Abstract

News and mass communications have long been integral components of world affairs. Their growing weight, which can be accounted for by the blistering rise in information and communications technologies (ICT), has caused some radical changes around the globe. As a result, knowledge and news, as well as ICT, are being integrated in every aspect of our daily lives at both private and public levels. They are being treated as commodities and viewed as a strategic resource. It is for this reason that building one’s national news and communications infrastructure should be recognized as an essential strategic objective for every nation. Yet, at the same time, the current phase of the information revolution has brought about a number of serious challenges from political, economic, and even civilizational perspectives. Our dependency on information technologies poses a danger of someone using the latter for malicious purposes. Thus, one has to be mindful of the fact that ICT, when skillfully manipulated, can help dismantle the existing orders, i.e. overthrow political regimes that once enjoyed relative stability and control. That is why it seems a matter of high relevance for countries not only to create benign conditions for the development of the ICT-sector but also to devise mechanisms of protection in the area of news and communications. Drawing on our study of the global information and communications flows, we intend to identify some key manipulative practices – strategies and tactics – that are being employed as instruments of psychological warfare to advance “color revolutions.”

Keywords: Information and communication technologiespsychological securitypsychological warfaremanipulative practicessocial mediapropaganda

Introduction

News and mass communications have long been integral components of world affairs. Their growing weight, which can be accounted for by the blistering rise in information and communications technologies (ICT), has caused some radical changes around the globe. As a result, knowledge and news, as well as ICT, are being integrated in every aspect of our daily lives at both private and public levels. They are being treated as commodities and viewed as a strategic resource. It is for this reason that building one’s national news and communications infrastructure should be recognized as an essential strategic objective for every nation. Yet, at the same time, the current phase of the information revolution has brought about a number of serious challenges from political, economic, and even civilizational perspectives. In fact, our dependency on digital systems implies that we increasingly must question whether we can trust those and how it is possible to know that our computer is behaving as we expect it to or that an e-mail from our colleague is indeed from that colleague? ( Singer & Friedman, 2014, p. 46) And one has to be mindful of the fact that ICT, when skilfully manipulated, can help dismantle the existing orders, i.e. overthrow political regimes that once enjoyed relative stability and control.

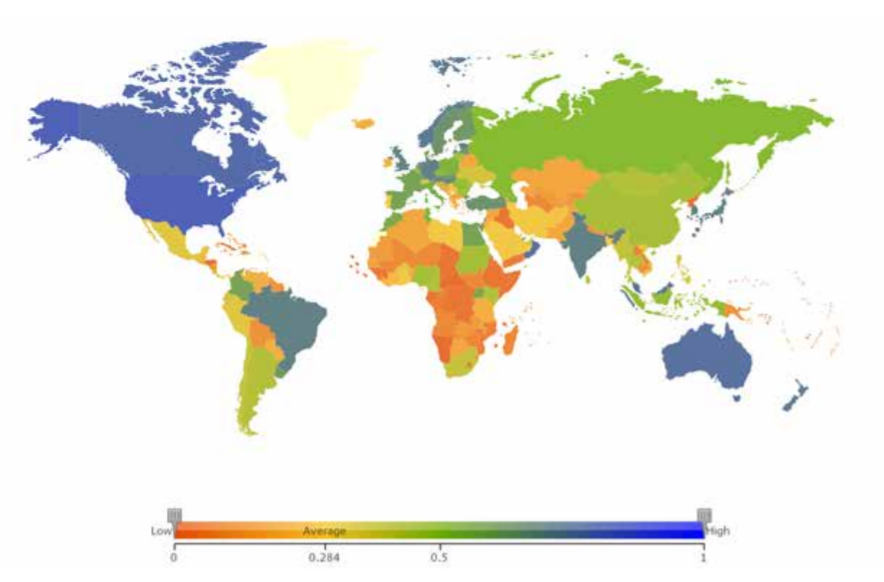

It is quite telling that in their annual report published in 2015 the International Telecommunication Union introduced a new indicator for the ICT-readiness that measured the level of cybersecurity by region.

As one can see from the figure

Yet, even the developed nations, despite their thoroughly crafted national policies that supposedly provide for a high level of cybersecurity, are still susceptible to a variety of cyberattacks. This point is just more evidence that today “effective cybersecurity is more of a dream than a reality” ( Rosenzweig, 2012, p. 25).

Therefore, it seems a matter of high relevance for countries not only to create benign conditions for the development of the ICT-sector but also to devise mechanisms of protection in the area of news and communications.

Problem Statement

The fact that the U.S. is dominant in most areas including news and communications raises the issue of a serious misbalance and uneven capabilities to disseminate information in today’s world. With ICT being concentrated in the hands of a few, there exists an asymmetry of distribution wherein information is exported mainly by several developed nations to the rest of the world.

One can try to account for the reasons of this asymmetry by making the argument that the Internet, as well as ICT, was invented in the West, primarily in the USA. Moreover, most global media corporations are headquartered in the USA, Canada, the UK, France, Germany and a few other Western nations. Those media manage a great number of correspondents all over the world, broadcast to dozens of countries, and can serve as effective instruments to channel Western values and promote the Western way of life to the people with entirely different cultural and civilizational backgrounds.

Thus, one can argue that people around the globe see the world almost exclusively through the eyes of Western media and their journalists. This allows Western governments to take advantage of their dominance in the area of news and communications to conduct policies aimed at achieving a global geopolitical leadership in particular by manipulating public opinion in various countries to topple any unwanted regime. The rise of the Internet and ICT has simplified this process while the information asymmetry continues to grow. In fact, there exists a paradox: on the one hand ICT should facilitate access to information for people in various distant corners of the globe, yet, on the other hand only the developed nations truly benefit from such technologies, particularly when the latter are used as a powerful instrument to manipulate public opinion on a planetary scale. In fact, those nations constitute the symbolic elites who exercise manipulation as a “discursive form of elite power reproduction that is against the best interest of dominated groups” ( Dijk, 2006, p. 364) and reproduces information inequality.

So, it would not be an overstatement to argue that the Internet and ICT can present a real danger to national security of quite a few countries. Specifically constructed news disseminated through Twitter and Facebook makes it possible to engage large audiences. In and of themselves, as is evident, social media can be an effective instrument of manipulating public opinion to achieve the following three main ends: engagement, communication, and mobilization. To merely inform the public is often not the sole objective of social media. What does in fact emerge behind the scenes are “inevitably automated systems that engineer and manipulate connections,” so as “to be able to recognize what people want and like,” while “Facebook and other platforms track desires by coding relationships between people, things, and ideas into algorithms” ( Dijck, 2013, p. 12).

Furthermore, one should bear in mind that the headquarters of Twitter and Facebook are located in the United States, and while these companies operate in accordance with U.S. regulations, they do not have to abide by the legal code of other countries where their activities are conducted, failing to filter the content posted on their platforms. Besides, it has to be pointed out that those platforms “provide space for non-journalists to reach a mass audience,” while the emergent “citizen journalism challenged the link between news and journalists, as non-journalists began to engage in journalistic activities to produce journalistic outputs, including news” ( Tandoc, Lim, & Ling, 2018, p. 138). And so the normative principles that are part of the professional codes of ethics of journalism and “what counts as 'legitimate' forms of interaction and communication” ( Dijk, 2006, p. 364) may no longer apply.

Moreover, there is ample opportunity now for the operatives of Western intelligence agencies to take advantage of social media platforms in order to excite dissatisfaction and provoke mass protests. Thanks to anonymity, it is absolutely impossible for ordinary social media users to identify the actual person behind a Facebook or Twitter account. So, posts and tweets become an effective weapon in psychological warfare. Take for example the protests in North Africa that erupted in January 2011 and became known as the Arab Spring or alternatively as ‘Twitter revolutions'. The latter dubbing bears witness to the manipulative role that social media had played in escalating the uprisings. Twitter and Facebook, which enjoy enormous popularity in Africa, served as a platform to instigate mass protests. This point is corroborated by what Wael Ghonim, a Google marketing executive, once said. In his interview to CNN, speaking on the civil unrest in Egypt, he pointed out that this “revolution started online,” that it “started on Facebook,” and that it broke out “when hundreds of thousands of Egyptians started collaborating content” when “a video posted on Facebook would be shared by 50,000 people within a few hours,” adding that “if you want to liberate a society just give them the Internet” ( Doran, 2011, p. 39).

Political leaders across North Africa were cognizant of the threat that social media had posed. For instance, in March 2011, the Egyptian authorities switched off people's access to the Internet for a period of three days, yet they were still unable to rein in the situation. As the events in North Africa clearly demonstrated, social media can serve as an extremely effective tool for an expedient mobilization of great numbers of people even where there seemed to be some relative stability of political regimes. Yet, governments proved unable to withstand their mobilizing power.

In fact, in can be further argued that the governments in North Africa suffered a total defeat in the course of psychological warfare. Those political leaders could have succeeded had they enjoyed a strong support of their citizenry and had the latter been indifferent to the calls for protest that were delivered through Facebook and Twitter. Clearly, those governments had underestimated the effect and power of social media.

Despite the higher levels of social and economic development as compared to most other African nations, there were great numbers of disillusioned people in North Africa, and their frustration had been stirred up by social media. Therefore, it is advisable to counter the challenge by putting in place an effective mechanism of control over social media and other digital content.

However, social media and the Internet were not the only instruments of psychological warfare. The other source of trouble, as widely recognized, was Western news channels. Despite their nominal support for plurality of opinion or the so-proclaimed freedom of speech, they share a certain tendency of treating any political development strictly from those angles that are highly recommended by Foreign Offices of their respective governments.

The psychological war against Libya presented a salient example of an active role that Western media had played in overthrowing the regime that used to be quite stable and popular with the people. One should recall that only in November 2010, Muammar Gaddafi was hosting the delegates of the EU-Africa summit held in Tripoli. Yet, two months later, thanks to the Western media efforts, his positive image was ruined totally and across the whole continent of Africa.

Some Western governments were pushing for the adoption of the Security Council resolution that granted them the right to aid the opposition in Libya. But in order to get there, they had to frame Muammar Gaddafi as a 'bloodthirsty tyrant' who had brutally clamped down on peaceful protests. The Libyan opposition, on the contrary, was being represented as the only force capable of negotiation. This was a common overarching narrative exploited by all Western media across the board. At the same time, they had to convince their own publics that the only way to solve the Libyan crisis was to launch a military operation against the Gaddafi regime. According to that logic, the only solution to quickly resolve the conflict and to put an end to the civil war was for NATO to bomb the Libyan territory. The casualties among the civilians as a result of the air strikes were either silenced or blamed on the Gaddafi regime. Here manipulation of social cognition evidenced itself as dominant groups made sure that “relevant and potentially critical general knowledge [was] not acquired, or that only partial, misguided or biased knowledge [was] allowed” ( Dijk, 2006, p. 371).

Moreover, the messaging of Western media was supposed to affect the pro-government forces as regards the real potential of the opposition in order to sow the seeds of panic among Gaddafi’s supporters.

It is hard to say whether or not the entire set of objectives of the psychological war against the Libyan government had been achieved, but what remains clear is that the negative image of Muammar Gaddafi had been successfully constructed and he found himself completely isolated in the face of Western military aggression without the support either inside or outside the country.

As the Libyan case saliently demonstrated, almost any regime can fall victim to psychological engineering. Thus it is of an immediate interest to research into the practices of neutralizing the negative impact from massive bombardment by visually convincing messages disseminated both through social media and by traditional news channels employed by Western spin doctors.

Research Questions

-

Based on the above problem statement the authors posed the following research questions:

-

How does one avoid losing sight of the system of references in the global information and communications realm to be able to detect that manipulative practices are being used?

-

What are some key manipulative practices commonly used in spin doctoring?

-

How does one counteract those manipulative practices?

Purpose of the Study

Drawing on our extensive research of the global information and communications flows, the authors intend to identify some key manipulative practices – strategies and tactics – that have been employed as instruments of psychological warfare in engineering “color revolutions.”

Research Methods

The methodology of our research draws primarily on the principals of critical discourse analysis (CDA) that endeavors to identify and explicate the relationships between dominance and discourse. Power and dominance are based on the privileged access to discourse and communication ( Dijk, 1993). In our case it is a few Western nations that control exclusively what is said and shown and how it is said and shown on their international news channels and what is consequently funneled through their social media and narrated yet again in strict alignment with their orders of discourse. And the same is true for their control of public opinion, “and hence for the manufacture of legitimation, consent and consensus needed in the reproduction of hegemony” (Margolis & Mauser, 1989 as cited in Dijk, 1993, p. 257). Special attention is drawn to the notion of manipulation which is treated as a form of interaction, i.e. as a 'communicative' or 'symbolic' form of manipulation, such as the media manipulating viewers or readers “through some kind of discursive influence” ( Dijk, 2006, p. 360). “Manipulation not only involves power, but specifically abuse of power, that is, domination” and therefore implies the exercise of “illegitimate influence by means of discourse” (ibid, p. 360). When the recipients are unable to recognize the real intentions of the manipulator or to foresee the end result of the actions and beliefs imposed on them, negative consequences of manipulative discourse are incurred.

We also turn our attention to cognitive dimension of manipulation that “involves strategic understanding processes that affect processing in STM [short-term memory], the formation of preferred mental models in episodic memory, and … the formation or change of social representations, such as knowledge, attitude, ideologies, norms and values” (ibid, p. 372).

Findings

The present analysis helped identify the most common manipulative practices that have been used by both Western news channels and social media in order to engineer public opinion:

Discursive group polarization. This manipulative practice implies emphasizing fundamental values such as democracy and freedom attached to 'Us' and who 'We' support and contrast those with the 'evil' ones attributed to 'Others'. In this vein Western media manufactured the construct of 'freedom fighters' and 'moderate opposition' out of the armed Islamic rebels who fought the Assad government and who were 'illegally' attacked by the latter with chemical weapons. Thus, “a very emotional event with a strong impact on people's mental model [was] being used in order to influence these mental models as desired” ( Dijk, 2006, p. 370). By constant repetition and exploitation of other such incidents (the use of chemical weapons) a preferred model may be generalized to construct a stable social representation of the 'evil Other.' What is important here is that “the real interests and benefits of those in control of the manipulation process are hidden, obscured or denied, whereas the alleged benefits for 'all of us', for the 'nation', etc. are emphasized” ( Dijk, 2006, p. 370). Once the recipients are affected, little or no further manipulation attempts may be required to make people accept the imposed views, and so the mind programming has been achieved.

Constructing premonitions. It implies an impending disaster such as economic collapse or a sense of frustration about the living standards in the country framed so negatively that, when reaching the tipping point, provoke mass protests, panic, frustration and disarray. It starts both by the news outlets and in social media and manifests itself in a surge of criticism by popular bloggers, political and public figures, representatives of the opposition and social movements who promote dissatisfaction with the authorities by highlighting a variety of negative themes. This overwhelming surge makes one believe that virtually everyone is critical of the government – that there exists a growing popular dissatisfaction that is about to spill over into a protest movement or a coup d’états. This brainwashing phase called 'preparation' is followed by 'virtual reality' or a phantasm of staged mass protests. Then, when people are convinced, the actual protests break out.

The use of biased or fake news and staged events is another manipulative practice. Because in our Western culture most people are emotionally moved by human suffering, loss of life, civilian casualties, and etc., it is exactly such tragic events that Western media draw upon most frequently for their propaganda. Yet, at the same time, such footage, wherein somebody is being victimized, does not have to be corroborated by solid evidence – just bare accusations normally suffice to point at a designated villain. Given that such accusations are brought forward by a 'reliable' source, for example by U.S. or U.K. intelligence and circulated by 'reliable' Western news outlets, for example CNN, BBC, or ARD, no further proof is required. And so “fake news in the form of manipulated images and videos intended to create false narratives” ( Quintanilha, Silva, & Lapa, 2019, p. 19) emerge. For example, in 2013, footage showing victims of a chemical attack in Eastern Ghouta was aired on all major news channels. And it was mainly due to Russia’s efforts that they failed to convince the international community that it was the Assad forces who had used the chemical weapons.

However, in 2017, some similar footage resurfaced. This time it was about an alleged chemical attack taking place in the suburb of Idlib. As a result, the incident triggered a U.S. retaliatory strike against the Syrian air base located on the outskirts of Homs. No independent investigation regarding that incident was initiated even after the discovery of a secret underground laboratory which specialized in production of chemical weapons on the outskirts of Aleppo. Finally, in 2018, another provocation took place now in Duma, a suburb of Damask. Earlier in April 2018, the White Helmets, a humanitarian organization financed by Great Britain and the United States, was alleged to be involved in spreading fake stories. It produced a video with some 'proof' that chemical weapons had been used by the Assad government forces. This video was immediately recirculated by Western news outlets. As a result, foregoing the official investigation of the incident in Duma, President Trump ordered a pre-emptive missile strike against Syria. The Russian side once again presented evidence that the events in the video had been staged. They even found the boy who was featured in the video and who confessed on camera that it was the White Helmets who had hired and payed the civilians for taking part in the production of that footage. However, Western news channels chose to ignore the revelation and pronounced Assad guilty of the war crimes anyway. In fact, these cases in Syria are just another testimony to the ongoing trend to mediatize political conflicts that take place in the international arena ( Pantserev, Melnik, & Sveshnikova, 2018).

Taking stock of the Syrian cases, one can draw a conclusion that Western spin doctors are working hard to deconstruct the reputation of Russia as a responsible actor in the international arena. Most certainly their propaganda is not limited to Russia's military operation in Syria, but the latter presents an easy target for their criticism. This is why, every now and then, Western news outlets produce reports accusing Russia of striking hospitals, schools and other civilian infrastructure or of conducting cyberattacks, violating human rights, and etc. For example, in September 2016, the New York Times published an article titled “Russia’s Brutal Bombing of Aleppo May be Calculated, and it May be Working”, displaying a photo of a blown down building accompanied with a lead that read ‘Russia’s bombing campaign in the Syrian city of Aleppo has destroyed hospitals and schools, choked off basic supplies, and killed aid workers and hundreds of civilians over just days’ ( Fisher, 2016, p. 1). A series of similar reports followed under such titles as “U.S. Condemns Russia for Cyberattack, Showing Split in Stance on Putin’, ‘Cyberattacks Put Russian Fingers on the Switch at Power Plants, U.S. Says”’, and the like. Surely, the New York Times is not alone to jump the bandwagon. Not far behind is the Washington Post with a story titled “Russia’s Frantic Parade of Lies” ( The Washington Post, 2018) among the authors of which there is a whole roster of contributors most of whom serve on the newspaper's board of editors, suggesting that it is a reflection of its editorial policy to smear Russia's image. And the list can go on.

Russia is certainly trying to use a range of instruments to get across its official point of view on the events around the world. For example, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov often turns to such Western news media giants as CNN and BBC to name a few. Yet, his position is frequently distorted or re-contextualized in the Western media before it can reach their audiences. When interviewing Russian officials, Western journalists often a priori take an accusative angle toward Russia. To cite an example, consider the interview Putin gave to the Austrian TV channel ORF which aired in June 2018. In it the interviewer interrupted the Russian President at least ten times, throwing questions without hearing out the answers. This is an example of a high concept form of talk that typifies the genre of current Western journalism – an industrial expressivity motivated by commercial and/or ideological orientation of their style which leaves the interviewee no freedom of expression ( Golubev, 2017).

With a view to improve its image abroad as well as to communicate to international audiences directly Russia launched its own news organizations, namely Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik. Both cover major developments around the globe in a manner contradictory to the Western orders of discourse, which often gets them in trouble with communications services regulators in the United States and the United Kingdom. Thus, RT had to register as an agent of a foreign government in the U.S. and it regularly gets fined by Ofcom for ‘breaches in impartiality’ ( The Telegraph, 2019) in the U.K. On the whole, the Russian media abroad find themselves in rather complicated circumstances, not only having to endure a most competitive international news market environment but also to survive in psychological warfare against some powerful Western media companies who are still well in charge of managing world public opinion.

Conclusion

In conclusion, one should provide an answer to the question of how it is possible to deal with the rising challenges discussed above. One seemingly logical response would be to counter fake news with hard facts. But it is only one side of the equation for it is impossible to win a “fake news” battle only at the level of content ( Albright, 2017, p. 87). Thus “indisputable facts play only a partial role in shaping the framing of words and images that flow into an audience’s consciousness” ( Entman, 2007, p. 166). That is because in most cases people believe what they want to and they do not want to invest time to verify the information they receive by turning to different sources. Therefore, to counter fake news one should use a combination of actions.

First, it is of the utmost importance to communicate to audiences, both foreign and domestic, to inform the public about the official policies in order to win the support of one’s citizenry. Furthermore, it is the key media channels that should help the government in forming a positive image in the eyes of both foreign and domestic audiences.

At the same time, it is advisable that embassies and consulates use every opportunity to engage international media more actively in order to get across the official position of the country by holding press conferences and briefings for foreign journalists. The use of this practice makes a lot of sense since it can help international audiences gain an alternative perspective on the developments around the world diverging from the ones commonly held by Western media. At the same time, it would be wise to react to ungrounded speculations that Western media often circulate by filing lawsuits against them. Such measures could reduce the level of intensity of psychological warfare.

Secondly, it is imperative to strengthen national news and communications potential by engaging talented journalists and opinion leaders to communicate public policy with impartiality to the citizenry shedding light on the falsehoods produced by Western spin doctors who aim at weakening public trust and creating fractures between the people and the government.

Last but not least, success in psychological warfare could be achieved if scores of regular online users express their views and their confidence in governmental policy. The challenge is to encourage those people who support the authorities to be more active in voicing their positions whereas they usually take a rather passive stance. Because they often come from different backgrounds and tend to belong to various social strata it is often hard to find common ground to consolidate their support. So, what is needed it to try to bring those people around some common project or a shared value system that can be called the ‘National Idea’.

The National Idea can be incorporated into the Concept of the Ideational Policy, comprising the cultural tradition, the system of values, and collective memories that lie at the heart of collective identity of every nation. The interests of ethnic minorities should be integrated into the Concept as well. Finally, mutual trust between the government and the widest possible majority of citizens should be established. At the same time, the government should invest into improving media environment of the country. In other words, people should be educated to discern the practices of manipulation within information flows so as not to succumb to the propaganda of mind engineering that makes use of the possibilities inherent in information and communications technologies.

One should bear in mind that only broad popular support for public policy can guarantee the survival of a nation in today’s world, particularly when pursuing an independent, self-reliant foreign policy based on one’s national interests and guided by one’s cultural values. If such support is lacking, the information flows coming from abroad can easily result in fatal consequences. There is a plethora of historic examples when psychologic warfare unleashed by Western media brought countries to civil war and national collapse. Learning how to counter such challenges is the only way to reduce the pressure from information flows that come from powerful Western media to guarantee the survival of a nation in times of psychological warfare.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge St Petersburg State University for the research grant 26520757.

References

- Albright, J. (2017). Welcome to the Era of Fake News. Media and Communication, 5(2), 87-89. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v5i2.977

- Dijck, van J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford and New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Dijk, van T. A. (1993). Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 249-283.

- Dijk, van T. A. (2006). Discourse and manipulation. Discourse & Society, 17(3), 359-383.

- Doran, M. S. (2011). The Impact of New Media: the Revolution will be Tweeted. In Kenneth M. Pollack, et al., The Arab awakening: America and the transformation of the Middle East (pp. 39-46). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Entman, R. M. (2007). Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 163– 173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x

- Fisher, M. (2016). Russia’s Brutal Bombing of Aleppo May be Calculated, and it May be Working, The New York Times, September 29. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/29/world/middleeast/russias-brutal-bombing-of-aleppo-may-be-calculated-and-it-may-be-working.html

- Golubev, K. A. (2017). The Criteria for Low Concept Form of Talk in TV News Content Production: A Case of the Interview Genre. Modern Science Journal, 8(3), 7-13.

- Measuring the Information Society Report. (2015). “Measuring the Information Security Report.” Accessed October 21, 2019. http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis2015.aspx

- Pantserev, K., Melnik, G., & Sveshnikova, N. (2018). Content analysis of media texts covering crises on practical seminars on political psychology as a necessary condition of the upgrade of the students’ communicative culture (on the example of chemical attack in Ghouta in 2013). Media Education, 3, 108-118.

- Quintanilha, L. T., Silva, M. T., & Lapa, T. (2019). Fake news and its impact on trust in the news. Using the Portuguese case to establish lines of differentiation. Communication & Society, 32(3), 17-33.

- Rosenzweig, P. (2012). Cyber Warfare: How Conflicts in Cyberspace are Challenging America and Changing the World. Santa Barbara: Praeger.

- Singer, P., & Friedman, A. (2014). Cybersecurity and Cyberwar: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tandoc, E. C., Lim, Z. W., & Ling, R. (2018). Defining “Fake News”. A Typology of Scholarly Definitions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 137-153.

- The Telegraph (2019). Russia Today fined £200,000 over ‘serious failures’ when covering Salisbury poisoning, by Katie O’Neill. July 26. Accessed October 31, 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/07/26/russia-today-fined-200000-serious-failures-covering-salisbury/

- The Washington Post (2018). Russia’s Frantic Parade of Lies, by editorial board. April 17. Accessed October 23, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/russias-frantic-parade-of-lies/2018/04/16/5895d86a-4199-11e8-ad8f-27a8c409298b_story.html

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

12 March 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-079-2

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

80

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-483

Subjects

Information technology, communication studies, artificial intelligence

Cite this article as:

Pantserev*, K. A., & Golubev, K. A. (2020). Manipulative Practices In Psychological Warfare: New Challenges In The New Age. In O. D. Shipunova, V. N. Volkova, A. Nordmann, & L. Moccozet (Eds.), Communicative Strategies of Information Society, vol 80. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 281-290). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.03.02.33