Abstract

Globalisation has led to changing identities and relations between inner and outside worlds. The factors mediating in this exchange are languages and cultures. Bilingual young learners (YLs) develop their identity negotiating between the native and target language culture. They experience it in learning/teaching materials where meaning is communicated through verbal and visual modes. The project aims to investigate identity representations advocated in English language teaching (ELT) materials as the semiotic reality for YLs. Two major questions are designated:

Keywords: ELT materialsmultimodalitycultureidentityyoung learners

Introduction

Both global and local factors influence the teaching of English in Europe and worldwide such as the international and national policy of language education, ELT materials and teachers’ qualifications (Enever & Lopriore, 2014). YLs participate in a multimodally constituted world from an early age and are exposed to the native (or target) language in diverse conditions. In this paper, the term ‘YLs’ is applied to children in the first stage of education (the 1st, the 2nd and 3rd grade of primary school). Although the time and years dedicated to their English education varies from country to country, their language experience can be positive and result in the development of intercultural or even multimodal identity (Block, 2014; Bland, 2015). Since little attention has been given to MDA and materials, the project aims to investigate multimodal representations of identity included in printed ELT coursebooks for YLs as opposed to the actions they take (Block, 2014).

Contemporary conception of individual identity is dynamic in nature and depends on many factors (The current approach to identity involves definitions of both self-generated and imposed subject positioning by others. There are differences between the identity articulated by individuals (achieved or inhabited) and the identity given to a person by someone else (ascribed or attributed). Identity is a socially constructed, self-conscious and ongoing narrative interpreted and projected in dress, gesture, verbal and non-verbal language. These modes shape everyone who “develops” one’s identity in the context of the past, present and future with social, economic and cultural dimensions (Block, 2014,). Identity is never a complete process but an ongoing dialogue and split between “the Self” and “the Other”. It is seen as a meeting point of multiple discourses and complex cultural space needed for the construction of one’s identity (Holmes, 2014; Evans, 2016a). ) . Individuals (re)construct and (re)negotiate their identities every day through communication with others. They form identity during verbal and non-verbal interactions with local or foreign groups of people in which their stereotypes are challenged and confronted. The assumption in educational policy is that YLs should be able to understand their own identity to understand others. A dilemma is how to build learner’s identity for better understanding of oneself as well as others. Another dilemma is how to develop intercultural citizens who can act against social injustice and misinterpretation (Holmes, 2014). YLs’ experience languages and cultural conventions as interactions; they learn diverse social roles inside and outside of a classroom. The situation becomes even more complex for YLs who are simultaneously exposed to more than one language and often experience a multicultural environment (Kiss & Weninger, 2013).

YLs’ identity is described here in the frame of the post-structural approach as changing, complex and context-dependent. The post-structural theory of subjectivity (The post-structuralist theory of identity underlines the central role of language in the relationship between the individual and social context. It is the target language which defines one’s practices and helps to develop a sense of oneself defined as subjectivity (Norton, 2013; Kramsch, 2013). ) describes identity in applied linguistics with two questions: Who am I? What can I do? They indicate learners’ understanding of the world, learners’ identity development over time and space and their understanding of the future possibilities linked with English learning (Norton & Toohey, 2011; Norton, 2013). Language and identity research have always been an important field in applied linguistics (Norton, 2013). Language identity (Language identity involves three types of the relationships: language expertise (proficiency), language affiliation (attitude) and language inheritance (family setting). Each language is a cultural resource that reflects learner’s multi-dimensional identity and involves several aspects such as ethnicity, nationality, gender and social class (Block, 2014). The target language may also constrain the perception of social reality, the self or others (Chassy, 2016; Evans, 2016b). ) (ethnolinguistic identity) is defined as a relationship between one’s sense of self and the target language. YLs develop their identity across time, space and “invest” in English learning in specific settings. It is a sociological type of investment, perceived as the engagement in the target language education, linking learners’ desire and commitment (Norton & Toohey, 2011). With an increase of English proficiency, YLs develop a language ego and personality (Modern language education highlights three important issues linked with learners’ identity. The first is the cultural identity of the target language and pedagogy. The second is the cultural identity of the learner and the third is the dialectical interaction between these identities (Evans, 2016b). As previously stated, the early start of English education may initiate YLs’ development of (multi)intercultural identity together with educational progress and holistic development.) . Should the learners be bilinguals (multilinguals), they develop a perception of oneself in both (or 3-4) languages, a bilingual or multilingual identity respectively to become an inter(multi) cultural speaker. Identity can change as learners move from one language to another (Block, 2014; Kalaja & Melo-Pfeifer, 2019). There is a tendency to argue in favour of yet another identity type - a multimodal identity (Namely, English identity is defined through audibility involving the right accent and behaviour. To consider a multimodal dimension, audibility influences development of one’s identity in an additional language, including behaviours. For example, immigrant YLs in the UK are to present an acceptable multimodal set of accents, dress, gesture although they still may be foreigners. ) , developed not in addition to the language identity but as “a replacement for it” (van Leeuwen, 2009; Block, 2014). Following a multimodal perspective on identity, the target language is one mediator out of many mediators in the construction of identity (Previous studies relate to races represented in the images, frequency of their representation, manners of presenting cultures, and the context of portraying races. It has been proven that YLs acquire, interpret and use consciously (or unconsciously) the social, cultural, economic and racial realities depicted in the visual content (Taylor-Mendes, 2009). Namely, they can convey a vision of gender realities and social roles. The popular questions asked are about the activities in the image, the active or passive characters, the meaning of body language and clothes, and position of the characters’ eyes. Namely, images in the ELT coursebooks in America seem to reinforce a Hollywood version of culture and do not represent the real world. They avoid the historical consequences of colonization, migration and the mixing of race and identity. They reinforce the stereotypes in which race and culture are divided by continent, e.g. Asians live in Asia, Blacks in Africa, etc. (Taylor-Mendes, 2009; Hill, 2013).) (Block, 2014).

Identity and ELT materials

Identity is constructed in ELT coursebooks through verbal and visual content (The central idea of ELT materials is representation of English through content including people, places, activities and customs. Verbal and visual content have never been neutral as they represent a specific language, communication and culture, forming multimodal discourses. As Holmes states Language learning is no longer about food, festivals, facts and flags, but understanding culture as a social construction: learners are encouraged to understand how culture – their own and that of others - permeates and shapes behaviours, interactions and language choices. It also requires an understanding of their own identity and that of the others in this (intercultural) communicative process (Holmes, 2014, p.77-78).Cultural content is always designed in a frame, which defines what and how it will be represented (Gray, 2013; Kullman, 2013). ) . There is always a question of how ELT materials are to reflect identity, showing a diversity of English societies. The tendency is to show the white middle-class values in the context of BANA countries (Publishers who sell their products must be politically correct following Western values with a non-sexist approach to the way the female and male are presented (Gray, 2014; Gray & Block, 2014). The publishers follow the acronym PARSNIP (no politics, no alcohol, no religion, no sex, no narcotics, isms and pork) and avoid the subject areas related to anarchy, aids, Israel, six pointed stars, racism, science such as genetic engineering, terrorism and violence. ) . Cultural content in ELT materials for YLs includes simple identities such as family identities without the difficulties of family break-ups or stereotyped daily routines where characters perform similar tasks each day (Evans, 2016b). YLs in their early encounter with English experience ELT materials as sources of the target culture. ELT materials promote a sense of global (or local) identity (Byram’s model of intercultural knowledge, skills, behaviours and attitudes needed for the appropriate comprehension of others is applied in materials design in Europe (the CEFR in the EU) (Enever & Lapriore, 2014; Pulverness & Tomlinson, 2013). Since ELT materials in the form of coursebooks are still the norm in early language education (Rixon, 2015), their multimodal aspects should be investigated for educational implications. YLs are stimulated by texts and images that directly or indirectly deal with multicultural aspects. ELT materials provide opportunities for YLs to reflect on their native culture and learn about the target language culture, social practices and attitudes to other people. They can stress YLs’ personal reflection and develop a sense of pride in their native cultural identity (Driscoll, 2017).) (Hadley, 2014; Driscoll & Simpson, 2015). The idea is to develop ICC (intercultural communicative competence) which implies an ongoing process like development of YLs’ identity (ELT materials support development of a learner’s identity as the integral factor contributing to the YLs’ cultural development and their ability to function in a cultural “third place”. The third place is a space where a learner finds their own cultural meaning and adapts the language to their needs (Kramsch, 1993; Pulverness & Tomlinson, 2013).) (Driscoll & Simpson, 2015; Ibrahim, 2019).

English and images in the global coursebooks are “cosmopolitan”, modelling the discourse of a Western market. Global materials include titles that reflect English learning as a cross-cultural experience. Only coursebooks which are approved by the ministry of education can be used in schools, then it is assumed that they promote tolerance and good values (Richards, 2014). They are criticised for the discourses of cultural imperialism, individualism and consumerism with a focus on personal qualities, autonomy and learner-centeredness (It is depicted in ELT materials through stories, which imply specific behaviours or choices, forming a narrative profile) (Garton & Graves, 2014; Graves & Garton, 2014; Hadley, 2014). To integrate English and home language-and-culture, the solution can be locally produced glocal (global-plus-local) materials. The glocal ELT materials carry the representative view of home and target culture. They are kinds of country/region specific materials produced during projects, subject-specific and content-based materials (Pulverness & Tomlinson, 2013; Kiss & Weninger, 2013). The dilemma involves the representation of values and social behaviours included (or not) in verbal and non-verbal content. They are reflected in the following set of criteria and questions:

topics: what topics are included in ELT materials?

diversity of characters presented in ELT materials: what ethnic groups are presented?

treatment of gender: what roles are presented by male/ female characters?

treatment of age: how old are the characters in ELT materials?

treatment of roles: what roles do they represent in ELT materials?

language varieties: what English is presented? Who is speaking the dialects?

situations: what context/ actions are provided for male/female characters?

lifestyles: what kinds of lifestyles are depicted?

art: what kinds of images and visuals are used? (Richards, 2014).

The author of the paper will add one more category linked with a multimodal perspective:

visual-verbal modalities: what relationships are used between texts and images to influence identity development?

Multimodality of ELT materials

The multimodal perspective on meaning and communication has been widely investigated from the early 1990s (Bezemer & Jewitt, 2018). Multimodality is a socially founded semiotic theory with a focus on power, representation and communication described as

Multimodality is perceived as a resource for the expression of identity (Block, 2014, pp.1-3) while image-language relationships bring the data on the inner construction of content (The visual content is represented by various images, drawings, illustrations, photos, maps, icons, paintings, cartoons, diagrams and functional illustrations (Tomlinson & Masuhara, 2018). A tendency is to use images with a gender-neutral style, including all physical types of people, with only a few images of physical disability. The assumption is to avoid stereotypical pictures and controversial topics. They are to represent politically acceptable values with an idealised and middle-class view of world (Gray, 2013; Gray & Block, 2014; Richards, 2014). It is expected that both visual and verbal content is not supposed to form stereotypes. ELT materials for YLs include a vast number of images while testing and assessment in Polish education is based mainly on written forms (Danielsson & Selander 2016; Stec, 2016). Unfortunately, skills of visual literacy are not trained at school but are still very important in the social context to read multimodal texts (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006).) for identity representation. Each mode offers distinct potentials and constraints. A mode of language which is governed by the logic of time and sequence has unique possibilities as well as some limitations in making meaning. A mode of image is directed by the logic of space, organised arrangements, size, position and composition of the content (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996; Street, 2017; Bezemer & Jewitt, 2018). Meaning and messages are constructed (A unity made up of words and images in various artefacts, printed and online media, requires the shared roles of different modes to construct meaning and is defined as intermodality. Intermodality, multimodal strategies of communication and a multimodal perspective to research discourses are the important dimension of future education and research (Mills & Unsworth, 2016; Hodge, 2017; Jewitt, 2017). Intermodality can be analysed as a representational/ideational structure and compositional/textual meanings. A mode of image similarly to a mode of language has a “grammar” so our visual grammar will describe the way in which depicted elements – people, places and things combine in “visual statements” (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006, p.1). Communication may occur in and through the image as they inform and influence YLs. Then, visual literacy is needed to “read” multimodal texts (Kress, 2017; Jagodzinski, 2017). ) across time and space similarly to human experience, while interacting with other people or things (Lemke, 2017; Mavers, 2017).

However, this project follows the single or double-page layout as a unit of analysis and a frame defined as intermodal integration. The intermodal integration can have an integrated (projected, expanded) or complementary form of arrangement. To analyse the image, a system of framing is introduced, resulting in bound or unbound images with or without a frame (Mills & Unsworth, 2016, p.13-14; Painter, Martin & Unsworth, 2014). The frame plays two vital semiotic roles: to separate elements or to unite them in making meaning from a designer’s perspective. Then, visual literacy is needed to “read” multimodal texts (Kress, 2017; Jagodzinski, 2017). This paper follows Stȍckl’s framework with fours modes: sound, music, image and language and medial variants respectively (Stȍckl, 2004). This project focuses on a mode of language (These are static (still) and dynamic (moving) images or speech, static writing and animated writing for language. Language involves here static writing and the following sub modes: typography, layout, fonts, colours, ornaments, spacing and margins. .. Image is limited here only to static images with such sub-modes as elements, vectors, colour, lighting, size, distance, angle/perspective and composition. The framework is used widely in research on materials such as audio-visual translations (Perez-Gonzales, 2014).) and image. In recent years, there is a focus on the multimodal design of textbooks (The most popular research on materials focuses on the use of writing, image, and layout to generate meaning in educational materials. They follow the Western tradition of writing and space reading from left to right in terms of visual grammar) as different means of meaning making always appear together as a whole (Street, 2017; Bezemer & Jewitt, 2018). Their multimodality is based on left-right polarisation, integrated double-page layout, colours and symbols, bound and unbound images considering composition (Namely, there are analyses of children’s picture books, which are a “bimodal” or “bisemiotic” form of texts (Painter, Martin & Unsworth, 2014). The less popular are research on the use of materials or interpretation of their modes. ELT materials provide YLs with real-life cultural content, which can be used for modelling English (Gray, 2013; Driscoll & Simpson, 2015).) . ELT materials are interactive cultural artefacts that can be exploited either at the level of the page (materials as-they-are, the content and activities offered) and the level of implementation (materials-in-action) and results observed in a classroom. There are only a few projects related to visual content (Hill, 2013; Kiss & Weninger, 2013). Further research is designed to investigate the matter

Problem Statement

The key problem is the multimodality of ELT coursebooks for YLs and their multicultural content in the framework of identity. This research project follows a socio-cultural perspective (post-structural) on English and YLs’ identity. The focus is on the image-language relationship – intermodality as the interplay between verbal and non-verbal semiotics in the construction of cultural content with the impact on YLs’ identity.

Research Questions

Two major questions are addressed:

How do visual and verbal modalities reflect children’s identity in ELT coursebooks?

What is the image-text relationship in the cultural content for identity representation?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose is to investigate identity representations offered in ELT materials for YLs with an emphasis on multimodality. Multimodality involves here visual and verbal modalities forming the cultural content. The idea is to investigate image-text relationships following MDA and exploring a selection of topics and models of design.

Research Methods

The qualitative type of methods and procedures are used following the sociolinguistic approach (Norton, 2013; Evans, 2016a). The project is divided into two stages. ELT coursebooks are selected and coded respectively in the first stage, fulfilling a modified for this project list of criteria (A list includes (Tomlinson, 2013):

Glocal criteria: related to English language education in Europe and Poland.

Age-specific criteria: related to the age of the target learners (YLs).

Content specific criteria: related to the cultural content (home and English culture and child-related topics).

Multimodal criteria: related to the core modes of image and language and their sub-modes. ) . The second stage involves a more detailed analysis of image-text intermodality at the level of the page with the checklist entitled

Questions about concurrence related to the image-language agreement and correspondence in terms of clarification, exposition and exemplification.

Questions about complementarity related to the image-language supplement in terms of augmentation or divergence.

Questions about enhancement related to the image-language enrichment in terms of manner, condition and space. ) . Other questions deal with image-text relationship through layout, composition and framing. Finally, one question deals with the types of identities presented and one more is for extra comments on the matter (ELT Coursebook Evaluation for YLs: A Checklist for Identity and Multimodality of Cultural Content.

Introduction: users’ background information and selection of cultural content.

Please specify a group of YLs. Complete the sentences.

YLs are …

Their level of English is …

What cultural content is offered in the ELT coursebook?

Which topics are included?

What characters are represented?

What visuals are implemented?

What elements of language and communication are stressed?

What context is included for the presentation of verbal input?

How is the cultural content designed in terms of verbal modality (semiotics)?

How is the cultural content designed in terms of visual modality (semiotics)?

Multimodality of cultural content: image-language relations.

Check the cultural content and describe multimodality in terms of expansion.

What are the examples of concurrence (the image-language agreement and correspondence – clarification/exposition/exemplification)? …..

What are the examples of complementarity (the image-language supplement – augmentation/divergence)? ….

What are the examples of enhancement (the image-language enrichment – manner/ condition/space)? ….

What is the image-text relationship of cultural content in terms of layout?

What is the image-text relationship of cultural content in terms of composition?

What is the image-text relationship of cultural content in terms of framing?

What types of identity are reflected on the selected pages? ………

Other comments on the image-language relationship (please specify): ….) .

Since the project involves the process of coding, quantitative analysis and interpretation, the results are collected, recorded on charts and compared. The process requires a precise identification of feedback and analysis of data in stages.

Findings

After the selection, in total 12 ELT coursebooks for YLs from four series have been examined (The series include: “Incredible English” by S. Philips, K. Grainger, M. Morgan, M. Slattery, (Oxford, 2016), “Oxford Explorers” by Ch. Covill, M. Charrington, (Oxford: 2015), “English Quest” by J. Corbett, R. O’Farrell, M. Kondro (Macmillan, 2015), “My World” by J. Heath, D. Sikora-Banasik (Nowa Era, 2015). ) . The results were grouped and addressed in the categories respectively to a range of coursebooks.

Results from the 1st stage

Initially, the cultural content was selected from each coursebook following a category of topics and pages. This paper presents the results from the coursebooks addressed for the first year of primary school. The detailed results are presented in Table

As the table indicates, the cultural content is limited to three topic areas: “My family/My home/ My school”. There are twenty pages selected for the examination in each topic area except for “My home” area which is less representative and includes only ten pages in the selected coursebooks. Coursebooks entitled

Here, a sample of the results from

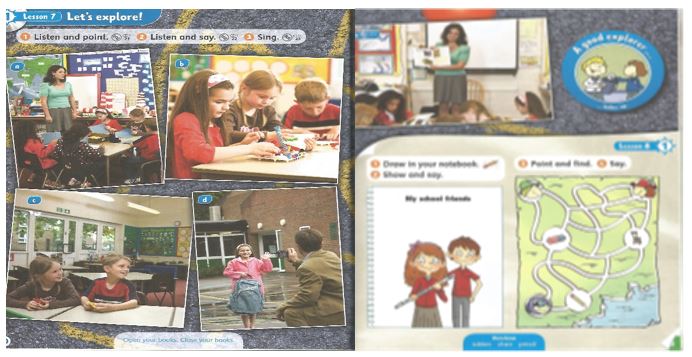

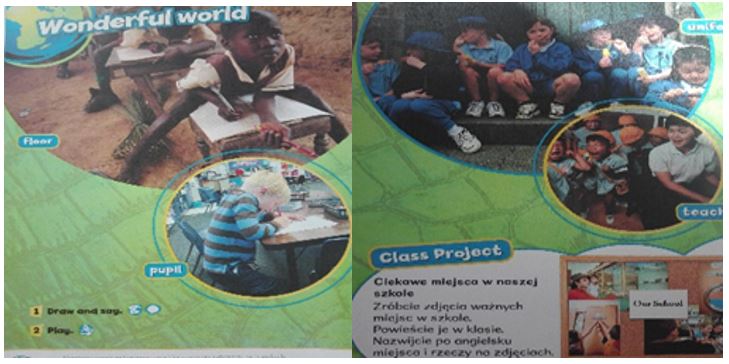

The results show unanimously that identity is developed through topics familiar to YLs depicted at home or in an international context with the help of representative but different characters accompanied by animals. A tendency is to present the middle-class white/Europeans, only a few with African and Asian origins, which is consistent with the previous studies on the matter. Contrary to expectations, the topical area such as “My school” includes older members of the family as it is a school show with invited guests (

Results from the second stage

The visual content includes CG drawings (computer-generated), icons and symbols easily navigated while authentic pictures are less popular (

The detailed analysis of the cultural content resulted in very interesting data. The image-language relationship provided understandings into the construction of the input offered for YLs. These are multimodal texts with the model sections. The sections vary in terms of images (simple or complex) and texts. For the purpose of this study, the results are classified in two categories: the expansion and projection of meanings. The expansion of meanings involves the subcategory of concurrence, complementarity and

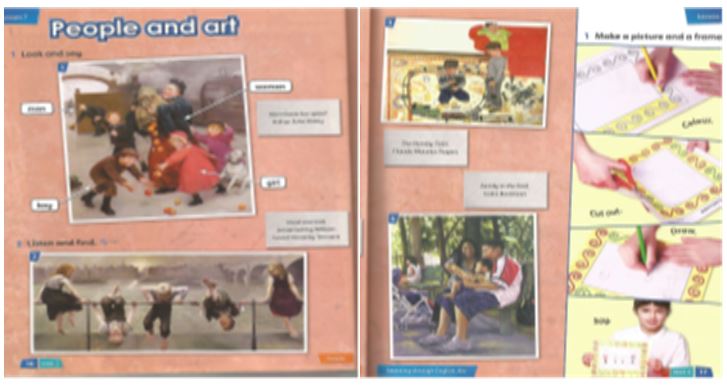

enhancement. A sample of the concurrence can be found in this research as presented in Figure

In Figure

The phenomenon to extend the topic of learning is depicted in Figure

Contrary to expectations, the school topic is realised with a focus on art, play and craft generating ideational meanings through pictures (YLs learn about children’s activities and games in past and modern times. There are four paintings exposed with their authors and titles. The first picture is used for the introduction of four basic words (woman, man, girl and boy). The visual content indicates here different perspectives on children’s forms of entertainment with or without adults’ participation. The project part of this section is related to the subject matter as YLs are to design a frame and draw a picture. It is a double-paged spread classified as the expansion of meaning, precisely the concurrence with exemplification when images instantiate texts with unbounded but contextualised framing. The modalities reflect here language, social and lifestyle as well as multicultural identity with elements of history caught in art.) . The findings of this study support the growing interest in multimodality and its impact on YLs’ development.

Conclusion

The present results are significant in at least two respects. First, visual and verbal modalities form a set of topics for carefully designed cultural content with characters presented in Polish and international contexts. The content relates to the topic areas familiar to YLs such as home, family or school. The findings also show that most characters in ELT coursebooks are middle-class white/Europeans with a few of African or Asian cultural origins. Considering the age factor, older people are depicted only as grandparents in the family topic. Animals, on the contrary, are always present as family members. The study confirms that disabled people are absent in ELT coursebooks. Context for the language presentation may vary -to start with a place such as an authentic classroom at home or abroad to an imaginary bedroom. Music as another mode accompanies the language introduction through songs or chants. The cultural content is two-dimensional: international (not limited to BANA countries only) and the native one.

The conclusion from the project is that YLs’ language identity is reflected in the cultural content through multimodal discourses, but mainly with the mode of picture, language and music. Visuals constructing in the cultural content influence YLs’ identity development through bright and colourful computer-generated pictures, drawings, images of real objects. Most of them are very detailed. The pages are easily navigated with the help of icons and symbols, forming a nice and clear layout, composition and framing. The results also confirm that the image-text relationships are established through an integrated layout, double-page spread and bimodal approach to visual and verbal content in materials design for YLs. English and images are designed to generate ideational meanings in ELT coursebooks for YLs such as expansion and concurrence favourably with exposition and exemplification. The results of this study support the idea that multimodal literacy is needed for reading various forms of contemporary texts. ELT materials should be analysed across two following pages for better comprehension of the content. It is settled that materials development should involve an analysis of ELT coursebooks as a visual-verbal unity.

The current investigation was limited by a sample size of ELT materials and partial analysis of data. Another weakness was linked with structure and agency issues such as the identity categories used (race, age, culture, social class), political and economic issues in global and glocal ELT materials in terms of power and knowledge. One more challenge was linked with a complete data presentation. Interests in English language education and identity development have been growing recently. In fact, the issue has been investigated with different methodologies and approaches, bringing various learners’ and teachers’ perspectives on the matter. It will be a good idea to explore which aspects of English culture are (not) presented in ELT coursebooks through visual and verbal content. Further research might examine visual images and their impact on learners’ view of English or their world. Finally, one more dilemma can be explored: whether we shall move (or not) towards an investigation of multimodal identities in the context of ELT education. Obviously, modern society needs skills in reading multimodal texts while simultaneously developing multilateral skills. Then, a multimodal perspective in the field of materials development is needed in future studies.

References

- Bezemer, J., & Jewitt, C. (2018). Multimodality: A Guide for Linguists. In: L. Litosseliti (Ed.), Research Methods in Linguistics (pp.281-304). London & New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Bland, J. (2015). Introduction. In: J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 Year Olds (pp.1-12). London & New York, Bloomsbury.

- Block, D. (2014). Second Language Identities. London & New York: Bloomsbury.

- Chassy, P. (2016). How Language Shapes Social Perception. In: D. Evans, (Ed.), Language and Identity. Discourse in the World (pp.36-54). London & New York: Bloomsbury.

- Danielsson, K., & Selander, S. (2016). Reading Multimodal Texts for Learning - a Model for Cultivating Multimodal Literacy. Design for Learning, 8(1), 25-36.

- Driscoll, P. (2017). Considering the Complexities of Teaching Intercultural Understanding in Foreign Languages. In: J. Enever, & E. Lindgren (Eds.), Early Language Learning (pp.24-40). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Driscoll, P., & Simpson, H. (2015). Developing Intercultural Understanding in Primary Schools. In: J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 Year Olds (pp.167-182). London & New York: Bloomsbury.

- Enever, J., & Lopriore, L. (2014). Language Learning across Borders and across Time: A Critical Appraisal of a Transnational, Longitudinal Model for Research Investigation. Elsevier System, 45,187-197.

- Evans, D. (2016a). The Identities of Language. In: D. Evans, (Ed.), Language and Identity. Discourse in the World (pp.15-35). London & New York: Bloomsbury.

- Evans, D. (2016b). Towards a Cultural Paradigm of Alterity in Modern Foreign Language (MFL) Learning. In: D. Evans, (Ed.), Language and Identity. Discourse in the World (pp.188-206). London & New York: Bloomsbury.

- Garton, S., & Graves, K. (2014). Materials in ELT: Current Issues. In: K. Graves, & S. Garton (Eds.), International Perspectives on Materials in ELT (pp.1-18). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grapin, S. (2019). Multimodality in the New Content Standards Era: Implications for English Learners. TESOL Q, 53, 30-55.

- Graves, K., & Garton, S. (2014). Materials and ELT: Looking Ahead. In: K. Graves, & S. Garton (Eds.), International Perspectives on Materials in ELT (pp.270-279). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gray, J. (2013). Introduction. In: J. Gray (Ed.), Critical Perspectives on Language Teaching Materials (pp.1-16). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gray, J., & Block, D. (2014). All Middle Class Now? Evolving Representations of the Working Class in the Neoliberal Era: The Case of ELT Textbooks. In: N. Harwood, (Ed.), English Language Teaching Textbooks. Content, Consumption, Production (pp.45-71). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hadley, G. (2014). Global Textbooks in Local Context: An Empirical Investigation of Effectiveness. In: N. Harwood, (Ed.), English Language Teaching Textbooks. Content, Consumption, Production (pp.205-240). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hill, D. A. (2013). The Visual Elements in EFL Coursebooks. In: B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing Materials for Language Teaching (pp.157-166). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Hodge, B. (2017). Kress on Kress: Using a Method to Read a Life. In: M. Böck & N. Pachler (Eds.), Multimodality and Social Semiosis. Communication, Meaning-Making, and Learning in the Work of Gunther Kress (pp.7-15). London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Holmes, P. (2014). The (Inter)Cultural Turn in Foreign Language Teaching. In: N. Pachler, & A. Redondo, (Eds.), A Practical Guide to Teaching Foreign Languages in the Secondary School (pp.76-86). London & New York: Routledge.

- Ibrahim, N. (2019). Children’s Multimodal Visual Narratives as Possible Sites of Identity Performance. In: P. Kalaja, & S. Melo-Pfeifer, (Eds.), Visualising Multilingual Lives. More than words (pp.33-52). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Jagodzinski, J. (2017). On the Problematics of Visual Imagery. In: M. Böck & N. Pachler (Eds.), Multimodality and Social Semiosis. Communication, Meaning-Making, and Learning in the Work of Gunther Kress (pp.71-78). London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jewitt, C. (2017). An Introduction to Multimodality. In: C. Jewitt, (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis (pp. 15-30). London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kalaja, P. & Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2019). Conclusion: Lessons Learnt with and Through Visual Narratives of Multilingualism as Lived, and a Research Agenda. In: P. Kalaja & S. Melo-Pfeifer (Eds.), Visualising Multilingual Lives. More than words, (pp.275-284). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Kiss, T. & Weninger, C. (2013). A Semiotic Exploration of Cultural Potential in ELT Textbooks. Malaysian Journal of ELT Research, 9/1. 19-28.

- Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Oxford: OUP.

- Kramsch, C. (2013). Afterword. In: B. Norton, (Ed.), Identity and Language Learning. Extending the Conversation (pp.192-198). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Kress, G. (2017). What is mode? In: C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis (pp.60-75). London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal Discourse. The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold, OUP.

- Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Psychology Press.

- Kullman, J. (2013). Telling Tales: Changing Discourses of Identity in the “Global” UK-Published English Language Coursebook. In: J. Gray (Ed.), Critical Perspectives on Language Teaching Materials (pp.17-39). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lemke, J. (2017). Multimodality, identity, and time. In: C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis (pp.165-175). London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Martinec, R., & Salway, A. (2005). A System for Image-Text Relations in New (and Old) Media. In: Visual Communication, 4(3). 338-371.

- Mavers, D. (2017). Semiotic Work in the Apparently Mundane: Completing a Structured Worksheet. In: M. Böck & N. Pachler (Eds.), Multimodality and Social Semiosis. Communication, Meaning-Making, and Learning in the Work of Gunther Kress (pp.175-182). London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mills, K., & Unsworth, L. (2016). Multimodal Literacy. Oxford Research Encyclopaedia, Education. Oxford: OUP. 1-32.

- Norton, B. (2013). Identity and Language Learning. Extending the Conversation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, Language Learning, and Social Change. Language Teaching, 44/4. 412-446. CUP.

- Painter, C., Martin, J. R., & Unsworth, L. (2014). Reading Visual Narratives. Image Analysis of Children’s Picture Books. Sheffield & Bristol: Equinox.

- Perez-Gonzales, L. (2014). Audio-visual Translation Theories, Methods and Issues. London & New York: Routledge.

- Pulverness, A., & Tomlinson, B. (2013). Materials for Cultural Awareness. In: B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing Materials for Language Teaching (pp.443-460). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Richards, J. C. (2014). Materials and ELT: Looking Ahead. In: K. Graves, S. Garton (Eds.), International Perspectives on Materials in ELT (pp.19-36). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rixon, S. (2015). Primary English and Critical Issues: A Worldwide Perspective. In: J. Bland (Ed.), Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3-12 Year Olds. (pp.31-50). London & New York, Bloomsbury.

- Stec, M. (2016). Ilustracja jako narzędzie w materiałach testujących znajomość języka angielskiego u dzieci. In: D. Gabryś-Barker, & R. Kalamarz (Eds.), Ocenianie i pomiar biegłości językowej: wybrane aspekty teoretyczne i praktyczne (pp.27-42). Katowice: Wyd. Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

- Stȍckl, H. (2004). In Between Modes. Language and Image in Printed media. In: E. Ventola, C. Charles, & M. Kaltenbacher, (eds). Perspectives on Multimodality, (pp.9-30). Amsterdam-Philadelphia.

- Stȍckl, H. (2017). Semantic Paradigm and Multimodality. In: C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis (pp.274-286). London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Street, B. (2017). Multimodality and New Literacy Studios. In: M. Böck & N. Pachler (Eds.), Multimodality and Social Semiosis. Communication, Meaning-Making, and Learning in the Work of Gunther Kress (pp.103-112). London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Taylor-Mendes, C. (2009). Construction of Racial Stereotypes in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Textbooks: Images as Discourse. In: R, Kubota, & A. Lin (Eds.), Race, Culture, and Identities in Second Language Education. Exploring Critically Engaged Practice (pp.64-80). New York & London: Routledge.

- Tomlinson, B. (2013). Materials evaluation. In: B. Tomlinson, (Ed.), Developing Materials for Language Teaching (pp.21-48). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2018). The Complete Guide to the Theory and Practice of Materials Development for Language Learning. New York: Wiley Blackwell.

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2009). Discourses of Identity. Language Teaching, 42/2, 212-221. I

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

07 November 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-071-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

72

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-794

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Stec, M. (2019). Identity And Multimodality Of Cultural Content In Elt Coursebooks For Yls. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2019: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 72. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 274-288). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.11.25