Abstract

In the article, the authors analyze the token“Heimat” / “homeland” in modern German. To achieve the set goal, the authors compare the data obtained in a free associative experiment with the contexts of using the word in real Internet communication. The free associative experiment was conducted with members of German linguistic culture in April, 2019 in the area of Fechte, Potsdam, Berlin, Baden-Baden, Freiburg. Both in the associative experiment and in the Internet communication, the psychologically real meaning of the lexeme is actualized, so the collected data were comparable. The core of the concept is the semantic attribute “territory (country, city, place)”, which also includes the image of the road / way home, as well as the meaning “place of origin of a living being or an object”. These semantic features are also reflected in the vocabulary definition of the lexeme, which indicates their fundamental nature. A distinctive feature of the semantic and associative fields is the attribute of family. The verbal reaction “family” has a deeply personal meaning among respondents, though may find no verbal expression in Internet communication. We believe that due to the fact that in a free associative experiment no restrictions are placed on the nature and number of reactions, this makes it possible to identify real functioning meanings that may not be actualized in other types of communication.

Keywords: Associative experimentconceptnominative fieldsemanticscore

Introduction

At the moment, the assertion that the participants of communication interact not through separate lexical units, but with the help of more complex functional formations (coherent phrases and texts) seems indisputable. The word captures the meanings in human consciousness, from which it follows that a deep versatile analysis of the semantics of the word reveals the whole range of cognitive meanings that arise in the psyche of communicants when generating or perceiving a text (Daulet et al., 2019; Normurodova & Sirojiddinov, 2019).

The content of the concept is presented in the minds of native speakers; however, it is not always encoded in a dictionary (Gawda, 2019). To determine the content of the concepts under consideration, an analysis of the contexts of their use is necessary.

Problem Statement

According to Pishchalnikova (2019) specifically “an associative experiment reveals the person’s activity attitude to the world, represented by linguistic means, which determines the strategies of verbal activity that are relevant for the individual and indirectly – the specifics of the conceptualization of the world” (p. 758). “If earlier an associative experiment was used in linguistic research to model static semantic structures, then in modern linguistics, by solving linguistic-cognitive, linguoculturological and psycholinguistic tasks based on the interpretation of associative fields, scientists have discovered the internal plasticity of associates” (Khlopova, 2018b, p. 83). Thus, associative-verbal networks contain, along with lexical and grammatical information, a cognitive and pragmatic component, linguistic specificity and features of the linguistic picture of the world of a native speaker of the concerned language.

A significant number of works in various fields of science are devoted to the analysis of the concept “Heimat” (Ashkenazi, 2012; Bätzing, 1991; Hornstein Tomić, 2011; Schiller, 2018; Sieberer & Machleidt, 2015), but they do not cover the whole variety of meanings inherent in the presented concept.

Research Questions

To achieve the above goal, a number of tasks are to be solved: 1) to reveal semantic groups of the meaning of the word “Heimat” recorded in various lexicographic sources; 2) to compare the obtained results with the text analysis of internet publications; 3) check the conclusions obtained in the course of the analysis on the basis of the conducted associative experiment.

Purpose of the Study

The choice of the concept Heimat / homeland for this study is due to the complex nature of the concept itself, which contains a specific geographical and political significance (country, city), as well as the need for security, belonging and identity (Peterlini, 2010; Jacobson, 2003; Sieberer & Machleidt, 2015). The study of this particular concept seems to us especially relevant in view of the fact that “Heimat” (“homeland”) is the basic value, respectively, the lexeme is frequency both in the speech of native speakers and in Internet communication. The study of the content of value by analyzing the token itself seems logical, since “only with the help of language do values become a part of the personality’s consciousness, determining its activity and behavior” (Bubnova, 2019, p. 94).

The purpose of the study is to identify the actual meaning of the Heimat token (“homeland”) by comparing the data of definition dictionaries and an associative experiment with contexts from real Internet communication through the social network Twitter.

Research Methods

The study material was composed of the contexts of the use of lexical units included in the core nominative field of the Heimat concept, taken from the German-language contexts of the Heimat token use on the twitter social network, as well as the results of a free associative experiment conducted in April, 2019 with German language culture representative from 17 to 23 years old.

The methodological basis of the study was the theory of cognitive linguistics, in particular, the phenomenon under consideration is understood by us as a concept, that is, a “discrete mental formation, which is the basic unit of a person’s mental code, has a relatively ordered internal structure, which is the result of cognitive activity of a person and society and carrying complex, encyclopedic information about the reflected subject or phenomenon, about the interpretation of this information by public consciousness and the attitude of public consciousness to a given phenomenon or object” (Popova & Sternin, 2007, p. 24).

The leading method of analysis was the semantic-cognitive analysis of the language (Popova & Sternin, 2007; Shaposhnikova, 2018; Balandina & Peredrienko, 2019). This method involves the sequential implementation of the analysis steps, including not only the analysis of the semantics of the units belonging to the concept nominative field and the contexts of their use, but also verification of the results using an associative experiment.

Findings

Heimat concept’s nominative field

To begin with, the nominative field of the Heimat concept as a set of synonyms objectifying it in the language was revealed on the basis of dictionaries. By applying the obtained data and context analysis, peripheral features of units included in the nominative field were revealed. A generalization and comparison of the results allows us to conclude about the existing peripheral and evaluation meaning components of the concept in question.

In the nominative field of the Heimat concept, there are two semantic groups represented by synonyous lexical units (Hereinafter, our translation. – O. L., A. Kh.): 1) Geburtsland / country of birth; Heimatland / homeland; Vaterland / fatherland (associated with Heimatforscher / homeland researcher; Heimatkundler / local history expert; heim / home; heimwärts / homeward; nach Hause / back home; nachhause / back home), 2) Hauptstätte / main site; Hochburg / citadel; Mekka / Mecca; Hauptstadt / capital (associations: Ausgangspunkt / starting point; Ursprungsort / place of origin; Wiege (geh., Fig.) / cradle; Eldorado (für) / Eldorado; Traumziel / dream destination; Wunschland / dream country; (das) Mekka (der) / Mecca; floskelhaft / yeasty; El Dorado (spanisch) / El Dorado; Land wo Milch und Honig fließen (Redensart fig.) / a land of milk and honey; Arkadien (des / der …) / Arcadia (https://www.dwds.de/wb/Heimat).

The investigated dictionary definitions allow us to identify the following cognitive characteristics of the Heimat token: 1) a specific territory (country, city, place); 2) the emotional connection of a person with this place, the subjective feeling of "home"; 3) the place of origin of a living creature or object.

Analysis of the text corpus from the social network Twitter

For analysis, a corpus of texts was selected, consisting of 134 publications on the twitter social network containing the Heimat token.

Based on the analysis of the lexical unit distribution, one can distinguish semantic dominants in the contexts of the Heimat token use, which can be combined into the following semantic groups:

1.

The conceptional aspect: a) location (country, city, place) (24): ..... und “Kindergeld” für die zahlreichen Kinder in der Heimat ??? (And what about the “child support” for numerous children in the homeland?), Dann kannst du dir ja meine heimat ansehen (Then you can look at my city). In this group, we included contexts that indicate a geographical location (city, country), but it cannot be unambiguously identified as where the communicant was born, where they came from.

b) place of origin of a living creature or object (20): Heimat von Schimanski, die größte Moschee Deutschlands, Loveparade Tragödie (The homeland of Shimansky, the largest mosque in Germany, the tragedy of Loveparade); Wären sie in ihrer Heimat geblieben, wäre das nicht passiert (If they had stayed at home, this would not have happened). Lexical markers were constructions

Heimat von / someone’s homeland , possessive pronouns, context as a whole (indicating return –“Also wenn ich mal wieder in der Heimat bin” (“So when I get home”)).

c) the construct of the road, the way home (23): Wollteste Dich selbst nach Hause fahren? Hab ich auch schon gemacht wennich S5 und Richtung Heimat Feierabend hatte (Did you want to take yourself home? I already did this when I was S5 and went home after work); Blumen für algernon von daniel keyes, mitgenommen weil ich nach der arbeit direkt in die heimat fahre (I took Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes with me because I’m going straight home after work).

The most frequent distribution: verbs of movement

(fahren / drive, kommen / arrive ), direction of movement or transport (Richtung / direction, S5 (highway),Zug / train, Bahn / railway ).

d) old / new homeland (12): Habe mit einem Kunden aus meiner EX Heimat telefoniert und habe angefangen in Dialekt zu antworten (I called the client from my former homeland and started answering the dialect); Zukünftige Heimat (ab morgen btw) (Future home (from tomorrow, by the way)). Lexical indicators

: EX / former, zukünftig / future, alt / old, neu / new, zweite / second.

e) the opposition of “there” and “here” (3): Im Ausland, in der Heimat (Abroad, at home); Er soll nur bitteschön in seiner Heimat trollen und nicht hier (He must troll only in his homeland, not here). Verbal markers were references to other countries

(Ausland / abroad; so viele Länder außerhalb der eigenen Heimat / so many countries besides [our] own homeland), the antithesis in seiner Heimat – hier / in their homeland – here.

2. The emotional aspect: a) affective-evaluative reactions (10): Denn die Menschen lieben Ihre Heimat (Because people love their homeland); Was macht eigentlich eure Heimat besonderst oder was verbindet ihr oder andere damit (What really makes your homeland most special or what you or others associate with it). Typical lexical surroundings were the verb of feelings lieben / love, the tokens Verbundenheit / connection, Geborgenheit / security, Verhältnis / attitude, the context.

b) connection with the past, memories (6): Wo wir waren war immer “zuhause”, die Heimat blieb der Ort der Kindheit (Where we were was always “at home”, the motherland remained a place of childhood); Zurück in der Heimat, zurück in Deutschland, zurück im Ruhrgebiet, zurück in der Straße in der ich lebte. Ich hatte hier die schlimmsten Jahre meines Lebens (Back in my homeland, in Germany, in the Ruhr region, on the street where I lived. I spent the worst years of my life here).

Lexical markers

: Kindheit / childhood, Geschichten / stories, Gedanke an / thought about, Schule / school, Ostern / Easter.

c) connection with ancestors, family (4): Die Familie ist die Heimat des Herzens (Family is the homeland of the heart); Ich darf nicht gleichberechtigt in meiner Heimat leben auf den Boden meiner Vorfahren (I am not allowed to live equally in my homeland, in the land of my ancestors). Lexical Markers:

Familie / Family, Vorfahren / Ancestors.

d) belonging, cultural affinity (3): Oder sich mit seiner heimat identifizieren und verwurzelt fühlen (Or to identify oneself with one's homeland and feel rooted); Wann ich an ming Heimat denk (dialect. When I think of my homeland). Lexical markers: Identität / identity, indentifizieren / identify, use of the dialect.

e) social affinity to the group (5): Und Heimat ist da, wo deine Freunde sind (And the homeland is where your friends are); Back to the roots, als Altnazis in der Partei eine Heimat fanden (Back to the roots when the old Nazis found their homeland in the party). Friends (

Freunde / friends ) and political organizations (CDU / CDU, Partei / party, AfD / AfD ) act as such groups.

e) loss (10): Dass man mit seiner Heimat mehr verliert als einen Fleck umgrenzter Erde (What you lose with your homeland is more than a limited piece of land); Aber das Auge wird hinter ihnen nach ihrer verlorenen Heimat suchen (But the look will hunt behind for the lost homeland). The concept of losing and gaining a homeland plays a significant role in communication. Language indicators are: verlieren / lose, vertreiben / expel, ban / ban, stehlen / steal, nehmen / withdraw.

g) homesickness (5): Jetzt zieht es Dich zurück in die Heimat (Now you feel drawn back to your homeland); Ich vermisse meine freunde und die heimat (I miss friends and homeland). Identified lexical environment:

Heimweh / homesickness, Sehnsucht / longing, vermissen / miss, erkranken / sicken, ziehen / draw.

3. Cultural and historical aspect: a) connection with ideology (5): Man muss kein #Nazi sein um seine #Heimat zu lieben (You don’t need to be a Nazi to love your homeland); Wer aber zu seiner deutschen Heimat steht ist dann was? Ein Nazi, Rassist oder sonstwas! (But whoever stands for his German homeland, who is he? A Nazi, a racist or the like!).

Typical is the use of indications of a political ideology, especially of the ultra-right or the ultra-left wings (Nazi / Nazi, Faschist / fascist, links und rechts / left and right).

b) patriotism (4): Ein Patriot ist daher auch nicht immer dort gebürtig, sondern einer der jenes Land als seine Heimat sieht (Patriot, therefore, is not always the one who is born here, but the one who considers this country to be his home); Allerdings wurde uns in der DDR zumindest die Liebe zur Heimat gelehrt (However, we were even taught in the GDR to love our motherland).

The indicators of this semantic group were the concepts of “patriot” and an indication of the upbringing of patriotism, as well as the need to protect the homeland.

Thus, the cognitive structure of the concept is as follows:

Outer periphery – 10.45% (opposition “there” and “here” (3); connection with ancestors, family (4); belonging, cultural affinity (3); patriotism (4)).

Analysis of the text corpus from the social network Twitter

The free associative experiment was conducted with German linguistic culture representatives in the cities of Fecht, Berlin, Potsdam, Freiburg, Baden-Baden. The age of respondents is 17–23 years. We chose this age of the respondents, because, following Karaulov (1981), we believe that the formation of a “linguistic personality” is completed by this period, and “the formed linguistic ability of the participant in the experiment is reflected in the associations” (p. 230).

200 reactions (single 38 reactions, failures 0, different answers 49) were received for the Heimat / homeland stimulus word. We distribute the reactions in accordance with the model of associative value by Pishchalnikova (2019) and highlight additional characteristics of the associates.

Since conceptional reactions usually correspond to the vocabulary meaning of the stimulus word, in the reactions one can distinguish indicators that will partially correspond to the cognitive characteristics of the Heimat / homeland lexeme that we have identified earlier. The same applies to representational reactions. In representational reactions that reflect the person’s emotional connection with the place, we see it appropriate to highlight additional indicators: homesickness, sense of security, family, sense of belonging, inner feelings, familiar surroundings.

-

1) a certain territory (country, city, place): Haus / house (15), Dorf / village (9), Land / country (9), Stadt / city (2) – total 35;

-

2) the emotional connection of a person with this place, the subjective feeling of "home": Zuhause / home (42) – total 42;

Sum total: 77

-

1) a specific territory (country, city, place): Deutschland / Germany (28), zu Hause / at home (15), Berlin / Berlin (9), Bad Bederkesa / Bad Bederkesa, Bad Zwischenahn / Bad Zwischenahn, Ausland / abroad, Bremen / Bremen, Bremervörde / Bremenförde, Goslar / Goslar, Kosovo / Kosovo, Vechta / Vechta, Weyhe / Weye (1) – total 61;

-

2) the emotional connection of a person with this place, the subjective feeling of "home" –total 55:

-

a sense of security: Geborgenheit / shelteredness, Schutz / protection, Sicherheit / security (1) –total 3;

-

homesickness: Heimweh / homesickness, Sehnsucht / longing (1) – total 2;

-

family: Familie / family (32), Freunde / friends, Mama / mother, meine Familie / my family, Mutter / mother (1) – total 37;

-

sense of belonging: Identität / identity (1) – total 1;

-

inner feelings: Liebe / love (2), mein Haus / my house (2), Harmonie / harmony, Heimatgefühl / sense of homeland, Kraft / strength, Wärme / warmth, wo der Liebste ist / where your loved one is, Wohlfühlen / feeling good (1) – total 10;

-

familiar environment: Himmel / sky, Kuh / cow, Menschen / people (1) – total 3;

-

Sum total: 116

First of all, we note that the distribution of reactions in accordance with the model of associative value is conditional. The greatest number of reactions are syncretic, that is, we can attribute them both to conceptions and to emotionally marked reactions or cultural reactions.

Conceptional reactions account for 38.5% of the reactions total number. As noted above, conceptional reactions correspond to the vocabulary meaning of a word. They indicate the territorial affiliation of the respondent and the place of his residence or birth. The concept of Zuhause / home is initially an emotional concept and is closely related in its emotional content to the concept under consideration. The reaction Zuhause / home is kernel and accounts for 21% of the total number of reactions. We can say that the very concept of Heimat / homeland has retained an explicit positive connotation in its psychologically relevant content. This statement is also confirmed by representational reaction.

The largest number of reactions are representational reactions (55.5% of the total number of reactions). It should be pointed out that this result is expected, since Heimat / homeland is one of the basic values of any society and should contain the personal attitude of the respondents.

As in the case of conceptional reactions, the largest number of reactions-representations (30.5%) are associated with a specific place of residence or place of birth for respondents. In 28 cases (14% of the total number of reactions), respondents called their motherland – Germany – homeland, which also indicates a sense of belonging to their culture.

27.5% of reactions reflect the person’s emotional connection with the place, the subjective feeling of “home”. A high percentage of the emotional component is also expected. We previously mentioned that basic values are, in fact, stereotypes, the formation of which is based on the emotional component (Khlopova, 2018a). For respondents, the homeland is a place that is primarily associated with family relationships, with friends and relatives. In this case, the token content is partially changed. It is the experiment that reveals the actual content of the lexeme, even if it is not noted in lexicographical sources, however, which is significant for respondents.

The respondents’ homeland is associated with positive internal feelings and evokes positive emotions: love, a sense of harmony and well-being. In addition, we especially emphasize the sense of shelteredness and safety that respondents associate with their homeland. The subjects call the items of their familiar environment as reactions, which also testifies to the sensation of a certain protection from external factors, since they have a protective function. In addition, respondents feel homesick, which indicates a deep attachment of respondents to their homeland.

To emotionally-evaluative reactions we assigned adjectives, which mainly give a positive assessment of the studied concept and partially reflect the previously identified additional characteristics: familiar surroundings (bekannt / familiar), inner feelings (fröhlich / joyful, schön / beautiful). The leer / empty response presents difficulties for the interpretation. It can indicate the absence of any feelings of the respondent, or it can only be a description of his native city, village, etc.

The cultural reaction Dialekt / dialect is associated with Germany. It is known that it is in Germany that there are a large number of dialects and regional variants, which is due primarily to historical prerequisites. The Flagge / flag reaction refers to the visualization of the German flag: gold, black red.

After analyzing the reactions, we model the associative field of the Heimat / homeland token. The core includes reactions with a coefficient of at least 5: Zuhause / home (42), Familie / family (32), Deutschland / Germany (28), Haus / house (15), zu Hause / at home (15), Berlin / Berlin (9), Dorf / village (9), Land / country (9).

Kernel reactions are mainly associated with the representation of the native home, place of residence or family. In addition, respondents identify themselves as members of German society, naming Germany as a kernel reaction. As a conclusion, we note that associative experiment notes the additional meaning of the Heimat / homeland token: a place that is associated with family relationships, with friends and relatives.

Conclusion

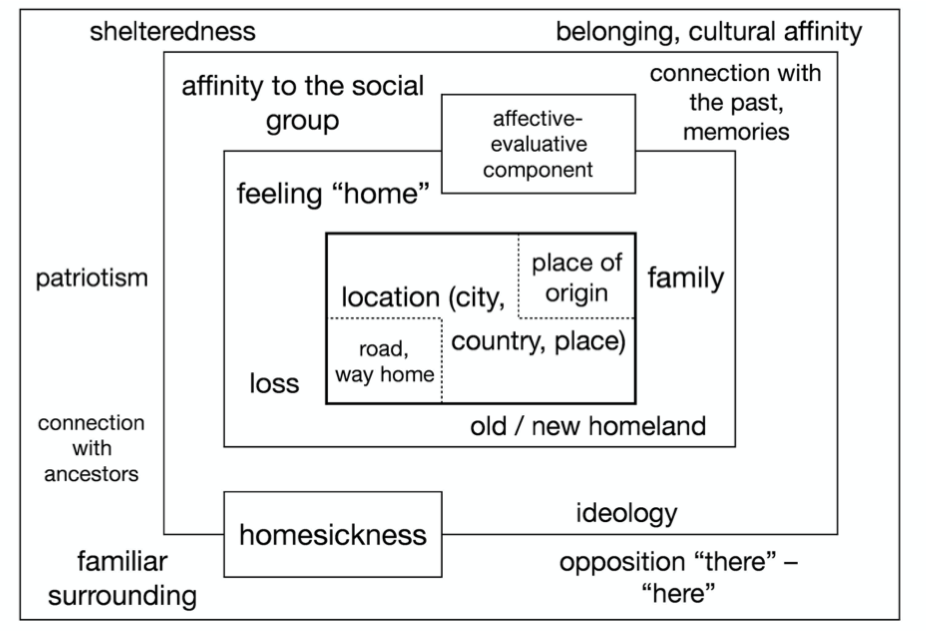

Based on the results, we can conclude about the semantic structure of the Heimat concept in German language culture (Figure

The core of the concept is the semantic attribute “territory (country, city, place)”, which also includes the image of the path / road home, as well as the meaning “place of origin of a living being or object”. These semantic features are also reflected in the vocabulary definition of the lexeme, which indicates their fundamental nature.

On the near periphery are the subjective feeling of “home”, the family, the concept of loss and gaining a homeland, as well as an idea of the old and a new homeland. These semantic features testify that the representatives of German language culture associate the idea of the homeland not only with the geographical location, but with subjective feelings of comfort, shelteredness, affinity to relatives. Since the homeland is no longer perceived as a specific land parcel, this logically implies the idea of the mobility of the homeland, the possibility of its change or loss.

According to the results of an associative experiment and cognitive analysis of the corpus of texts, the affective-evaluative component (which includes the emotional and evaluative components, in particular, the expression of a feeling of love for the motherland, its subjective assessment) is at the junction of the near and far periphery. It is noteworthy that, based on the results of the study, primarily markers of a positive assessment were identified, which indicates the axiological value of the concept for the language culture under consideration.

On the far periphery are affiliation with a social group (with the exception of family: in particular friends, colleagues, party members and other people), a connection with the past in the form of reminiscences, as well as a stable connection with a political ideology that uses the concept of homeland for propaganda purposes.

The outer periphery is made up of belonging to a cultural community, a sense of shelteredness, the opposition “there” – “here”, patriotism, a subjective feeling of safety, and also a connection with ancestors.

To conclude, we note that despite the different distribution of components within the semantic and associative fields, the components themselves coincide, which can verify the assumptions about the actual meaning of the Heimat / homeland concept. A cognitive analysis of the contexts with the lexeme and interpretation of the results obtained during the associative experiment were carried out independently of each other. The presence of correlation in the collected data indicates the reliability of the results.

Thus, we note that, despite the different distribution of components within the semantic and associative fields, the components themselves coincide, which can verify the assumptions about the actual value of the Heimat / homeland concept. However, a clear associative connection between the homeland and the family, marked as kernel in the associative field, appears in the semantic field only in the outer periphery. Internet communication proceeds in the conditions of unprepared, informal communication. Nevertheless, such communication takes place mainly between strangers. We assume that the family reaction among the respondents has a deeply personal meaning that may not appear in such communication. We believe that due to the fact that in a free associative experiment no restrictions are placed on the nature and number of reactions, this makes it possible to identify really functioning meanings that may not be actualized in other types of communication. Notwithstanding the foregoing, this hypothesis requires a more detailed consideration in future research.

References

- Ashkenazi, O. (2012). Homecoming as a national founding myth: Jewish identity and german landscapes in konrad wolf's i was nineteen. Religions, 3(1), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3010130

- Balandina, E., & Peredrienko, T. (2019). The model of psycholinguistic image analysis. XLinguae, 12(2), 3-16. https://doi.org/10.18355/XL.2019.12.02.01

- Bätzing, W. (1991). Kulturlandschaftswandel in der heutigen schweiz als verlust von heimat [Cultural landscape change in today's Switzerland as a loss of home]. Geographica Helvetica, 46(2), 86–88. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-46-86-1991

- Bubnova, I. A. (2019). Awards as Value Imperatives of a State and Society. Science Journal of Volgograd State University, 18(3), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.15688/jvolsu2.2019.3.7

- Daulet, F., Zeinolla, S., Omarova, M., Smagulova, K., Orazakynkyzy, F., & Anuar, S. (2019). Somatic cultural code and its role in the Chinese linguistic worldview (based on the concepts of “face” and “heart”). Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 7, 703–710. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2019.7490

- Gawda, B. (2019). The Structure of the Concepts Related to Love Spectrum: Emotional Verbal Fluency Technique Application, Initial Psychometrics, and Its Validation. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 48(6), 1339–1361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-019-09661-y

- Hornstein Tomić, C. (2011). The construction of identity and home(-lessness) in diaspora discourse. Drustvena Istrazivanja, 20(2), 415-433. https://doi.org/10.5559/di.20.2.07

- Jacobson, H. (2003). Home, Heimat, Haimish. Index on Censorship, 32(2), 27–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/03064220308537208

- Karaulov, J. N. (1981). Lingvisticheskoe konstruirovanie i tezaurus literaturnogo yazyka [Linguistic design and literary language thesaurus]. Moscow: Nauka.

- Khlopova, A. I. (2018a). Verbal'naya diagnostika dinamiki bazovyh cennostej [Verbal diagnosis of the basic values dynamics] (Doctoral dissertation). https://search.rsl.ru/ru/record/01009623686

- Khlopova, A. I. (2018b). Defying the Changes of Lexical Meaning in the Associative Experiment (on the Example of Lexeme ‘Delo’). Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya 2, Yazykoznanie [Sci-ence Journal of Volgograd State University. Linguistics], 17(2), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.15688/jvolsu2.2018.2.9

- Normurodova, N., & Sirojiddinov, S. (2019). Pragmatics and Cognition: Intention and Conceptualization in Discourse. International Journal of Advanced Computer Research, 9, 2888–2893. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijeat. A1177.109119

- Peterlini, H. K. (2010). “Heimat”-Homeland between life world and defence psychosis. Intercultural learning and unlearning in an ethnocentric culture: long-term study on the identity formation of junior “Schützen” (shooters). Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.051

- Pishchalnikova, V. A. (2019). Interpretation of Associative Data as a Methodogical Issue of Psycholinguistics. Russian Journal of Linguistics, 23(3), 749–761. https://doi.org/10.22363/2312-9182-2019-233-749-761

- Popova, Z. D., & Sternin, I. A. (2007). Semantiko-kognitivnyj analiz yazyka [Semantic-cognitive analysis of language]. Istoki.

- Schiller, M. (2018). Heino, rammstein and the double-ironic melancholia of germanness. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23, 261-280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549418810100

- Shaposhnikova, I. V. (2018). Psihoglossy, markiruyushchie civilizacionnuyu indentifikaciyu Rossijskih studentov (po materialam massovyh associativnyh eksperimentov) [Psychoglosses of the civilizational identity of russian students (based on large-scale associative experiments)]. Siberian Journal of Philology, 3, 255–273. https://doi.org/10.17223/18137083/64/23

- Sieberer, M., & Machleidt, W. (2015). Souls without a Home: The Situation of Asylum Seekers in Germany. Psychiatrische Praxis, 42, 175–177. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1387643

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

20 November 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-094-5

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

95

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1241

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, discourse analysis, bilingualism, multilingualism

Cite this article as:

Ladosha, O. M., & Khlopova, A. I. (2020). Cognitive-Semantic Analysis Of The Lexeme Heimat In Modern German Language. In Е. Tareva, & T. N. Bokova (Eds.), Dialogue of Cultures - Culture of Dialogue: from Conflicting to Understanding, vol 95. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 485-495). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.11.03.52