Abstract

This article presents study results of adolescents attitudes related to violence (in relation to psychological, physical violence, cyberbullying, spoilage and encroachment on other people's things). This article describes gender specificity of attitudes towards violence. The study sample included 64 adolescents aged 14-17, including 35 girls and 29 boys. The main method that was used is the author’s questionnaire, which includes 36 questions forming 5 scales: attitudes toward physical abuse, attitudes toward psychological abuse, attitudes toward spoilage, assault on other people's things, attitudes towards cyberbullying and alternative individual norms for violence. Positive attitudes were found in relation to psychological, physical violence, corruption, assault on other people's things, cyberbullying, while significant gender differences were mainly identified in relation to psychological and physical violence, as well as on the “cyberbullying” scale. The article provides data that allow us to argue that the structure of attitudes is gender specific. It is also proven that the structure of attitudes towards violence in girls is characterized by a closer interconnection of components. A greater number of significant correlations were found in the structure of girls' attitudes towards violence: attitudes toward physical violence were significantly correlated with attitudes toward psychological violence, attitudes toward damage to other people's things.

Keywords: Attitudesviolenceteenagerpersonalityinterpersonal relationships

Introduction

The violence remains a common phenomenon in various areas of social relations today, manifesting itself at various levels of social organization, such as: the state level, the level of large and small social groups and the level of interpersonal communication. The institutional form of violence is reflected at the state level in form of military violence and punishment of criminals. The structural violence at the intergroup level manifests itself in form of racial, age, gender, economic and other forms of discrimination. Emergence of nuclear weapons and modern space rocket delivery vehicles, development of bacteriological and chemical weapons determines the threat of military violence, both regionally and globally. The active spreading and manifestation of violence in society is provided by existing system of values which relies to status, property, age relations, and creates the basis for pronounced social tension. The problem of violence is especially acute in industrialized countries. So, to study various forms of violence in world science in the second half of the 20th century, a separate discipline was formed - the science of violence.

Direct violence is common in various areas of interpersonal interaction, such as: parent-child relationships as well as relations between siblings, between students, in a boss-subordinate relationship, etc. According to a survey conducted in Russia by Soldatova in 2016 every second child among thousands of children in educational institutions from 7 to 12 years old facing aggressive behavior and clearly defines it, and approximately every fourth child from 7 to 9 years old and every third child from 10 to 12 years old facing violence in school (Soldatova et al., 2017).

The problem of bullying has been studied for a long time in world psychology, and therefore it has a large amount of accumulated theoretical and practical knowledge (Olweus & Limber, 2010; Wolke & Lereya, 2015). Traditionally studied such phenomena as the prevalence of bullying in the environment (Olweus & Limber, 2010), roles of participants in a bullying situation (e Silva et al., 2019), the interrelation between bullying experiences and self-destructive behavior (Tang et al., 2020). The key question is the search for causes of manifestation and experiencing bullying situations. Researchers emphasize the importance of studying individual-personality characteristics of bullying participants. There are internal prerequisites that contribute to the fact that a person most actively masters a certain role in a bullying situation (e Silva et al., 2019; Olweus & Limber, 2010). The importance of understanding the social context of bullying is emphasized at the same time: domestic violence, hyperprotection, reinforcing the helplessness of a child; family abuse (Tang et al., 2020), the influence of television, of the Internet, and the media (Fitzpatrick et al., 2019). With spreading of the Internet, a new form of bullying has appeared (“cyberbullying”, “cybermobbing”, bullying using modern technologies) (Caravita et al., 2016). The process of socialization of adolescents is largely moving to the Internet (Soldatova et al., 2017). The influence from the virtual space cannot remain without a trace for a teenager (Wachs et al., 2016) A review of world studies suggests the phenomenon of “Youth Violence” (De Ribera et al., 2019). It is noted that “youth violence is a complex social problem,” including violence between coevals, as well as between dating partners, and between groups (Davidson & Canivez, 2012). Thus, a number of risk factors for violence among young people have been described in foreign literature and include a history of violent victimization (Latham et al., 2019), antisocial beliefs and attitudes, exposure to violence and conflict in the family and society (Farrington et al., 2017).

It is widely recognized that a system of values and beliefs are important factors in individual behavior (Maimone et al., 2018). Studies have shown that positive attitudes of parents regarding the physical punishment of children are a significant predictor of its use (Jakešová & Slezáková, 2016). Attitudes to violent crime and punishments have important consequents for public policy in crime control (Prechathamwong & Rujiprak, 2018). Observation of violence leads to the assimilation of aggressive attitudes and the reproduction of aggressive behavior. A person raised up by parents who have a positive attitude and practice physical punishment is more likely to support harsh punishment and often shows aggressive behavior in society (Jakešová & Slezáková, 2016). Analysis of English-language literature reflects the wide interest of scientists in the formation of values and attitudes (in relation to life, health, power, environment, school) in childhood and adolescence, considering the sensitivity of this period in terms of exposure to influences from the family, peer, and the media (Shevlin & Goodwin, 2019).

Problem Statement

The widespread manifestation of violence and the positive attitude towards it, the broadcasting of violence in the media and the Internet, the high popularity of computer-based aggressive games along with the increasing infantilization, certainly sets new standards for communication between people in which normativity of violence, addiction and tolerance to violence becomes acceptable. Described trends determine the need for a careful study of the content of social attitudes regarding the violence of modern youth. However, there is no description of a comprehensive theoretical model explaining the classification and grouping of attitudes to the manifestation of violence today, and there are insufficient studies aimed at understanding the interrelation between the choice of violent behavior and personality traits (Cavalcanti & Pimentel, 2016). Social attitudes are one of the most popular constructs used to describe determinants of human behavior in social situations. Attitude has a regulatory and organizing influence on the mental processes of the individual and his emotional state, and also sets a certain tendency for the individual to behave in the corresponding situation. The insufficient development of the problem of attitudes in relation to violence necessitates a theoretical and empirical development of the problem, the development of Russian-language tools aimed at diagnosing attitudes of adolescents to manifesting violence in social spheres.

Research Questions

How the attitudes towards violence in adolescent girls and boys are expressed? What is the difference between gender attitudes towards violence among teenagers? How adolescent attitudes towards physical and psychological abuse are expressed? Is there a relationship between adolescent attitudes towards physical and psychological violence, attitudes toward spoilage, assault on other people's things, attitudes towards cyberbullying?

Purpose of the Study

We attempted to identify and describe gender characteristics of attitudes of adolescents in relation to violence in our own study. The aim of our study is to determine the severity of attitudes toward physical abuse, attitudes toward psychological abuse, attitudes toward spoilage, assault on other people's things, attitudes towards cyberbullying and alternative individual norms for violence.

Research Methods

The author’s questionnaire was created by the attitudes for the purpose of diagnosis. The questionnaire includes 36 questions that form 5 scales: attitudes towards physical abuse, attitudes towards psychological abuse, attitudes towards spoilage, assault on other people's things, attitudes towards cyberbullying, as well as individual norms for alternatives to violence. The sample totaled 64 people, among them 35 female adolescents and 29 male adolescents. The selection criterion was the age of 14-17 years. We used the calculation of arithmetic means (M), Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test, Mann-Whitney U test, t-test for independent samples, and Spearman rank order correlation in statistical processing of the obtained empirical data.

Findings

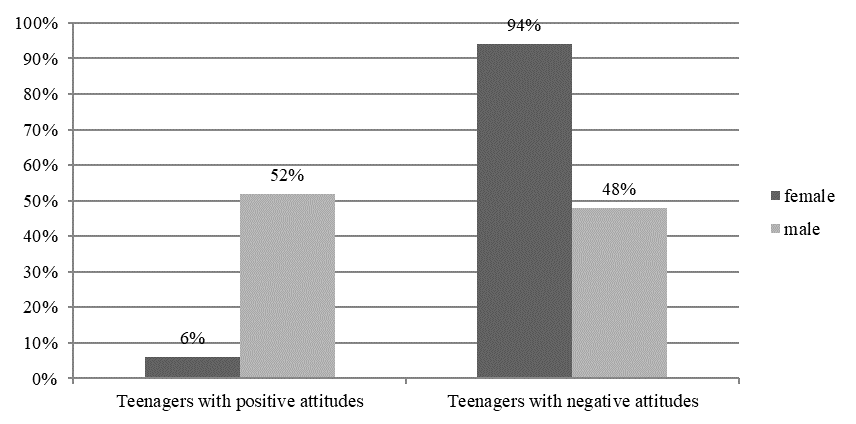

The sample of adolescents is divided into two groups at the first stage of the study. The first group consists of adolescents with positive attitudes towards violence. This group includes adolescents who received more than half of the maximum possible points on such scales as attitudes towards physical abuse, attitudes towards psychological abuse, attitudes toward damaging, abusing of other people's things and attitudes towards cyberbullying. The second group included adolescents with negative attitudes towards violence (figure

52 % of boys have positive attitudes towards violence, 94 % of girls have negative attitudes towards violence according to figure

A more detailed description of attitudes regarding the manifestation of various forms of violence is of special research interest for us, as it allows us to understand the specificity of the formation of attitudes in relation to violence (table

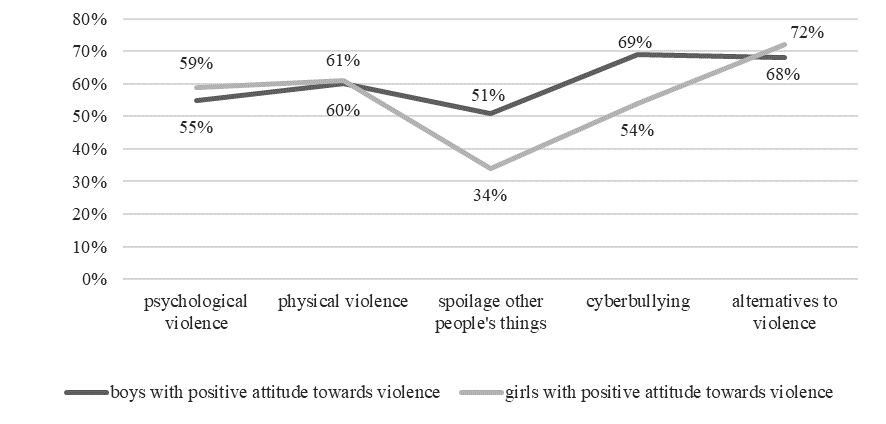

The table

So, a difference was found between boys and girls with positive attitudes towards violence at the level of the statistical trend in attitudes towards cyberbullying (U = 4.000, p ≤ 0.1). The acquired data is consistent with other studies: boys tend to be cyberbullying aggressors, while girls are more likely to be victims of cyberbullying (Dehue et al., 2008; Walrave & Heirman, 2010). It can be assumed that boys with positive attitudes towards violence are more willing to use cyberbullying due to better adaptation to the global network, a lot of time for participation, and a passion for online games.

Correlation analysis revealed the structure of attitudes towards violence of boys and girls in adolescence. A great number of differences were found at the level of the number of significant relationships. A greater number of significant correlations were found in the structure of girls' attitudes towards violence: attitudes toward physical violence were significantly correlated with attitudes toward psychological violence (r = 0.414, p ≤ 0.05), attitudes towards damage to other people's things (r = 0.439, p ≤ 0.01). The girls' attitudes towards individual norms for alternatives to violence have a significant inverse relationship with attitudes towards the destruction of other people's things (r = - 0.404, p ≤ 0.05), attitudes towards physical violence (r = - 0.35, p ≤ 0.05), and attitudes towards psychological violence (r = - 0.347, p ≤ 0.05). Preparedness for physical forms of violence (fights, blows) in girls is combined with a willingness to verbal threats, screaming and damaging things. A negative attitude to these forms of violence forms a constructive interaction with coevals (the ability to listen to and understand someone else's point of view, regulate their emotions, and ability to resolve conflicts peacefully). The structure of the attitudes of the boys revealed one significant correlation relationship: the less pronounced the attitude towards cyberbullying, the more pronounced are the individual norms for alternatives to violence (r = - 0.374, p ≤ 0.05). The formation of behavior standards in the social matrixes in the Internet reveals itself in the form of boys' readiness for abusive comments, using and sharing other people's photos, belittling the dignity of another person in a chat is combined with their impulsiveness, inability to negotiate, sharp reaction to gossip, inability to admit their mistakes and ask for forgiveness.

Conclusion

This research project contributes to the literature on teenager's attitudes related to violence by assessing attitudes to psychological, physical violence, cyberbullying, spoilage and encroachment on other people's things. Based on teenage self-reports data were collected about gender differences in attitudes towards violence.

Girls with positive attitudes toward violence have attitudes toward psychological abuse (U = 3.000, p ≤ 0.05) and attitudes toward physical violence (U = 1.500, p ≤ 0.01).

Boys with positive attitudes towards violence are characterized by positive attitudes towards physical violence (t = 3.538, p ≤ 0.001), towards cyberbullying (t = 2.538, p ≤ 0.05), and psychological abuse (t = 2.321, p ≤ 0.05).

The structure of attitudes is gender specific. A greater number of significant correlations were found in the structure of girls' attitudes towards violence: attitudes toward physical violence were significantly correlated with attitudes toward psychological violence (r = 0.414, p ≤ 0.05), attitudes toward damage to other people's things (r = 0.439, p ≤ 0.01).

References

- Caravita, S. C. S., Colombo, B., Stefanelli, S., & Zigliani, R. (2016). Emotional, psychophysiological and behavioral responses elicited by the exposition to cyberbullying situations: Two experimental studies. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 49-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.02.003

- Cavalcanti, J. G., & Pimentel, C. E. (2016). Personality and aggression: A contribution of the General Aggression Model. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 33(3), 443-451. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02752016000300008

- Davidson, M. M., & Canivez, G. L. (2012). Attitudes Toward Violence Scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(18), 3660-3682. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512447578

- De Ribera, O. S., Trajtenberg, N., Shenderovich, Y., & Murray, J. (2019). Correlates of youth violence in low- and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 49, 101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.07.001

- Dehue, F., Bolmon, C., & Vollink, T. (2008). Cyberbullying: youngsters’ experiences and parental perception. Cyber Psychology & Behavior, 11(2), 217-223. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0008

- e Silva, G. R. R., de Lima, M. L. C., Barreira, A. K., & Acioli, R. M. L. (2019). Prevalence and factors associated with bullying: differences between the roles of bullies and victims of bullying. Journal de Pediatria. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2019.09.005

- Farrington, D. P., Gaffney, H., & Ttofi, M. M. (2017). Systematic reviews of explanatory risk factors for violence, offending, and delinquency. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 24-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.11.004

- Fitzpatrick, C., Burkhalter, R., & Asbridge, M. (2019). Adolescent media use and its association to wellbeing in a Canadian national sample. Preventive Medicine Reports, 14, 100867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100867

- Hoover, J., & Olsen, G. (2001). Teasing and harassment: The frames and scripts approach for teachers and parents. Solution Tree.

- Jakešová, J., & Slezáková, S. (2016). Rewards and Punishments in the Education of Preschool Children. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 217, 322-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.02.095

- Latham, R. M., Meehan, A. J., Arseneault, L., Stahl, D., Danese, A., & Fisher, H. L. (2019). Development of an individualized risk calculator for poor functioning in young people victimized during childhood: A longitudinal cohort study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104188

- Maimone, R., Guerini, M., Dragoni, M., Bailoni, T., & Eccher, C. (2018). PerKApp: A general purpose persuasion architecture for healthy lifestyles. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 82, 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2018.04.010

- Nabuzoka, D. (2003). Teacher ratings and peer nominations of bullying and other behaviour of children with and without learning difficulties. Educational Psychology, 23(3), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341032000060147

- Olweus, D., & Limber, S. P. (2010). Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(1), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x

- Pellegrini, A. D., & Bartini, M. (2000). A longitudinal study of bullying, victimization, and peer affiliation during the transition from primary school to middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 37(3), 699–725. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312037003699

- Prechathamwong, W., & Rujiprak, V. (2018). Causal model of fear of crime among people in Bangkok. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2018.01.009

- Shevlin, B. R. K., & Goodwin, K. A. (2019). Past behavior and the decision to text while driving among young adults. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 60, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.09.027

- Soldatova, G. U., Rasskazova, E. I., & Nestik, T. A. (2017). T͡Sifrovoe pokolenie Rossii: kompetentnostʹ i bezopasnostʹ [The digital generation of Russia: competence and security]. Smysl Moskva.

- Tang, J. J., Yu, Y., Wilcox, H. C., Kang, C., Wang, K., Wang, C., Wu, Y., & Chen, R. (2020). Global risks of suicidal behaviours and being bullied and their association in adolescents: School-based health survey in 83 countries. EClinicalMedicine, 19, 100253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.100253

- Wachs, S., Jiskrova, G. K., Vazsonyi, A. T., Wolf, K. D., & Junger, M. (2016). A cross-national study of direct and indirect effects of cyberbullying on cybergrooming victimization via self-esteem. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.01.002

- Walrave, M., & Heirman, W. (2010). Cyberbullying: predicting victimisation and perpetration. Children & Society, 25(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00260.x

- Wolke, D., & Lereya, S. T. (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(9), 879–885. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306667

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

26 October 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-090-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

91

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-340

Subjects

Self-regulation, personal resources, educational goals, professional goals, mental health, digitalization

Cite this article as:

Dementiy, L. I., Kupchenko, V. E., & Fourmanov, I. A. (2020). Teenager’s Gender Attitudes Regarding Violence. In V. I. Morosanova, T. N. Banshchikova, & M. L. Sokolovskii (Eds.), Personal and Regulatory Resources in Achieving Educational and Professional Goals in the Digital Age, vol 91. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 42-49). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.04.6