Abstract

Family-centered therapy is described as a rather controversial approach and sometimes difficult to implement because of its philosophy of recognizing and respecting the family as an equal partner in the entire therapeutic process with specialists, but there are situations when this approach is not viable either due to the absence of parents from the lives of children, or due the lack of interest from them. Through this study, carried out over a period of 4 years, we decided to investigate the effectiveness of two models of therapy approach, respectively specialist-centered therapy vs. family-centered therapy, from the point of view of the development of the children with nonverbal ASD, on these five areas: social, cognitive, language, personal autonomy, and motor. The results revealed the fact that family-centered therapy is more effective, with significant differences in the acquisition of the social, cognitive, motor spheres and also in the children's mental age evolution, and less effective and with insignificant differences, in the areas of language development and personal autonomy, where the results were more relevant in the case of specialist-centered therapy. Also, regardless of the therapeutic approach model, all 6 children included in the study presented a disharmonious profile during the intervention, the most significant deficiencies being observed in the sphere of communication and language skills.

Keywords: Family-centered therapy/practiceexpert-centered practice/therapyautism spectrum disordersnon-verbaldevelopment profile

Introduction

Family-centered therapy is described as a rather controversial approach and sometimes difficult to implement because of its philosophy, of recognizing and respecting the family as an equal partner with the specialists, in the whole therapeutic process. This involves investing family members with active roles in the process of evaluating and implementing the intervention, where both parents and professionals are seen as equal partners (Brewer, McPherson, Magrab, & Hutchin, 1989). Based on these considerations, family-centered practice does not only mean establishing a trusting relationship between the specialist and the parent, but also the existence of a balance of power in decision-making, mutual respect and honesty (Keen, 2007).

References to family-centered practice begin to emerge around the 1950s, but interest in this approach manifests around the 1970s-1980s. In the conclusions of his study, Bronfenbrenner (1975) emphasized the impact of family involvement on children's development and implicitly their performance. The interest in this approach is gradually increasing, because by the end of the 1980s, ACCH (Association for Child Health Care) mentioned the basic elements of this approach in the intervention of children with special needs (Shelton, Jeppson, & Johnson, 1987).

During this period, experts in the field have developed several models in approaching family-centered practice, models that are part of a continuum regarding assuming the roles of expertise and decision-making power at the intervention level (Dunst, Johanson, Trivette, & Hamby, 1991). In this framework, we talk about Professionally-centered model, Family-allied model, Family-focused model, Family-centered model (Dunst, Johanson, Trivette, & Hamby, 1991; Spe-Scherwindt, 2008). If in the Professionally-centered model, the decision-making power in the selection and implementation of the intervention activity is in the hands of the specialists, the role of the parents being minimal, both in terms of involvement and in establishing the deployment framework and the resources needed to perform the therapy, in the Family-centered model, parents and specialists become equal partners, the intervention being individualized to the needs of the child and the family, flexible, parents having a decisive role in the final decisions. Thus, by recognizing that the family is a constant in the child's life, the family-centered practice focuses on the interpersonal relationship between parents and the professional, who, together, identifies the most appropriate means to meet the child's needs starting from his / her acquisitions and strengths (O’Neil, Palisano, & Westcott, 2001).

The family-centered practice is based on three basic elements: (1) the emphasis placed on the strengths, interests and acquisitions of the child and not on his deficits; (2) equipping the family with decision-making power and control over the intervention activity; and (3) developing a close collaborative relationship between parents and professionals. To specialists, this paradigm shift was and is a real challenge, simply because they have to replace the role of decision-maker, coordinator, organizer, counselor, partner, facilitator and consultant in carrying out the intervention (Mikus, Benn, & Weatherston, 1994). According to Dunst, Trivette, and Hamby (2007), family-centered practice is a systematic way of creating a partnership with families, a partnership that involves (a) treating with dignity and respect, (b) respecting values and choices, and (c) giving support to strengthen and improve the functioning of the family environment.

Starting from these aspects it is surprising that the family-centered therapy has two major components: (1) the relational component based on a series of abilities such as active listening, empathy, trust in the other's potential, unconditional acceptance, respect, all necessary for professionals to build efficient, constructive and functional relationships with family members (Dempsey & Dunst, 2004; Dunst, Boyd, Trivette, & Hamby, 2002); and (2) participatory supportive practices, which are action / intervention oriented, including control and the distribution of roles. The specialists share information with the parents, analyze and discuss them on their side, encourage them to make informed and realistic decisions alone, use their knowledge, skills and competences to carry out the intervention, and the professionals help them acquire the new skills for the new therapy, and implicitly the progress of the child and the consolidation of a well-being at the family level (Dempsey & Dunst, 2004; Dunst et al., 2002; Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000).

The philosophy of family-centered practice has been adopted in a wide variety of areas of health, therapy, early intervention, special education (Murray & Mandell, 2006), and education (Stormshak, Dishion, Light, & Yasui, 2005).

The specialized literature places an increasing emphasis on the involvement of the family in the process of evaluation and early intervention, recognizing that the family is a constant in the life of the child, that it is part of a family unit, which in turn is part of a family, wider community (Crais & Calculator, 1998; Dunst, Johanson, Trivette, & Hamby, 1991; Iacono & Caithness, 2009). Beukelman and Mirenda (2005) underline the need for family involvement in the evaluation and intervention process for young children or with serious disabilities, to identify the problems with the team of specialists, to rank them, and to set intervention goals and strategies.

Problem Statement

There is ample evidence in the literature that (a) family-centered practice offers many proven benefits and positive outcomes for both children and their families (Dunst & Trivette, 2005; King, King, Rosenbaum, & Goffin, 1999; Trivette, Dunst, Boyd, & Hamby, 1995; Trivette, Dunst, & Hamby, 1996; Wilson, 2005), and (b) families are more satisfied and more involved in intervention than other existing models (Dempsey & Keen, 2008; Dunst et al., 2002; Espe-Scherwindt, 2008; King, King, Rosenbaum, & Goffin, 1999). However, the reality shows that there is a perception gap between professionals and family, the professionals being less focused on the family as a resource than they think, regardless of the category of persons with whom the intervention is carried out, and this is determined by the paradigm shift (Dunst, 2002). Thus, the paradigm shift is faced with a "slow adoption rate" being less used by professionals (Crais, Roy, & Free, 2006), even though comparative studies have surprised that specialist-focused programs rely less on relational practices (Dunst et al., 2002) and implicitly the results have less impact on the family and child (Dunst et al., 2002; Trute & Hiebert-Murphy, 2007) compared to family-focused practices.

Campbell and Halbert (2002) investigated this issue and overlooked the main reasons why family-centered practice was not very large. A first reason is the gap between the scientific world and practitioners, respectively they fail to keep up with all trends (Bruder, 2000; McWilliam, 1999). Another reason why specialists avoid this approach is the lack of proper and accurate training (Bailey, Aytch, Odom, Symons, & Wolery, 1999; Bruder, 2000; Gallagher, Malone, Cleghorne, & Helms, 1997) as well as the need to produce many time-consuming documents, much needed for intervention and collaboration with the family (O’Neil et al., 2001). Last but not least, the lack of support from the team of professionals (Murray & Mandell, 2006) regarding the partnership with the family, as well as the difficulty of perceiving the family as experts and equal members in the evaluation and intervention team (Affleck et al., 1989; Trivette, Dunst, Boyd, & Hamby, 1995) are barriers to the implementation of family-centered practice.

The efficiency of family-centered practice has been demonstrated in several program categories and with a wide variety of participants: from interventions in the medical field, early education, rehabilitation, education (Dunst, Trivette, & Hamby, 2007; Reich, Bickman, & Heflinger, 2004) to programs involving parents with intellectual disabilities (Wade, Mildon, & Matthews, 2007), parents with children of various ages (Dempsey and Dunst, 2004), parents with different socio-economic status (Law et al., 2003; Trivette et al., 1995; Trivette, Dunst, & Hamby, 1996) or from different cultures (Dempsey & Dunst, 2004).

In a meta-analysis by Dunst, Trivette, and Hamby (2006), which focused on 18 studies, it was surprising that family-centered practice has a strong impact on parents' beliefs about self-efficacy, positive perceptions of the program performance and outcomes, the behavior of the child and its evolution, as well as a greater confidence in his own parental abilities.

Dempsey and Keen (2008) found that this new paradigm correlates with a variety of child and family outcomes, consistent with the hypotheses of family-centered practice (Dunst, Trivette, & Hamby, 2007) as follows: (1) family centered practice reduces stress and increases well-being perceived by parents (King et al., 2003; Keen et al., 2010; O’Neil et al., 2001; van Schie et al., 2004); (2) parents develop parental skills (Dunst, Trivette, & Deal, 1988; Heller, Miller, & Hsieh, 1999); (3) the progress / evolution of the child (Mahoney & Bella, 1998; O’Neil et al., 2001) and especially when talking about early intervention (Dunst, 1999); (4) developing desirable behaviors in the children (Judge 1997); and (5) self-control (Dunst, Trivette, & LaPointe, 1994; Trivette, Dunst, Hamby, & LaPointe, 1996).

Research Questions

Q1. Will there be significant differences between the results obtained through the two approaches (specialist-centered practice vs. family-centered practice), regarding the performance of the child with ASD, in terms of acquisitions at the level of the developmental profile (social, cognitive, personal autonomy, motor skills)?

Purpose of the Study

In the present study we intend to comparatively analyze the efficiency of the practice focused on the specialist vs. family-centered practice in the therapeutic intervention of the children with ASD, setting the following objectives: (1) sampling the study participants on the 2 therapeutic approaches; (2) conducting the initial evaluation of the study participants (on the development profile components) according to the type of approach; (3) establishing and implementing the intervention program according to the approach; (4) reassessment of the performance of the study participants; (5) establishing the differences existing in the evolutionary process of the participants according to the type of approach and comparing the results.

Research Methods

Participants

The research was conducted with six children divided into two experimental samples, respectively sample 1, who benefited from family-centered therapy (Ef) and sample 2, who benefited from expert-centered therapy (Ee). The detailed presentation of the participants' samples can be found in table

Measurement instruments

The Portage Development Scale was used to evaluate the performances/acquisitions of the study participants. This evaluation tool allows to identify the level of development of children aged 0-6 years, both at the general level and on the 5 areas of development (motor, language, cognitive, personal autonomy, social). With the help of the inventory of behaviors and abilities, we obtained a rigorous assessment of the performances of the children, quantified in the development level on each of the 5 areas of the profile, as well as a general development level. Items are structured on age levels, describing specific behaviors that naturally occur in the harmonious development of a child for a certain age stage.

The results regarding the reliability of internal consistency of the scale indicated the following: socialization .80, language .81, autonomy .73, cognitive .70, motor skills .75, and for the whole scale, the coefficient of internal consistency indicated a result of .80 (Arvio, Hautamaki, & Tilikka, 1993), The results obtained by evaluating with the Portage development scale were compared with the level of development offered by other research tools. Both methods have shown almost identical cross-sectional results in the case of individuals with cognitive impairment, which argues for the use of this tool as a reasonable evaluation method in clinical research (Arvio et al., 1993).

Procedure

Family-centered therapy was used in the intervention aimed at the first sample of participants (N1-N3). Within it, parents, especially the mother of the child, participated actively in the evaluation phase of the child, where she generated a series of essential information about the child, used subsequently as starting points in the intervention, and during the implementation period of the program and/or its revision at regular intervals of 6 months. Thus, the family members provided information about the child (interests, strengths, abilities, difficulties, ways to convey to others the needs), so that later, together with the team of specialists, they set the objectives of the intervention program, the techniques used, the resources and the necessary means. Also, the activities initiated and/ or learned by the child together with the specialists were continued by the parents at home so that the behaviors acquired by the child are generalized in the most varied contexts. Also, in situations where parents encountered difficulties or identified new ways to obtain favorable results, they were discussed with the specialist and included, respectively rejected, as elements of the therapeutic intervention. The family's role in the therapeutic program was one of the partners, having the possibility to make decisions regarding the intervention and control during the program. Expert-centered therapy was used in the second sample of participants (N4-N6). Within them, the family was not involved in the evaluation, the setting of the objectives, the means and the resources used in the therapeutic program addressed to the 3 participants. In their case, the parents either did not show interest in getting involved in the child's therapy or were absent from his / her life (institutionalized child). In these conditions, the activities carried out with children were learned and strengthened together with the specialists, and the family and caregivers were advised to continue the activities at home.

Research design

The present study was based on the ABA experimental design on a single subject, conducted through 6 longitudinal case studies over a 4-year period (Table

-The first phase consists of evaluating the 6 participants in the study using the Portage Development Scale on all five areas (language, cognitive, social, personal autonomy and motor), in order to collect information and data to establish the basic level.

-The second phase of the study, consisting of conducting the experiment. Within this stage of the study, two intervention practices were used, respectively for sample 1 (Ef), which included N1-N3 participants, the intervention focused on family-centered therapy, and in the case of sample of participants 2 (Ee), included N4-N4 participants, the intervention focused on expert-centered therapy.

-The third phase of the study consists of the final evaluation aimed at determining both the differences existing between five development areas from the initial and final stage of the experiment, as well as the efficiency of the two therapeutic approaches analyzed from the perspective of the results obtained by the study participants, in the 4 years of intervention.

Findings

Conclusion

Final conclusions

Through this study, conducted over a period of 4 years, we decided to investigate the effectiveness of two models of approach to therapy, respectively specialist-centered therapy vs. family-centered therapy, in the case of children with nonverbal ASD, in terms of their development on the five areas of development (social, cognitive, language, personal autonomy, motor).

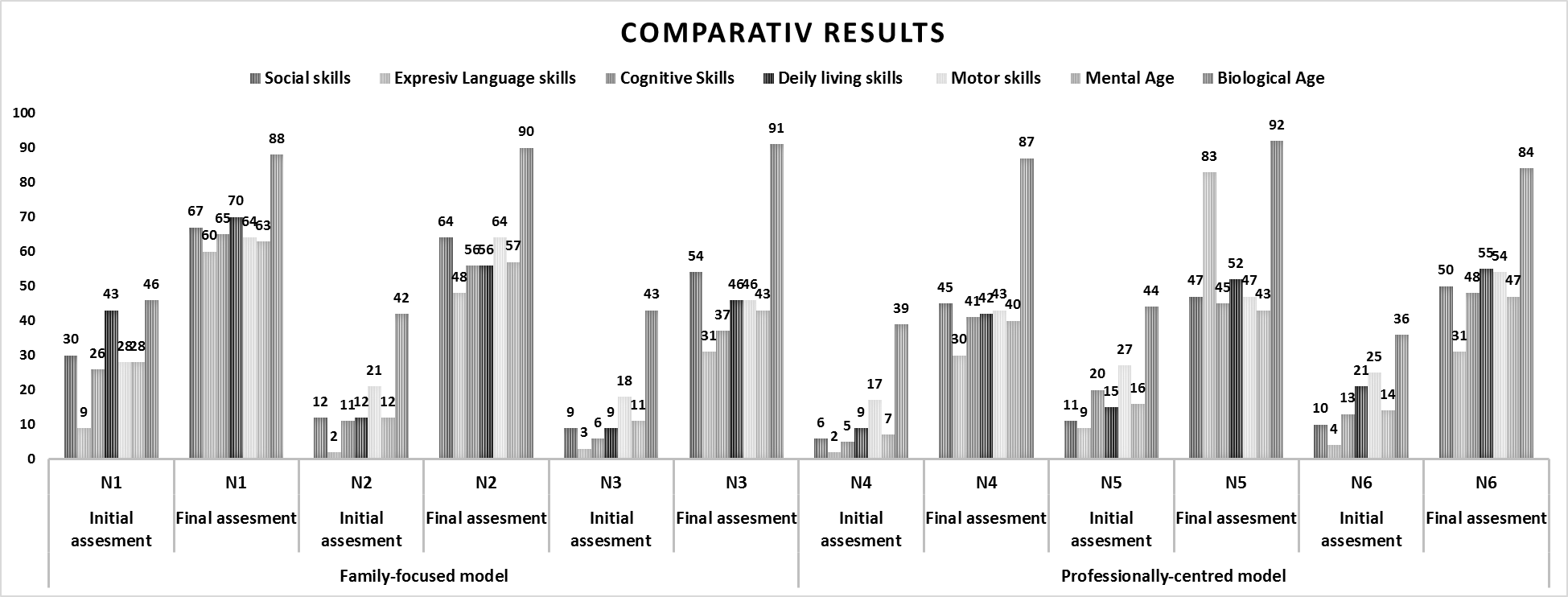

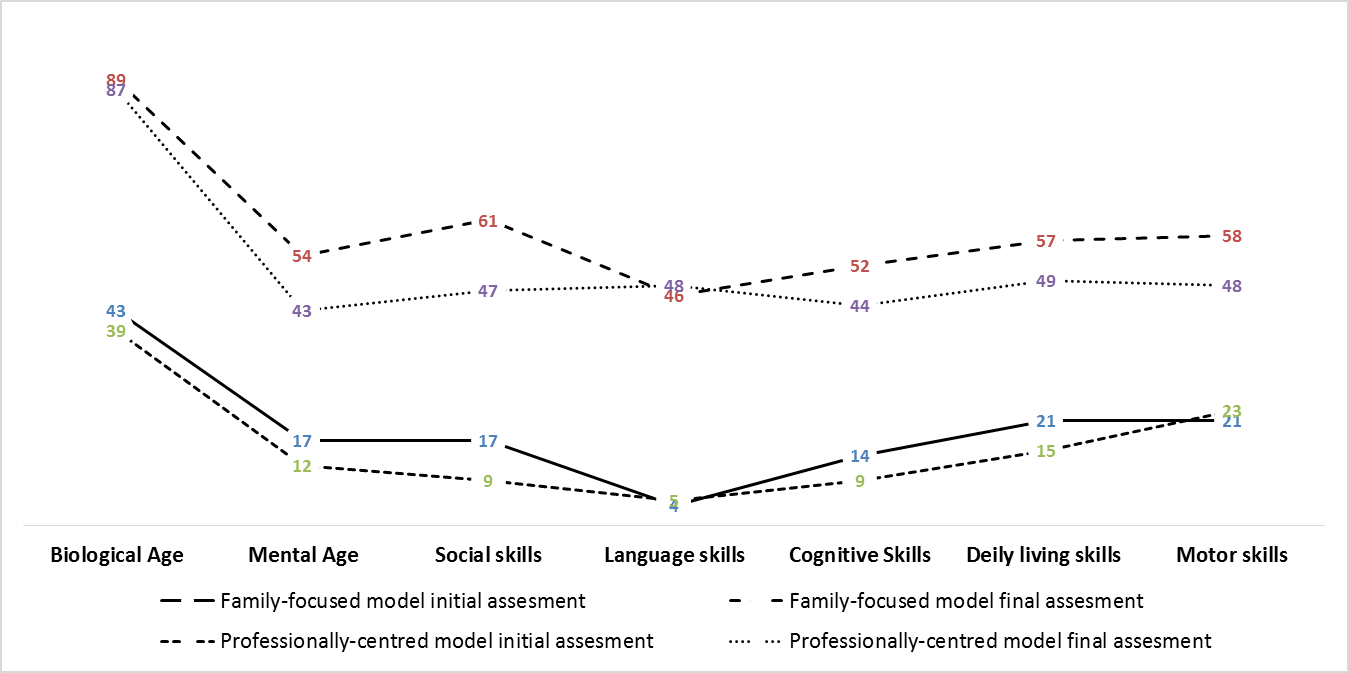

The results obtained in the research are in agreement with the results obtained in the specialized literature, respectively, the children with low-functional autism have significant deficits in all areas of development. Regardless of the type of approach (specialist-centered therapy or family-centered therapy), the data indicate a contoured developmental profile that is different from case to case (Fig. 3). What is similar for all 6 children investigated is the fact that communication deficits are the most severe, despite the acquisition of functional communication skills through AAFCs.

It was also found that the acquisition of functional communication skills stimulated the development of social skills, children interacting, within limits significantly below the average, with other people.

According to the data obtained and presented in table

The comparative analysis of the data on the two samples surprised that the average results for the 3 participants in the sample who benefited from family-centered therapy are better in terms of evolution as follows (Figure

Another significant difference in favor of family-centered therapy is the evolution of mental age. If in the case of children who have benefited from specialist-centered therapy the gap is 44 months, in the case of children who have benefited from family-centered therapy the gap is 9 months less than 44, 35 months respectively.

Less significant differences are also observed in the case of cognitive development and motor acquisition. Thus, the children who benefited from family-centered therapy recorded a gap between the biological age and the acquisitions in the sphere of cognitive abilities of 37 months, with 6 months less than in the case of the children who benefited from specialist-centered therapy, the difference being in this case of 43 months. Also, motor skills are more developed for children who have benefited from family-centered therapy, 8 months difference (the existing gap is 31 months), compared to children who have benefited from specialist-focused therapy (the gap being 39 months).

If the gap between the biological age and the mental age, social skills, cognitive abilities and motor skills are smaller in the case of children who have benefited from family-centered therapy, the data obtained have surprised smaller, but not significant differences in the areas of language and personal autonomy, in the case of children who have benefited from specialist-focused therapy. It was found that in the case of children who have benefited from specialist-centered therapy, the gap between the biological age and the level of language acquisition is 39 months, 3 months less than in the case of children who have benefited from family-centered therapy, where the gap is 41 months.

Significant differences between the two experimental samples can be found in the case of the specific acquisitions of the personal autonomy skills, where the children who have benefited from specialist-centered therapy have a gap of 38 months, 2 months less than the children who have benefited from focused therapy on the family, where the gap is 40 months.

By analyzing the data obtained as a whole, we can say that family-centered therapy for children with nonverbal ASD is more effective than specialist-centered therapy, the significant differences being noticeable in the following areas of development: social skills, cognitive abilities, motor skills and level of mental development, and insignificant, in favor of therapy focused on specialists, in the sphere of language and personal autonomy (Figure

The limits of the research and new directions of action

Beyond the results obtained and their value, this research has a number of inherent limitations. So, opting for case studies as a research method, entails a first limitation of this investigation. Therefore, the results obtained have no statistical value and cannot be generalized. In this respect, it is recommended to extend the present research, by selecting a statistically significant sample. Also, comparing the results obtained with those of a control sample, would provide a much more valuable connotation to the study, but we consider this approach to be unethical, respectively depriving some children with autism the chance to benefit from any intervention, just to be able to complete a control lot.

Another inherent limitation of this research is the ripening effect. During the course of the experiment, the participants were involved in their own evolutionary process, normal and natural. In these conditions there is the possibility that the differences that have arisen between the repeated measurements are due to some extent to their maturation and not just the manipulation of the experimental variable. In order to obtain the most valid data in this regard, it is recommended to carry out studies on comparative samples (experimental lot - control lot), but as mentioned above, this is unethical.

References

- Affleck, G., Tennent, H., Rowe, J., Roscher, B., Walker, L., & Higgins, P. (1989) Effects of formal support on mother’s adaptation to the hospital-to-home transition of high risk infants: the benefits and costs of helping. Child Development, 60, 488–501.

- Arvio, M., Hautamaki, J., & Tilikka, P. (1993). Reliability and validity of the Portage assessment scale for clinical studies of mentally handicapped populations. Child Care Health Dev. Mar-Apr, 19(2), 89-98.

- Bailey, D. B., Aytch, L. S., Odom, S. L., Symons, F., & Wolery, M. (1999), Early intervention as we know it. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 5, 11–20.

- Beukelman, D., & Mirenda, P. (2005). Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting Children and Adults with Complex Communication Needs (3rd edition). Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Co.

- Brewer, E.J., McPherson, M., Magrab, P.R., & Hutchin, V.L. (1989). Family-centered, community-based, coordinated care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics, 83(6), 1055-1060.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1975). Is early intervention effective?. In M. Guttentag and E. Struening (Eds.), Handbook of Evaluation Research (Vol. 2) (pp. 519–603). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Bruder, M. B. (2000) Family-centered early intervention: clarifying our values for the new millennium. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 20(2), 105–115.

- Campbell, P. H., & Halbert, J. (2002) Between research and practice: provider perspectives on early intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 22(4), 213–226.

- Crais, E. R., Roy V. P., & Free, K. (2006), Parents’ and professionals’perceptions of the implementation of family-centered practices in child assessments. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 365–377.

- Crais, E., & Calculator, S. (1998). Role of caregivers in the assessment process. In A. M. Wetherby, S. F. Warren, Reichle (Eds.), Communication and language interventions series: vol.7. Transitions in prelinguistic communication (pp. 261-283). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Piblishing Co.

- Dempsey, I., & Dunst, C. J. (2004). Help-giving styles as a function of parent empowerment in families with a young child with a disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 29, 50–61.

- Dempsey, I., & Keen, D., (2008). A Review of Processes and Outcomes in Family-Centered Services for Children With a Disability, Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 28, 42.

- Dunst C.J., Trivette C.M., Hamby D.W. (2006) Family support program quality and parent, family and child benefits. Asheville, NC: Winterberry Press.

- Dunst, C. J. (1999). Placing parent education in conceptual and empirical context. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 19, 141–147.

- Dunst, C. J. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. Journal of Special Education, 36, 139–147.

- Dunst, C. J., & Trivette, C. M. (2005). Measuring and evaluating family support program quality. Asheville, NC: Winterberry Press.

- Dunst, C. J., Boyd, K., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. W. (2002). Family-oriented program models and professional helpgiving practices. Family Relations, 51, 221–229.

- Dunst, C. J., Johanson, C., Trivette C. M., & Hamby, D. (1991) Family-oriented early intervention policies and practices: family-centered or not? Exceptional Children, 58, 115–126.

- Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Deal, A. G. (1988). Enabling and empowering families: Principles and guidelines for practice. Cambridge, MA: Brookline

- Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. W. (2007). Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 370–378.

- Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & LaPointe, N. (1994). Meaning and key characteristics of empowerment. In C. J. Dunst, C. M. Trivette, & A. G. Deal (Eds.), Supporting and strengthening families: Principles and guidelines for practice (pp. 12–28). Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books.

- Espe-Scherwindt, M., (2008); Family-centred practice: collaboration, competency and evidence. Support for Learning, 23(3), 136-143.

- Gallagher, P., Malone, D. M., Cleghorne, M., & Helms, K. A. (1997). Perceived inservice training needs for early intervention personnel. Exceptional Children, 64, 19–26.

- Heller, T., Miller, A. B., & Hsieh, K. (1999). Impact of a consumer directed family support program on adults with developmental disabilities and their family caregivers. Family Relations, 48, 419–427.

- Iacono, T., & Caithness, T., (2009). Assessment Issues. In P. Mirenda & T. Iacono (Eds.), Autism Spectrum Disorders and AAC (pp. 23-48). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Judge, S. L. (1997). Parental perceptions of help-giving practices and control appraisals in early intervention programs. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 17, 457–476.

- Keen, D. (2007). Parents, Families and Partnerships: Issues and considerations. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 54, 330–349.

- Keen, D., Rodger, S., Couzens, D., & Muspratt, S. (2010). The effects of an early intervention program for children with an autism spectrum disorder on parenting stress and competence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 229-241.

- King, G., Kertoy, M., King, S., Law, M., Rosenbaum, P., Hurley, P. (2003). A measure of parents’ and service providers’ beliefs about participation in family-centered services. Children’s Health Care, 32, 191–214.

- King, G., King, S., Rosenbaum, P., & Goffin, R. (1999). Family-centered caregiving and well-being of parents of children with disabilities: Linking process with outcome. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 41–53.

- Law, M., Hanna, S., King, G., Hurley, P., King, S., Kertoy, M. (2003). Factors affecting family-centred service delivery for children with disabilities. Child: Care, Health and Development, 29, 357–366.

- Mahoney, G., & Bella, J. M. (1998). An examination of the effects of family-centered early intervention on child and family outcomes. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18, 83–94.

- Martin, D., Garske J. P., & Davis, K. (2000), Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 438–450.

- McWilliam, R. A. (1999), Controversial practices: the need for a reacculturation of early intervention fields. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 19(3), 177–188.

- Mikus, K. C., Benn R., & Weatherston, D. (1994), On Behalf of Families: a sourcebook of training activities for early intervention. Detroit, MI: Project FIT, Merrill-Palmer Institute, Wayne State University.

- Murray, M. M., & Mandell, C. J. (2006). On-the-job practices of early childhood special education providers trained in family-centered practices. Journal of Early Intervention, 28, 125–138.

- O’Neil, E., Palisano, R. J., & Westcott, S. L. (2001). Relationship of therapists’ attitudes, children’s motor ability, and parenting stress to mothers’ perceptions of therapists’ behaviours during early intervention. Physical Therapy, 81, 1412–1424.

- Reich, S., Bickman, L., & Heflinger, C. A. (2004). Covariates of selfefficacy: Caregiver characteristics related to mental health services self-efficacy. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 12, 99–109.

- Shelton, T. L., Jeppson, E. S., & Johnson, B. H. (1987). Family-centered care for children with special health care needs. Bethesda, MD: Association for the Care of Children’s Health.

- Spe-Scherwindt, M., (2008). Family-centred practice: collaboration, competency and evidence. Support for Learning, 23(3), 136-143.

- Stormshak, E. A., Dishion, T. J., Light, J., & Yasui, M. (2005). Implementing family-centered interventions within the public middle school: Linking service delivery to change in student problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 723–733.

- Trivette, C. M., Dunst, C. J., & Hamby, D. W. (1996). Factors associated with perceived control appraisals in a family-centered early intervention program. Journal of Early Intervention, 20, 165–178.

- Trivette, C. M., Dunst, C. J., Boyd, K., & Hamby, D. W. (1995). Family-oriented program models, helpgiving practices, and parental control appraisals. Exceptional Children, 62, 237–249.

- Trivette, C. M., Dunst, C. J., Hamby, D. W., & LaPointe, N. J. (1996). Key elements of empowerment and their implications for early intervention. Infant -Toddler Intervention, 6, 59–73.

- Trute, B., & Hiebert-Murphy, D. (2007). The implications of ‘‘working alliance’’ for the measurement and evaluation of family-centered practice in childhood disability services. Infants Young Child, 20, 109–119.

- van Schie, P. E. M., Siebes, R. C., Ketelaar, M., & Vermeer, A. (2004). The measure of process of care (MPOC): Validation of the Dutch translation. Child: Care, Health and Development, 30, 529–539.

- Wade, C. M., Mildon R. L., & Matthews, J. M. (2007), Service delivery to parents with an intellectual disability: family-centred or professionally-centred? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 87–98.

- Wilson, L. L. (2005), Characteristics and consequences of capacitybuilding parenting supports. CASEmakers, 1(4), 1–3.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

17 June 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-084-6

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

85

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-814

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Crișan, C. (2020). The Role Of Family In Therapy Of Children With Asd. In V. Chis (Ed.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2019, vol 85. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 163-175). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.06.17