free State of the Congo under the patronage of the Belgian king in the south. It was Great Britain, France (and Russia allied with it), Ethiopia and Congo that became the main participants in the struggle for Sudan. The French believed that by threatening to undermine the Egyptian water supply, they could weaken the position of the British in this country. The question of whether Paris really intended to build dams on the Nile remains controversial. Technically, this was quite possible, and similar structures were later built by the British themselves, however, in our opinion, the French were hardly going to go that far. They did not intend to conquer Sudan: all the expeditions that intended to send there, and later were sent, were too few in number and could not compete with the Mahdist army. The idea of an alliance with the Caliph Abdallah was not yet discussed, therefore, the interest actively expressed by France in Sudan was a largely propaganda step aimed at changing the position of England on the Egyptian issue (Lyall, 2020).

From 1894 the situation began to change rapidly. Transcontinental colonial projects became increasingly relevant: British (Cape Town – Cairo) and French (Djibouti – Dakar). The Congolese crisis of 1894 showed that Britain could face a hostile coalition. Symptomatic was the temporary rapprochement of Germany and France against England, which corrected their colonial interests in Northeast Africa. It showed that the issue of revenge is not the only dominant of Franco-German relations. The Belgian king Leopold II., who sought to expand the Congo to the north, did not intend to stand aside (Stanard, 2019). The Franco-Belgian agreement was the first cornerstone of an emerging anti-British alliance.

Another important pillar of France was to become Ethiopia, having won a landslide victory over the Italian invaders. The conclusion of the treaty of 1897 on the division of spheres of influence in Sudan became a diplomatic triumph of the French. Ethiopia had extensive experience in wars with the Mahdists and could be used as a military force against them. However, Menelik II, an intelligent and far-sighted politician, sought to play a completely different, completely independent role (Hassen, 2016).

The role of Russia

Of great interest is the identification of the role of Russia in the process of forming new borders in Northeast Africa. If we talk about the ongoing controversy regarding Russian colonialism and the applicability or inapplicability to the policy of Russia in Africa of the concept of orientalism by E. Said, arguing that an integral part of colonialism was the desire to attach the "primitive" Eastern peoples to Western values, then the author believes that this concept may be applied to Great Britain and France, but not to Russia (Ganguly, 2015). Saint Petersburg policy in Africa was associated with two main aspects. Firstly, the desire to prevent the capture of the Suez Canal by Great Britain, since the canal was important for Russia as a means of communication with its Far Eastern territories. Secondly, Russian policy in the region was determined by the alliance with France, which was largely initially directed against England, the old enemy of Russia. At the same time, the documents of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs have repeatedly emphasized the absence of any aggressive plans in Africa in Russia. The private initiatives of Nikolai Leontyev related to attracting Russia to the economic exploitation of certain Ethiopian territories did not find understanding in Saint Petersburg. It is proved that the Ministry of Finance categorically objected to Russia's active policy in Africa, while the War Department also emphasized the need for extreme caution and restraint in this area. Some Russian officers who participated in Ethiopian military expeditions received a very cool welcome in their homeland. Thus, it can be stated that Russia in no way can be considered a contender for participation in the process of colonial partition of Africa (Morozov, 2010).

Interests of participants

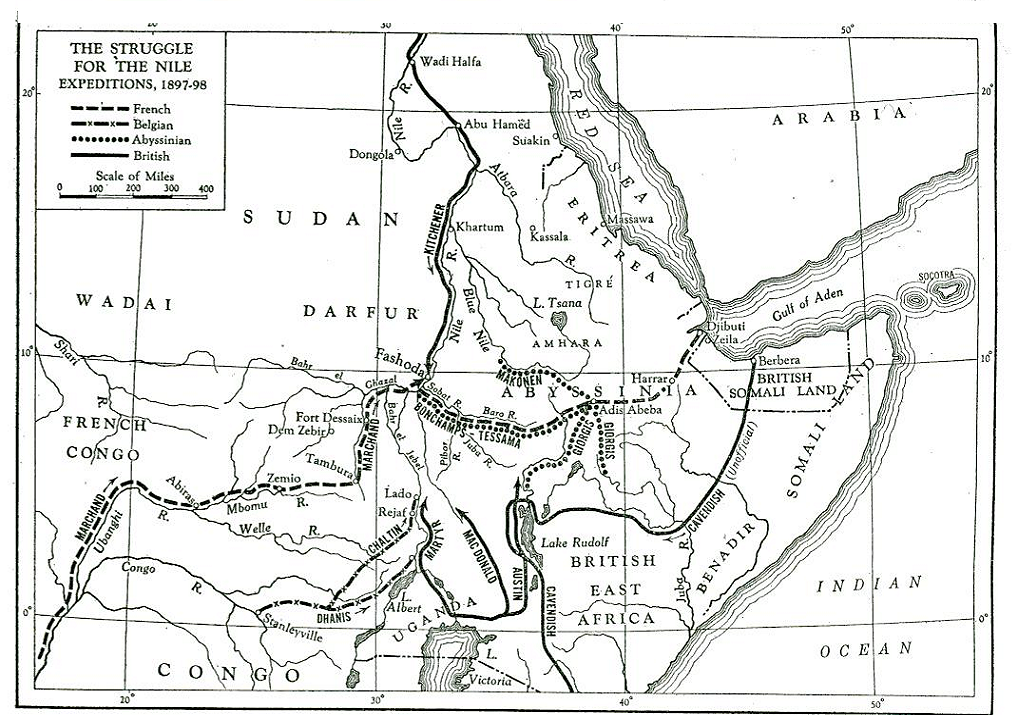

In 1897, the final formation of the Anti-British coalition took place, of which France (with the support of Russia), Belgium (through the Free State of the Congo), Ethiopia and, to some extent, even the Mahdist Sudan became members (Figure

The only solution that could suit all members of the Anti-British coalition was the transition of Sudan to a French protectorate with the preservation of the Mahdist administration. Khalif Abdallah was a realist and often used Europeans to his advantage, did not exclude such an opportunity. The only alternative was the death of the state and the annexation of it by England. Expedition of J.-B. Marchand moved to Sudan from the southwest, Ethiopian troops with the support of French and Russian advisers advanced from the east (Parry, 1956).

Conclusion

The situation in Northeast Africa, which developed in 1897 so favorably, sharply worsened in 1898. Although the Anglo-German agreement on dividing the Portuguese colonies into spheres of influence was only a tactical move on the part of London to force Germany to abandon the possible support of France in Northeast Africa, as happened in 1894, this agreement nevertheless reached its goal (Copeland, 2015). French and Ethiopian expeditions failed to reach Sudan from the east, and Belgian expeditions from the south. In France itself, the crisis connected with the Dreyfus affair worsened. In addition, the Russian envoy in Addis Ababa, P. Vlasov, sought to play a leading role in the court of Menelik, even to the detriment of relations with the French envoy L. Lagarde, while in Saint Petersburg Ethiopia was seen only as an auxiliary Russian-French front against England. Although Russian officers participated in all of Menelik’s military expeditions, the attempt to create a Franco-Russian-Ethiopian alliance failed. During the Fashoda crisis, the French government did not seek help from its Russian ally, since it was not interested in a war with England over Sudan. France did not hide that it was only seeking the convocation of an international conference on the Egyptian issue, and from the very beginning of the negotiations it took a defensive position (Oosterveld et al., 2015). The new Minister of Foreign Affairs, T. Delcassé, who was much more pro-English than his predecessor G. Hanotaux, always considered Berlin a more dangerous opponent than London, and wanted to come to terms with Great Britain. It was Hanotaux, and not Delcassé, who was the chief architect of the Anti-British coalition, and, naturally, that after his resignation, it began to disintegrate (Rose, 2019). The Russo-French negotiations on joint actions against England that followed during the Boer War led to the conclusion of a number of informal agreements, but such measures as the landing in England and the Russian attack on India were difficult to implement. The hope of radical interference in Egyptian affairs disappeared, a psychological shift occurred, and in this sense the final settlement of the Anglo-French rivalry was approached. Ethiopia also did not take advantage of British difficulties in southern Africa to regain eastern Sudan, as it was not ready for war. All these factors later led to a warming of Anglo-French relations and to the Entente of 1904.

References

- Berhare-Selassie, T. (2018). Ethiopian Warriorhood: Defence, Land and Society 1800–1941. Rochester, James Currey.

- Copeland, D. C. (2015). Economic Interdependence and War. Princeton University Press.

- Ganguly, K. (2015). Revisiting Edward Said's Orientalism. History of the Present, 5(1), 65-82.

- Hassen, A. (2016). Revisiting Emperor Menelik: A Historical Essay in Reinterpretation, ca.1855–1906. Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 49, 79-97.

- Lyall, J. (2020). Divided Armies: Inequality and Battlefield Performance in Modern War. Princeton University Press.

- Marcus, H. G. (1966). The Foreign Policy of the Emperor Menelik. 1896–1898: A Rejoinder. Journal of African History, VII(1), 117–122.

- Mentan, T. (2018). Africa in the Colonial Ages of Empire: Slavery, Capitalism, Racism, Colonialism, Decolonization. Langaa RPCIG.

- Morozov, E. V. (2010). Russia, relations with. In S. Uhling (Ed.), Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Vol. IV (pp. 417-421). Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Oosterveld, W., De Spiegeleire, S., & Sweijs, T. (2015). Pushing the Boundaries: Territorial Conflict in Today’s World. Hague Centre for Strategic Studies.

- Parry, A. (1956). Africa: Not So New for the Russians. The Georgia Review, 10(2), 142–149.

- Rose, A. (2019). Between Empire and Continent: British Foreign Policy before the First World War. Vol. 5. Berghahn Books

- Stanard, M. G. (2019). The Leopard, the Lion, and the Cock: Colonial Memories and Monuments in Belgium. Leuven University Press.

- Tignor, R. L. (2010). Egypt: A Short History. Princeton University Press.

- Vidalenc, J. (1972). Le Canal de Suez dans l'histoire (1854–1956). Revue d'histoire économique et sociale, 50(1), 132–134

- Zampieri, F. (2017). The Sea in History – The Modern World. Suffolk, Boydell & Brewer, Boydell Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 May 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-107-2

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

108

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1907

Subjects

Culture, communication, history, mediasphere, education, law

Cite this article as:

Morozov, E. (2021). Northeast Africa In International Relations Of The Late 19th Century. In E. V. Toropova, E. F. Zhukova, S. A. Malenko, T. L. Kaminskaya, N. V. Salonikov, V. I. Makarov, A. V. Batulina, M. V. Zvyaglova, O. A. Fikhtner, & A. M. Grinev (Eds.), Man, Society, Communication, vol 108. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 893-900). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.05.02.114