Abstract

The association between merchants and customers is much more complex nowadays as a result of high customers' expectations. Hence, more companies are focusing on establishing consumer dialog and participation as a powerful means of establishing firm performance. To address the issue, this research aims to develop and test a version to scrutinize the effect of customer involvement on brand equity among SMEs. This study employed the theory by Thibaut & Kelley on social exchange to explain the interactions between customer-service providers in terms of value co-creation. Based on a sample of 548 customers from SMEs, results reveal that formation seeking, responsible behavior, and personal interaction have a statistically significant influence on brand equity. The results of this study make a significant input to the present literature on customer involvement in SMEs. However, the location of this study was conducted in Kuala Lumpur which marks the limitation and should be addressed by the next researchers.

Keywords: Brand equitycustomer participation behaviorSMEs

Introduction

The rapid growth in ICT (information and communication technologies) has encouraged more small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to engage in service industries. Services industries have become the backbone of most countries and have a significant contribution to a nation’s economy ( Oláh et al., 2018). SMEs play an important role particularly in providing employment opportunities, generating income for many households and producing an inclusive and balanced growth in Malaysia ( SME Corporation Malaysia, 2012). As a result, various programs have been implemented to assist SME retailers to have better opportunities to grow. In 2014, a total of 133 programs are being implemented by the Government to develop SMEs with a financial commitment of almost RM7 billion which benefits to 484,000 SMEs ( SME Corporation Malaysia, 2014). In a contrary perspective, SME enterprises especially owned by Bumiputera are facing many challenges to compete with the Large Format Growth stores such as Giant and Tesco ( Ahmad et al., 2010).

Literature review and hypotheses development

Customer participation behavior and brand equity

This study interprets co-creation value interest as a wide customer involvement in the co-creation and revamping of product or service ( Kristensson et al., 2008). Fuat Firat et al. ( 1995) introduced the value co-creation concept as an extension of the concept of ‘customization’. The purpose of this concept is to increase business growth through business performance and client engagement by focusing on the buyer-centric approach in a mass-customization process. Bendapudi and Leone ( 2003) provide empirical evidence that the presupposition of bigger flexibility beneath co-production can only appear if the consumer gets the know-how to co-create a service that is important to their attention. In this regard, this research is focusing on basic service retails by SMEs which are highly related to customers’ liking. Moreover, such positions can build a partnership between consumers and retailers in many ways, such as improving feedback from customers ( Kelley et al., 1990), enhancing perceived client satisfaction ( Bitner et al., 1997; Dabholkar, 1990) and innovative service and developing new products ( Matthing et al., 2004).

Previous research such as Yi et al. ( 2011) has identified two categories of value co-creation behavior namely, customer participation and customer citizenship behavior. Customer participation behavior is important for value co-creation practice since it's considered an in-role behavior of the consumer without which co-creation practices are not possible ( Shamim et al., 2015). As further mentioned by Yi and Gong ( 2013), customer participation behavior is personal interaction, information seeking, responsible behavior, and information sharing behavior. Meanwhile, customer citizenship behavior contains of tolerance, advocacy, feedback, and help is considered as extra-role behavior where customer acts beyond loyalty during the co-creation with the firm ( Yi & Gong, 2013). It will be an added advantage for other customers and the firm to have further value co-creation if it is implemented ( Shamim et al., 2015). Thus, the customer value co-creation behaviour (CVCB) is conceptualized as voluntary behavior that gives the firms and consumers’ extraordinary value ( Yi et al., 2011; Yi & Gong, 2008).

Researchers suggested that this approach is important for service retail studies as it emphasizes the awareness of the interrelated network of individuals together with organizations ( Lusch et al., 2007). Under co-creation and value-creating processes, customer participation and involvement as a co-creator of value will contribute to distinct customer experience ( Payne et al., 2008). The purpose of co-creation is to enhance a business culture that concentrates on curiosity, cooperation, and communication; consequently, it contributes to the creation of new products and services ( Lafley & Charan, 2008; Shaw et al., 2011). Similarly, Pine, and Gilmore ( 1999) offered for the experience of economic dimensions or traits, that is service experience must be tangible and could define the connection as well as the ecosystem of the relationship that unites customers with service that been delivered.

In another theoretical concept, Dabholkar ( 1990) exploratory study found that co-creation activities acknowledge the customer as a functioning player in the practice of utilization and quality generation and recognizes customer involvement as a co-creator of experience. Besides, the importance of interactions between customer-service providers in terms of value co-creation was explained by social exchange theory ( Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). The theory explains how co-created value for the customer develops with consumers which could raise relationships the consumer's loyalty and word of mouth in the sort of exclusive and personalized experiences. The result shapes the situation to draw a strong predictor of repetitive purchasing behavior ( Bolton, 2011). According to Cheng et al. ( 2013), firms that are focused on the customer are those that ensure continuous delivery of superior value throughout the relationship life-cycle by offering customized products and services to its customers.

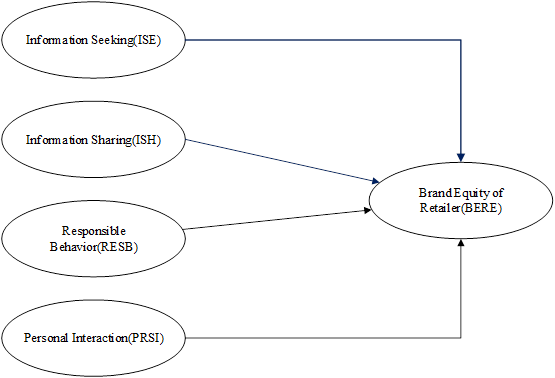

New ideas in relationship marketing research show that customers are no longer become passive entities in value-creating interaction, but they co-jointly creates the offering made by firms, co-creates the value, co-produce and co-innovate with firms ( Payne et al., 2008). Lemon et al. ( 2001) and Zaglia ( 2013) found that it is very helpful because it brings members closer together, exchanging ideas, developing mutual interests and increasing members’ affective connection towards the brand, and become crucial in brand selection. Even more, recent findings by Kristal et al. ( 2016) empirically found that co-creation has a beneficial impact on this new equity. Also, Millspaugh and Kent ( 2016) proposed that co-creation practices and positive interaction with customers lead to brand equity development of SME designer fashion enterprises. Based on the above discussion and findings, the following hypotheses are developed and Figure

H1: There is a positive relationship between Information seeking (ISE) and the brand equity of retailer (BERE)

H2: There is a positive relationship between Information sharing (ISH) and the brand equity of retailer (BERE)

H3: There is a positive relationship between Responsible behavior (RESB) and the brand equity of retailer (BERE)

H4: There is a positive relationship between Personal interaction (PRSI) and the brand equity of retailer (BERE)

Problem Statement

The challenges faced by SME enterprises includes accessibility problems to finance assistance ( Abdullah et al., 2009), inadequate working capital ( Ekanem & Wyer, 2007), deficiency of human capital, lack of access to technology and innovation infrastructure ( Dervitsiotis, 2003; Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010), non-conducive government policies and stiff business competition particularly with large retail organizations ( Saleh et al., 2008; Saleh & Ndubisi, 2006). According to scholars ( Farsi, & Toghraee, 2014; Van de Vrande et al., 2009), numerous studies carried out on SMEs’ strengths and weaknesses in innovation, which require the practice of innovation approach. Furthermore, the development of social media has also highlighted major changes on how SME retailers should be innovative and cooperative to interact with their customers ( Flavián et al., 2006). Prahalad and Ramaswamy ( 2000) proposed the idea of co-creation in the innovation field which is an extension of the experience marketing. Lusch et al. ( 2016) stated that this new phenomenon is led by the Service-Dominant Logic (S-D Logic) who focused on the effects of value co-creation of customers-service suppliers.

The value co-creation process can improve retailers’ brand equity as it nurtures a ‘win-win’ situation for both retailers and customers ( Zhang et al., 2015). It allows both retailers and customers to cooperatively contribute their skills and knowledge throughout service interactivity to obtain benefits ( Vargo & Lusch, 2004). Moreover, Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer ( 2012) believes that co-creation can influence the brand equity of SME retailers because of the practice of customer-company interaction in larger businesses might be less intense and require other communication tools as compared to small enterprise. By implementing co-creation practices in SMEs daily operation, it may improve the self-enhancement aspects of consumers.

Earlier studies on SMEs retailers' validity found that a lot of small retailers have a deficiency of competitive advantage because of a lack of significant resources ( Roslin & Melewar, 2008). But simultaneously SMEs have the behavioral advantages of versatility, agile to change and decision making ( Dominguez & Mayrhofer, 2017; Nieto & Santamaría, 2010). Therefore, retailers need to leverage on these advantages to strengthen their brand equity which can be cultivated through relationship marketing efforts, instilling of brand knowledge into customers’ minds and creating of memorable service values ( Zhang et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2017). Several past studies linked to small businesses have analyzed external networks at the creation process ( Nieto & Santamaría, 2010) and reveal that smaller firms may gain from learning from the partner in new product applications. But research on what SMEs may fortify their new equity through value-creation with clients is still scarce ( BarNir & Smith, 2002; McGee et al., 1995). Thus, this research further concentrates on the value co-creation practices among SMEs retailers in brand building strategy as suggested by many scholars ( France et al., 2015; Ramaswamy & Ozcan, 2016).

Retailer’s branding and its relationship with the co-creation process is an emerging and significant focus area in current relationship marketing thinking ( Ramaswamy & Ozcan, 2016). This new interest is based on the argument that involving customers in the value creation process. According to Keller et al. ( 2008) and Vargo et al. ( 2008) brand building strategy is an important source of brand equity and customers have played their roles by integrating resources for the production of valuable output.

Various attempts also have been made to explore the brand co-creation concept and its major impact from the perspective of strategic marketing studies ( France et al., 2015; Ramaswamy & Ozcan, 2016; Shao & Ross, 2015) and management issues ( Ind, 2014). However, Fisher and Smith ( 2011) argue that there is no concrete evidence that co-creation will result in a satisfactory outcome to the brand or company as it could lead to a chaotic situation. The inconsistency of findings has led marketing and management scholars to explore how to effectively implement, manage and strategize the co-creation process in building brand strength which will improve the overall brand equity of retailers. The role of co-creation and its impact on retailer brand equity has not been studied appropriately, notably in the service industries among SMEs.

H1: There is a positive relationship between Information seeking (ISE) and the brand equity of retailer (BERE)

H2: There is a positive relationship between Information sharing (ISH) and the brand equity of retailer (BERE)

H3: There is a positive relationship between Responsible behavior (RESB) and the brand equity of retailer (BERE)

H4: There is a positive relationship between Personal interaction (PRSI) and the brand equity of retailer (BERE)

Research Questions

The current study attempts to answer the following research question;

Does information seeking (ISE) positively influence the brand equity of retailer (BERE)?

Does information sharing (ISH) positively influence the brand equity of retailer (BERE)?

Does responsible behaviour (RESB) positively influence the brand equity of retailer (BERE)?

Does personal interaction (PRSI) positively influence the brand equity of retailer (BERE)?

Purpose of the Study

This study aims to advance our understanding regarding the function of customer value co-creation in influencing the retailer’s brand equity. Hence, this study employed customer citizenship behavior ( Yi et al., 2011) which consists of four elements: information seeking (ISE), information sharing (ISH), responsible behaviour (RESB) and personal interaction (PRSI).

Research Methods

Sampling design and procedures

The current study collected data from the customers of SME at selected business complexes. The location of this study conducted in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. All retailers involved in this study have received various supports under entrepreneurial development programs such as financial facilities, business consultations, and marketing grants. The data was collected using purposive sampling and personal administered questionnaires. The drop and collect technique were applied to distribute the questionnaires. Under the collect and drop procedure, the investigators and the survey were delivered by the field advocates that are trained directly to managers or the owner of the tailoring shops. Subsequently, the questionnaire was distributed to the customers at the business premises. The questionnaires were then distributed to the customers. Out of 650 copies of questionnaires that were disseminated, 548 respondents (84%) successfully returned the survey questionnaire.

Research instruments

The survey questions were adopted and adapted from past studies. The customer participation behavior was operationalized as a multidimensional construct which consists of four major dimensions including (1) information seeking (ISE), (2) information sharing (ISH), (3) responsible behaviour (RESB) and (4) personal interaction (PRSI). The items of the constructs were adapted from the research by Yi and Gong ( 2008) and Yi et al. ( 2011). In accordance with past research, the new equity has been quantified as a unidimensional construct which is measured by adapting the items from Gil-Saura et al. ( 2013). These items were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1"strongly disagree" to 5 "strongly agree".

Common method bias (CMB)

Previous researchers argued that CMB could possibly influence behavioral research results due to the gathering of cross-sectional data from a single respondent (customer of tailoring services) by means of the same questionnaire set ( Podsakoff et al., 2003). To address this issue, a number of procedural remedies have been anticipated during the research design process. Besides that, the researchers had also undertaken statistical remedies to check the common method bias ( Podsakoff et al., 2003). Another statistical remedy to check the existence of CMB is using Harman’s single-factor analysis. The result of 34.2%, for the first factor, was not contributing towards CMB. Besides, the correlations between constructs measured in the correlation matrix were evaluated ( Bagozzi et al., 1991). As suggested by Kim et al. ( 2013), strong evidence of the CMB exists if any of the correlations are higher than the value of 0.90. Therefore, the results indicated that CMB is not likely to compromise the findings of the study (refer to Table

Findings

Among the participants, most of the respondents (548) were male (52 percent). 164 (30 percent) is in the category of 20-29 years, 188 (34 percent) within the age of 30-39 years and, 105 (19%) are age 40-49 years old. 85% of the respondents are Malay and 272 respondents are married with at least one child, which is 49.7 percent of the total participant of this survey. 27.7% and 19% of the respondents have a monthly income bracket between RM2, 000 to RM3, 999, and RM4,000 to RM5,999 respectively. The majority of the customer (42 percent) possess a relationship with the service provider for at least one to two years.

Measurement model analysis

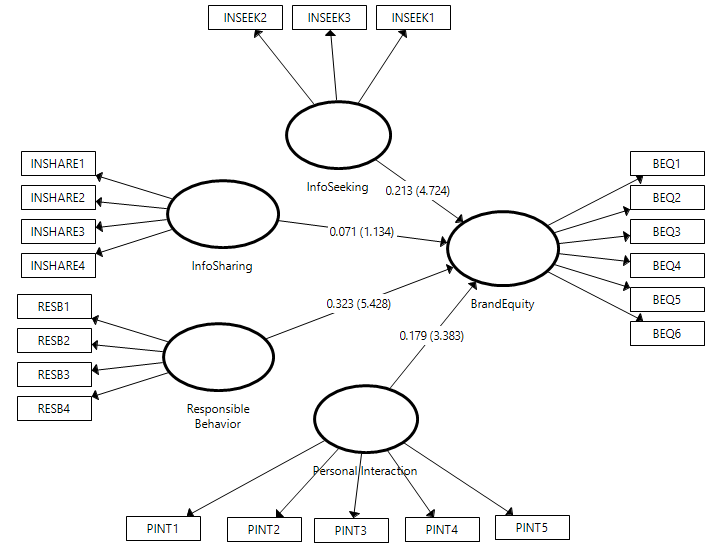

Following early researchers suggestion, the reliability and validity of the constructs were examined by using Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), loadings, and average variance extracted (AVE) value ( Anderson & Gerbing 1988; Venkatesh et al., 2012). All the measurement was analyzed using Smart PLS 3.0 software.

The Cronbach alpha values were found to surpass the threshold value of 0.7 for the constructs, implying appropriate reliability ( Hair et al., 2017). Furthermore, the item loading of the constructs of this study was ranging from 0.712 to 0.913 which is over than the cut-off value 0.6 ( Chen & Myagmarsuren, 2011). As portrayed in Table

Structural model

The analysis calculated that inflation and also the endurance values, before analyzing the structural model. The results shows that the VIF (Variance Inflation Factors) values of all constructs were in the range of between 1.341 and 1.878 under the acceptable range as suggested by Venkatesh et al. ( 2012). Thus, the collinearity value among predictor constructs in this study is not an issue. After that, a procedure with 2, 000 samples has been implemented to check the importance of the path coefficients. The R 2 value for brand equity is 0.426 which is greater than the moderate value of 0.33 ( Hair et al., 2017); thus, the model demonstrates a moderate explanatory power.

As proposed, information seeking (β = 0.213, t = 4.724, p < 0.05), positively influenced SME brand equity; thus H1 is supported. Moreover, the results indicate that responsible behavior (β = 0.323, t = 5.428, p < 0.05), and personal interaction (β = 0.179, t = 3.383, p < 0.05) have significant positive effects on SME brand equity. As this study concludes, H3 and H4 are accepted. The findings indicate that all the exogenous variables jointly explained 42.6% of the variance in brand equity (refer to Figure

Conclusion

The current study aspires to address the impact of customer participation behavior on SME brand equity. The positive association of customer participation and brand equity in support of prior studies such as work by Ramaswamy and Ozcan ( 2016) and Merrilees ( 2016). Returning into the hypotheses, Table

Study limitations and future research

Regardless of the stimulating discoveries of the present study, there are several constraints need to address. First, the sample size of the analysis is reduced to 548 participants due to resource constraints. Secondly, as the reach of the analysis is confined to SME clients in Kuala Lumpur, the positioning of the study is bound by Kuala Lumpur and might not reflect the whole population. Third, this study only focusses on customer participation behavior, therefore, this research can be extended by (1) extending the model through the incorporation of different types of variables such as personality traits, customer citizenship behavior, as well as moderating variables such as relationship duration, to provide a more exhaustive model on SME brand equity.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a research project supported by Fundamental Research Grant Scheme, grant number: FRGS/1/2018/SS03/UKM/02/8.

References

- Abdullah, Z., Ahsan, N., & Alam, S. S. (2009). The effect of human resource management practices on business performance among private companies in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(6), 65-72.

- Ahmad, S. Z., Abdul Rani, N. S., & Mohd Kassim, S. K. (2010). Business challenges and strategies for development of small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia. International Journal of Business Competition and Growth, 1(2), 177-197.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411-423.

- Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421-458.

- BarNir, A., & Smith, K. A. (2002). Interfirm alliances in the small business: The role of social networks. Journal of small Business Management, 40(3), 219-232.

- Bendapudi, N., & Leone, R. P. (2003). Psychological implications of customer participation in co-production. Journal of Marketing, 67(1), 14-28.

- Bitner, M. J., Faranda, W. T., Hubbert, A. R., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1997). Customer contributions and roles in service delivery. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(3), 193-205.

- Bolton, R. N. (2011). Customer engagement: Opportunities and challenges for organizations. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 272-274.

- Cambra-Fierro, J., Melero-Polo, I., & Vázquez-Carrasco, R. (2014). The role of frontline employees in customer engagement. Revista Española de Investigación de Marketing ESIC, 18(2), 67-77.

- Chen, C. F., & Myagmarsuren, O. (2011). Brand equity, relationship quality, relationship value, and customer loyalty: Evidence from the telecommunications services. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 22(9), 957-974.

- Cheng, C. F., Chang, M. L., & Li, C. S. (2013). Configural paths to successful product innovation. Journal of Business Research, 66(12), 2561-2573.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cossío-Silva, F. J., Revilla-Camacho, M. Á., Vega-Vázquez, M., & Palacios-Florencio, B. (2016). Value co-creation and customer loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1621-1625.

- Dabholkar, P. (1990). How to improve perceived quality by improving customer participation. In B. J. Dunlap (Ed.), Developments in marketing science (pp. 483-487). Springer.

- Dervitsiotis, K.N. (2003). Beyond stakeholder satisfaction: Aiming for a new frontier of sustainable stakeholder trust. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 14(5), 515-528.

- Dominguez, N., & Mayrhofer, U. (2017). Internationalization stages of traditional SMEs: Increasing, decreasing and re-increasing commitment to foreign markets. International Business Review, 26(6), 1051-1063.

- Ekanem, I., & Wyer, P. (2007). A fresh start and the learning experience of ethnic minority entrepreneurs. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(2), 144-151.

- Farsi, J. Y., & Toghraee, M.T. (2014). Identification the main challenges of small and medium sized enterprises in exploiting of innovative opportunities: Case study Iran SMEs. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 4(4), 1-15.

- Fisher, D., & Smith, S. (2011). Co-creation is chaotic: What it means for marketing when no one has control. Marketing Theory, 11(3), 325-350.

- Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M., & Gurrea, R. (2006). The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Information & Management, 43(1), 1-14.

- France, C., Merrilees, B., & Miller, D. (2015). Customer brand co-creation: A conceptual model. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(6), 848-864.

- Fuat Firat, A., Dholakia, N., & Venkatesh, A. (1995). Marketing in a postmodern world. European Journal of Marketing, 29(1), 40-56.

- Gil-Saura, I., Ruiz-Molina, M. E., Michel, G., & Corraliza-Zapata, A. (2013). Retail brand equity: A model based on its dimensions and effects. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 23(2), 111-136.

- Grissemann, U. S., & Stokburger-Sauer, N. E. (2012). Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1483-1492.

- Hair Jr, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135.

- Ind, N. (2014). How participation is changing the practice of managing brands. Journal of Brand Management, 21(9), 734-742.

- Johnson, J. W. (1996). Linking employee perceptions of service climate to customer satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 49(4), 831-851.

- Keller, K. L., Apéria, T., & Georgson, M. (2008). Strategic brand management: A European perspective. Pearson Education.

- Kelley, S. W., Donnelly Jr, J. H., & Skinner, S. J. (1990). Customer participation in service production and delivery. Journal of Retailing, 66(3), 315-335.

- Kim, Y. H., Kim, D. J., & Wachter, K. (2013). A study of mobile user engagement (MoEN): Engagement motivations, perceived value, satisfaction, and continued engagement intention. Decision Support Systems, 56, 361-370.

- Kristal, S., Baumgarth, C., Behnke, C., & Henseler, J. (2016). Is co-creation really a booster for brand equity? The role of co-creation in observer-based brand equity (OBBE). Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(3), 247-261.

- Kristensson, P., Matthing, J., & Johansson, N. (2008). Key strategies for the successful involvement of customers in the co-creation of new technology-based services. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 19(4), 474-491.

- Lafley, A. G., & Charan, R. (2008). The Game-Changer: How You Can Drive Revenue and Profit Growth with Innovation. Random House LLC.

- Lemon, K. N., Rust, R. T., & Zeithaml, V. A. (2001). What drives customer equity?. Marketing Management, 10(1), 20-25.

- Linnenluecke, M.K., & Griffiths, A. (2010). Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. Journal of World Business, 45(4), 357-366.

- Lusch, R. F., Vargo, S. L., & O’Brien, M. (2007). Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. Journal of Retailing, 83(1), 5-18.

- Lusch, R.F., Vargo, S.L., & Gustafsson, A. (2016). Fostering a trans-disciplinary perspectives of service ecosystems. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2957-2963.

- Matthing, J., Sanden, B., & Edvardsson, B. (2004). New service development: Learning from and with customers. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(5), 479-98.

- McGee, J. E., Dowling, M. J., & Megginson, W. L. (1995). Cooperative strategy and new venture performance: The role of business strategy and management experience. Strategic Management Journal, 16(7), 565-580.

- Merrilees, B. (2016). Interactive brand experience pathways to customer-brand engagement and value co-creation. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(5), 402-408.

- Millspaugh, J.E.S., & Kent, A. (2016). Co-creation and the development of SME designer fashion enterprises. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 20(3), 322-338.

- Nieto, M. J., & Santamaría, L. (2010). Technological collaboration: Bridging the innovation gap between small and large firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(1), 44-69.

- Oláh, J., Zéman, Z., Balogh, I., & Popp, J. (2018). Future challenges and areas of development for supply chain management. LogForum, 14(1), 127-138. https://doi.org/10.17270/J.LOG.2018.238

- Payne, A.F., Storbacka, K., & Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 83-96.

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business Press.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 879-903.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2000). Co-opting customer competence. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 79-90.

- Ramaswamy, V., & Ozcan, K. (2016). Brand value co-creation in a digitalized world: An integrative framework and research implications. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 33(1), 93-106.

- Roslin, R. M., & Melewar, T. C. (2008). Hypermarkets and the small retailers in Malaysia: Exploring retailers' competitive abilities. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 9(4), 329-343.

- Saleh, A. S., & Ndubisi, N. O. (2006). SME development in Malaysia: Domestic and global challenges. University of Wollongong Economics Working Paper Series 2006.

- Saleh, A. S., Caputi, P., & Harvie, C. (2008). Perceptions of business challenges facing Malaysian SMEs: Some preliminary results. In M. Obayashi & N. Oguchi (Eds.), 5th SMEs in a Global Economy Conference 2008 (pp. 79-106). University of Wollongong.

- Shamim, A., Ghazali, Z., Jamak, A., & Sedek, A. B. (2015). Extrinsic experiential value as an antecedent of customer citizenship behavior. In Technology Management and Emerging Technologies (ISTMET), 2015 International Symposium (pp. 202-206). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISTMET.2015.7359029

- Shao, W., & Ross, M. (2015). Testing a conceptual model of Facebook brand page communities. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 9(3), 239-258.

- Shaw, G., Bailey, A., & Williams, A. (2011). Aspects of service-dominant logic and its implications for tourism management: Examples from the hotel industry. Tourism Management, 32(2), 207-214.

- SME Corporation Malaysia. (2012). SME Masterplan 2012-2020. Kuala Lumpur.

- SME Corporation Malaysia. (2014). SME Corp Malaysia Annual Report. Kuala Lumpur.

- Thibaut, J. W., & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. Wiley.

- Van de Vrande, V., De Jong, J. P., Vanhaverbeke, W., & De Rochemont, M. (2009). Open innovation in SMEs: Trends, motives and management challenges. Technovation, 29(6), 423-437.

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1-17.

- Vargo, S. L., Maglio, P. P. & Akaka, M. A. (2008). On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. European Management Journal, 26(3), 145-152.

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157-178.

- Yi, Y., & Gong, T. (2008). If employees “go the extra mile,” do customers reciprocate with similar behavior?. Psychology & Marketing, 25(10), 961-986.

- Yi Y., & Gong, T. (2013). Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research, 66(9), 1279–1284.

- Yi Y., Nataraajan, R., & Gong, T. (2011). Customer participation and citizenship behavioural influences on employee performance, satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention. Journal of Business Research, 64(1), 87–95.

- Zaglia, M. E. (2013). Brand communities embedded in social networks. Journal of Business Research, 66(2), 216-223.

- Zhang, M., Guo, L., Hu, M., & Liu, W. (2017). Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: Mediating effect of customer value creation. International Journal of Information Management, 37(3), 229-240.

- Zhang, J., Jiang, Y., Shabbir, R., & Du, M. (2015). Building industrial brand equity by leveraging firm capabilities and co-creating value with customers. Industrial Marketing Management, 51, 47-58.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

06 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-087-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

88

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1099

Subjects

Finance, business, innovation, entrepreneurship, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues

Cite this article as:

Mohd Anim, N. A. H., Omar, N. A., Kassim, A. S., Nazri, M. A., & Jannat, T. (2020). The Role Of Consumers Participation Behavior To Smes Brand Equity. In Z. Ahmad (Ed.), Progressing Beyond and Better: Leading Businesses for a Sustainable Future, vol 88. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 377-389). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.33