Abstract

According to recent studies, teachers’ well-being is a significant contributor to teacher effectiveness in terms of students’ academic achievement, so it would be worth finding out what contributes to teachers’ well-being. By extending previous research that revealed the positive relationship between the calling orientation and well-being and the negative between job/career orientation and well-being, the present study aimed to explore the role of flow in different life domains as mechanisms underlying this relationship, with an accent on flow at work. Correlational research design was used to examine the relationship between work orientations, flow in different life domains and flourishing of 315 classroom teachers from Croatia. The following self-report measures were used: Work-Life Questionnaire, Swedish Flow Proneness Questionnaire, and Flourishing Scale. Three parallel mediations were performed to test the hypothesized mediation role of flow in different life domains on the relationship between work orientations and flourishing. Results showed that career orientation was insignificant for teachers’ flourishing. Flow at work partially mediated the positive relationship between calling orientation and flourishing, and the negative relationship between job orientation and flourishing. The study provides empirical support for the role of flow at work relationship between calling and wellbeing, suggesting that flourishing of calling oriented teachers can be enhanced by experiencing flow at work.

Keywords: Flourishingflowteacherswork orientations

Introduction

The positive relationship between happiness and various success-related outcomes (e.g. job autonomy, job satisfaction, job performance, helping colleagues, popularity, and income) had already been supported through various cross-sectional studies, while longitudinal, and experimental research provides additional evidence that happiness precedes and leads to career success, rather than vice versa (for a review see Walsh, Boehm, & Lyubomirsky, 2018). In the context of the teaching profession, growing research interest in the last two decades has revealed that teachers’ well-being fosters students' motivation (e.g. Sutton & Wheatley, 2003), well-being (e.g. Bakker, 2005, Sisask et al., 2014), academic achievement (e.g. Briner & Dewberry, 2007; Duckworth, Quinn, & Seligman, 2009), and supportive classroom climate and teacher-student relationships (e.g. Ihtiyaroğlu, 2018; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). Teachers’ well-being contributes to their own effectiveness (for a review, see McCallum, Price, Graham, & Morrison, 2017), but what contributes to their well-being? Thus, the current research explores the role of teacher attitudes towards their work and flow experience in different activities in their well-being.

Work Orientations –a Calling, a Career or “Just” a Job

Research suggests that people tend to frame their relationship to work in three different ways that determine their experience of work and its accompanying thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (Wrzesniewski, 2003). Bellah and colleagues (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 1985) were the first who presented the tripartite model of work orientations based on distinct subjective meanings attached to work: job, career, and calling. Afterwards, Wrzesniewski, McCauley, Rozin, & Schwartz (1997) provided empirical support for this model using a diverse sample of employees. Job orientation implies seeing work as “just a job” - a source of financial stability/security. Hence, one’s identity, interests, and ambitions are not expressed through one’s work. Career orientation implies seeing work as a source of opportunities for advancement and achievement in terms of gaining promotion, higher social and financial status, power and prestige within the scope of one’s occupation, and is therefore partially related to one’s identity. And finally, calling orientation refers to seeing work as a fulfilling and purposeful, intrinsically rewarding, socially-useful and central part of one’s identity. Due to the variety of definitions, mostly in terms of meaningful passion, purpose and/or meaning in life, Duffy and his colleagues (Duffy, Dik, Douglass, England, & Velez, 2018), in their recent article, emphasized a need for conceptual clarity of this phenomenon. Trying to capture its crucial components, they defined calling as “an approach to work that reflects seeking a sense of overall purpose and meaning and is used to help others or contribute to the common good, motivated by an external or internal summons” (p. 426). Similarly, Steger (2017) defined it as “… work that is personally meaningful, is motivated by an interest in serving a prosocial benefit, and in addition is a response to a summons to work that comes from transcendent sources, such as religious Higher Powers, respected authorities, or perceived societal need.” (p. 65).

Bunderson and Thompson (2009) suggested that calling can be both binding and ennobling: on the one hand, as a source of identity, broader meaning and significance in one's work and occupation, and on the other hand, as a sources of obligation in terms of moral duty, sacrifice of pay, personal time, and comfort and vigilance towards higher standards. This neoclassical theoretical approach has been empirically confirmed in numerous studies. Hence, during the past few years, there has been a growing scholarly interest mainly regarding the calling orientation (e.g., Clinton, Conway, & Sturges, 2017; Duffy et al., 2018; Rawat & Nadavulakere, 2015).

Calling Orientation

Studies have repeatedly shown that an individual's sense of a calling has beneficial effects on one's professional and personal life. Calling orientation is related to several positive employee attitudes and performance such as positive job attitudes (Zhang, Hirschi, Herrmann, Wei, & Zhang, 2015), career outcome expectations, occupational choice, interests, and goals (e.g., Kaminsky & Behrend, 2015), greater self-reflection (Hirschi, 2012), work engagement, affective and normative occupational commitment, career satisfaction (e.g. Dobrow, 2006; Duffy, Allan, Autin, & Douglass, 2014; Hirschi, 2012; Sawhney, Britt, & Wilson, 2019; Xie, Xia, Xin, & Zhou, 2016), and higher levels of job performance (e.g. Lee, Chen, & Chang, 2016; Park, Sohn, & Ha, 2016). Hall and Chandler (2005) even claim that a sense of calling is the fundamental form of subjective professional success while it fosters the acquisition of meta-competencies (e.g., adaptability, engagement (Xie et al., 2016)) which eventually improve individual and organizational performance. As mentioned earlier, calling orientation is associated with work-related and life-related well-being. Individuals with callings are more satisfied with their jobs and life, and they put in more effort and time at work, regardless of whether or not it is compensated, than those with job or career orientations (Peterson, Park, Hall, & Seligman, 2009; Wrzesniewski et al., 1997). They tend to endorse higher levels of job satisfaction, work meaning, life meaning, zest, life satisfaction (e.g., Dobrow & Tosti-Kharas, 2011; Duffy & Dik, 2013; Duffy, England, Douglass, Autin, & Allan, 2017; Peterson et al., 2009), cope better with stress and have lower depression (e.g., Treadgold, 1999). Besides quantitative studies, several qualitative studies have also confirmed that individuals with a sense of calling often report high levels of fulfilment and happiness (Duffy, Foley, et al., 2012; Hernandez, Foley, & Beitin, 2011).

Even though the above-mentioned studies were conducted across a range of different professions, persons working in the education and health sector perceive a calling more often than those in other professions (Farkas, Johnson, & Foleno, 2000; Hagmaier & Abele, 2012). Teaching profession is, the same as a calling, characterized by a sense of personal mission, purpose in life and service towards others while most of the working time is spent in interactions with others (Dobrow, 2004; Saraf & Murthy, 2016; Wrzesniewski et al., 1997). Moreover, teachers with the calling orientation are more enthusiastic towards their work (e.g., Buskist, Benson, & Sikorski, 2005), more satisfied with their job and life (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997), more caring for their students’ well-being (Bullough & Hall-Kenyon, 2012), more engaged at work, perceiving their work as more meaningful, as a service for the greater good (Fouche, Rothmann, & van der Vyver, 2017; Rothmann & Hamukangandu, 2013a; Willemse & Deacon, 2015). Croatian elementary school teachers, who perceive teaching as a calling tend to be happier, more satisfied with their job and life, find more meaning in life, and have a lower level of emotional exhaustion (e.g., Jurčec, 2014; Jurčec & Rijavec, 2015). Nonetheless, it seems that the association between the calling orientation and these positive outcomes, especially well-being, is not so straightforward. Lately, scholars have focused on identifying potential mediators as the mechanisms which may explain that relationship (for a review, see Duffy et al., 2018). For instance, in one study among Croatian teachers (Miljković, Jurčec, & Rijavec, 2016) it was found that the relationship between the calling orientation and well-being was completely mediated by the meaningfulness of work and occupational identification while the relationship between the job orientation and well-being was only partially mediated by these variables.

Flow

Flow or optimal experience is a highly enjoyable state of effortless concentration during which a person is so involved in the activity that he/ she becomes completely absorbed in it (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). The preconditions necessary to enter a state of flow include a challenge – skill balance; specific and proximal goals; and clear and immediate feedback about the progress (Asakawa, 2010; Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002). As an intrinsically rewarding and enjoying experience, flow may occur during a variety of activities, such as playing instruments, dancing, climbing, playing chess, or working (Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi, 1988). What is crucial in achieving the flow state is that a person’s skills and challenges of a task are both at a high level. Studies showed that work is more flow-promoting than both leisure and maintenance activities (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, 1989). Nonetheless, Rijavec and colleagues (Rijavec, Ljubin-Golub, & Olčar, 2016) extended those findings with the notion that the flow experienced in the activities which a person perceives as most important contributes the most to his/her well-being. Teachers have been found to rather frequently experience flow at work (Delle Fave, 2007). For instance, primary school teachers who participated in a study reported by Beard and Hoy (2010) described experiencing the action - awareness merging, with the activities becoming spontaneous and automatic, and self-consciousness disappears during teachings, which are standard characteristics of experiencing flow. In another qualitative study (Dalton, Holoboff, Kaniusis, Kranenborg, & Sliva, 2014) five main characteristics emerged in teachers’ descriptions of flow: engagement, authentic and meaningful experiences, relationships, learning environment, flexibility and risk-taking. Finally, it is important to emphasize that in the state of flow, enjoyment in teaching is high and therefore teachers' enthusiasm and passion may become contagious for their students as well (Chan, 2009). Moreover, Csikszentmihalyi (1996) claimed that motivation provided by teachers' experience of flow may be crucial to effective teaching.

Studies have shown that flow is associated with higher engagement (e.g., Ljubin-Golub, Rijavec, & Jurčec, 2018), task interest, and job performance (e.g., Chu & Lee, 2012), life satisfaction (e.g., Asakawa, 2010) and psychological well-being (Bassi, Steca, Monzani, Greco, & Delle Fave, 2013). On the sample of Croatian primary school teachers, Olčar (2015) found that they often experience flow at work, mostly during teaching (63%) and that work-related flow was positively related to their well-being (positive affect, engagement and life satisfaction) and negatively to their ill-being (negative affect and burnout).

Problem Statement

According to recent studies, teachers’ well-being is a significant contributor to teacher effectiveness in terms of students’ academic achievement, so it would be worth finding out what contributes to teachers’ well-being. Even though the calling orientation is related to positive work outcomes and well-being, it seems that mere presence of calling is not sufficient to generate these outcomes (e.g., Duffy, England, Douglass, Autin & Allan, 2017; Duffy, Douglass, Autin, England, & Dik, 2016; Gazica & Spector, 2015).

As a reaction to the lack of theoretical framework that can define and conceptually clarify calling and the mechanisms through which it influences key outcomes, in their recent paper Duffy and his colleagues (Duffy, Dik, Douglass, England, & Velez, 2018) proposed a theoretical and empirically testable model called the Work as Calling Theory (WCT). Inter alia, they differentiated the terms

Whereas most of the aforementioned research explored teacher’s job and life satisfaction, this study deals with flourishing, as a concept that integrates hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in the sense of feeling good and functioning psychologically and socially well (Keyes, 2002), as the main criterion determining teachers’ well- being.

Research Questions

The main objective of this study is to examine the relationship between teachers’ work orientations and flourishing with the mediation of flow in different life domains. This study aims to answer: 1. How well can teachers’ flourishing be predicted by different work orientations?, 2. To what extent do flows in various life domains mediate the relationship between different work orientations and flourishing?

Purpose of the Study

By extending previous research that revealed a positive relationship between calling orientation and well-being, and negative job/career orientation and well-being, the current study aimed to explore the role of flow in different life domains as a mechanism underlying this relationship, with the emphasis on flow at work. Through the hypothesized model which integrates the two theories - the Theory of the Work as Calling and the Flow theory - an attempt has been made to explore and explain the teachers’ well-being.

Research Methods

The correlational research design was used to examine relationships between work orientations, flow in different life domains and teachers’ flourishing.

Participants and Procedure

The participants were 315 classroom teachers (teaching 1st to 4th primary school grades) from Croatia, mostly female (95 %). The number of years of teaching experience ranged from 0 to 43 years with a mean of 21 years (M = 21.21, SD = 11.68).

Questionnaires were administered during the professional meeting of primary school teachers at the county level and their completion lasted approximately 20 minutes. Prior to the questioning, the respondents were introduced to the aim of the study, and the researchers emphasized the significance of providing honest answers. Participation in the study was anonymous and voluntary.

Instruments

The following self-report instruments were used: Work-Life Questionnaire as a measure of work orientations, Swedish Flow Proneness Questionnaire, and Flourishing Scale as a measure of well-being.

Extracts from the scenarios (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997, p. 24):

Person A (job orientation) works primarily to earn enough money to support his life outside of his job. If he was financially secure, he would no longer continue with his current line of work, but would rather do something else instead.

Person B (career orientation) basically enjoys his work but does not expect to be in his current job five years from now. Instead, he plans to move on to a better, higher-level job. He has several professional goals for his future.

Person C’s (calling orientation) work is one of the most important parts of his life. He is very pleased that he is in this line of work. He tends to take his work home with him and on vacations, too. He is very satisfied with his work and feels good about his work because he loves it, and because he thinks it makes the world a better place.

Wrzesniewski and associates (1997) who also developed 18 true - false items questionnaire measuring the three orientations, revealed significant and substantial correlations of items with their corresponding scenarios. A translated version of WLQ was already used and showed adequate psychometric characteristics on the Croatian sample (Miljković et al., 2016).

The questionnaire showed adequate psychometric characteristics for each domain used in the original study (Ullen et al., 2012) as in the previous study on the Croatian sample (Rijavec et al., 2017). In the present study, Cronbach´s alpha coefficients of reliability were: .70, .74. and .77 for work, household maintenance activities and leisure time, respectively.

Findings

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., IL). Descriptive statistics were used to describe characteristics of Croatian teachers in this study. Correlations between the measured variables were assessed by the Pearson correlation coefficient. Three parallel mediation analyses using the PROCESS macro for SPSS were performed to test the hypothesized mediation role of flow in different life domains in the relationship between different work orientations and flourishing.

The underlying assumptions of multiple regression analysis were tested to ensure the validity of the results obtained. For most variables, the values of skewness and kurtosis were below +1 and above -1, except for the variable job orientations, for which kurtosis was below +2 and above -2, which is still considered acceptable confirming normal univariate distribution (George & Mallery, 2010). Mahalanobis' distance based on a chi-square distribution was calculated to detect multivariate outliers. The results showed that from the initial 320 participants, there were 5 cases determined to be multivariate outliers, and those cases were removed from further analysis. All predictors showed a variance inflation factor (VIF) well below the threshold of 5 indicating that multicollinearity was not an issue (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2014). All instruments used in the research showed adequate reliability in terms of Cronbach's alpha (see Instruments).

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive statistics and inter-correlations of all measured variables are presented in Table

As expected, the correlation between job orientation and calling orientation was negative, as well as the correlation between job orientation and flow at work (Table

Mediating Role of Flow in Different Domains in the Relationship Between Work Orientations and Flourishing

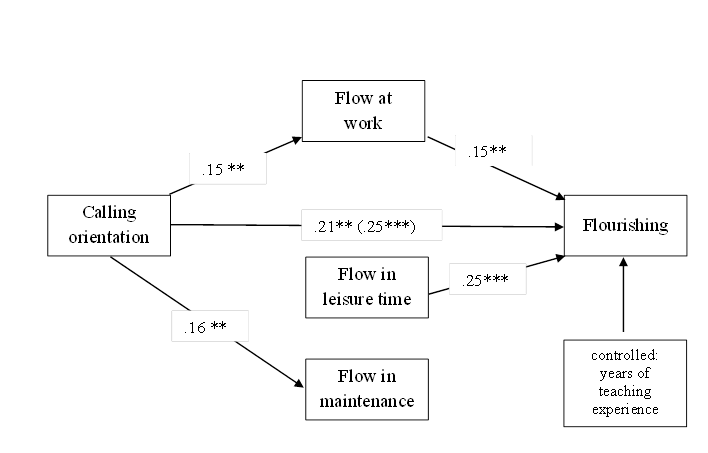

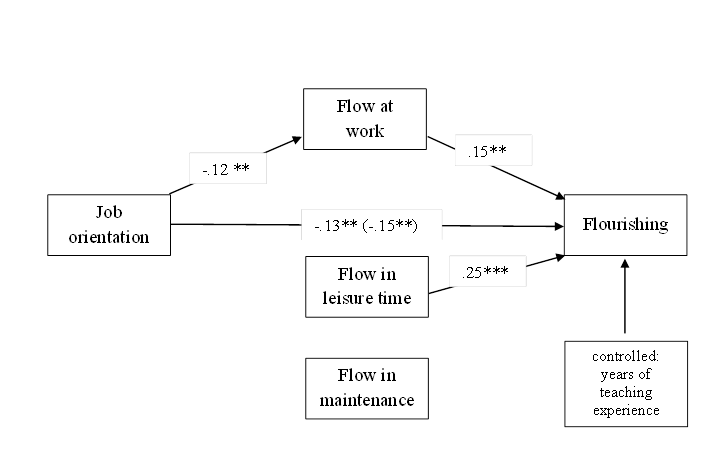

Three parallel mediation analyses were performed to test the hypothesized mediation role of flow in different life domains in the relation between work orientations and flourishing. A Monte-Carlo (bootstrapping) approximation was obtained with 2000 bootstrap resamples (the 95% confidence). Three models tested flow in different domains as mediators between calling and flourishing (Figure

Results of the mediation analysis (Figure

As Figure

Results for career orientation suggested that it was not significantly associated with teachers’ flourishing (

Conclusion

Job and calling orientation were related to well-being in an expected direction. Flourishing was positively linked to calling orientation and negatively to job orientation. These findings support the results of previous research with Croatian primary school teachers (Jurčec, 2014; Jurčec & Rijavec, 2015; Miljković et al., 2016) and other professions worldwide showing positive relationship between calling orientation and well-being (Duffy, Allan, Autin, & Bott, 2013; Duffy & Sedlacek, 2010; Peterson et al., 2009; Wrzesniewski et al., 1997) and negative relationship between job orientation and well-being (Wrzesniewski et al., 1997). Career orientation was not related to teachers’ well-being.

Results of parallel mediation analyses showed that calling orientation was positively linked to flow at work and to flow in maintenance. Job orientation was linked only to flow at work, in a negative direction while career orientation was not related to any of the flow domains. Flow at work and flow in leisure time (equally rated) were positively linked to flourishing, which is partially in line with previous studies indicating that work is more flow promoting than both leisure and maintenance activities (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, 1989). In their study on teachers and physicians, Delle Fave and Massimini (2003) found that highly structured leisure activities such as art-related hobbies and sports were selected as the outstanding opportunities for pervasive flow experiences. They concluded that their participants, according to Parker's description (1997), showed the extension pattern deriving from the spill-over approach in mutual influences between work and leisure in terms of skill development and levels of satisfaction between these different areas of life. Since flow in leisure activities had the strongest predictive power, its great potential in this domain for teachers’ flourishing can be emphasized. Unexpectedly, calling orientation was linked to the flow in household maintenance. It can only be assumed that teachers with calling orientation, through household maintenance felt purposeful, like contributors to the family life even though flow proneness in that domain does not provide an opportunity to flourish.

Calling orientation and job orientation have both direct and indirect effects on well-being, but in the opposite direction. Viewing one’s job as a calling increases work-related flow, which in turn makes teachers prone to flourishing. On the other hand, viewing their job solely as a source of financial security prevents them from experiencing work-related flow, which decreases the opportunity to flourish. Previous research results were contradictory regarding the correlations between career orientation and the other two orientations as well as its effect on teachers’ well-being. In one study on Croatian primary school teachers, career orientation was negatively correlated to job orientation and positively to calling orientation, job satisfaction and life satisfaction (Jurčec & Rijavec, 2015), while in other studies on a different sample of primary school teachers, career orientation was positively related to job orientation and negatively to calling orientation with no effect on job and life satisfaction (Miljković et al., 2016; Rijavec, Pečjak, Jurčec, & Gradišek, 2016). In the study by Rijavec and colleagues (2016), cluster analysis identified two clusters of teachers with different work orientation profiles: intrinsically oriented (higher calling orientation - lower job/career orientation) and extrinsically oriented teachers (lower calling orientation - higher job/career orientation) and the results revealed that intrinsically oriented teachers had higher level of job satisfaction. This was consistent with the framework of the Self-Determination Theory (SDT, Kasser & Ryan, 2001) as job and career orientations correspond to extrinsic life aspirations (financial benefits and status) while the calling orientation corresponds to intrinsic aspirations (such as community service, personal growth). Preferences of extrinsic rewards are connected to lower job and life satisfaction (Vansteenkiste et al., 2007), as confirmed in the present study regarding only job oriented teachers. Career orientation seems to be irrelevant to teachers’ flow proneness and well-being. A recent study by Olčar, Rijavec, and Ljubin Golub (2019) showed, through a serial mediation model, that pursuing extrinsic goals leads to lower well-being, mediated by lower autonomy and lower flow at work, while pursuing intrinsic goals leads to higher well-being, mediated through higher competence and flow at work. These empirical findings can bring some relevant practical implications for educational practice and teachers' well-being.

Practical Implications

This study has several practical implications. First, the results have confirmed that teachers with calling orientation have higher well-being than those with job or career orientation. This finding is important for career counsellors and persons aiming to become teachers because they should be aware of the potentially harmful effects of job orientation. Work orientations are comprised of work attitudes and ethics, and could thus be taken into account in teacher recruitment and evaluation. Those who already are in the teaching profession, but without perceiving or living a calling, should attend coaching and workshops that can help them bring meaning and purpose into their work and consequently find their calling (e.g., Dik, Duffy, & Eldridge, 2009).). There are also ways in which employees can re-craft their work (Berg, Dutton, & Wrzesniewski, 2008). Therefore, the school and educational policies need to provide space for teachers to craft their work. Second, the results revealed that flow can be a possible mechanism for the relationship between calling and well-being, thus suggesting that the flourishing of calling oriented teachers can be enhanced by assuring conditions for flow proneness at work. Creating a flow prone work environment that helps teachers to flourish can increase creativity, productivity and mutual student-teacher satisfaction in the classroom. To do so, some preconditions have to be met such as allowing autonomy through freedom and flexibility within a teachers' work role, competence through professional development programmes and relatedness through supportive school climate. In sum, to enhance teachers’ flourishing, an optimal balance between skill and challenge needs to be fostered and basic psychological needs satisfied (e.g., Olčar et al., 2019).

Limitation of the study

The study has several limitations. First, the collected data were based on self-report measures. Future studies may use other measures derived from qualitative methods such as observation, interviews, diary method, and the experience sampling method (ESM). Second, since the correlational and cross-sectional design was used, the temporal and causal inference could not be made. Future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the results of this study. Nevertheless, the present study is to authors’ knowledge the first to link teachers' calling with the flow at work, within the frame of their flourishing.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the grant of the University of Zagreb.

References

- Asakawa, K. (2010). Flow experience, culture, and well-being: How do autotelic Japanese college students feel, behave, and think in their daily lives? Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 205–223.

- Bakker, A. B. (2005). Flow among music teachers and their students: The crossover of peak experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 26-44.

- Bassi, M., Steca, P., Monzani, D., Greco, A., & Delle Fave, A. (2013). Personality and optimal experience in adolescence: Implications for well-being and development. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 829-843.

- Beard, K. S., & Hoy, W. K. (2010). The nature, meaning, and measure of teacher flow in elementary schools: A test of rival hypotheses. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(3), 426-458.

- Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. New York: Harper & Row.

- Berg, J., Dutton, J., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2008). What is job crafting and why does it matter? Retrieved on 18 April, 2019 from https://positiveorgs.bus.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/What-is-Job-Crafting-and-Why-Does-it-Matter1.pdf

- Briner, R., & Dewberry, C. (2007). Staff wellbeing is key to school success. A research study into the links between staff wellbeing and school performance. London: Worklife Support.

- Bullough, R. V., & Hall-Kenyon, K. (2012). On teacher hope, sense of calling, and commitment to teaching. Teacher Education Quarterly, 39(2), 7-27

- Bunderson, J. S., & Thompson, J. A. (2009). The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double-edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(1), 32-57.

- Buskist, W., Benson, T., & Sikorski, J. F. (2005). The call to teach. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(1), 111-122.

- Chan, D. W. (2009). Orientations to happiness and subjective well-being among Chinese prospective and in-service teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 29(2), 139-151.

- Chu, L., & Lee, C. (2012). Exploring the impact of flow experience on job performance. The Journal of Global Business, 8(2), 150-158.

- Clinton, M. E., Conway, N., & Sturges, J. (2017). “It’s tough hanging-up a call”: The relationships between calling and work hours, psychological detachment, sleep quality, and morning vigor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(1), 28-39.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper and Row.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York Harper Collins.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal Experience in Work and Leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 815-822.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, I. (1988). Optimal experience. Psychologicalstudies of flow in consciousness. Cambridge Univ Press.

- Dalton, A., Holoboff, J., Kaniusis, C., Kranenborg, S., & Sliva, J. (2014). Going with the 'Flow': Teachers' perspectives about when things really work. Online submission. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED545553.pdf

- Delle Fave, A. (2007). Ottimizzare l’esperienza di docenti e studenti. Teorie,ricerche, proposte [optimizing the experience of teachers and students.Theories, research, proposals]. In C. Cosimo & G. Vernì (Eds.), Scuolaattraente e cultural del benessere. La scuola che promuove salute (pp.27–70). Ufficio Scolastico Regionale Puglia: Bar

- Delle Fave, A., & Massimini, F. (2003). Optimal experience in work and leisure among teachers and physicians: Individual and bio-cultural implications. Leisure Studies, 22, 323-342.

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247-266.

- Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Eldridge, B. M. (2009). Calling and vocation in career counseling: Recommendations for promoting meaningful work. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(6), 625-632.

- Dik, B. J., Eldridge, B. M., Steger, M. F., & Duffy, R. D. (2012) Development and Validation of the Calling and Vocation Questionnaire (CVQ) and Brief Calling Scale (BCS). Journal of Career Assessment, 20, 242-263.

- Dobrow, S. (2004). Extreme subjective career success: A new integrated view of having a calling. Academy of Management Conference Best Paper Proceedings, Philadelphia. Retrieved from http://www.bnet.fordham.edu/dobrow/Papers.html

- Dobrow, S. R. (2006). Having a calling: A longitudinal study of young musicians. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Harvard University.

- Dobrow, S. R., & Tosti-Kharas, J. (2011). Calling: the Development of a Scale Measure. Personnel Psychology, 64, 1001-1049.

- Duffy, R. D., & Dik, B. J. (2013). Research on calling: What have we learned and where are we going? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 428-436.

- Duffy, R. D., & Sedlacek, W. E. (2010). The salience of a career calling among college students: Exploring group differences and links to religiousness, life meaning, and life satisfaction. The Career Development Quarterly, 59(1), 27-41.

- Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., & Bott, E. M. (2012). Calling and life satisfaction among undergraduate students: Investigating mediators and moderators. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 13(3), 469-479.

- Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., Autin, K. L., & Bott, E. M. (2013). Calling and life satisfaction: It’s not about having it, it’s about living it. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 42–52.

- Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., Autin, K. L., & Douglass, R. P. (2014). Living a calling and work well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(4), 605-615.

- Duffy, R. D., Bott, E. B., Allan, B. A., Torrey, C. L., & Dik, B. J. (2012). Perceiving a calling, living a calling,and job satisfaction: Testing a moderated, multiple mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59, 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026129

- Duffy, R. D., Dik, B. J., Douglass, R. P., England, J. W., & Velez, B. L. (2018). Work as a calling: A theoretical model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(4), 423-439.

- Duffy, R. D., Douglass, R. P., Autin, K. L., England, J., & Dik, B. J. (2016). Does the dark side of a calling exist? Examining potential negative effects. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(6), 634-646.

- Duffy, R. D., England, J. W., Douglass, R. P., Autin, K. A., & Allan, B. A. (2017). Perceiving a calling and well-being: Motivation and access to opportunity as moderators. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 127–137.

- Duffy, R. D., Foley, P. F., Raque-Bogdan, T. L., Reid-Marks, L., Dik, B. J., Castano, M. C., & Adams, C. M. (2012). Counseling psychologists who view their careers as a calling: A qualitative study. Journal of Career Assessment, 20, 293–308.

- Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 540–547.

- Farkas, S., Johnson, J., & Foleno, T. (2000). A sense of calling: Who teaches and why. New York: Public Agenda.

- Fouche, E., Rothmann, S., & van der Vyver, C. (2017). Antecedents and Outcomes of Meaningful Work among School Teachers. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 43, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v43i0.1398

- Gazica, M. W., & Spector, P. E. (2015). A comparison of individuals with unanswered callings to those with no calling at all. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 1-10.

- George, D., & Mallery, M. (2010). SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference (17.0 update). Boston: Pearson.

- Hagmaier, T., & Abele, A. E. (2012). The multidimensionality of calling: Conceptualization, measurement and a bicultural perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(1), 39-51.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Hall, D. T., & Chandler, D. E. (2005). Psychological success: When the career is a calling. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 155-176.

- Hernandez, E. F., Foley, P. F., & Beitin, B. K. (2011). Hearing the call: A phenomenological study of religion in career choice. Journal of Career Development, 38(1), 62-88.

- Hirschi, A. (2012). Callings and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of workmeaningfulness, occupational identity, and occupational self-efficacy. Journal of CounselingPsychology, 59(3), 479-485.

- Ihtiyaroğlu, N. (2018). Analyzing the Relationship between Happiness, Teachers' Level of Satisfaction with Life and Classroom Management Profiles. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(10), 2227 - 2237.

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79, 491-525.

- Jung, H. S., & Yoon, H. H. (2016). What does work meaning to hospitality employees? The effects of meaningful work on employees’ organizational commitment: The mediating role of job engagement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 59-68.

- Jurčec, L. (2014). Work orientations and teachers’ subjective well-being: mediating role of basic psychological needs and meaning in life. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Faculty of teacher education, University of Zagreb, Croatia.

- Jurčec, L., & Rijavec, M. (2015). Work orientations and well/ill-being of elementary school teachers. The Faculty of Teacher Education University of Zagreb Conference – Researching Paradigms of Childhood and Education – UFZG2015, Opatija, Croatia, 100-110.

- Kahn, W. A., & Fellows, S. (2013). Employee engagement and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 105-126). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

- Kaminsky, S. E., & Behrend, T. S. (2015). Career choice and calling: Integrating calling and social cognitive career theory. Journal of Career Assessment, 23, 383-398.

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Be careful what you wish for: Optimal functioning and the relative attainment of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. In P. Schmuck & K. M. Sheldon (Eds.), Life goals and well-being (pp. 116–131). Seattle, Toronto, Bern, Gottingen: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The Mental Health Continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207-222.

- Lee, A. Y. P., Chen, I. H., & Chang, P. C. (2016). Sense of calling in the workplace: The moderating effect of supportive organizational climate in Taiwanese organizations. Journal of Management & Organization. Advance online publication.

- Ljubin-Golub, T., Rijavec, M. & Jurčec, L. (2018). Flow in the academic domain: The role of perfectionism and engagement. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27(2), 99-107.

- McCallum, F., Price, D., Graham, A., & Morrison, A. (2017). Teacher wellbeing: a review of the literature. AISNSW Education Research Council. The University of Adelaide, South Australia.

- Miljković, D., Jurčec, L., & Rijavec, M. (2016). The relationship between teachers’ work orientations and well-being: mediating effects of work meaningfulness and occupational identification. In Z. Marković, M. Đurišić Bojanović & G. Đigić (Eds.), Individual and Environment: International Thematic Proceedia (pp. 303-312). Niš, Serbia: Faculty of Philosophy.

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89-105). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

- Olčar, D. (2015). Teachers’ Life Goals and well-being: mediating role of basic psychological needs and flow. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Faculty of teacher education, University of Zagreb, Croatia.

- Olčar, D., Rijavec, M., & Ljubin-Golub, T. (2019). Teachers' life satisfaction: the role of life goals, basic psychological needs and flow at work. Current Psychology, 38(2), 320-329.

- Park, J., Sohn, Y. W., & Ha, Y. J. (2016). South Korean salespersons’ calling, job performance, and organizational citizenship behavior the mediating role of occupational self-efficacy. Journal of Career Assessment, 24, 415– 428.

- Parker, S. (1997). Work and leisure futures: trends and scenarios. In J. T. Haworth (Ed.), Work, Leisure, and Well-being (pp. 180–191). London: Routledge.

- Peterson, C., Park, N., Hall, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Zest and work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(2), 161-172.

- Rawat, A., & Nadavulakere, S. (2015). Examining the outcomes of having a calling: Does context matter? Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(3), 499-512.

- Rijavec, M., Ljubin-Golub, T., & Olčar, D. (2016). Can learning for exams make students happy? Faculty related and faculty unrelated flow experiences and well-being. Croatian Journal of Education, 18(1), 153–164.

- Rijavec, M., Ljubin-Golub, T., Jurčec, L., & Olčar, D. (2017). Working part-time during studies: the role of flow in students’ well-being and academic achievement. Croatian Journal of Education, Sp.Ed. 19(3), 157-175.

- Rijavec, M., Pečjak, S., Jurčec, L., & Gradišek, P. (2016). Money and Career or Calling? Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Work Orientations and Job Satisfaction of Croatian and Slovenian Teachers. Croatian Journal of Education, 18(1), 201-223.

- Rothmann, S., & Hamukangandu, L. (2013a). Callings, work role fit psychological meaningfulness and work engagement among teachers in Zambia. South African Journal of Education, 33(2), 1-16.

- Rothmann, S., & Hamukangandu, L. (2013b). Psychological meaningfulness and work engagement among educators of Zambia. South African Journal of Education, 33, 1-16.

- Saraf, P., & Murthy, V. (2016). ‘Calling Work Orientation’ and Psychological Well Being among Teachers. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 3(3).

- Sawhney, G., Britt, T. W., & Wilson, C. (2019). Perceiving a Calling as a Predictor of Future Work Attitudes: The Moderating Role of Meaningful Work. Journal of Career Assessment.

- Sisask, M., Värnik, P., Värnik, A., Apter, A., Balazs, J., Balint, M., … Wasserman, D. (2014). Teacher satisfaction with school and psychological well-being affects their readiness to help children with mental health problems. Health Educ. J., 73(4), 382–393.

- Steger, M. F. (2017). Creating meaning and purpose at work. In L. Oades, M. Steger, A. Delle Fave, & J. Passmore (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of the psychology of positivity and strengths-based approaches at work (pp. 60-81).

- Sutton, R. E., & Wheatley, K. F. (2003). Teachers' Emotions and Teaching: A Review of the Literature and Directions for Future Research. Educational Psychology Review, 15(4), 327-358.

- Treadgold, R. (1999). Transcendent Vocations: Their Relationship to Stress, Depression, and Clarity of Self-Concept. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 39(1), 81-105.

- Ullen, F., de Manzano, O., Almeida, R., Magnusson, P. K. E., Pedersen, N. L., Nakamura, J., ... Madison, G. (2012). Proneness for psychological flow in everyday life: associations with personality and intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 167-172.

- Vansteenkiste, M., Neyrinck, B., Niemic, C., Soenens, B., De Witte, H., & Van den Broeck, A. (2007). Examining the relations among extrinsic versus intrinsic work value orientations, basic need satisfaction, and job experience: A Self-Determination Theory approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80, 251-277.

- Walsh, L. C., Boehm, J. K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2018). Does happiness promote career success? Revisiting the evidence. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(2), 199-219.

- Willemse, M., & Deacon, E. (2015). Experiencing a sense of calling: The influence of meaningful work on teachers’ work attitudes. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 41(1), 1-10.

- Wrzesniewski, A. (2003). Finding Positive Meaning in Work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline, (pp. 296-308). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C. R., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and callings: people’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 21–33.

- Xie, B., Xia, M., Xin, X., & Zhou, W. (2016). Linking calling to work engagement and subjective career success: The perspective of career construction theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 70-78.

- Zhang, C., Hirschi, A., Herrmann, A., Wei, J., & Zhang, J. (2015). Selfdirected career attitude as predictor of career and life satisfaction in Chinese employees. Career Development International, 20(7), 703-716.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

07 November 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-071-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

72

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-794

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Jurcec, L. (2019). Teachers’ Work Orientations And Flourishing: Mediated By Flow In Different Domains. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2019: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 72. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 40-56). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.11.4