Abstract

The purpose of this exploratory descriptive research using a free-response methodology was to examine social pedagogues' definitions of learner-on-learner, learner-on-educator and educator-on-adult bullying in school context. This study is one of the first studies to approach to conceptualize three different types of bullying from the perspective of the social pedagogues. A representative sample of 165 social pedagogues provided their own definition about school bullying, educator-targeted bullying and educator-targeted workplace bullying. Quantitative content analysis revealed that the participants held a shared understanding of the three types of bullying concurred with those used in the research literature – intention, repetition, imbalance of power, and causing harm to victim. Although, these components remain a part of the definitions of three types of bullying, social pedagogues operated broader multilevel bullying definitions with adding two components – recognition of individuals engaging in bullying behavior and approaches for dealing with bullying. However, differences in the conceptualization of three types of bullying among social pedagogues were found as well. It was revealed that social pedagogues differentiated the meaning of three types of bullying from each other in terms of type of aggression, power relationship character, manifestations of workplace bullying forms, and characteristics of the individuals engaged in bullying. The one occupation-specific approach focusing on social pedagogues’ perspective can enhance our understanding of the multilevel conceptual nature of bullying in school context.

Keywords: School bullyingteacher-targeted bullyingworkplace bullyingdefinitions of bullyingsocial pedagogues’ perspective

Introduction

Most researchers (Monks & Coyne, 2011) consistently define bullying as repetitive aggressive behavior, with an intent to cause harm and an imbalance of power across lifetime (from preschool to elder age) in different social contexts (like school, prison, workplace) and relationships (e.g. families, dating relationships). The first and the most studied form of bullying in school contexts is learner-to-learner bullying - school bullying, occurring when one or more pupils engage in bullying behavior (e.g. Smith et al, 1999). There are two forms of bullying at schools in the educator-learner relationship – learner-on-educator bullying (also called educator-targeted bullying: De Wet, 2010) involving the bullying of an adult by a child; and educator-on-learner bullying as educators’ bullying toward learners.

A framework for the most widespread contemporary research definition of bullying integrating three criteria (intention to cause harm, a power imbalance, and repetition of aggression over time: Farrington 1993; Olweus, 1999) provides a more specific framework for definitions of bullying across the educator-learner relationship level. For example, educator-targeted bullying is aggression directed against individuals who guide learners’ social, cognitive and emotional development and provide security for them. Educator-targeted bullying include the three criteria: an imbalance of power between the aggressor (learner/s) and the educator; aggressive behavior is deliberate and repeated; and the aim of the aggression is to harm the victim physically, emotionally, socially and/or professionally (De Wet, 2010).

However, as learner-to-educator and educator-on-learner bullying occurs within the school context, the place of work for educators, workplace bullying of educators includes being bullied by and/or being victim of teachers, parents, administrative and other staff members (including non-teaching staff) at school. Educators as multi-targeted victims at school are targets of children/adolescent and adult bullying, and this makes problem more complicated than workplace bullying in school settings. Educator-targeted workplace bullying (e.g. Jacobs & de Wet, 2018) involves bullying among adults in the school context has therefore explored educators being bullied by their principals, colleagues and/or parents of learners in hierarchical and/or horizontal relations. Bullying, whether carried out in a school environment by learner on learner, by learner to educator or by educator to educator is in nowadays world-widely researched phenomenon (e.g. De Wet & Jacobs, 2018; Woudstra, Janse Van Rensburg, Visser, & Jordaan, 2018) which has increased during last years (Kõiv, 2015).

The widely agreed definitions of bullying in the academic literature are not necessarily shared and suit to the complex school setting from the perspectives of pupils, teachers, parents and others (Smith & Monks, 2008). Adolescent learners unlikely include any of the three key characteristics of researchers’ definition into their definitions of school bullying showing tendencies to link bullying with purely physical aggressive behaviour and negative effects on victim based on self-reported questionnaire methodology (Arora & Thompson, 1987; Boulton, Trueman, & Flemington, 2002; Hellström, Persson, & Hagquist, 2015; Smith et al., 2002); free-response methodology (Byrne, Dooley, Fitzgerald, & Dolphin, 2016; Frisén, Holmqvist, & Oscarsson, 2008; Smith, Madsen, & Moody, 1999; Vaillancourt et al., 2008); and qualitative methodology (Guerin & Hennessy, 2002; Oliver & Candappa, 2003) research. A qualitative study using a focus group method found that adolescents differentiate between bullying and general interpersonal violence and aggression terms describing bullying as purposeful and repetitive (Hopkins, Taylor, Bowen, & Wood, 2013).

Adolescents’ descriptions of school bullying generally differ from teachers’ descriptions, which tend to be more in line with researchers’ definitions based on questionnaire (Boulton, 1997; Menesini, Fonzi, & Smith, 2002; Naylor et al., 2006) methodology, whereby qualitative studies (Siann, Callaghan, Lockhart, & Rawson, 1993; Mishna, Scarcello, Pepler, & Wiener, 2005) express that not all teachers have included repetition of incidents to the definitions of school bullying.

Educators’ (teachers and other school staff members) definitions of learner-on-learner bullying based on free-response methodology (Cheng, Chen, Ho, & Cheng, 2011) and qualitative methodology (De Wet & Jacobs, 2013; Harger, 2016; Lee, 2006) indicated familiarity with the definition of bullying used by researchers with some suggestions emerged from qualitative research that school bullying is an individual rather than a societal problem and solutions of this problem are within the bullies and the victims (De Wet & Jacobs, 2013).

Also, research with group of adults consisting parents and teachers suggested that most of them have more precise definition of school bullying than students, often in the line with researcher definitions (free-response methodology: Madsen, 1996; qualitative methodology: Mishna, Pepler, & Wiener, 2006; Shea et al., 2016). Within this group of adults there have evoked partially different views on peer bullying: verbal aggression (e.g. saying mean things about others) was more often an indicator of bullying for parents than for teachers (Cameron & Kovac, 2016); and teachers perceived bullying mainly as physical and verbal attacks and parents as peer rejection by the bullied child (Salehi, Patel, Taghavi, & Pooravari, 2016).

Learners’ and their parents’ definitions of school bullying are in some aspects similar in structure – both groups distinguished physical and non-physical aggressive acts and included an imbalance of power and repetition in their definition (Monks & Smith, 2006) with more emphasis to the harmful intention of the perpetrator than the victim’s harmful intention assessing as a part of the two-characteristic (repetition, power differential) bullying behavior (Thomas, Connor, Baguley, & Scott, 2017). When Smorti, Menesini, and Smith (2003) compared parents’ conceptualization of learner-on-learner bullying in five countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, England and Japan) using questionnaire recognition methodology, they found variations in the definition of bullying across terms and countries. Also, the systematic review of qualitative research (Harcourt, Jasperse, & Green, 2014) reveal variation in parents’ definitions of school bullying pointing out difficulties to define and identify bullying. For example, parents of victimized children of schoolbullying defined bullying in a way that was consistent with the literature but tended not to mention the repetitive nature of bullying behavior (Sawyer, Mishna, Pepler, & Wiener, 2011).

Non-teaching staff members’ definitions of school bullying often differ from the definitions commonly used by researchers (Hazler, Miller, Carney, & Green, 2001); likewise, non-teaching staff’ and students’ definitions also tended to differ (Eriksen, 2018; Maunder, Harrop, & Tattersall. 2010). Namely, Hazler et al. (2001) analyzed school staff members’ (teachers and counsellors) ability to differentiate bullying from other forms of aggression. Findings indicated that both professionals were more likely to rate physical acts as bullying, regardless of whether the actions fit the definition of bullying, whereby rating for these acts were more serious than to verbal or social/emotional bullying behavior. Maunder et al. (2010) compared quantitatively perceptions of bullying behaviors between pupils, teachers and support staff (e.g. lunchtime supervisors, teaching assistants). Results showed that adolescents’ and adults’ descriptions of school bullying were consistent in terms of defining indirect behaviors more likely than direct behaviors, however both adult samples defined the direct and indirect behaviors as bullying more frequently than pupils and perceived bullying behaviors as more serious than pupils. Eriksen (2018) conducted interviews among group of students and school staff (teachers, principals and school support staff) members by asking to define school bullying. Results reveal that school staff construed a rigid definition reflecting the power to decide how to follow their intervention practice and students used the term as a tool for social positioning. Also, policy-makers were interviewed about the definitions of school bullying and cyberbullying that they have used in their state policy frameworks. Most of the participants’ definitions of bullying and cyberbullying in school context did not correspond fully with the commonly agreed definition used by researchers showing partial definition for bullying and/or cyberbullying in the area of repetition and intention without mentions of power imbalance (Chalmers et al., 2016).

Problem Statement

Within the school context, this must also take account of the different types of bullying from the perspectives of teaching and non-teaching staff in the light of their conceptual understandings of educator-targeted and workplace bullying, whereby previous beforementioned studies have included bullying among learners. A limited amount of previous research, in authors' knowledge, has directed to study adults’ conceptions of workplace bullying and educator-targeted bullying.

Escartín, Zapf, Arrieta and Rodríguez-Carballeira’s (2011) cross-cultural study of employees nested in work of different organizations identified similarities in how workplace bullying is defined by large group of employees in Central America and Southern Europe – both samples of adults defined workplace bullying mainly as an hierarchical phenomenon, where the aggression took the forms of direct strategies. In another effort to define the phenomenon of workplace bullying, Saunders, Huynh and Goodman-Delahunty (2007) also collected data by using free-response methodology cross-culturally. Definitions of workplace bullying composed by adults from diverse personal and professional backgrounds reflected components used by researchers with stronger support to harmful and negative workplace behaviors and relatively less to power imbalance, intentionality and persistence of behavior. Salin’s et al., (2019) qualitative cross-cultural analyze revealed similarities in conceptualizations of workplace bullying among human resource professionals – repetition, negative effects on the target and intention to harm were typically used to decide if a behavior was bullying or not. Additional analysis of the results indicated that adults across the different countries largely saw personal harassment and physical violence as workplace bullying, whereby work-related negative acts, and social exclusion were construed very differently in the different countries.

Educators’ (teachers and principals) and social media commenters’ understandings of learner-on-educator bullying was the focus of two (De Wet, 2010, 2019) qualitative studies validating researcher’s definition about educator-targeted bullying as existing problem which was characterized by intention to do harm and repetitiveness in educators’ unequal relations with learners as aggressors. Also, the results showed that educators perceive distinguishing line between learner’s misbehavior and educator-targeted bullying (De Wet, 2010). Open-questionnaire format data of qualitative analysis gives some insight into educators’ (teacher and principal) understandings of educator-targeted workplace bullying in the area of relational powerless of victims of workplace bullying in school context as public, privately humiliated, disrespected, socially isolated and discriminated (De Wet, 2014).

Although previous researchers have examined students’, educators’, parents’ or non-teaching staff members’ conceptions of school bullying and educators’ conceptual understanding of educator-targeted bullying, no study has specifically examined social pedagogues’ views on the definition of bullying.

Research Questions

This study sought to understand social pedagogues’ perspectives of bullying in the school setting. The study was guided by the following general research question: What is social pedagogues’ understanding of bullying as multilevel concept?

The present research focus is on the conceptual understanding of three types of bullying – learner-on-learner (school bullying), learner-on-educator (educator-targeted bullying), and educator-on-adult (educator-targeted workplace bullying) bullying in school context.

Specifically, current research question was evoked: How social pedagogues, as one group of non-teaching staff members at school, differentiate their understanding of school bullying from their understanding of educator-targeted bullying and educator-targeted workplace bullying – two terms which are used interchangeably across the bullying research literature to refer victimization of educators in educator-learner relationship and in educator-adult relationship in school context.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this study was to examine social pedagogues' definitions of learner-on-learner, learner-on-educator and educator-on-adult bullying in school context.

Research Methods

Study design

This study followed an exploratory and descriptive research design to gain new insights into multilevel bullying phenomena: school bullying, educator-targeted bullying and educator-targeted workplace bullying (henceforth: workplace bullying) using a free-response methodology. To obtain a detailed description of the content structure how social pedagogues definite bullying in three relationships levels in school context, a quantitative content analysis as data analyse method was used.

Participants and data collection

A representative, voluntary sample of social pedagogues was selected. Personal e-questionnaires were sent to all social pedagogues working in Estonia at different institutions (89% at schools). The majority of the social pedagogues who were invited to take part in the study (165 of 247) completed the self-reported questionnaire. Sample of 165 social pedagogues consists of 144 females (87.3%) and 21 (12.7%) males; 24-60 years old (M = 43.31; SD = 11.06); mean overall pedagogical work experience was 14.08 years (SD = 10.91); and mean social pedagogical work experience was 7.73 years (SD = 5.59).

Data collection instrument

Data on the meaning of bullying behavior was collected by means of questionnaires in which open-ended questions were asked. The open-ended nature of this question was chosen because it placed no limitation on respondents’ identification of the number, types and nature of bullying behavior. Furthermore, in no other part of the questionnaire was any information provided that might influence respondents’ answers to this question. The participants were asked to give anonymous answers and informed that all of the data will be kept confidential. Respondents were required to answer three open-ended questions:

“What is bullying among students at school in your opinion? You can use examples, for instance.’’

“What is educator (teachers, administrative staff, parents, other staff members) targeted bullying by learners at school in your opinion? You can use examples, for instance.’’

“What is educator (teachers, administrative staff, parents, other staff members) targeted bullying by other adults at school in your opinion? You can use examples, for instance.’’

The questionnaire profile includes also background questions to determine the characteristics of the respondents.

Data analysis

The data on which this research is based are drawn from social pedagogues' answers to three open-ended questions with applying quantitative content analysis to reduce, condense, group the content, and calculate frequency of mentions comparing quantitatively the structure of responses of three open-ended questions. Quantitative content analysis was chosen to schematically and objectively describe, classify and count the numerous responses of respondents about conceptualization of bullying.

A content analysis was conducted on the answers to the open-ended questions, whereby the responses for each open-ended question were analyzed as a separate set. First, responses to the items were transcribed. Next, two independent coders (authors) segmented transcribed responses into coding units representing a total thought that stands on its own as a single word, clause or a complete sentence. Data were coded using codes generated from the data itself. These segmenting procedures were found to be highly reliable (96% inter-rater agreement of researchers), with disagreements settled with a third independent rater. Next, commonly recurring coding units were grouped as mutually exclusive subcategories and then, the subcategories were merged into categories by the same two independent raters. Lastly, the frequencies of code in (sub)categories and the frequency of the (sub)categories were calculated separately for each three open-ended questions. A series of pairwise chi-square tests were conducted to examine the association between the coding frame from a data-driven perspective.

Findings

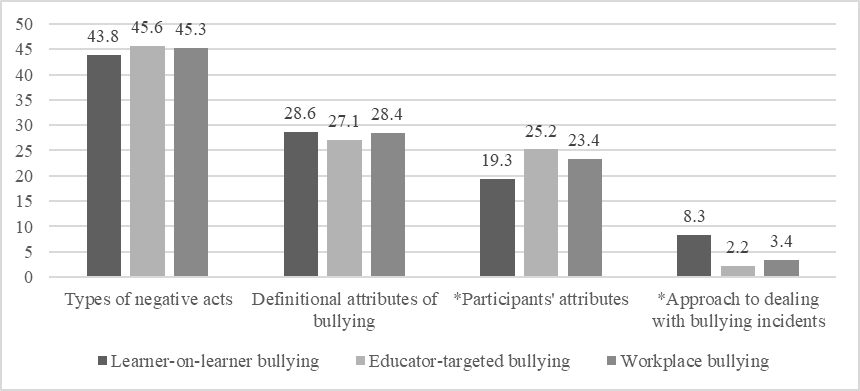

Four categories with 11 subcategories emerged from the data of quantitative content analysis: types of negative acts, definitional attributes of bullying, participants’ attributes, and approaches to dealing with bullying incidents. The most repeated coding units from the participants’ point of view settled in across these four categories were as follows: 912 cases for school bullying definitions, 798 cases for educator-targeted bullying, and 769 cases for workplace bullying in school context. In total, 2479 coding units were extracted. Table

Research results revealed that respondents’ definitions of bullying reflected specific behavioral features suggested in researchers’ definition as categories of content analysis – types of negative acts, definitional attributes of bullying, and specific behavioral features – participants’ attributes, approach to dealing with bullying incidents, across all three types of bullying (Figure

Several statistically significant differences measured by using pairwise χ2 tests between frequencies of variables identified in quantitative content analysis were revealed in the level of p < 0.001 as a function of type of bullying (Table

Within the types of negative acts category, participants referred to verbal bullying (offensive remarks, name-calling, humiliating, shouting, ridiculing), indirect bullying (social isolation, social rejection, slandering, withholding of information, cyberbullying), physical bullying (serious overt acts of violence, damage or theft of personal property, threatening with violence) and work-related bullying (harm to personal position and destabilization). The verbal component with specific serious direct aggression forms – offensive remarks and insults, was dominant characteristic across all three types of bullying definitions, whereby name-calling as personal harm was more prevalent in conceptions of school bullying; and humiliating and ridiculing as harm to professional standing was more prevalent in conceptions of educator-targeted bullying and workplace bullying. Indirect bullying was included in the learner-on-educator descriptions of bullying less frequently compared with learner-on-learner and educator-on-adult bullying descriptions with overwhelming form of bullying – social isolation and ignoring. The prevalent forms in descriptions of workplace bullying were slandering and withholding of information, and in descriptions of school bullying social rejection and social exclusion. Work-related forms of negative acts as destabilization of work (favouritism, removal of responsibility, unreasonable workload) were more frequent in definitions describing workplace bullying; and public harm to personal position (violence of formal rules and orders, arguing and contradiction, publication of personal info) was more significant in conceptual understanding of educator-targeted bullying. The last common category included in the definitions of three types of bullying by respondents was physical bullying (e.g. damage or theft of personal property, threatening with violence), whereby direct serious physical bullying acts (hitting, kicking, pushing) had significantly more likely included into learner-on-learner bullying definitions than learner-on-educator and educator-on-adult bullying definitions.

Within the definitional attributes of bullying category, definitions across the three types of bullying reflected attributes of bullying (intent, harm or hurt, repeated, power imbalance, difficult for the victim to defend him- or herself) and non-specific attributes of bullying (bullying-related terms, behaviors not defined as bullying). Although, participants’ definitions of three types of bullying were encapsulated by four general sub-themes generally adopted in research literature (intent, harm or hurt, repeated, power imbalance), whereby there were differences between conceptualization of school bullying and other two types of bullying by including more frequently the sub-themes connected with difficulties for the victim to defend him/herself into the descriptions of school bullying. Additionally, results indicated that conceptions of three types of bullying included several bullying-related terms (abuse, provocation, harassment, manipulation) and distinguishing features of bullying from other forms of unfavorable behaviors like single incident of aggression, conflict, teasing or fights between equals. Within the participants’ attributes category, definitions across the three types of bullying reflected number of participants (group-based bullying and individual-based bullying), participants roles (bystanders, adults as victims and perpetrators of bullying), and participants’ physical and personality characteristics. School bullying and workplace bullying was conceptualized by social pedagogues mainly in terms of one-to-one aggression in contrast to conceptualizations of bullying of educators by group of students. With regard to the participants’ roles subcategory participants considered workplace bullying a phenomenon perpetrated by adults (co-workers, principals, parents) in hierarchical relations; and educator-targeted bullying as a phenomenon victimized by adults (teachers and other staff members), whereby school bullying was conceptualized in more large social contexts involving also bystanders. In addition, the personality characteristics of bullies (as low self-esteem, lack of empathy, poor self-regulation) were used more often to define workplace bullying in contrast to describe more personality characteristics of victims (as poor social skills, lack of assertiveness and self-regulation) to define educator-targeted bullying. Also, results showed that physical characteristic of bullies and victims reflected physical power imbalance and were more emphasized components in school bullying definitions compared with other types bullying definitions.

Finally, within the approach to dealing with bullying incidents, participants referred to handling bullying incidents (working with victim using problem-solving approach and working with bully using rule-sanctions approach) and whole-school strategies for prevention and intervention of bullying. Differences were found regarding the definition the participants used for school bullying compared with both other forms of educator-targeted bullying: Participants included more descriptions of handling with bullying incidents (working with bullies and victims) and whole-school prevention and intervention approaches into their descriptions of school bullying definitions.

Conclusion

There is currently a wide variety of professionals who work with learners within the school community, ranging from educators to non-teaching personnel, included also different members of school supporting staff (e.g. counsellors, psychologists, social workers, social pedagogues). Previous prevalence studies indicated that the educator-targeted (Billett, Fogelgarn, & Burns, 2019; Uz, & Bayraktar, 2019; Woudstra et al., 2018) and educator-targeted workplace (De Wet, 2014; Kõiv, 2015) bullying is problem for educators, but also for non-teaching staff members (McGuckin & Lewis, 2008), social workers (Whitaker, 2012) and social pedagogues (Kõiv, 2017) with social pedagogic perspective on dealing bullying in schools (Kyriacou, Mylonakou-Keke, & Stephens, 2016).

As previous literature had already shown that pupils’, educators’ and non-teaching staff members’ definitions of school bullying are not straightforward, and more attention needs to be given to non-teaching staff members’ – especially support staff members’, interpretations of bullying as multilevel concept. How educators and non-teaching staff members define bullying is not a trivial issue – they are key roles of adults in schools to recognize and responding to bullying incidents. People’s definitions of what constitutes bullying are critical in an assessment of people’s responses to bullying behavior (e.g. Ellis & Shute, 2007; Vaillancourt et al., 2008) and can shape how they respond to bullying in everyday life (Madsen, 1996) having, for example, difficulties to distinguishing bullying from other forms of interaction (Hazler et al., 2001).

This is one of the first studies that has tried to analyze how social pedagogues’ definitions of bullying can vary across three types of bullying, reflecting not only the differences but also the existing similarities. Hence, these results highlight the nature the multilevel bullying phenomenon per se, which have some ‘‘core aspects’’ of school bullying (learner-on-learner), educator-targeted (learner-on-educator) and educator-targeted workplace (educator-on-adult) bullying.

At first, the results showed that social pedagogues emphasized combination of components (different types of aggression, intention to cause harm, repetition, and a power imbalance), which differentiate bullying from other forms of aggressive behaviour across three types of bullying conceptions. Previous studies among teachers (Menesini et al., 2002), teachers and counsellors (Hazler et al., 2001) and parents (Smorti et al., 2003) show that these groups of adults can differentiate between school bullying and other forms of aggression.

While researchers’ definitions of bullying typically emphasize power imbalance, repetition, and

intention to cause harm in their definitions, these concepts were identified in the present study as social pedagogues’ definitions across three types of bullying with recognition of several forms of aggressive behavior, which differentiate three types of bullying from each other. Namely, present analysis revealing that: (1) all three types of bullying were described by social pedagogues as repeated, intended aggressive behaviors with power imbalance, whereby the difficulties of victims to defend themselves were more empathized in school bullying compared with conceptualization of educator-targeted bullying types; (2) a variety of negative aggressive acts (verbal, indirect, physical) were highly characteristic across all three concepts of bullying with more emphasis to serious physical acts in the concept of school bullying; relatively less attention to indirect acts and more emphasis to direct personal verbal acts in the concepts of educator-targeted bullying; more stresses to work-related negative acts as indicators of harm to professional standing in the conceptualization of educator-targeted bullying; and more attention to destabilization of work as dominant form in the concept of educator-targeted workplace bullying.

Thus, the present research findings support the idea that there are similarities between social pedagogues’ and researchers’ definitions of bullying showing that the participants held a shared understanding of three definitions of bullying in the area of intentionality, repetitiveness and inequality of power, whereby different aggression types (indirect, physical, verbal, work-related) differentiated three types of bullying – school bullying, educator-targeted bullying and educator-targeted workplace bullying.

Most adult respondents (parents: Monks & Smith, 2006; Sawyer et al., 2011; Smorti et al., 2003; teachers and parents: Madsen, 1996; Mishna et al., 2006; teachers and staff members: Harger, 2016; Cheng et al., 2011; teachers: Menesini et al., 2002; Mishna et al., 2005; Naylor et al., 2006; Siann et al., 1993) incorporated into their understanding of learner-on-learner bullying the key components of the generally accepted bullying definition, whereby the same tendencies were revealed among adults in the area of defining workplace bullying (Salin et al., 2019; Saunders et al., 2007) and among educators (De Wet, 2010; 2019) in the area of teacher-targeted bullying conceptualizations. Also, present results among social pedagogues confirmed the tendency for teachers, parents, school staff members to focus on physical and verbal behaviours when they describe learner-on-learner bullying (e.g. Boulton, 1997; de Wet & Jacobs, 2013; Harger, 2016; Hazler, et al., 2001; Maunder et al, 2010; Monks & Smith, 2006; Naylor et al., 2006; Salehi et al., 2016; Sawyer et al., 2011; Siann et al., 1993).

Secondly, social pedagogues in this study operated broader multilevel bullying definitions as found in the literature with significance of intervention and prevention of bullying and attention to the characteristics of individuals engaging in the bullying behavior, whereby these two additional characteristics differentiate conceptions of three type of bullying from each other. Specifically, four distinguishing aspects of three types of definitions of bullying from the perspective of the social pedagogues were revealed: (1) type of aggression: physical aggression vs. verbal professional work-related aggression distinguish school bullying from educator-targeted bullying by students and by adults; (2) power relationship character: horizontal physical power imbalance between bully and victim with attendance of bystanders vs. hierarchical psychological or social power imbalance between bullies and victims distinguish school bullying from educator-targeted bullying by students and by adults; (3) manifestations of workplace bullying forms: harm to personal position in work context vs. work destabilization distinguish bullying of educators by students from bullying of educators by adults; (4) characteristics of individuals engaged in bullying: indirect personal on-to-one aggression in the form of social exclusion vs. verbal direct group-based aggression distinguish educator-targeted bullying by adults and school bullying from bullying of educators by students.

Thus, the present study clearly demonstrated that pedagogues’ multilevel concept of bullying share researchers views about what behaviors should be classed as bullying with broader conception of bullying behavior laying out as individual as well as group-based phenomenon which contribute to the intervention-prevention practice in schools.

From a practical point of view, the fact that the social pedagogues’ understanding of three types of bullying does not differ substantially from academic definitions with adding components connected with recognizing individuals engaging in bullying and approaches dealing with bullying, has some connections with previous works reflecting positive implications for the development of strategies for dealing effectively with this multilevel phenomenon at school context.

Social pedagogues’ definitions of school bullying, educator-targeted bullying and educator-targeted workplace bullying presented intervention and prevention from the school staff being in the line of previous studies among teachers and support staff members (Eriksen, 2018) who accentuated the intervention component in their conceptions of school bullying with need to teach students the established definition of bullying. Also, teachers have perceived educators’ important role in school-bullying prevention and intervention with need for prevention training in this area (Kennedy, Russom, & Kevorkian, 2012). Anti-bullying policies should protect all learners, educators and non-teaching staff members against learner targeted and staff targeted bullying in schools. Such policies should be established in order to combat bullying incidents that affect learners, educators and non-teaching staff members with starting of overwhelming discussions about all forms of bullying from every school community members’ perspective and following support staff members leading roles in this process.

Differences between three types of conceptual understanding of bullying behavior among social pedagogues mainly follow previous studies in the area of conceptualizing workplace bullying among adults (Escartín et al., 2011; De Wet, 2014; Salin, et al., 2019), showing that bullying against educators by students and by adults was mainly conceptualized as a hierarchical phenomenon, where the aggression took the form of direct professional work-related strategies, whereby the main differentiating features for this two concepts were the manifestations of workplace bullying forms (public personal or destabilization) and bullying social context (individual or group-based).

The findings address an important gap as they highlight the multilevel conceptualization of bullying and the need to expand the bullying literature in this area to capture the perspectives of one professional – social pedagogues.

In terms of strengths, this study used a large, nationally representative dataset in Estonia to

examine social pedagogues’ definitions of bullying. This study adds value to the field, in the sense that it offers a set of results that will stimulate research on the professional similarities and differences of defining bullying among support staff members at school. The findings of this study have implications for future research to have a better understanding in order to assess the information from multiple support staff respondents to gaining insights into different perspectives of definitions of bullying.

The study was limited to conceptualizations of bullying such as learner-on-learner bullying, learner-on-educator, and educator-on-adults bullying and future research should focus also to educator-on-learner bullying, educator-on-educator bullying, educator-on-principal, educator-on-nonteaching staff and educator-on-parents bullying conceptions.

References

- Arora, T., & Thompson, D. (1987) Defining bullying for a secondary school. Education and Child Psychology, 4, 110–120.

- Billett, P., Fogelgarn, R., & Burns, E. (2019). Teacher targeted bullying and harassment by students and parents: Report from an Australian exploratory study. Australia: Latrobe University.

- Boulton, M. J. (1997). Teachers’ views on bullying: Definitions, attitudes and ability to cope. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 223–233.

- Boulton, M. J., Trueman, M., & Flemington, I. (2002). Associations between secondary school pupils' definitions of bullying, attitudes towards bullying, and tendencies to engage in bullying: Age and sex differences. Educational Studies, 28(4), 353–370.

- Byrne, H., Dooley, B., Fitzgerald, A., & Dolphin, L. (2016). Adolescents’ definitions of bullying: the contribution of age, gender, and experience of bullying. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(3), 403–418.

- Cameron, D. L., & Kovac, V. B. (2016) An examination of parents’ and preschool workers’ perspectives on bullying in preschool. Early Child Development and Care, 186(12), 1961–1971

- Chalmers, C., Campbell, M. A., Spears, B. A., Butler, D., Cross, D., Slee, P., & Kift, S. (2016). School policies on bullying and cyberbullying: Perspectives across three Australian states. Educational Research, 58(1), 91–109.

- Cheng, Y. Y., Chen, L. M., Ho, H. C., & Cheng, C. L. (2011). Definitions of school bullying in Taiwan: a comparison of multiple perspectives. School Psychology International, 32(3), 227–243.

- De Wet, C. (2010). Victims of educator-targeted bullying: A qualitative study. South African Journal of Education, 30(2), 189–201.

- De Wet, C. (2014). Educators’ understanding of workplace bullying. South African Journal of Education, 34(1), 1–16.

- De Wet, C. (2019). Understanding teacher-targeted bullying: Commenters’ views. Glocal Education in Practice: Teaching, Researching, and Citizenship BCES Conference Books, 2019, Volume 17 (pp. 94–100). Sofia: Bulgarian Comparative Education Society.

- De Wet, C., & Jacobs, L. (2013). South African teachers’ exposure to workplace bullying. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 9(3), 446–464.

- De Wet, C., & Jacobs, L. (2018). Workplace bullying, emotional abuse and harassment in schools. In P. D’Cruz, E. Noronha, L. Keashly, & S. Tye-Williams S. (Eds.), Special topics and particular occupations, professions and sectors. Handbooks of workplace bullying, emotional abuse and harassment, Vol. 4 (pp. 1–34). Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Ellis, A. A., & Shute, R. (2007). Teacher responses to bullying in relation to moral orientation and seriousness of bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 649–663.

- Eriksen, I. M. (2018). The power of the word: Students’ and school staff’s use of the established bullying definition. Educational Research, 60(2), 157–170.

- Escartín, J., Zapf, D., Arrieta, C., & Rodríguez-Carballeira, Á. (2011). Workers' perception of workplace bullying: A cross-cultural study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(2), 178–205.

- Farrington, D. (1993). Understanding and preventing bullying. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and Justice: A review of research, Vol. 17 (pp. 381–458). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Frisén, A., Holmqvist, K., & Oscarsson, D. (2008). 13 year-olds’ perception of bullying: Definitions, reasons for victimisation and experience of adults’ response. Educational Studies, 34(2), 105–117.

- Guerin, S., & Hennessy, E. (2002). Pupils’ definitions of bullying. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 17(3), 249–261.

- Harcourt, S., Jasperse, M., & Green, V. A. (2014). ‘‘We were sad and we were angry’’: A systematic review of parents’ perspectives on bullying. Child Youth Care Forum, 43, 373–391.

- Harger, B. (2016). You say bully, I say bullied: School culture and definitions of bullying in two elementary schools. In Y. Besen-Cassino, & L. E. Bass (Eds.), Education and youth today (Sociological Studies of Children and Youth, Vol. 20) (pp. 93–121). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hazler, R. J., Miller, D. L., Carney, J. V., & Green, S. (2001). Adult recognition of school bullying situations. Educational Research, 43, 133–146.

- Hellström, L., Persson, L., & Hagquist, C. (2015). Understanding and defining bullying – adolescents’ own views. Archives of Public Health, 73(4), 1–9.

- Hopkins, L., Taylor, L., Bowen, E., & Wood, C. (2013). A qualitative study investigating adolescents' understanding of aggression, bullying and violence. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 685–693.

- Jacobs, L., & de Wet, C. (2018). The complexity of teacher-targeted workplace bullying: An analysis for policy. Journal for Juridical Science, 43(2), 53–78.

- Kennedy, T. D., Russom, A. G., & Kevorkian, M. M. (2012). Teacher and administrator perceptions of bullying in schools. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 7(5), 1–11.

- Kõiv, K. (2015): Changes over a ten-year interval in the prevalence of teacher targeted bullying. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 171, 126–133.

- Kõiv, K. (2017). Õpetaja ja sotsiaalpedagoog kui kiusamise ohvrid/Teachers and social pedagogues as victims of bullying. Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri. Estonian Journal of Education, 5(2), 133–154.

- Kyriacou, C., Mylonakou-Keke, I., & Stephens, P. (2016). Social pedagogy and bullying in schools: The views of university students in England, Greece and Norway. British Educational Research Journal, 42(4), 631–645.

- Lee, C. (2006). Exploring teachers' definitions of bullying. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 11(1), 61–75.

- Madsen, K. C. (1996). Differing perceptions of bullying and their practical implications. Education and Child Psychology, 13(2), 14–22.

- Maunder, R. E., Harrop, A., & Tattersall, A. J. (2010). Pupil and staff perceptions of bullying in secondary schools: Comparing behavioural definitions and their perceived seriousness. Educational Research, 52(3), 263–282.

- McGuckin, C., & Lewis, C. A. (2008). Management of bullying in Northern Ireland schools: A pre-legislative survey. Educational Research, 50(1), 9–23.

- Menesini, E., Fonzi, A., & Smith, P. K. (2002). Attribution of meanings to terms related to bullying: A comparison between teacher’s and pupil’s perspectives in Italy. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 17(4), 393–406.

- Mishna, F., Scarcello, I., Pepler, D., & Wiener, J. D. (2005). Teachers’ understanding of bullying. Canadian Journal of Education, 28(4), 718–738.

- Mishna, F., Pepler, D., & Wiener, J. (2006). Factors associated with perceptions and responses to bullying situations by children, parents, teachers, and principals. Victims and Offenders: An International Journal of Evidence-based Research, Policy, and Practice, 1, 255–288.

- Monks, C., & Coyne, I. (Eds.) (2011). Bullying in different contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Monks, C. P., & Smith, P. K. (2006). Definitions of bullying: age differences in understanding of the term, and the role of experience. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24, 801–821.

- Naylor, P., Cowie, H., Cossin, F., de Bettencourt, R., & Lemme, F. (2006). Teachers’ and pupils’ definitions of bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 553–76.

- Oliver, C., & Candappa, M. (2003). Tackling bullying: Listening to the views of children and young people. DfES Research Report No. 400. London: Department for Education and Skills.

- Olweus, D. (1999). Norway. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: a cross-national perspective (pp. 28–48). London: Routledge.

- Salehi, S., Patel, A., Taghavi, M., & Pooravari, M. (2016). Primary school teachers and parents perception of peer bullying among children in Iran: A qualitative study. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 10(3), 1–8.

- Salin, D., Cowan, R., Adewumi, O., Apospori, E., Bochantin, J., D’Cruz, P.,..Zedlacher, E. (2019). Workplace bullying across the globe: A cross-cultural comparison. Personnel Review, 48(1), 204–221

- Saunders, P., Huynh, A., & Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2007). Defining workplace bullying behaviour professional lay definitions of workplace bullying. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 30, 340–354.

- Sawyer, J.-L., Mishna, F., Pepler, D., & Wiener, J. (2011). The missing voice: Parents’ perspectives of bullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 1795–1803.

- Shea, M., Wang, C., Shi, W., Gonzalez, V., & Espelage, D. (2016). Parents and teachers’ perspectives on school bullying among elementary school-aged Asian and Latino immigrant children. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 7(2), 83–96.

- Siann, G., Callaghan, M., Lockhart, R., & Rawson, L. (1993). Bullying: Teachers’ views and school effects. Educational Studies, 19, 307–321.

- Smith, P. K., Madsen, K. C., & Moody, J. C. (1999). What causes the age decline in reports of being bullied at school? Towards a developmental analysis of risks of being bullied. Educational Research, 41(3), 267–285.

- Smith, P. K., & Monks, C. P. (2008). Concepts of bullying: Developmental and cultural aspects. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20(2), 101–112.

- Smith, P. L., Cowie, H., Olafsson, R., Liefooghe, A., Almeida, A., Araki, H.,…Wenxin, H. (2002). Definitions of bullying: A comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a fourteen-country international comparison. Child Development, 73(4), 1119–1133.

- Smorti, A., Menesini, E., & Smith, P. K. (2003). Parents’ definitions of bullying in a five-country comparison. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 43(4), 417–432.

- Thomas, H. J., Connor J. P., Baguley, C. M., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Two sides to the story: Adolescent and parent views on harmful intention in defining school bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 43(4), 352–363

- Uz, R., & Bayraktar, M. (2019). Bullying toward teachers and classroom management skills. European Journal of Educational Research, 8(2), 647–657

- Vaillancourt, T., McDougall, P., Krygsman, A., Hymel, S.,Miller, J., Stiver, K., & Davis, C. (2008). Bullying: are researchers and children/youth talking about the same thing? Journal of Behavioural Development, 32, 486–495.

- Whitaker, T. (2012). Social workers and workplace bullying: Perceptions, responses and implications. Work, 42(1), 115–123

- Woudstra, M. H., Janse Van Rensburg, E., Visser, M., & Jordaan, J. (2018). Learner-to-teacher bullying as a potential factor influencing teachers’ mental health. South African Journal of Education, 38(1), 1–10.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

07 November 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-071-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

72

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-794

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Aia-Utsal, M., & Kõiv*, K. (2019). Social Pedagogues’ Definitions Of Three Types Of Bullying. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2019: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 72. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1-15). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.11.1