Abstract

In today's context, sustainable behavior patterns are subject to alter in response to rapidly changing economic conditions. The behavior of corporate enterprise actors can be transformed into an opportunistic one. The focus on short-term prospects results in a breach of informal and formal terms and conditions of agreements with intent to increase personal benefits. According to the economic theories, opportunism is traditionally defined as a type of self-seeking behavior of an individual. Such behavior is typical of all economic agents and can be exhibited to varying degrees. The emergence of opportunism is considerably increased (including those actors who are not prone to it) if specific sustainable behavior patterns promote and encourage opportunistic behavior. Any collective work gives rise to the elimination of individual accountability for the end result, which leads to employees' demotivation and decreased performance. Each corporate actor's opportunistic behavior entails costs; however, the losses caused by collective opportunism are much more significant. The studies related to the conditions for such behavior can help develop effective measures to prevent it and to reduce the associated costs to a great extent. This article illustrates the conditions that can deter and foster possible collective opportunistic behavior at the corporate enterprise. There were identified three groups of factors that have a significant impact on establishing such conditions.

Keywords:

Introduction

The mechanisms aimed at enhancing interaction between individuals in groups, i.e. their cooperation, have been developed within several decades. In many cases, group interests contradict individual ones, and the behavior aimed at personal benefits and its motives are a subject matter of economical, psychological, and sociological studies. The interdisciplinary nature of opportunism studies results in various definitions for this term in modern science (Pletnev & Kozlova, 2020a). Alternative approaches to the analysis of behavioral prerequisites provide a shared vision that social and psychological factors have a major impact on behavior. New institutional economics describes human nature in the context of bounded rationality and opportunism. Williamson (1985) defines opportunism as a worst-case pattern of self-seeking behavior. All individuals tend to exhibit opportunistic behaviors, but to varying degrees, which results in additional costs associated with defense and the degree of opportunism manifestation in interactions. Morals and legal regulations restrain the pursuit of personal gains, i.e., some restrictions can prevent opportunistic behaviors. Growing opportunism leads to distrust between people, which significantly impairs effective interactions and increases the costs. The social relations between people are based on previous interactions' experience evolved in response to acts of individuals in the team. If the previous experience is regarded as successful, it is possible to deter opportunistic behaviors due to trust level (Raub et al., 2019). It is particularly noteworthy that an individual exhibits its opportunistic behaviors to varying degrees in different environments.

Among the diverse opportunistic patterns common for any corporate enterprise, much focus is made to the opportunism of managers (Ali & Hirshleifer, 2017; Ghouma, 2017; Ntim et al., 2019), opportunistic behaviors of freelancers (Shevchuk & Strebkov, 2018), the theft of innovative ideas by employees (Pandher et al., 2017), as well as opportunism in intercompany relations (Chai et al., 2019; Huo et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2018). The methods used to evaluate and measure opportunistic behaviors at corporate enterprises for labor relations are discussed in detail in Popov and Ersh (2016); Pletnev and Kozlova (2020b). Lumineau and Oliveira (2019) carried out the detailed analysis of empirical studies of opportunism and proposed some solutions to improve the existing methods used to measure opportunism.

Problem Statement

In most cases, opportunism is defined as a characteristic of an individual economic agent, interactions are described from the perspective of two actors solely, but collective actions remain insufficiently explored. The opportunistic group behavior is defined as the aggregate degree of opportunism of each actor. At the same time, the fact that internal group processes result in transformations, strong relations, interpersonal trust and coordination is paid no attention. However, at least one group member's opportunistic behavior can have a significant impact on the acts of others. Interpersonal trust is an important factor for successful cooperation, which can be greatly impaired due to the actors' opportunistic behaviors. Maximum personal gains at the expense of other people are not always the most realistic human behavior model. Largely, individuals' behavioral patterns are shaped under family values and those acquired in the socialization process, determined by the previous experience, and are considerably dependent on specific circumstances. While interacting with different people and under various circumstances, the same person can have different attitudes to a breach of agreement, considering it either appropriate or unacceptable.

Differing interests of an employee and an employer make each of them seek maximum benefits while avoiding the agreement for as long as possible. The low corporate culture at the enterprise leads to mass opportunistic behaviors. However, not all members of the social group tend to be equally opportunistic. The assessment of collective opportunism makes it possible to determine the conditions contributing to its emergence and manifestation.

Research Questions

What conditions contribute to forming collective opportunism patterns at the corporate enterprise?

Purpose of the Study

This study aims to determine the conditions for collective opportunism at the corporate enterprise.

Research Methods

Stelder (2015) defines collective opportunism as "the conscious behavior of collaboration as a whole to act according to a common conflicting interest for that collaboration's overarching goal" (p. 10). According to Stelder, this behavior is based on a shared interest (being the basis for individuals' cooperation) and a gradually evolving conflicting one. If all interacting actors share the same conflicting interest, this can give rise to collective opportunism and prevent them from achieving the primary objective, i.e. team building. The problem of collective opportunism cannot be addressed through initial stringent staff selection, as it arises in the process of interaction and is encouraged by the majority of its actors. To address the problem of collective opportunism, two preconditions must be met. Firstly, each actor shall have the need to tackle the problem, and secondly, everyone shall be aware that the problem can be addressed only through cooperation and joint efforts. In other words, all actors shall be convinced that their problem will be eliminated through cooperation.

We would like to call attention to the Mazar et al. (2008) experiment, one of the most famous works covering different degrees of opportunism of individuals developed due to the social environment. Minor changes in the initial experimental conditions resulted in significant changes in the opportunism degree of the subjects. Among the factors contributing much to opportunistic behaviors, one can distinguish the lack of performance monitoring, the trust-based remuneration paid, and individuals characterized by a high degree of opportunism being members of the group. The significant experiment results also demonstrate that most actors did not exhibit the maximum degree of opportunism, despite real opportunities to do so.

In other words, an individual does not always try to get maximum benefits if it involves fraud. This fact is also referred to by the experiment initiators, who suggest that morals and the code of conduct applicable in the group have a considerable impact on the individual’s behavior. It is particularly relevant for corporate enterprises, where long-term communications and a great number of contacts between the members while performing their work duties result in the emergence of sustainable informal behavior norms in the team.

To reduce losses due to employees' opportunism, Vafaï (2010) corporation suggests using the "principal – supervisor – agent" scheme. When providing any information to the principal on the agent's performance through the supervisor, there is an issue of the "control over the supervisor," and the parties may choose several possible behavior patterns. When the supervisor implements the agreements in full and provides detailed information on the agent's low performance to the principal, i.e. does not behave opportunistically, the principal's losses are reduced to a minimum. If the supervisor conspires with the agent and agrees to conceal information on the agent's low performance for a certain fee, the principal's losses increase to a great extent (supervisor-agent collusion). If conspired with the principal, the supervisor can provide for an additional fee (by reducing the agent's salary) reliable information on the agent's performance (abuse of power). The author concludes that if the agent demonstrates high performance, there is no need for the supervisor to enter into a coalition with him. This is equally relevant for the fees, in case the remuneration provided by the principal is not less than the one offered by the agent.

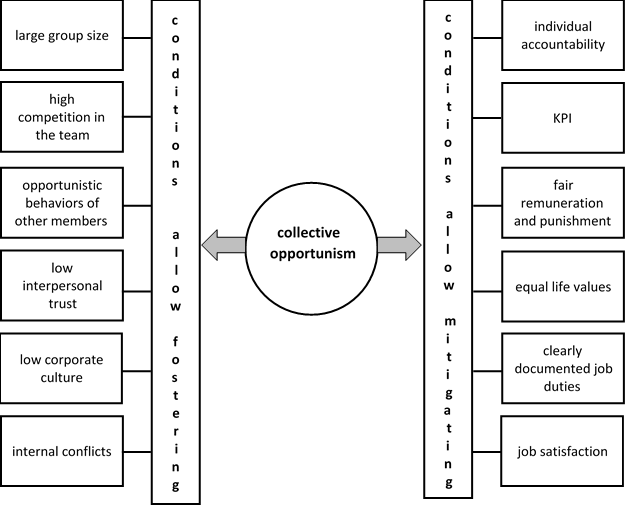

The experiments demonstrate that one cannot neglect the impact of other team members on an individual's behavior, particularly his opportunism. Among the significant prerequisites contributing to collective opportunism, one can distinguish the following factors: personal and psychological factors (internal morals determining the behavior, willingness to cooperate with other members, susceptibility to the influence of other people, job satisfaction, strong motivation), social factors (general willingness to behave opportunistically in the team, individuals exhibiting opportunistic behaviors in the group, low corporate culture, high competition, different values of group members, intra-group conflicts) and legal provisions (performance monitoring systems, allowing for calculating remunerations, the system of penalties, clearly documented job duties for each employee).

Of the factors listed above, personal and psychological factors may be least affected. To create the conditions allowing for strong motivation and job satisfaction of each employee is rather challenging. Opportunism may be considerably mitigated in the teams in which employees are enthusiastic about their work. In case of low motivation among employees and inactivity during working hours without losing the fixed salary, the overall degree of opportunism will be relatively high (at least in terms of shirking). Susceptibility of an individual to the influence of other people, his willingness and desire to cooperate with colleagues, and morals determining the behavior are personal characteristics shaped in the course of education and previous life experience. Equal life values and the conditions for favorable interaction with colleagues allow mitigating motives for self-seeking behavior.

To deter opportunism at corporate enterprises, the appropriate focus shall be made on the legal regulation of labor relations at the local level. All employees shall be informed and well aware of the documents stipulating the rules and the procedure for payroll accounting, assessing the performance of subdivisions, departments and each employee individually, and providing with the list of job duties. Job motivation and loyalty to the company are significantly increased among employees, in case they do not object to the current bonus and penalty systems. As far as the group work is concerned, when the final work results are impersonal, it is easier to cover up a failure to fulfill one's duties or unwillingness to do one's best than in case each employee has an individual task. Individual accountability for work performance provides for penalties regarding opportunistic behaviors. The penalty amount shall be rather substantial, only then all team members will benefit from performing their duties in good faith. In other words, a cooperation actor tends to be less opportunistic if his benefits are significantly smaller if he violates the agreement terms rather than when he implements them. Penalty-free opportunistic behaviors result in not only costs, but also low interpersonal trust in the team. Simultaneously, opportunism is mitigated if every individual is confident that all team members act in good faith. No clear performance indicators for employees' group and individual work result in low motivation and decreased workforce productivity. The performance monitoring system does not ensure the elimination of employees' opportunistic behaviors; however allow mitigating the degree of opportunism to a great extent. In such a system, objective and subjective performance indicators shall be balanced. Moreover, not only separate indicators but also the overall performance of an employee shall be assessed. Significant differences in some indicators' values can make employees focus their efforts on certain indicators and completely neglect others. If the work performance is difficult to measure in terms of quantity, the individual tends to overestimate the efforts undertaken and the work complexity, especially in case of inability to verify this information. To mitigate opportunism, remunerations shall be fairly distributed, proportionate to the undertaken efforts.

Social factors arise from personal and psychological factors as well as legal ones. Opportunistic behavior patterns may emerge at the corporate enterprise more often if other team members resort to such behavior. If the team is highly competitive, an individual may violate the rules to hold a winning position or gain advantages. No legal mechanisms to mitigate opportunistic behaviors as well low morals of employees make them behave opportunistic even if they are not initially prone to such behaviors. Fragile corporate culture and intra-group conflicts result in fostering collective opportunism.

Findings

Following the analysis of factors having its impact on the conditions contributing to collective opportunism, one should identify those that allow fostering and deterring opportunistic behaviors (Figure

Internal factors and external conditions have a major impact on the decision-making and behavior patterns of any individual. Self-seeking behavior and personal interests of an employee may contradict the interests of the team or the employer. Individuals being members of the group tend to behave opportunistically to varying degrees. Favorable conditions for collective opportunism make employees (all or most of them) give priority to personal interests rather than those of the corporate enterprise. Difficulties of eliminating and identifying collective opportunistic behavior are associated with the hidden nature of such behavior and its mass character. In the long run, collective opportunism leads to decreased operation performance rates, low competitiveness, and human capital loss.

Conclusion

The corporate enterprise's growth shall definitely entail the growing complexity of its structure and increased number of its members. Bringing together a large number of people to address shared problems is rather difficult, as each individual seeks, above all, to satisfy his or her self-interest. The larger the group is, the more likely individuals are exhibiting opportunistic behaviors in such a group. At the same time, the level of interpersonal trust decreases as the number of group members grows. In other words, one can assume that there is a direct correlation between the growth of the group size and the emergence of opportunistic behaviors among its members. In this case, the problem can be eliminated in part by dividing the department into smaller groups to fulfill minor tasks towards a common goal.

The problem of collective opportunism is much more complex than that of the opportunistic behaviors of any individual. In case of failure to actually mitigate opportunistic behaviors exhibited by one of the employees, in the worst-case scenario, he can be fired. If opportunism is a collective problem, it can be tackled exclusively in a comprehensive manner by eliminating the conditions for its formation and emergence. The analysis of the factors having a major impact on collective opportunism allows for monitoring to discourage such behavior.

Acknowledgments

The reported study was funded by RFBR, project number 20-010-00653

References

- Ali, U., & Hirshleifer, D. (2017). Opportunism as a firm and managerial trait: Predicting insider trading profits and misconduct. Journal of Financial Economics, 126(3), 490-515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.09.002

- Chai, L., Li, J., Clauss, T., & Tangpong, C. (2019). The influences of interdependence, opportunism and technology uncertainty on interfirm coopetition. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 34(5), 948-964. https://doi.org/10.1108/jbim-07-2018-0208

- Ghouma, H. (2017). How does managerial opportunism affect the cost of debt financing? Research in International Business and Finance, 39, 13-29.

- Huo, B., Tian, M., Tian, Y., & Zhang, Q. (2019). The dilemma of inter-organizational relationships Dependence, use of power and their impacts on opportunism International. Journal of Operations & Production Management 39(1), 2-23. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-07-2017-0383

- Lumineau, F., & Oliveira, N. (2019). Reinvigorating the Study of Opportunism in Supply Chain Management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 56(1), 73-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12215

- Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The Dishonesty of Honest People: A Theory of Self-Concept Maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633-644. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.45.6.633

- Ntim, C., Lindop, S., Thomas, D., Abdou, H., & Opong, K. (2019). Executive pay and performance: The moderating effect of CEO power and governance structure. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(6), 921-963. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1282532

- Pandher, G. S., Mutlu, G., & Samnani, A.‐K. (2017). Employee‐based Innovation in Organizations: Overcoming Strategic Risks from Opportunism and Governance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 11, 464-482.

- Pletnev, D., & Kozlova, E. (2020a). Context Of The Term “Opportunism” In Economic Science. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences EpSBS: 10th International Conference “Word, Utterance, Text: Cognitive, Pragmatic and Cultural Aspects, 86, 635-643.

- Pletnev, D., & Kozlova, E. (2020b). Methodology for assessing worker’s behavioral opportunism in Russian corporations. Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings; Varazdin, 426-434.

- Popov, E., & Ersh, E. (2016). Institutions for Decreasing of Employee Opportunism. Montenegrin Journal of Economics, 12(2), 131-146.

- Raub, W., Buskens, V., & Frey, V. (2019). Strategic tie formation for long-term exchange relations. Rationality and Society, 31(4), 490-510.

- Shevchuk, A., & Strebkov, D. (2018). Safeguards against Opportunism in Freelance Contracting on the Internet. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 56(2), 342-369.

- Stelder, V. (2015). The hazard of collective opportunistic behavior: The inability of hybrid modes of governance to cope with an adverse incentive in the Dutch office market. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-hazard-of-collective-opportunistic-behavior%3A-of-Stelder/8a7e10582d6624e88e648e851f0aeefb681d1621

- Vafaï, K. (2010). Opportunism in Organizations. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 26(1), 158–181.

- Williamson, O. E. (1985). Behavioral Assumptions. In O.E.Williamson. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting. (pp.44–52). N.Y.: The Free Press.

- Yang, D., Sheng, S., Wu, S., & Zhou, K. (2018). Suppressing partner opportunism in emerging markets: Contextualizing institutional forces in supply chain management. Journal of Business Research, 90, 1-13. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 April 2021

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-104-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

105

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1250

Subjects

Sustainable Development, Socio-Economic Systems, Competitiveness, Economy of Region, Human Development

Cite this article as:

Kozlova, E. (2021). Prerequisites For Collective Opportunism At Corporate Enterprises. In E. Popov, V. Barkhatov, V. D. Pham, & D. Pletnev (Eds.), Competitiveness and the Development of Socio-Economic Systems, vol 105. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 365-372). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.04.40