Abstract

The research aims to study the effectiveness of cross-border knowledge transfer from Japanese companies to their business affiliates in Northern Malaysia by looking into the knowledge context and the mediating effect of the business affiliates’ learning intent. Three aspects have been investigated under knowledge context, namely organizational culture, trust, and leadership. By focusing on the attributes identified in existing literature, it is believed that knowledge context would influence how effective cross-border knowledge transfer of Japanese business affiliates is in Malaysia. This relationship is also mediated by the Japanese business affiliates’ learning intent. By forming hypotheses based on existing literature, data was collected through survey questionnaires to test the significance of the proposed hypotheses. The results indicate that knowledge context such as organizational culture, trust, and leadership has significantly positive effects on the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysia, and that the business affiliates’ learning intent significantly mediates the relationship between knowledge context and the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer to Malaysia. The findings of this study could serve as a reference for business practitioners to improve knowledge transfer by fostering an organizational culture that encourages collective learning, establishing trust among employees to make information sharing more easily, as well as implementing effective leaderships that could guide employees to learn more proactively. All these would contribute to higher learning intent and thus result in more effective cross-border knowledge transfer.

Keywords: Cross-Border knowledge transferorganizational culturetrustleadershiplearning intentjapanese business affiliates

Introduction

Over the past few decades, famous multinational corporations such as Western Digital have left Malaysia for various reasons related to the economic conditions of the local market, whereas other corporations have left to seek a more conducive business environment in consideration of lower operation costs. It has been observed that most of the multinational corporations that cease operation in Malaysia are from western countries while many of those that remain operating in Malaysia till this day are multinational corporations affiliated with Japanese companies. As such, what is the reason behind the long-term sustainability of these Japanese affiliated companies in Malaysia?

Long before the industrialization of the Malaysian economy, the main contributors to the economy were agriculture and mining, with agriculture contributing to employment rate of 37% and Gross Domestic Product’s rate of 28% in the mid-1970s (Yahya, 2000). Although Malaysia was actively exporting rubber and tin, and eventually became one of the top exporters of such products, the overall economy in Malaysia was still not up to par. Majority of the families were not earning enough and were still struggling to get out of poverty, especially households in the Peninsular. In order to reform the economy, the New Economic Policy was introduced. Development aid was given to the primary sectors such as agriculture, with the priority to encourage the growth of export-oriented industrialization (Drabble, 2000).

This was followed by the establishment of the Free Trade Zone in Penang in 1972 whereby firms located there enjoyed several benefits such as the imports of capital goods and raw materials that are duty-free, and complete or partial exemptions from taxes for foreign investors who came to Malaysia for the relatively low wages, comprehensive infrastructure, high number of knowledge workers, and docile trade unions. The last phase of establishing the Free Trade Zone was completed in the 1990s. As such, industries such as chemicals, telecommunications equipment, electrical and electronic machinery and appliances, car assembly and other heavy industries grew substantially. Under the New Economic Policy, Malaysia transited to become a nation with manufacturing and services industries emerged as the leading growth sectors.

Following the substantial economic growth in Malaysia, many multinational corporations and foreign firms were attracted to the viability of the Malaysian market. Therefore, the inflows of Foreign Direct Investment also increased as more firms entered Malaysia to look for a better prospective business environment. One of the pioneer batches of multinational companies that started investing heavily in Malaysia were Japanese firms. For instance, the business partnership between Malaysia’s national car brand Proton and Japanese firm Mitsubishi set up plants to assemble cars in the country had brought much success to the country’s automobile industry. Electronic giant Panasonic had also set foot in Malaysia since 1976 to expand its international presence in South East Asia. Other than the attractive policies by the Malaysian government that drew in large influx of foreign investors, one possible reason that motivated the Japanese firms to actively expand their business overseas could have be their country’s stagnant economy, as shown by the plunge in Japan’s Gross Domestic Product between 1960 and 1980. The economy suffered further and slowed down from 1981 to 2009 (Drabble, 2000; The World Bank Group, 2017). In order to sustain their businesses, Japanese firms had to go cross border in search of a more conducive business environment.

From the year 2008 to 2014, Japan remained one of the biggest sources of Foreign Direct Investment for Malaysia (Bank Negara Malaysia & Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia, 2019). In terms of sectors, most of Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment was poured into the manufacturing sector in the 1990s (Urata, 2002). Nevertheless, this trend changed post 2000 as Japan’s focus shifted to the non-manufacturing sector such as services and finance, and insurance (Ministry of Finance Japan, 2018). This could indicate that the Malaysian manufacturing sector was losing its attractiveness, thus causing the Japanese to inject their Foreign Direct Investment to other countries with lower manufacturing costs. However, it is also possible that the Malaysian service sector had become more competitive in terms of knowledge as the main resource. Either way, the substantial changes in the sectoral composition from 1990s to post 2010 show that there is no guarantee for constant increase in any specific sector; Japan could divert their Foreign Direct Investment to other countries should Malaysia lose its business competitiveness and attractiveness. It is important to look into ways to improve knowledge acquisition and investigate the factors that contribute to a more effective cross-border knowledge transfer. By doing so, businesses in Malaysia could become more competitive and make the operations more sustainable in the long term.

Several factors that facilitate knowledge transfer such as the value of knowledge stock, channels to transfer knowledge, motivation and ability to transfer knowledge, and absorptive capacity (Brookes & Altinay, 2017; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000; Khamseh & Jolly, 2008; Welch, 2015) have been identified in existing literature. These studies have provided a concrete and strong base for further research in the field of knowledge transfer. In this study, knowledge context has been studied and investigated for its influence on the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Northern Malaysia, with the mediating effect of organisation’s learning intent. Based on the existing literature, knowledge context in this study focuses on 3 aspects, namely organisational culture, trust, and leadership.

Knowledge Context

Knowledge context is the unique condition that people can communicate with each other and apply their know-how in decision making. It is the condition in which knowledge is constructed, exchanged, and utilized. Knowledge can move in different conditions such as by forming networks among business partners and firms, considering the effects of cultural differences has on the organizational cultures, building trust, and also choosing relevant leadership styles to facilitate knowledge flow (Loebbecke et al., 2016). Wei and Miraglia (2017) found that in knowledge transfer, organisational culture has its important role because it is a type of context that affects how business partners and employees form interpersonal relationships that foster trust, and how the managers lead so that they could encourage knowledge sharing and knowledge acquisition. However, there have been inconsistent findings about the effects of knowledge context on knowledge transfer (Sergeeva & Andreeva, 2016). Therefore, the three aspects that contribute to knowledge context in effective knowledge transfer, namely organizational culture, trust, and leadership, are studied in this research. In this way, the study aims to find out if they are positively significant to the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysia.

Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is defined as the values that contribute to the unique interactions and communication between different people in an organization, the shared underlying beliefs, and assumptions. In the corporate world, businesses may expand their presence internationally for various reasons including availability for more resources, penetrating untapped markets, searching for more business-conducive environments and so on. But as they expand, they bring along their organizational culture to the host country. Communication across different levels and hierarchies intra- and inter-organization is very much affected by the organizational culture (Wei & Miraglia, 2017). Organizational culture plays a big role on whether or not information and knowledge can be transferred effectively because it affects the way people act and interact in an organization. Many multinational corporations manage to perform well even though they have employees of different nationalities, and cultural differences no longer seem to be a major obstacle in the workplace. This is because common shared organizational work practices can actually override the influence of national culture (Bititci et al., 2006; Marshall et al., 2016). This puts managers and employees (some of whom are expatriates) in the spotlight because they are the facilitators of information (Reiche et al., 2017) and their organizational practices contribute to a unique organizational culture that could affect the effectiveness of knowledge transfer. Managers also act as a bridge between employees because if they lead their subordinates well, trust will be established and the involved parties are more likely to share and/or acquire information and knowledge (Higuchi & Yamanaka, 2017; Koohang et al., 2017). As Japanese organizational culture is shaped by the very strong rituals present in Japanese management styles (Elvin & Johansson, 2017; Jakonis, 2009; Yusof & Othman, 2016), they do not really fit into any of the existing types of organizational cultures. Hence, in this study, the Japanese organizational culture has been investigated to determine its influence on the effectiveness of cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysia.

Trust

Trust has been shown to build collaboration and improve adaptability, lower expenses of collaborating and organising activities as well as enhance the transfer of knowledge and potential for learning (Higuchi & Yamanaka, 2017). There are many ways to build trust, including grapevine communication. In the business context, grapevine communication is known as the corporate socialization mechanism (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000; Treem et al., 2018) in which organizational mechanisms that are built on familiarity and personal affinity. As the relation recognition and affinity among co-workers and superiors grow greater, the openness of communication among interacting parties also increase. According to the study done by Higuchi and Yamanaka (2017), a good relationship between business partners can increase the knowledge recipients’ trust on the supply side’s ability and good-faith. This will lead to higher learning intents. A study by Ouakouak and Ouedraogo (2019) found similar results. Japanese firms are known to adopt more intensive use of mechanisms. For example, the mechanisms include formal gatherings, workshops, move of employees to specialty units and rotation of jobs to create a cross-organization culture with trust. To form deeper trusting relationships, the Japanese are also said to have a preference for having socialization outside the work setting (Elvin & Johansson, 2017; Higuchi & Yamanaka, 2017; Merchant, 2018). The level of trust as well as the scope and scale of shared organizational resources is said to be able to facilitate the willingness to acquire knowledge from the parent company (Sasaki et al. , 2016). Hence, this can lead to higher learning intentions from the Malaysian business partners and subsequently make knowledge transfer more effective.

Leadership

Leadership style is another aspect of knowledge context about a leader’s method of giving guidance, actualizing plans, and giving people a lot of motivation to work toward something. Various types of leadership styles would affect the process of knowledge transfer differently. There are many types of leadership styles such as the Laissez-Faire leadership, the autocratic leadership, the participative leadership, the transactional leadership, transformational leadership, and the coaching leadership (Johnson, 2018). One of the most suitable and effective leadership styles is transformational leadership (Yusof & Othman, 2016). Transformational leaders tend to have very good ability to identify and handle one’s emotions. They also encourage and motivate others with a common and mutual vision of future. These leaders are usually very skilled in communication and thus, are capable of effectively motivating team members who strive hard to acquire knowledge for personal development and workplace achievement (Para-González et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). When this happens, the learning intent will increase greatly and employees will be bound to connect more effectively in the process of knowledge transfer. According to Taka and Foglia (1994), Japanese business affiliates’ management leadership style such as self-realization, appreciation of diverse abilities and trust in others play crucial role in fostering strong learning intention. Likewise, Koohang et al. (2017) study found that effective leadership styles can bring out the engagement and enthusiasm in employees to learn. Therefore, leadership style has been studied as another aspect of knowledge context to determine if it positively affects the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysia.

Learning Intent

Learning intent is the Japanese business affiliates’ intention to acquire new knowledge and the level of effort they devote towards solving problems. One of the pioneering scholars who came up with the topic of learning intent is Hamel (1991) who defined learning intent as the propensity of a firm to see joint effort as a chance to learn. Problem-solving is said to be one of the characteristics of Japanese management; many Japanese firms are known to actively encourage their employees to constantly look for problems and issues as these are viewed as a good chance to learn and improve. The process of the transfer of knowledge will speed up when the learning intent is strong (Pérez-Nordtvedt et al., 2008). If an organization is very motivated to learn new knowledge, its openness and receptiveness to new knowledge will ease the transfer of knowledge as well as allow for a quicker and more effective transfer.

Problem Statement

Even though Foreign Direct Investment from Japan has been quite consistent over the years, it is important to avoiding becoming complacent about this. After all, the global business environment is becoming very competitive as companies from all over the world strive to lower down operation costs while trying to remain innovative. As such, overall product life cycle is cut short and many businesses struggle to survive when faced with intense price wars that render traditional competitive advantages obsolete. It is possible that Japanese companies may shift their operations to other countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia to cut costs when they find Malaysia to be no longer an attractive business partner.

Meanwhile, Japanese Foreign Direct Investment to the country as well as the Research and Development funds pumped in by the Malaysian government has been gradually increasing over the years (The Global Economy, n.d.). Recent news have also reported that more Japanese companies are looking forward to setting up business operations in Malaysia (Foon, 2017). At the same time, some local firms in Malaysia are still struggling to cope with the fast-changing technology. On the other hand, those that work closely with their Japanese business partners have not really made any big leaps in technology advancement but remain as followers in the industry. The lack of innovativeness is reflected in the global innovative ranking. It shows that Malaysia’s position has not made any big improvement in recent years; it went from 35th in 2016 to 37th in 2017 before climbing up to 35th again (Cornell University, INSEAD, & World Intellectual Property Organization, 2018).

Many Malaysian companies have been working with their Japanese business partners for decades. In these cases, they should have acquired substantial new knowledge after years of cooperation and could assimilate this knowledge to create new independent knowledge. However, the firms’ struggle to catch up with the rapid change in technology and the decreasing position in global innovative ranking, thus leading to the question of the effectiveness of cross-border knowledge transfer between Japan and Malaysia.

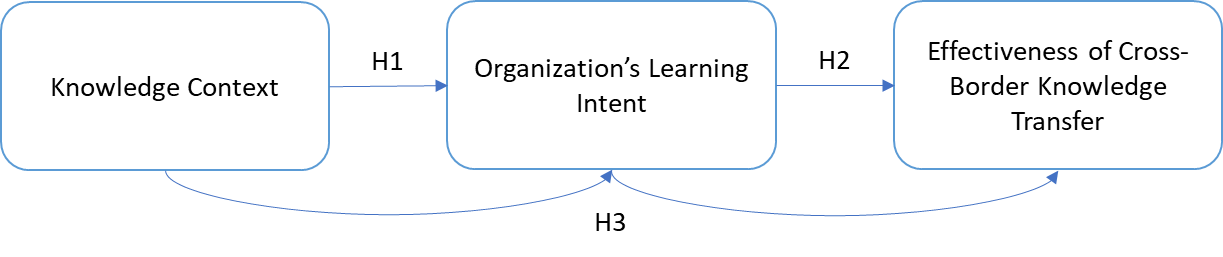

By adopting and referencing the frameworks from Pook et al. (2017) and Pérez-Nordtvedt et al. (2008), knowledge context was adopted as the independent variable, cross-border knowledge transfer’s effectiveness was adopted as the dependent variable, and the Japanese business affiliates’ learning intent was introduced as the mediating variable as shown in Figure

Based on the proposed conceptual framework, three hypotheses were formed.

H1: Knowledge context (organisational culture, trust, and leadership) is positively related to the organisation’s learning intent.

H2: Organisation’s learning intent is positively related to the effectiveness of cross-border knowledge transfer.

H3: Organisation’s learning intent significantly mediates the relationship between knowledge context and the effectiveness of cross-border knowledge transfer.

Research Questions

Based on the fundamental ideas behind this study, the background of study and the problem statement, three research questions have been identified:

Is knowledge context (organisational culture, trust, and leadership) positively related to the organisation’s learning intent?

Is the organisation’s learning intent positively related to the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysia?

Does the organisation’s learning intent mediate the relationship between knowledge context and the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysia?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of knowledge context on the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysia. By reviewing and referencing existing writing in the field of knowledge transfer, several facilitating factors that contribute to knowledge transfer have been identified by scholars. However, many of the existing researches were done in advanced countries such as the United States, China, and other European countries (Chen et al., 2010; Millar et al., 2017; Ouakouak & Ouedraogo, 2019; Para-González et al., 2018; Treem et al., 2018). Studies done in developing countries are limited. The results could be different if sufficient research has been conducted in developing countries; there are key differences in advancement in technology, political and legal systems, economic situation such as existing trade links and infrastructure in developing countries. Therefore, by doing this research study, it is also hoped that the results would contribute to the existing literature on knowledge transfer to developing countries such as Malaysia. The results of this study could serve as a reference for business practitioners to improve knowledge transfer by fostering an organizational culture that encourages collective learning, establishing trust among employees to make information sharing more easily as well as to lead with effective leaderships that could guide employees to learn more proactively.

Research Methods

As this study adopts part of the frameworks used by Pook et al. (2017) and Pérez-Nordtvedt et al. (2008), the methodology used in this study is the same as the authors. The study utilizes quantitative approach by distributing a questionnaire survey. By using G*power, the sample size was determined to be 77. In order to obtain 77 sets of response, a total of 154 sets of questionnaires were mailed out by post. A subset of manufacturing companies and services companies operating in Malaysia that have parent companies, joint venture partners and alliance affiliates in Japan were chosen as the sample population for this study. These targeted companies were identified from the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM) directory of Malaysian Industries 2017 (48th Edition). The target respondents were the key employees of Japanese business affiliates such as directors, managing directors, chief executives, and operation managers, as long as they were the most senior executive listed in the directories that were being referenced in this study. This group of target respondents were selected as they would have deep and comprehensive knowledge about the daily business operation. The unit of analysis was the organisation.

This study measured all dependent and independent variables with the defined dimensions. Likert type scales of 1 to 5 were used to measure all constructs. All questions were closed ended in order to avoid misinterpretation and eliciting irrelevant or confusing answers as well as obtain responses that are easier to analyse. The measurement model is a validity test to make sure the instrument is relevant to the study. The goodness of data in this study was assured by using validity tests as well as reliability analysis. Both validity and reliability analyses were utilized to ensure the instruments created estimate more precisely and consistently the concepts of this study. For validity testing, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity as well as discriminant validity tests were conducted. The data obtained from this study were analysed using Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis using the Smart PLS software which is commonly used in Structural Equation Model (SEM). A pre-test of the questionnaire was done even though the survey is adopted from an existing study (Pook et al., 2017) which had tested it. This ensured that the questions are understood by respondents and reduced ambiguity in the questions. Last but not least, the control variable in this study is the type of business structure, which in this case comprises of wholly-owned subsidiaries and joint-ventures.

Findings

For this research study, quantitative method was deployed by distributing survey questionnaires. There were a total of 44 questions that were categorized into four sections. The overall response rate is satisfactory with 52.6% or 81 sets returned answered questionnaires. A one-time follow-up reminder was sent to the same target respondents have further supported existing research that it does improve the overall response rate.

To test measurement models, convergent validity tests, internal consistency reliability test as well as discriminant validity tests were conducted. The results are shown in Table

Next, bootstrapping was carried out to determine the path coefficient. The results are shown in Table

As this research study has a mediator, mediating analysis was carried out to test the significance of the relationship. The results are shown in Table

Conclusion

The 3 aspects discussed under knowledge context are organisational culture, trust, and leadership. The first aspect that affects an organisation’s learning intent would be the organisational culture. Although Japanese culture and Malaysian culture share some similarities due to geographic proximity, the Japanese management style that was discussed in earlier sections is a prominent management style that shapes a distinct organisational culture that is different compared to other types. One of the prominent characteristics of the Japanese management style is the intensive and extensive job-training that Japanese companies give to their employees (Imaoka, 1985; Mawdsley & Somaya, 2016; Nakano, 1985). The exchange of personnel such as sending employees from Japan headquarters to be based in the Malaysian branch to oversee the business and sending Malaysian employees to the headquarters for skills training shows that the Japanese put a lot of emphasis on learning (Pucik, 1988). This has shaped an organisational culture that encourages learning among employees, be it in the organisation itself or cross-border learning from overseas partners. Some feedbacks given by the respondents also show that giving new ideas for new business opportunities are highly supported and encouraged. Across the organization, the general willingness to work together is present. Therefore, they are very motivated to learn new things because of this organisational culture. Japanese companies are willing to guide and teach the business affiliates especially wholly-owned subsidiaries by the Japanese corporations because by promoting growth, they can increase business efficiency and productivity of the business affiliates as well as help them to sustain businesses overseas.

Another well-known characteristic of the Japanese management style is the emphasis on employee involvement and human relations. This is because the Japanese see it as an important way to form interpersonal relationships and foster trust among co-workers. For instance, a few research found that co-workers are expected to join after-work socializing events such as having dinner and drinks together (Elvin & Johansson, 2017; Higuchi & Yamanaka, 2017; Merchant, 2018). The emphasis on in-group relationships is famous in Japanese organisations because it is a way of sharing more confidential information including tacit knowledge and thus, making the exchange of information among in-group members more easy and effective. The Japanese emphasis on employee involvement and human relations to establish trust and close acquaintanceship has enabled the involved parties to feel a sense of belonging. Thus, it eases the process of information exchange; this encourages Japanese business affiliates’ learning intent because of the in-group openness of communication. The trusting relationship between Japanese companies and their overseas business affiliates also results in the affiliates having higher motivation to learn novel things from their Japanese business partners because they trust their credibility and willingness to share knowledge. Because of this, tacit knowledge transfer becomes highly effective (Zerbino et al., 2018). The research results show that the trusting relationship between Japanese companies and their Malaysian business affiliates does encourage the latter to acquire new knowledge. Other studies have found that trust could foster knowledge creation (Sankowska, 2016; Sasaki et al., 2016).

Besides that, the management leadership style of Japanese business affiliates such as self-realization, appreciation of diverse abilities and trust in others (Taka & Foglia, 1994) also play a crucial role in fostering a strong learning intention (Islam et al., 2015). From the research results, the respondents concurred that the managers encourage employees to ask questions when they have things that they do not understand, articulate information and data across the organization, and express enthralling and captivating vision, and strategies so that employees take part in cross-border knowledge transfer. When managers and leaders are very encouraging to their subordinates in terms of exchanging information, it reduces the psychological barriers that prevent them from approaching their Japanese counterpart (Koohang et al., 2017). This allows a working environment that is open and flexible where people can teach and learn freely.

In addition to that, the analysis results also show that knowledge context has an indirect effect on the effectiveness of cross-border knowledge transfer. This means the business affiliates’ learning intent mediates the relationship between knowledge context and the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysia. In an organisational culture that encourages learning and emphasizes on employee relations, employees will find opportunities in this good ecosystem to explore different things and learn new knowledge. This is also supported by a recent research done by Chou and Ramser (2018). Working under a good leadership style that encourage employees to see problems from different angles and encourage them to share their opinion throughout the company will also make them feel as though they can trust their subordinates. All these provide the Japanese business affiliates in Malaysia a good environment to learn and hence, it contributes to a more effective cross-border knowledge transfer to the Malaysian counterparts.

This study contributes to the existing body of research by providing a framework for studying the influence of knowledge context on the effectiveness of Japanese business affiliates’ cross-border knowledge transfer in Northern Malaysia. By looking into different aspects of knowledge context such as organisational culture, trust, and leadership, both researchers and business practitioners could refer to the findings in order to gain better insight into improving the effectiveness of cross-border knowledge transfer. The tests on the mediating effect of organisation’s learning intent also provides new insight and confirms that in facilitating the transfer of knowledge, learning intent plays a significant role, especially its less explored mediating effect in the literature of knowledge transfer. To address the problem statement of this study, Malaysian business affiliates should try to shape an organisational culture that gives appreciation to workforce that is of diverse abilities, puts emphasis in self-realization, and trust in others. This will help to increase the organisation’s learning intent and lead to more effective cross-border knowledge transfer. Hopefully, by focusing on these aspects, the Japanese business affiliates in Malaysia could absorb new knowledge more effectively and grow to become more innovative, competitive and capable business partners to foreign companies.

References

- Bank Negara Malaysia & Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia. (2019). Monthly Highlights and Statistics in Mar 2019.http://www.bnm.gov.my/index.php?ch=en_publication_catalogue&pg=en_msb&ac=268&lang=bm

- Becker, J.-M. (2015). Composite relaibility. http://forum.smartpls.com/viewtopic.php?f=5&t=3805

- Bititci, U. S., Mendibil, K., Nudurupati, S., Garengo, P., & Turner, T. (2006). Dynamics of performance measurement and organisational culture. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 26(12), 1325–1350.

- Brookes, M., & Altinay, L. (2017). Knowledge transfer and isomorphism in franchise networks. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 62, 33–42. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.11.012

- Chen, J., Sun, P. Y. T., & McQueen, R. J. (2010). The impact of national cultures on structured knowledge transfer. Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(2), 228–242.

- Chou, S. Y., & Ramser, C. (2018). A multilevel model of organizational learning. The Learning Organization, 26(2), 132–145.

- Cornell University, INSEAD, & World Intellectual Property Organization. (2018). The Global Innovation Index 2018: Energizing the World with Innovation.

- Drabble, J. H. (2000). An Economic History of Malaysia, c.1800-1990: The Transition to Modern Economic Growth. Springer.

- Elvin, G., & Johansson, E. (2017). The impact of organizational culture on information security during development and management of IT systems : A comparative study between Japanese and Swedish banking industry (Dissertation). Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-324923

- Foon, H. W. (2017). Japanese investments are looking up. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/05/28/japanese-investments-are-looking-up-as-japanese-business-sentiment-begins-recovering-amid-optimism-o/

- Franke, G., & Sarstedt, M. (2019). Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: a comparison of four procedures. Internet Research, 29(3), 430-447. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-12-2017-0515

- Gupta, A., & Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge Flows within Multinational Corporations [Electronic version]. Strategic Management Journal, 21(4), 473–496.

- Hamel G. (1991). Competition for competence and inter-partner learning within international strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12(1991), 83–103.

- Higuchi, Y., & Yamanaka, Y. (2017). Knowledge sharing between academic researchers and tourism practitioners: a Japanese study of the practical value of embeddedness, trust and co-creation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(10), 1456–1473. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1288733

- Imaoka, H. (1985). Japanese Management in Malaysia. Japanese Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 22(4), 339–356. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/tak/22/4/22_KJ00000131185/_article/-char/ja/

- Islam, M. Z., Jasimuddin, S. M., & Hasan, I. (2015). Organizational culture, structure, technology infrastructure and knowledge sharing: Empirical evidence from MNCs based in Malaysia. Vine, 45(1), 67–88.

- Jakonis, A. (2009). Culture of Japanese organization and basic determinants of institutional economy. Journal of Intercultural Management, 1(2), 90–104.

- Johnson, R. (2018). 5 Different Types of Leadership Styles. http://smallbusiness.chron.com/5-different-types-leadership-styles-17584.html

- Khamseh, H. M., & Jolly, D. R. (2008). Knowledge transfer in alliances: Determinant factors. Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(1), 37–50.

- Koohang, A., Paliszkiewicz, J., & Goluchowski, J. (2017). The impact of leadership on trust, knowledge management, and organizational performance: A research model. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 521–537.

- Loebbecke, C., van Fenema, P. C., & Powell, P. (2016). Managing inter-organizational knowledge sharing. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 25(1), 4–14. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2015.12.002

- Marshall, D., Metters, R., & Pagell, M. (2016). Changing a Leopard’s Spots: A New Research Direction for Organizational Culture in the Operations Management Field. Production and Operations Management, 25(9), 1506–1512.

- Mawdsley, J. K., & Somaya, D. (2016). Employee Mobility and Organizational Outcomes: An Integrative Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. Journal of Management, 42(1), 85–113.

- Merchant, Y. S. (2018). 5 major differences between Japanese and American workplaces. https://www.businessinsider.com/differences-between-japanese-and-american-work-culture-2018-3/?IR=T/#japanese-workplaces-are-more-formal-1

- Millar, C. C. J. M., Chen, S., & Waller, L. (2017). Leadership, knowledge and people in knowledge-intensive organisations: implications for HRM theory and practice. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(2), 261–275. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1244919

- Ministry of Finance Japan (2018). Japan Direct Investment Flows 2018C.Y. https://www.mof.go.jp/english/international_policy/reference/balance_of_payments/ebpfdii.htm

- Nakano, H. (1985). A Commentary on Hideki Imaoka’s “Japanese Management in Malaysia.” Japanese Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 23(1), 109–115. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/tak/23/1/23_KJ00000131208/_article/-char/ja/

- Ouakouak, M. L., & Ouedraogo, N. (2019). Fostering knowledge sharing and knowledge utilization. Business Process Management Journal, 25(4), 757–779.

- Para-González, L., Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Martínez-Lorente, A. R. (2018). Exploring the mediating effects between transformational leadership and organizational performance. Employee Relations, 40(2), 412–432.

- Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., Kedia, B. L., Datta, D. K., & Rasheed, A. A. (2008). Effectiveness and efficiency of cross-border knowledge transfer: An empirical examination. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 714–744.

- Pook, A. S. Y., Chong, C. W., & Yuen, Y. Y. (2017). Effectiveness of cross-border knowledge transfer in Malaysian MSC status corporations. Knowledge Management and E-Learning, 9(1), 90–110.

- Pucik, V. (1988). Strategic Alliances, Organizational Learning, and Competitive Advantage. The HRM Agenda, 27(1), 77–93.

- Reiche, B. S., Harzing, A.-W., & Pudelko, M. (2017). Why and How Does Shared Language Affect Subsidiary Knowledge Inflows? A Social Identity Perspective. Language in International Business, 209–253.

- Sankowska, A. (2016). Trust, knowledge creation and mediating effects of knowledge transfer processes. Journal of Economics and Management, 23(1), 33–44.

- Sasaki, M., Washida, Y., Uehara, W., Fukutomi, G., & Fukuchi, H. (2016). Managing Foreign Subsidiaries in Emerging Countries: Are They Different from Western Subsidiaries? In Marketing Challenges in a Turbulent Business Environment. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19428-8_80%0A

- Sergeeva, A., & Andreeva, T. (2016). Knowledge Sharing Research: Bringing Context Back In. Journal of Management Inquiry, 25(3), 240–261.

- Taka, I., & Foglia, W. D. (1994). Ethical Aspects of ’ Japanese Leadership Style ". Journal of Business Ethics, 13(2), 135–148.

- The Global Economy (n.d.). Malaysia: Research and development expenditure. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Malaysia/Research_and_development/

- The World Bank Group. (2017). GDP growth (annual %) - Japan. The World Bank Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2017&locations=JP&start=2010&view=chart

- Treem, J. W., Kuhn, T., & Barley, W. C. (2018). Valuing multiple trajectories of knowledge: A critical review and agenda for knowledge management research. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 278–317.

- Urata, S. (2002). Japanese Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia with Particular Focus on ASEAN4. In Conference on Foreign Direct Investment: Opportunities and Challenges for Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Waseda University.

- Wang, G., Van Iddekinge, C. H., Zhang, L., & Bishoff, J. (2019). Meta-analytic and primary investigations of the role of followers in ratings of leadership behavior in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(1), 70–106.

- Wei, Y., & Miraglia, S. (2017). Organizational culture and knowledge transfer in project-based organizations: Theoretical insights from a Chinese construction firm. International Journal of Project Management, 35(4), 571–585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.02.010

- Welch, L. S. (2015). The emergence of a knowledge-based theory of internationalisation. Prometheus (United Kingdom), 33(4), 361–374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08109028.2016.1207874

- Yahya, T. M. B. T. (2000). Crop Diversification in Malaysia. In Crop Diversification in the Asia-Pacific Region. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Yusof, S. M., & Othman, R. (2016). Leadership for Creativity and Innovation: Is Japan Unique? Journal of Advanced Management Science, 4(2), 176–180.

- Zerbino, P., Aloini, D., Dulmin, R., & Mininno, V. (2018). Knowledge Management in PCS-enabled ports: an assessment of the barriers. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 16(4), 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2018.1473830

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-087-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

88

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1099

Subjects

Finance, business, innovation, entrepreneurship, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Foong, W. M., & Chelliah, S. (2020). Investigating Japanese Business Affiliates’ Cross-Border Knowledge Transfer In Northern Malaysia. In Z. Ahmad (Ed.), Progressing Beyond and Better: Leading Businesses for a Sustainable Future, vol 88. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 816-828). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.74