Abstract

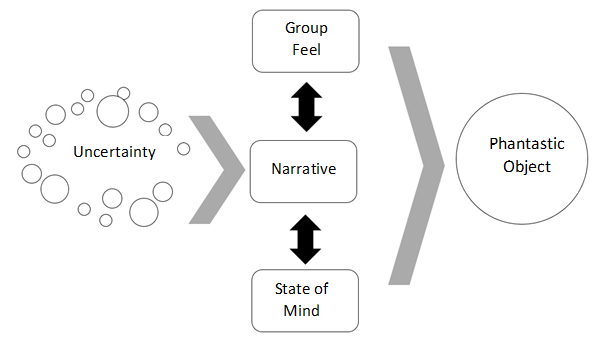

In this study, the narratives, one of the important building blocks of emotional finance, is discussed. Emotional finance examines the role of unconscious mental processes in financial decision making on the basis of psychoanalysis. It uses concepts such as narrative, group feel, states of mind and phantasy in order to explain the behavior of investors in a market dominated by uncertainty Emotional finance has increasingly been discussed especially in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. In these studies, the crisis periods and the formation of asset price bubbles, all which the conventional finance theory had difficulty in explaining, have been handled through the group feel, narratives, states of mind and phantasy concepts. Through this study, the effect of narratives over financial decision making is considered from the perspective of emotional finance. Moreover, the role of narratives in the periods of asset price bubbles and financial crisis is explained. Narratives play a critical role in enabling individuals who must make decisions under uncertainty to imagine the future and to act.

Keywords: Emotional financenarrativesasset price bubblesfinancial crisis

Introduction

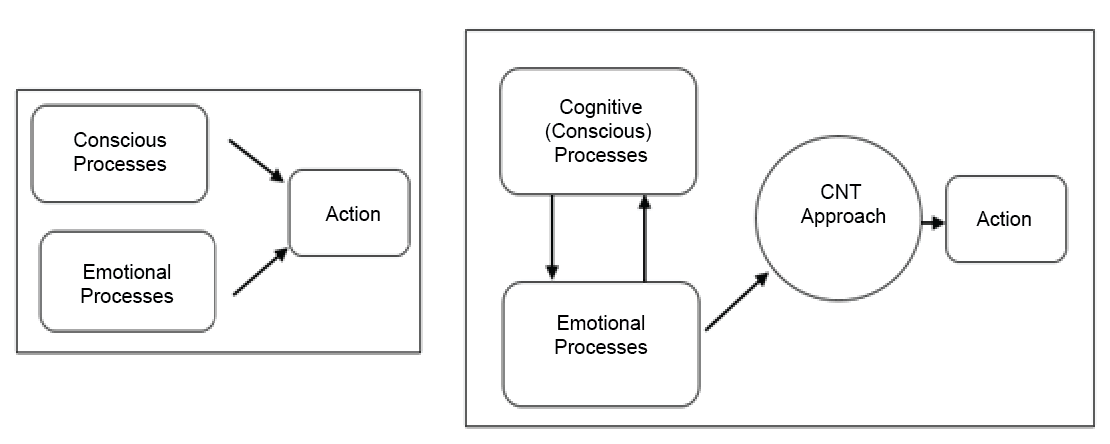

Conventional finance theories cannot help to explain why individuals invest, how they create their portfolios, why the returns are not solely identified by risk, or how asset price bubbles are occurred (O’Hara 2008, as cited in Taffler, 2017). One of the most important assumptions of finance theories that started to develop since the 1950s; economic agents exhibit rational behavior. According to this assumption; individuals decide to maximize their interests without being affected by their social environment or without taking any moral or social motives. Although this assumption underlying the theories of finance is seen as a simplified assumption, in fact the theories have serious implications for their practical implications. The market anomalies that started to be seen since the 1970s could not be explained by the prevailing theories and the need to produce new paradigms became undeniable. The theory of behavioral finance, which began to evolve in the 1980s, revealed that people are not rational as the conventional approach predicted, have various biases, and that these biases play an important role in the financial decision-making process. According to Statman (2014) people are not rational, but "normal". While conventional finance explains how people should behave, behavioral finance tries to explain how people behave. The biggest criticism of behavioral finance is that it has not been able to produce a model. It reveals the reasons for behavior, but it can't reveal a valuation model based on it. In the 2000s, studies in the field of neuro-finance began to emerge. Neuro-finance investigates the structure of the brain in the financial decision-making process and tries to reveal which regions are active or passive by which factors. It conducts researches in laboratory environment by using FMRi devices. Criticisms directed to behavioral finance also can be directed to neuro-finance. In other words, neuro finance reveals the structure and functioning of the brain in the decision-making process, but it cannot present a model like behavioral finance. The emotional finance theory, which began to develop in the 2000s and attracted considerable attention after the 2008 crisis, eliminates some of the criticisms directed to behavioral finance and neuro-finance. The approach of emotional finance; models the behavioral patterns of economic agents and thus provides a pattern for market behaviors. Emotional finance examines the role of unconscious mental processes in financial decision making on the basis of psychoanalysis. As shown in the figure

According to Taffler and Tuckett (2010), the starting point of attempting to understand investment behavior is to recognize that investment activities, as traditionally claimed, are not merely to maximize financial returns and have a much deeper meaning in unconscious reality. In our complex, dynamic and interconnected world, many important decisions are uncertain (King, 2016; Simon, 1955, as cited in Tuckett & Nikolic, 2017). According to the emotional finance approach, when uncertainty prevails, as in financial markets, individuals have to create a story to imagine this uncertainty and to support their decisions to act (Tuckett, Smith, & Nyman, 2014). Within the scope of this study, the functions of narratives, the impact of narratives on financial decision making, the role of narratives in the context of financial crises and asset price balloons will be evaluated from the perspective of emotional finance.

The Functions of Narratives, and their Impact on Financial Decision-making

According to the Turkish Language Institute (TDK), a narrative is “telling an incident verbally / in writing,” or “a genre of prose relating real or fictitious events, a story.” (http://www.tdk.gov.tr/index.php?option=com_gts&arama=gts&kelime=hik%C3%A2ye&uid=22916&guid=TDK.GTS.5be9c1ac320fe4.54203763 accessed 12.11.2018) Gabriel (2000) indicates that the story shares a common etymology with history; while creating the communal memory, the story connects the past to the future (Pellowski 1990 as cited in Engin, 2013) lists the reasons for the emergence of stories as human beings’ need to entertain themselves, an effort to explain the world in which they live, and the need to hand down their experiences. Stories are universal, and stories from different cultures share most of the same metaphors and themes. (Hogan, 2003, as cited in Johnson & Tuckett, 2017). We know that our ancestors have been telling stories for as long as history (e.g. the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh), and probably for even longer (Abbott, 2000 as cited in Johnson & Tuckett, 2017). Fisher (1984 as cited in Humphreys & Brown 2002) defined human beings as “Homo narrans,” “the story-telling animal.” Although the concepts of story and narrative are frequently used interchangeably, these two concepts are actually different from each other. All stories are narratives, but not all narratives are stories. Put simply, a story is about a character and the events befalling that character, while narrative, rather than “what is told,” is more interested in how it is told. Seen from this angle, a story may be told in different ways, that is, different narratives may emerge from a single story. In fact, narrative points to the act of expressing oneself. According to the TDK, narrative means “the form of relating a sequence of events in genres such as the novel, story, fairy tale etc.; relating.” (http://www.tdk.gov.tr/index.php?option=com_gts&arama=gts&guid=TDK.GTS.5be9c1d7859ca7.86047629 accessed 12.11.2018 ) Examining the English origin of the word, narrative has two etymological origins: “relating” (narra) and “knowing somehow” (gnarus). These two meanings are intertwined, and cannot be thought of separately (Tuckett, 2011). According to Abbot (2011, as cited in Sezen, 2011), narrative bears traces of these two words, that is, it contains the meanings of both learning or knowing a piece of information, and telling or expressing it. According to Dervişcemaloğlu (2016), while we may think of narratives as limited to literary narratives such novels and stories, they are related to the word “narrate,” and narratives are everywhere.

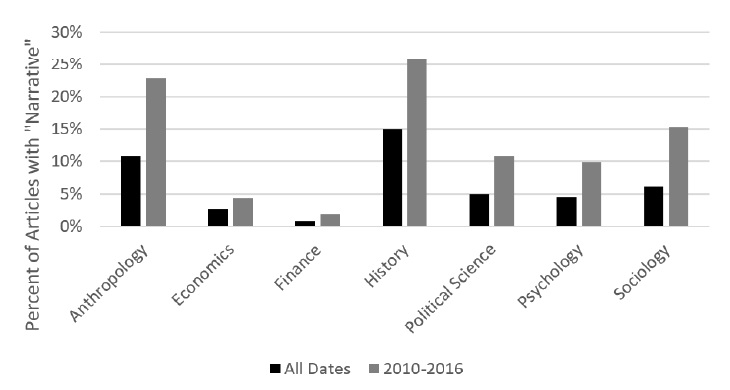

Narrative theory, or Narratology in the international recognised terminology, is the study of narrative as a genre. Its purpose is to define the characteristics, variables and combinations of narrative (Fludernik, 2009). Emerging as a sub-discipline of literature in the 1970s, Narratology found itself a place in many different fields. In the twentieth century, an increasing number of scientific disciplines, such as anthropology, psychoanalysis and history started to take an interest in narrative, and many works were produced on narratives. Dervişcemaloğlu (2016) indicates that research proves that the human brain is structured to make sense of a multitude of complex relationships through narrative, and that narratives are indispensable for all disciplines.

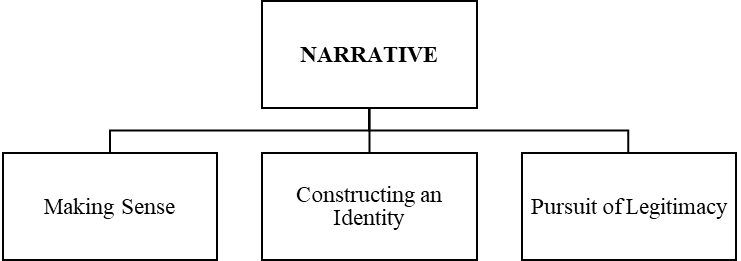

Research on narrative started as early as Aristoteles. As shown in the figure

The introduction of narrative studies to the science of business administration was with the organisational theory. Although neglected by the organisational perspective up to the 1970s, we can say that narrative found itself a place in organisational theory along with an increase in studies especially on organisational culture. According to Mitroff and Kilmann (1975), “

As seen in Figure

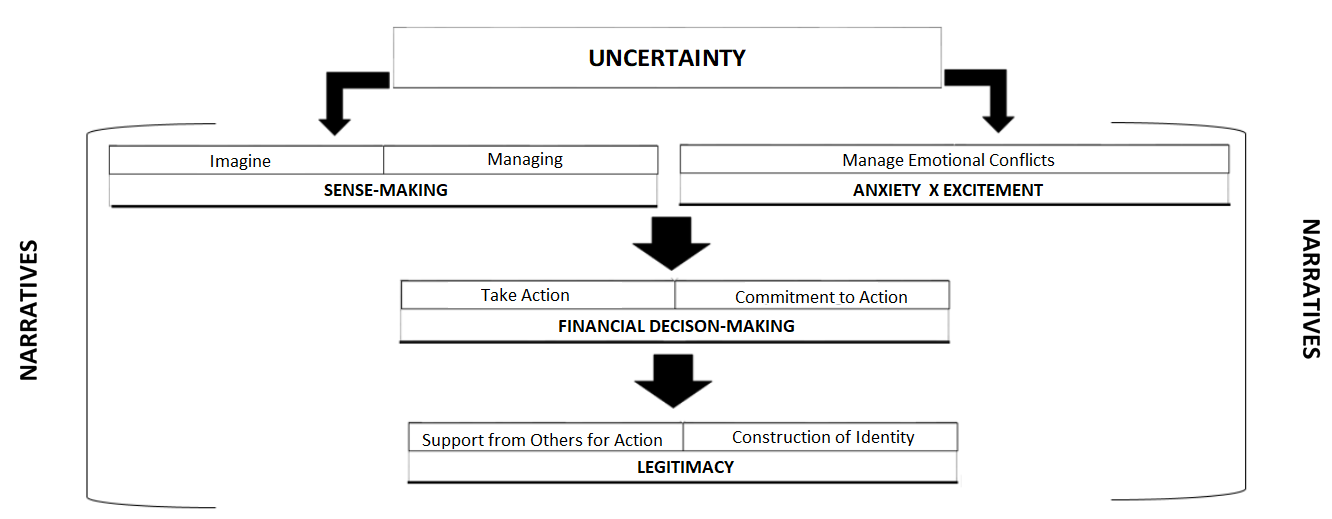

Essentially, risk and uncertainty are different concepts. According to Ricciardi (2008, as cited in Taffler, 2017), risk may be defined, measured and known based on the idea that the past may in a way be used to predict the future, and that the probability distribution of probable outcomes may be objectively or subjectively assessed. On the other hand, uncertainty cannot be defined, measured and known. According to Knight (1921), uncertainty must be kept separate from the concept of risk, from which it is never separated properly. The fundamental difference between risk and uncertainty is that, while the distribution of the outcomes of a series of events is known in the case of risk, this distribution is not known in the case of uncertainty. While the fact that the probable outcomes and the distribution of these outcomes are known renders risk measurable, uncertainty cannot be measured. According to Tuckett (2012), investors clearly face “radical” uncertainty and informational ambiguity. Tuckett and Nikolic (2017) maintained that the concept of radical uncertainty defined situations in which the outcomes of actions are ambiguous, building the problem structure in order to make a choice between alternatives is difficult, and representing the future comprehensively is impossible. Keynes considered uncertainty as a threat against reliability, and designed animal spirits as a solution for action (Chong & Tuckett, 2015). According to Tuckett (2012), Keynes, when referring to animal spirits, thought of mindsets that focused on emotions along with the intellect in order to assist the decision-making process under irrationality and uncertainty. In order to be able to act, that is, to make financial decisions, investors must imagine and manage uncertainty. In other words, they must make sense of this uncertainty. Whittle and Mueller (2012, as cited in Eshraghi & Taffler, 2015) define making sense as “the process by which humans interpret themselves and the world around them by means of generating meaning”. Narrative is a natural human process that helps humans make sense of their lives, and ultimately shapes how they live (Bruner, 1991). It enables us to construct events and the everyday meanings of these events along with their causal effects (Tuckett & Nikolic, 2017). According to Ochs and Capps (1996), narratives connect unrelated events, associate the past, the present and the imaginary future, socialise emotions and the identity, and transforms the individual into a member of society. From a finance point of view, investors make sense of the uncertainty engulfing them through narratives, and feel that an unmanageable future may be managed and controlled to a certain extent (Eshraghi & Taffler 2015). Let us consider fund managers, who are among the important actors of the markets. The decisions made by fund managers are very important as they affect the distribution of deposits across the economy. In order that they may be able continue their business, fund managers must be resolute in the face of uncertainty (Tuckett & Taffler, 2012). The stories told by fund managers about their investments, play an important role in building the trust they need to make daily decisions in a chaotic, uncertain and highly unpredictable environment (Tuckett & Taffler, 2012). Narratives charge the work carried out by a fund manager with meaning, assisting them in thinking that they can control an unpredictable world with which they must deal. On the other hand, according to Tuckett and Nikolic (2017), narratives play an important role such as prohibiting problems and negative emotions arising from uncertainty. Narratives, when they carry out these functions, allow actions to be performed. Chong and Tuckett (2015) stated that when individuals are faced with uncertain situations, the feeling of anxiety about the loss and the feeling of excitement about the gain is inevitable and the participants manage these emotional conflicts through narrative construction. Nyman (2015) indicates that individuals create narratives that form an adequate opinion regarding potential returns while repressing their anxiety and concerns against potential losses, and act thanks to this. In short, narratives, while helping to make sense of uncertainty, end the conflict between the emotions of anxiety and enthusiasm. They help individuals to act, and to maintain their commitment to the action they carry out. Another important function of narratives that is discussed in the literature is that individuals construct and legitimise an identity through narratives. According to Gendron and Spira (2010, as cited in Esraghi & Taffler, 2015), identity is important as it plays a key role in making sense. It expresses who we are, and the nature of our relationship with others and the world. When individuals tell a story about themselves, the individual’s identity takes the form of a narrative filled with scenes, characters, and events (McAdams, 2001), and this narrative answers certain questions on identity: Who am I? How did I come to this point? Where is my life going? (McAdams & McLean, 2013). Through narratives, the individual both constructs an identity, and ensures that this identity they created is acceptable to others. The individual’s creation of a narrative about themselves is an important tool for ensuring that others recognise and approve this claim to identity. Research conducted indicates that humans, while desiring to see themselves in certain way, do not feel this identity fully until they achieve a state of social reality by being recognised by other humans (Baumeister & Newman, 1994). This brings us to the concept of the pursuit of legitimacy. Suchman (1995, as cited in Esraghi & Taffler, 2015) defines legitimacy as “the general perception or assumption that the actions of a being are desirable, proper or decent within a system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions that is created socially”. In studies conducted on fund managers in the literature of emotional finance (Tuckett & Taffler, 2012; Esraghi & Taffler, 2015), it was shown that these people resort to narratives in order to legitimise the investment decisions they make. On the other hand, it is seen that fund managers create narratives that depict themselves as “heroes” when their investments succeed, but as “victims” when these fail. According to emotional finance, individuals use narratives both to legitimise the decisions they make, and to create an identity for themselves. Another aspect of the pursuit of legitimacy and the creation of identity is that individuals receive support from others in the social context in which they exist. According to Tuckket and Nikolic (2017), narratives help individuals to receive support from others for the actions they choose. Figure

In the theory of emotional finance, the role of narratives has been studied in depth in some studies. The Conviction Narrative Theory (CNT), which attempts to explain how individuals make decisions under uncertainty through narratives, and how they commit to these decisions, was born within the framework of these studies. According to Nyman (2015), the socio-psychological decision-making theory known as the Conviction Narrative Theory (CNT) aims at understanding and explaining how individuals make decisions in cases where “optimal” choices cannot be made. Conviction means “belief,” and also “being sentenced.” According to this theory, individuals have a strong belief for narratives; in other words, they become captives of these narratives. Tuckett and Nikolic (2017) suggest that Conviction Narratives help decision-makers act in four different ways:

1.They enable making sense of the situation in which they are.

2.They allow the simulation of the alternative representations of the future consequences of actions.

3.They allow individuals to establish communication to receive support in the social context with respect to their actions.

4.They allow committing to an action even in the face of a risk of loss.

Tuckett and Nikolic (2017) indicated that a fundamental feature of the CNT is that emotional processes play an inseparable role rather than a peripheral role, and compared CNT and rational decision-making. To explain this comparison on Figure

Conviction Narratives are formed in interaction with other financial actors. Conviction narratives such as the idea that the narratives in organisations are created through the contributions of employees of all levels are formed with the involvement of all market actors. Shiller (2017) said that narratives are “viral,” that they emerge randomly just like organisms in evolutionary biology and are contagious, and that mutated narratives will bring forth unpredictable changes in the economy. These findings prove quite apt for today’s world considering that numerous social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter are used actively by millions of users today. In such social channels, stories on financial products or markets are created collectively, and influence masses. Therefore, including narratives in economic models would help creating more robust models with greater explanatory power in both explaining periods of crisis and assessing the value of financial assets.

Crises, Asset Price Bubbles, and Narratives

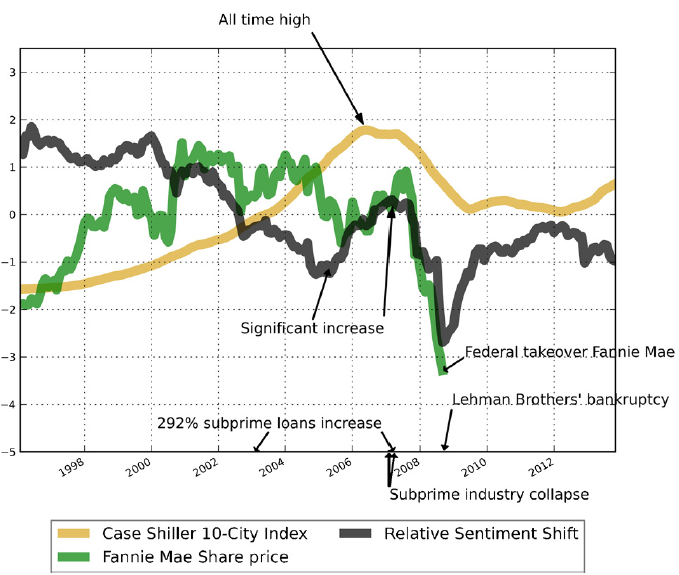

The concept of crisis has been expressed in the literature of economy with various terms such as depression; within the framework of the theory of asymmetric information, Mishkin (1996, as cited in Delice 2003) defines financial crises as follows: “A financial crisis is a non-linear degradation occurring in financial markets as a result of the problems of adverse selection and moral hazard reaching advanced levels, and funds losing their effectiveness in being channeled to economic units presenting the most efficient investment opportunities.” An asset price bubble can be defined as a rapid rise in asset prices followed by a sudden drop. Kindleberger and Aliber (2005) defines an asset balloon as “a burst following a 15-40-month upward price movement”. Financial markets relive periods during which balloons occurred over and over again (the tulip balloon, the south sea balloon, the .com balloon, etc.) The conventional finance approach is incapable of explaining the emergence and subsequent burst of asset price balloons coherently. For, according to the conventional approach, individuals act rationally, and Adam Smith’s famous “Invisible Hand” is always at work. In the case of an imbalance in the market, an invisible hand intervenes and brings the markets to the optimal level (as cited in Bellotti, Taffler, & Tian, 2010). Emotional finance sets out from concepts such as unconscious mental processes, group feel and narratives to explain the emergence of asset price balloons. According to Tuckett and Taffler (2008), asset price balloons generally emerge along with new developments, especially when potentially exceptional returns are involved. According to emotional finance, there is a narrative that dominates the market during each bubble period. For instance, during the “.com” bubble, Tuckket and Taffler (2008) indicated that this was a “new economy” story, and that the dominant belief was that the internet would cause an unprecedented increase in yield in the US economy and in other economies. Similarly, according to Taffler and Eshraghi (2012), during the 2008 crisis hedge funds and fund managers became symbols of the “richest” and the “best,” and a story was created by the market that depicted “star” hedge fund managers in an exaggerated and unrealistic manner, as investment gods or gurus. Bellotti et al. (2010) claim that, during the balloon that emerged in the Stock Exchange of China between 2005-2007, the radical reform initiated by the Chinese government with respect to the markets, the successive large-scale public offers, and the increases that occurred in the index created among investors the story that this time the market was “definitely different.” Emotional finance not only demonstrates the asset price bubbles and the narratives that are dominant during periods of crisis, but also offers a methodology for an analysis of these narratives. Tuckett et al. (2014) developed the “relative sentiment shift” analysis to demonstrate how narratives affect markets. This analysis is different from sentiment analysis. It attempts at demonstrating shifts that occur in sentiments in time rather than categorising the sentiments of an instrument or a set of instruments in an absolute manner. Analysing the sentiment shift occurring in narratives dominating the market during asset price balloon or crisis periods helps explaining the emergence and burst of balloons and crises. Tuckett et al. (2014) analysed the media coverage published between 1996 and 2013 on Fannie Mae, one of the largest housing finance companies in the US, which went bankrupt following the crisis of 2008. The “relative sentiment shift” analysis was applied to the news obtained from the Reuters database for the time window in question, and the results were compared to the Case-Shiller Price index, the main indicator of the housing market. (See Figure

Examining Figure

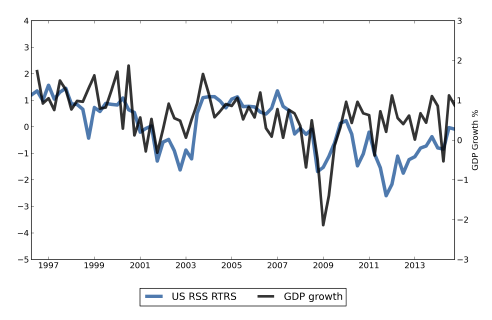

Examining the figure, a correlation between the two series can be observed. Granger causality tests and multivariate regression analyses were performed to determine whether the relative sentiment shift series could be used in forecasting GDP growth. As a result, it was demonstrated that the relative sentiment shift series could be used in forecasting GDP. In the emotional finance approach, narratives play a key role in understanding asset price bubbles and financial crises. According to Tuckett et al. (2014), narratives dissipate and increasingly and gradually eliminate doubt. And it is this phenomenon that produces asset price bubbles and similar mass phenomena.

Conclusion and Discussions

The idea that emotions are an important driving force of economy has a long history in economic literature, and actually dates back to Keynes. The theories developed by conventional finance up to the 1970s ignored this fact, and individuals were regarded as unemotional beings paying no regard to social benefits or moral outcomes. On the other hand, the conventional approach is risk-based, but what dominates the markets is uncertainty, which fact was ignored. This could prove a very important negligence. According to Tuckket and Nikolic (2017), the failure to include radical uncertainty in economic and financial models was among the main reasons of the crisis of 2008.

Emotional finance suggests an innovative approach to understand the phenomenon of investment and market movements through the concepts of group feel, states of mind, and phantasy. This study has attempted to examine narratives, which constitute one of the four building blocks of emotional finance. Narratives play a critical role in enabling individuals who must make decisions under uncertainty to imagine the future and to act. Also, the fact that narratives spread rapidly across social networks, virtually taking masses captive, is recognised as one of the fundamental explanations of the emergence of asset price balloons and financial crises.

It is believed that the increasing interest in understanding the emotions of market participants on assets and markets following the crisis of 2008 will accelerate studies on emotional finance. However, this may also cause the literature on emotional finance to be qualified as “crisis literature” or “asset price balloon literature” as was the case when Fama marginalised behavioural finance as “anomaly literature.” In this framework, studies observing the narratives created by market participants on unstructured data sources (newspaper articles, social media data, etc.) and using shifts in emotions as precursors may eliminate the criticism of “crisis literature” that may be levelled against emotional finance.

References

- Aven, T. (2007). A unified framework for risk and vulnerability analysis and management covering both safety and security. Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 92, 745–54.

- Aven, T., & Renn, O. (2009). On risk defined as an event where the outcome is uncertain. Journal of Risk Research, 12(1), 1-11.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Newman, L. S. (1994). How Stories Make Sense of Personal Experiences: Motives that Shape Autobiographical Narratives. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(6), 676–690.

- Bellotti, X. A., Taffler, R., & Tian, L. (2010). Understanding the Chinese Stock Market Bubble: The Role of Emotion. SSRN Electronic Journal. DOI:

- Bruner, J. (1991). The Narrative Construction of Reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21.

- Cabinet Office. (2002). Risk: Improving government’s capability to handle risk and uncertainty. Strategy Unit report. London: Strategy Unit.

- Campbell, S. (2005). Determining overall risk. Journal of Risk Research, 8, 569–81.

- Chong, K. & Tuckett, D. (2015). Constructing conviction through action and narrative: how money managers manage uncertainty and the consequence for financial market functioning. Socio-Economic Review, 13(2), 309-330.

- Delice, G. (2003). Finansal krizler: Teorik ve tarihsel bir perspektif [Financial Crises: A Theoretical and Historical Perspective]. Erciyes University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences Journal, 20, 57-81.

- Dervişcemaloğlu, B. (2016). Anlatıbilime Giriş [Introduction to Narrotology]. İstanbul: Dergah Publications.

- Engin, E. (2013). Fisher’ın Anlatı Paradigması Bağlamında Kurum Hikayeleri Üzerinden Kurumsal Değerlerin Anlamlandırılması: Bir Anlatı Analizi [Sensemaking of corporate values through corporate stories within the framework of Fisher's narrative paradigm: A narrative analysis] (Ph. D. Thesis). Marmara University Institute of Social Sciences, Department Of Public Relations.

- Eshraghi, A., & Taffler, R. (2015). Heroes and victims: Fund manager sensemaking, self-legitimation and storytelling. Accounting and Business Research, 45 (6-7), 691-714.

- Fludernik, M. (2009). An Introduction to Narratology. London: Routledge.

- Gabriel, Y. (2000). Storytelling in Organizations: Facts, Fictions, and Fantasies. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Graham, J. D., & Weiner, J. B. (1995). Risk versus risk: Tradeoffs in protecting health and the environment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Humphreys, M., & Brown, A.D. (2002). Narratives of organizational identity and identification: A case study of hegemony and resistance. Organization Studies, 23(3), 421–447.

- IRGC. (2005). White paper on risk governance. Towards an integrative approach. Geneva: IRGC.

- ISO. (2002). Risk management vocabulary. ISO/IEC Guide 73. Geneva: ISO.

- Johnson, S., & Tuckett, D. (2017). Narrative decision-making in investment choices: How investors use news about company performance. SSRN Electronic Journal. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.169593210.2139/ssrn.3037463

- Knight, F. H., (1921). Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Kindleberger, C., & Aliber, R. (2011). Manias, Panics, and Crises: A History of Financial Crises. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lowrance, W. (1976). Of acceptable risk – science and the determination of safety. Los Altos. CA: William Kaufmann Inc.

- McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories, Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100-122.

- McAdams, D. P., & McLean, K. C. (2013). Narrative identity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 233–238.

- Mitroff, I. I., &. Kilmann, R. H. (1975). Stories managers tell: A new tool for organizational problem solving. Management Review, 67 (7), 18–28.

- Nyman, R. (2015). An Algorithmic Investigation of Conviction Narrative Theory: Applications in Business, Finance and Economics (Ph. D. Thesis). University College London, The Department of Computer Science.

- Ochs, E., & Capps, L. (1996). Narrating the self. Annual Review of Anthropology, 25, 9-43.

- Sezen, İ. T. (2011). Dijital İnteraktif Ortamlarda Anlatının Yeri ve İnşası (Narrative in digital interactive media) (Ph. D. Thesis). Istanbul University, Institute Of Social Sciences, Radio and Television Cinema Department.

- Shiller, R. J. (2017). Narrative Economics. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2896857

- Statman, M. (2014). Behavioral finance: Finance with normal people. Borsa Istanbul Review, 14(2), 65-73.

- Taffler, R. (2017). Emotional finance: Investment and the unconscious. The European Journal of Finance, 24(7-8), 630-653.

- Taffler, R., & Tuckett, D. (2010). Emotional finance: The role of the unconscious in financial decisions. Behavioral Finance, 95-112.

- Türk Dil Kurumu (Turkish Language Association). (2018, November). Retrieved from http://www.tdk.gov.tr/index.php?option=com_gts&arama=gts&kelime=hik%C3%A2ye&uid=22916&guid=TDK.GTS.5be9c1ac320fe4.54203763

- Türk Dil Kurumu (Turkish Language Association). (2018, November). Retrieved from http://www.tdk.gov.tr/index.php?option=com_gts&arama=gts&guid=TDK.GTS.5be9c1d7859ca7.86047629

- Tuckett, D. (2011). Minding the Markets an Emotional Finance View of Financial Instability. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tuckett, D. (2012). Financial markets are markets in stories: Some possible advantages of using interviews to supplement existing economic data sources. Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control, 36, 1077 -1087.

- Tuckett, D., & Taffler, R. (2008). Phantastic objects and the financial market’s sense of reality: A psychoanalytic contribution to the understanding of stock market instability. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 89(2), 389-412.

- Tuckett, D., & Taffler, R. (2012). Fund Management: An Emotional Finance Perspective. CFA Institute.

- Tuckett, D., & Nikolic, M. (2017). The role of conviction and narrative in decision-making under radical uncertainty. Theory & Psychology, 27(4), 501–523.

- Tuckett, D., Smith, R. E., & Nyman, R. (2014). Tracking phantastic objects: a computer algorithmic investigation of narrative evolution in unstructured data sources. Social Networks, 38, 121–133.

- Willis, H. H. (2007). Guiding resource allocations based on terrorism risk. Risk Analysis, 27, 597–606.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 October 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-070-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

71

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-460

Subjects

Business, innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Dumanlı, A. N., & Aren*, S. (2019). Role of Narratives in Financial Decision Making from Perspective of Emotional Finance. In M. Özşahin (Ed.), Strategic Management in an International Environment: The New Challenges for International Business and Logistics in the Age of Industry 4.0, vol 71. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 416-428). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.10.02.38